Impact of treatment with GLP-1RAs on suicide attempts in adults persons with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective comparative effectiveness study based on a global TriNetX health research database

Abstract

Objective

To assess the association between glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) treatment and the risk of suicide attempts in people with type 2 diabetes (T2D), with a focus on subgroups with and without a history of depression or suicide attempts.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study utilized TriNetX, a federated network of real-world data. Using the Global Collaborative Network data, we collected electronic medical records from 113 health care organizations with 135 million patient records with 8 million with T2D, 83% from the United States. The four cohorts were identified based on age, medication, diagnosis, and presence of depression or suicide attempts. Analytic methods included measures of association and number of Instances, with propensity score matching employed to mitigate potential confounders. The primary outcome was the incidence of suicide attempts among people with T2D with GLP-1RA treatment in comparison with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4i) treatment.

Results

People with T2D treated with GLP-1RA consistently exhibited a lower risk of suicide attempts compared to those treated with DPP-4i. This was particularly significant in people with a history of depression or suicide attempts. The risk and odds ratios were significantly lower in the GLP-1RA-treated cohorts than in DPP-4i across all analyses.

Conclusion

As compared with DPP-4i, our analysis shows a protective effect associated with GLP-1RA treatment on the risk of suicide attempts among people with T2D. However, further research, particularly prospective and randomized studies, is necessary to confirm these observations and understand the underlying mechanisms.

1 INTRODUCTION

The advent of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) has marked a significant advancement in the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D), offering not just glycemic control but also benefits in weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction.1-3 However, the safety profile of these agents has come under scrutiny. Concerns have been heightened by reports of rare yet severe psychiatric adverse events, including suicide and self-injury, potentially linked to GLP-1RA treatments such as liraglutide and semaglutide, as indicated by warnings from health authorities like the Icelandic Medicines Agency.4, 5 An analysis of a subgroup within the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database showed a slight increase in the reporting odds ratio (ROR) for suicide and self-injury in children who were taking GLP-1RA (ROR: 2.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–6.13, p = .05).6 Randomized controlled trials of semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly for obesity excluded persons with severe depression, but approximately 15% of persons enrolled in these studies were treated with antidepressants without evidence of a greater likelihood of adverse outcomes.1 Randomized controlled trials of liraglutide 3.0 mg daily for obesity similarly did not show an increase in the likelihood of depression or suicidality.1 The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is currently investigating the potential correlation between GLP-1RA and the increased likelihood of experiencing suicidal thoughts and engaging in self-harming behaviors.5 Also, the FDA is currently assessing the necessity of regulatory measures following the receipt of reports in its FDA FAERS regarding alopecia (hair loss), aspiration, and suicidal ideation among individuals using GLP-1RA.7 It is noteworthy that concerns have been raised pertaining to the potential adverse psychiatric effects of bariatric surgery. Some studies have shown increased depression and suicide risk.1-3 Although other studies suggest the opposite may occur,1 with there being a potential for overall improvement in depression, a subset of persons show worsening, leading to suicidal behavior after these procedures.2 As yet, there is no firm conclusion on this issue. It is therefore important to determine whether real-world evidence does or does not suggest that GLP-1RA treatment of people with diabetes is associated with a greater risk of suicide.

2 METHODS

In this retrospective cohort study, data were sourced from the TriNetX Global Collaborative Network data, encompassing electronic medical records from 113 health care organizations with 135 million patient records. The database contains around 8 million individuals diagnosed with T2D, with over 83% residing in locations inside the United States. TriNetX is a global health research network that revolutionizes drug discovery and development by linking pharmaceutical companies, study sites, investigators, and people through a shared real-world data platform (http://www.trinetx.com). It facilitates clinical and observational research by providing real-time access to longitudinal clinical data and advanced analytics to enhance protocol design, site selection, and patient recruitment. Ensuring data privacy and compliance, TriNetX adheres to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and General Data Protection Regulation.

The overarching aim was to examine the impact of GLP-1RA on suicide attempts among people diagnosed with T2D, specifically examining those with concurrent diagnoses of depression or suicide attempts to ascertain whether there was an adverse effect of GLP-1RA.

This study exclusively involved individuals aged 18 and older diagnosed with T2D. Our analysis was segmented into two distinct parts, comprising four cohorts, differentiated based on the use of GLP-1RA compared to dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) and the assessed risk level. DPP-4i was selected as a comparable group because both are incretin-based therapies. High-risk individuals were identified as those with a history of suicide attempts, antidepressant medication use, or diagnoses of mood disorders such as dysthymic disorder or major depressive disorder, or those who had received treatments with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors 5 years before the index event, which is starting either GLP-1RA or DPP-4i.

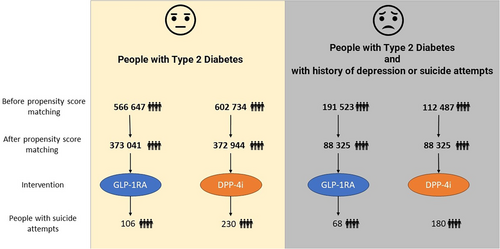

- Cohort 1 and 2: The first analysis evaluated the risk of suicide attempts in all people with T2D, comparing those treated with GLP-1RA (Cohort 1, 566 645 people) against those treated with DPP-4i (Cohort 2, 602 734 people).

- Cohort 3 and 4: The second analysis targeted high-risk people, with Cohort 3 comprising 191 523 people with T2D on GLP-1RA treatment and Cohort 4 comprising 112 487 people with T2D on DPP-4i treatment.

The analytical procedure involved two main steps: first, establishing the cohorts by selecting individuals who were at least 18 years old, had a history of T2D and were taking GLP-1RA for GLP-1RA cohorts and DPP-4i for DPP-4i for DPP-4i cohorts second, excluding individuals with age <18 years and who were taking DPP-4i treatment in GLP-RA cohorts and GLP-1RA treatment in DPP-4i cohorts. In order to guarantee precision and pertinence during the analysis, it was necessary to establish explicit definitions for the index event, outcome criteria, and time frame.

The index event for each cohort, which serves as the starting point for the analysis, is defined by the initial date of GLP-1RA or DPP-4i treatment. Observations of outcomes began a day after the first occurrence of the index event and continued for 5 years after the index event. A total of 177 people from Cohort 1 and 274 people from Cohort 2 were excluded because they had a suicide attempt more than 5 years before the index event.

To gauge the relative frequency of suicide events with GLP-1RA vs DPP-4i, the risk difference per 100 000 persons and the ORs were calculated, both with 95% CIs. To mitigate potential confounders and biases, propensity score matching was employed based on patient characteristics like age, race, gender, depression-related diagnosis, and use of antidepressant medications to create comparable groups for a balanced comparison. Outcomes were meticulously defined using a range of diagnostic and medication codes, focusing particularly on suicide attempts and the use of GLP-1RA or DPP-4i.

Ethical considerations were paramount, with all data handling and analyses conducted in compliance with relevant standards and regulations. Despite the study's retrospective nature and the use of deidentified data negating the need for specific patient consent, an appropriate ethics committee rigorously reviewed and approved the study's design and methods. This ensured adherence to ethical research principles and alignment with guidelines for secondary data analysis, reflecting the study's commitment to upholding ethical standards while contributing valuable insights into the treatment and management of T2D.

3 RESULTS

In the present study, we conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis of patient characteristics across different cohorts of people with T2D receiving GLP-RA and DPP-4i. The cohorts were divided based on their treatment regimens and depression risk characteristics.

Initially, Cohort 1 (T2D with GLP-RA) and Cohort 2 (T2D with DPP-4i) comprised 566 647 and 602 734 people, respectively. After propensity score matching, both cohorts were balanced with 373 218 people each, allowing for a more accurate comparison of demographic variables such as age, race, and gender. The same process was applied to Cohorts 3 and 4 (groups at high-risk of suicide), which comprised 191 523 and 112 487 people, respectively. After propensity score matching, both cohorts were balanced with 88 325 people each.

Table 1 presents the results of the patient count and demographic characteristics before and after propensity score matching, showing that the procedure resulted in groups equivalent in age, sex, ethnicity, and depression-related diagnoses. As compared with DPP-4i, The GLP-1RA cohort demonstrated fewer suicide attempts at baseline. As described under “Methods, “177 people were excluded from those taking GLP-1RA, and 274 were excluded from those taking DPP-4i because they had a suicide attempt more than 5 years before starting the medication. These differences were statistically significant (chi-square = 20.9004, p = <.00001).

| Cohort 1 and cohort 2 patient count before and after propensity score matching | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient count before matching | Patient count after matching | ||||||||||

| Cohort | 1 - T2D w GLP-RA | 566 647 | 373 218 | ||||||||

| 2 - T2D w DPP-4i | 602 734 | 373 218 | |||||||||

| Before Matching | After Matching | ||||||||||

| Cohort | Demographics | Mean ± SD | People | % of cohort | p value | Std diff. | Mean ± SD | People | % of Cohort | p-Value | Std diff. |

| 1 | Current Age | 60.1 ± 13.1 | 566 645 | 100% | <.0001 | 0.8264 | 65.1 ± 11.1 | 373 218 | 100% | <0.0001 | 0.0198 |

| 2 | 70.8 ± 12.8 | 602 734 | 100% | 64.8 ± 11.5 | 373 218 | 100% | |||||

| 1 | White | 367 065 | 64.78% | <.0001 | 0.2172 | 226 858 | 60.78% | <0.0001 | 0.0112 | ||

| 2 | 326 554 | 54.18% | 224 807 | 60.24% | |||||||

| 1 | Female | 347 005 | 61.24% | <.0001 | 0.1806 | 219 802 | 58.89% | <0.0001 | 0.0109 | ||

| 2 | 315 401 | 52.33% | 217 799 | 58.36% | |||||||

| 1 | Not Hispanic or Latino | 305 547 | 53.92% | <.0001 | 0.1379 | 183 688 | 49.22% | <0.0001 | 0.0549 | ||

| 2 | 283 561 | 47.05% | 173 455 | 46.48% | |||||||

| 1 | Hispanic or Latino | 106 559 | 18.81% | <.0001 | 0.1323 | 62 793 | 16.83% | 0.0061 | 0.0063 | ||

| 2 | 83 911 | 13.92% | 61 910 | 16.59% | |||||||

| 1 | Black or African American | 49 640 | 8.76% | <.0001 | 0.0189 | 32 696 | 8.76% | <0.0001 | 0.021 | ||

| 2 | 49 621 | 8.23% | 34 945 | 9.36% | |||||||

| 1 | Asian | 15 168 | 2.68% | <.0001 | 0.1424 | 12 559 | 3.37% | 0.0004 | 0.0082 | ||

| 2 | 33 068 | 5.49% | 13 118 | 3.52% | |||||||

| 1 | Mood [affective] disorders | 116 267 | 20.52% | <.0001 | 0.2862 | 53 855 | 14.43% | <0.0001 | 0.0189 | ||

| 2 | 62 029 | 10.29% | 51 399 | 13.77% | |||||||

| 1 | Depressive episode | 95 424 | 16.84% | <.0001 | 0.2539 | 44 168 | 11.83% | <0.0001 | 0.0171 | ||

| 2 | 51 035 | 8.47% | 42 124 | 11.29% | |||||||

| 1 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent | 29 822 | 5.26% | <.0001 | 0.1996 | 10 427 | 2.79% | <0.0001 | 0.0177 | ||

| 2 | 9870 | 1.64% | 9364 | 2.51% | |||||||

| 1 | Bipolar disorder | 13 418 | 2.37% | <.0001 | 0.0901 | 6530 | 1.75% | 0.0655 | 0.0043 | ||

| 2 | 7109 | 1.18% | 6323 | 1.69% | |||||||

| 1 | Persistent mood [affective] disorders | 8547 | 1.51% | <.0001 | 0.0527 | 4485 | 1.20% | 0.0372 | 0.0048 | ||

| 2 | 5607 | 0.93% | 4291 | 1.15% | |||||||

| 1 | Unspecified mood [affective] disorder | 8266 | 1.46% | <.0001 | 0.0865 | 3496 | 0.94% | <0.0001 | 0.0105 | ||

| 2 | 3548 | 0.59% | 3130 | 0.84% | |||||||

| 1 | Manic episode | 474 | 0.08% | .227 | 0.0022 | 315 | 0.08% | 0.2051 | 0.0029 | ||

| 2 | 466 | 0.08% | 284 | 0.08% | |||||||

| Cohort 3 and cohort 4 patient count before and after propensity score matching | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient count before matching | Patient count after matching | ||||||||||

| Cohort | 5- T2D w GLP-1RA (focus on high-risk group) | 191 523 | 88 325 | ||||||||

| 6- T2D w DPP-4i (focus on high-risk group) | 112 487 | 88 325 | |||||||||

| Before matching | After Matching | ||||||||||

| Demographics | Mean ± SD | People | % of cohort | p value | Std diff. | Mean ± SD | People | % of Cohort | p-Value | Std diff. | |

| 3 | Current Age | 59.1 ± 12.8 | 191 523 | 100% | <.0001 | 0.829 | 65.7 ± 11.3 | 88 325 | 100% | 0.0002 | 0.0175 |

| 4 | 69.8 ± 12.9 | 112 487 | 100% | 65.9 ± 11.6 | 88 325 | 100% | |||||

| 3 | Not Hispanic or Latino | 132 456 | 69.16% | <.0001 | 0.0965 | 58 467 | 66.20% | 0.0543 | 0.0092 | ||

| 4 | 72 693 | 64.62% | 58 849 | 66.63% | |||||||

| 3 | White | 124 916 | 65.22% | <.0001 | 0.0556 | 56 683 | 64.18% | 0.0295 | 0.0104 | ||

| 4 | 70 366 | 62.56% | 57 121 | 64.67% | |||||||

| 3 | Female | 122 639 | 64.03% | <.0001 | 0.1339 | 50 205 | 56.84% | < 0.0001 | 0.0386 | ||

| 4 | 64 692 | 57.51% | 51 887 | 58.75% | |||||||

| 3 | Black or African American | 33 233 | 17.35% | <.0001 | 0.0784 | 13 725 | 15.54% | 0.2682 | 0.0053 | ||

| 4 | 16 295 | 14.49% | 13 894 | 15.73% | |||||||

| 3 | Hispanic or Latino | 15 015 | 7.84% | <.0001 | 0.0423 | 8295 | 9.39% | < 0.0001 | 0.0234 | ||

| 4 | 10 140 | 9.01% | 7702 | 8.72% | |||||||

| 3 | Asian | 2694 | 1.41% | <.0001 | 0.1409 | 1854 | 2.10% | 0.0013 | 0.0153 | ||

| 4 | 4053 | 3.60% | 1665 | 1.89% | |||||||

| 3 | Mood [affective] disorders | 97 800 | 51.06% | <.0001 | 0.1885 | 39 005 | 44.16% | 0.0035 | 0.0139 | ||

| 4 | 46 915 | 41.71% | 39 615 | 44.85% | |||||||

| 3 | Depressive episode | 79 844 | 41.69% | <.0001 | 0.1584 | 31 862 | 36.07% | 0.0115 | 0.012 | ||

| 4 | 38 281 | 34.03% | 32 373 | 36.65% | |||||||

| 3 | Major depressive disorder, recurrent | 29 822 | 15.57% | <.0001 | 0.209 | 9010 | 10.20% | 0.0337 | 0.0101 | ||

| 4 | 9870 | 8.77% | 9282 | 10.51% | |||||||

| 3 | Bipolar disorder | 10 434 | 5.45% | <.0001 | 0.0546 | 4348 | 4.92% | 0.4396 | 0.0037 | ||

| 4 | 4809 | 4.28% | 4278 | 4.84% | |||||||

| 3 | Persistent mood [affective] disorders | 8487 | 4.43% | <.0001 | 0.0243 | 4081 | 4.62% | 0.2743 | 0.0052 | ||

| 4 | 5562 | 4.95% | 4178 | 4.73% | |||||||

| 3 | Unspecified mood [affective] disorder | 7308 | 3.82% | <.0001 | 0.0727 | 2408 | 2.73% | 0.0277 | 0.0105 | ||

| 4 | 2858 | 2.54% | 2561 | 2.90% | |||||||

| 3 | Manic episode | 373 | 0.20% | .0016 | 0.0117 | 171 | 0.19% | 0.0792 | 0.0084 | ||

| 4 | 281 | 0.25% | 205 | 0.23% | |||||||

- Abbreviations: %, percentage; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-RA1, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; N, Total number of people in a cohort; Std diff., standardized difference; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

3.1 Cohort 1 and 2 Analysis: Suicide Attempts in all People with T2D with GLP-1RA vs those on DPP-4i Treatment

In the first analysis, we assessed the risk of suicide attempts among people with T2D treated with GLP-1RA and those treated with DPP-4i. Cohort 1 (T2D with GLP-1RA) consisted of 373 041 people, among whom 106 had a suicide attempt, resulting in a risk of 28.41 per 100 000. In comparison, Cohort 2 (T2D with DPP-4i) included 372 944 people, with 230 experiencing a suicide attempt, for a risk of 61.67 per 100 000. The risk difference between the two cohorts was significant at −33 (95% CI: −43, −24) per 100 000 with an OR for those with GLP-1RA vs DPP-4i treatment of 0.461 (95% CI: 0.366, 0.58), p < .001 (Table 2).

| Comparison | Cohort | Sample size (n) | People with outcome | Risk per 100 000 | Risk difference (95% CI) per 100 000 | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2D with GLP1-RA vs T2D with DPP-4i | 1: T2D w GLP-1RA | 373 041 | 106 | 28.41 | −33 (−43, −24) | <.001 | 0.461 (0.366, 0.58) |

| 2: T2D with DPP-4i | 372 944 | 230 | 61.67 | ||||

| T2D with GLP1-RA vs T2D with DPP-4i (including only people with a history of depression or suicide attempts) | 3: T2D with GLP-1RA | 88 325 | 68 | 76.98 | −127 (−162, −92) | <.001 | 0.377 (0.285, 0.499) |

| 4: T2D with DPP-4i | 88 325 | 180 | 203.79 |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; n, sample size; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

3.2 Cohort 3 and 4 Analysis: Suicide Attempts in People with T2D with GLP-1RA Treatment vs DPP-4i (including only people with high-risk depression/suicide risk)

This analysis focused on people identified as high-risk risk (with a history of depression or suicide attempts). Cohort 3 (T2D with GLP-1RA) included 88 325 people, with 68 suicide attempts, equating to a risk of 76.98 per 100 000, and Cohort 4 (T2D with DPP-4i) consisted of 88 623 people, with 176 suicide attempts, presenting a higher risk of 203.79 per 100 000. The risk difference was −127 (95% CI: −162, −92) per 100 000 with a p value of <.001. The OR for those with GLP-1RA vs DPP-4i treatment was 0.377 (95% CI: 0.285, 0.499) (Table 2).

4 DISCUSSION

In this population-based study involving a large number of participants with T2D, those treated with GLP-1RA exhibited a consistently lower risk of suicide attempts compared to those treated with a DPP-4i. The high-risk group of individuals with a history of depression or suicide attempts showed the same outcome. The risk ratios and ORs were significantly lower in the GLP-1RA treated cohorts across all analyses, strengthening the argument that there is no adverse effect of GLP-1RA treatment in increasing suicide attempts among the diabetic population.

The relationship between GLP-1RAs and mental health is complex. Studies have reported a range of experiences from people using GLP-1RAs, including both positive effects on mood and negative experiences such as heightened anxiety and difficulty sleeping.8 Real-world pharmacovigilance analysis has not shown a disproportionate increase in suicide/self-injury events overall associated with GLP-1RAs, but nuances exist, with a reported increase in children (OR: 2.50, 95%CI 1.02–6.13, p = .05).6 Moreover, post hoc pooled data analysis from randomized controlled trials of liraglutide, a GLP-1RA, showed similarly low rates of depression and anxiety between the liraglutide and placebo groups but did reveal a small numerical imbalance in suicidal ideation among liraglutide users.4 Based on information from the Icelandic Medicines Agency, the EMA is conducting a thorough examination that will study approximately 150 cases.5 There is some evidence that GLP-1RA can penetrate the blood–brain barrier,9 and GLP-1 receptors are present in the central nervous system,10 which may affect hunger signals and elevate neuropsychiatric risks5 or which, alternatively, may have psychiatric as well as metabolic benefits. After the submission of the present manuscript, Wang and coworkers published a similar analysis using the TriNetX database, showing that, compared with a propensity score matched group of 27,276 persons with diabetes taking all other diabetes medications, among the same number of persons taking GLP-1RA for diabetes the likelihood of suicidal ideation was >60% lower, with similar findings among persons with obesity not having diabetes taking vs. not taking GLP-1RA. The present study made the more specific comparison of GLP-1RA with DPP-4i, and compared the general population of persons with diabetes as well as those with prior history of depression or suicide attempts.11

The study's strengths lie in its large sample size and the use of a comprehensive global federated health research network, providing a robust dataset for examining the effects of GLP-1RA on suicide attempts in diabetic people. Its detailed stratification of people into specific cohorts based on their medical history allowed for a nuanced analysis of the treatment's impact across different subgroups, enhancing the relevance and specificity of the findings. Additionally, using propensity score matching to control for confounders adds to the credibility of the results.

However, this study has several limitations. Its retrospective nature inherently restricts the ability to establish causality and residual confounding factors may not be accounted for or measured. People with T2D initiating GLP-1RA may experience disparate care access compared to DPP-4i users. Our findings indicate a statistically significant higher incidence of suicide attempts in patients subsequently prescribed DPP-4i compared to GLP-1RA, suggesting potential selection bias despite propensity matching. The reliance on electronic medical records and diagnostic codes may lead to misclassification or underreporting of outcomes like suicide attempts. Access to GLP-1RA in the United States often has a high-cost barrier, whereas the DPP-4i have become much less expensive, a potential cause of selection bias. The study's setting within a specific network of health care organizations might limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Furthermore, although the data were adjusted for several known confounders, unknown or unmeasured variables could still influence the results. The study did not consider other factors that might be related to suicide, such as blood glucose control levels and episodes of hypoglycemia, family history of suicide, and socioeconomic status. Lastly, the observational design cannot match the rigor of randomized controlled trials in determining treatment efficacy and safety, making it crucial to approach the conclusions to understand these contextual limitations.

5 CONCLUSION

This retrospective cohort study showed no evidence of an adverse effect of GLP-1RA in increasing the risk of suicide attempts among people with T2D, especially those with a history of depression or suicide attempts. Analysis across various patient subgroups consistently showed that those treated with GLP-1RA had significantly lower risk and fewer instances of suicide attempts compared to those treated with DPP-4i. This study argues strongly against there being a potential for GLP-1RA to cause an increase in suicide risk. These findings require further investigation to more fully understand the underlying mechanisms and broader clinical implications.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

DISCLOSURE

Anoop Misra is the associate editor and Zachary Bloomgarden is editor-in-chief of the journal and also coauthors of this article. They were excluded from the peer-review process and all editorial decisions related to the acceptance and publication of this article. Peer-review was handled independently by another editor-in-chief and the assigned associate editor.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Patient consent was not applicable to this study as it did not involve human participants.