Metastatic Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma Presenting as an Incidental Posterior Mediastinal Mass

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is an uncommon neuroendocrine tumour that is usually asymptomatic at its onset and therefore may not present clinically until the patient has developed advanced or metastatic disease. Common metastatic sites include cervical lymph nodes, liver, bone and lung. This is the case of a patient who presented with an incidental posterior mediastinal mass. Because the posterior mediastinum is an unusual location for MTC, MTC was not a consideration and preliminary histopathological testing did not include calcitonin, which would have been diagnostic. This case highlights the importance of testing for calcitonin more regularly when encountering a mass of unknown origin with neuroendocrine morphology, which may lead to earlier detection of MTC and thus improved prognosis.

Abstract

A posterior mediastinal mass of unknown origin was eventually identified as metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma after thyroid FNA with calcitonin staining led to a review of the original histopathology and application of additional immunohistochemistry. This case highlights the importance of calcitonin testing for masses with neuroendocrine features, potentially enabling earlier detection of MTC.

1 Introduction

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), a neuroendocrine tumour (NET) of the parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland, is the third most common thyroid carcinoma, representing 4%–8% of thyroid malignancies in the United States [1, 2]. It is sporadic in 75%–80% of cases and hereditary in the other 20%–25%. MTC usually presents at age 30–50, as an asymptomatic, unifocal tumour with early lymph node involvement. In very rare instances of advanced metastasis, patients may experience intractable diarrhoea, flushing or Cushing's syndrome [3]. In approximately 70% of MTC cases, once the patient presents with a palpable thyroid nodule, the tumour will already have metastasised, usually to the cervical lymph nodes, less often to the liver, lungs or bones and very rarely to other sites [4, 5]. Prognosis is dependent upon age and stage at diagnosis but is generally poor, given its challenging diagnostic limitations and surgical resection as the main curative option [6, 7]. We searched the PubMed database using the keywords “medullary thyroid carcinoma or MTC” and “posterior mediastinum or posterior mediastinum metastasis.” To our knowledge, this is the first report of metastatic MTC presenting as a posterior mediastinal mass.

In this report, we describe a case of a patient with an incidental finding of a superior posterior mediastinal lesion that was initially thought to be a pulmonary carcinoid tumour, and with further workup, was diagnosed as metastatic MTC.

2 Case

A 63-year-old asymptomatic male, with no abnormal exam findings or significant medical history aside from 3- to 4-pack-year smoking, initially presented for coronary CT angiogram calcium scoring due to a family history of cardiac disease. He was incidentally found to have a 3.0 × 2.6 cm superior mediastinal lesion. He was sent for follow-up PET CT scan, which showed a hypermetabolic (SUV max 4.1) superior posterior mediastinal mass at the thoracic inlet with leftward tracheal deviation. No abnormal FDG avidity in the neck and no hilar or axillary lymphadenopathy were noted. At that time, the differential diagnosis included NETs such as schwannoma, low grade NET, benign adenopathy or less likely ectopic thyroid tissue or a complex cystic lesion.

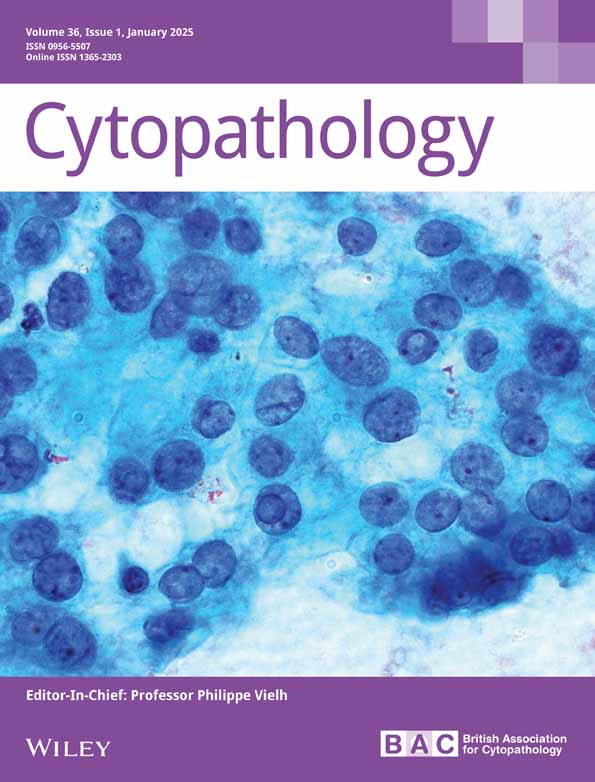

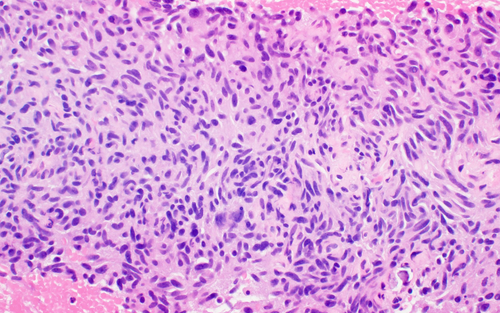

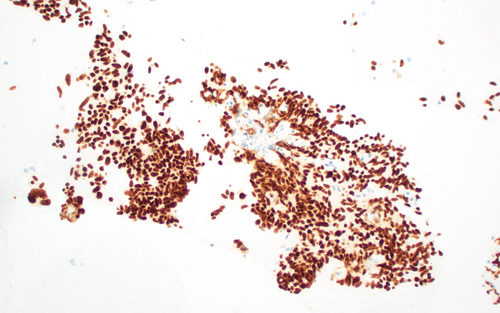

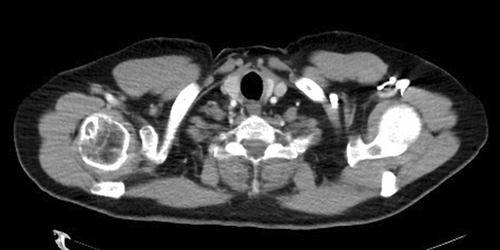

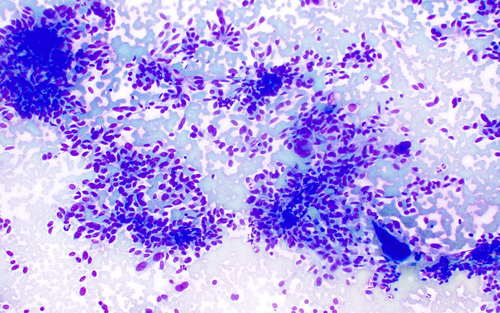

The patient followed up with a nuclear thyroid scan, which showed no uptake in the mediastinal mass, but did note decreased tracer activity focally in the right upper-mid thyroid pole possibly signifying a cold nodule. At that time, the lesion was thought to be a schwannoma originating in the vagus nerve. One month later, the patient underwent ultrasound-guided endoscopic biopsy of the mediastinal mass. Histopathology displayed elongated, uniform tumour cells with smooth nuclear contours forming loosely cohesive groups, lacking necrosis and mitotic figures (Figure 1) with strong positive immunostaining for chromogranin-A, TTF-1 (Figure 2), synaptophysin (Figure 3), CD56 and pancytokeratin. These findings were consistent with a low-grade NET. Given the very low Ki-67 proliferation index, the diagnosis was narrowed to a low-grade pulmonary carcinoid tumour.

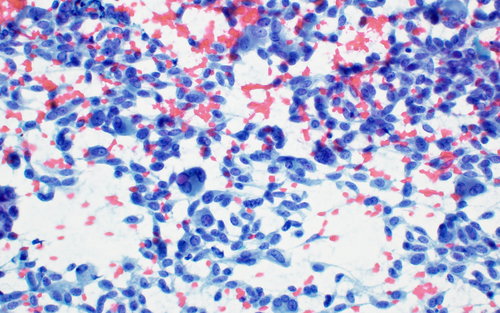

Before proceeding with surgical resection, the patient underwent dotatate scanning, which demonstrated an avid nodule corresponding to his known mediastinal mass (Figure 4) and another in the right thyroid (Figure 5). A right thyroid lobe nodule and two abnormal neck lymph nodes were detected on ultrasound. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the thyroid nodule was subsequently performed. Diff Quik and Papanicolaou-stained smear slides showed increased cellularity and lack of colloid, numerous elongated cells with eccentric nuclei, nuclear enlargement and some cells with multinucleation (Figures 6 and 7). Some cells were spindle shaped. Cells displayed stippled chromatin and granular cytoplasm. Due to the patient's recent diagnosis of carcinoid, the diagnostic considerations were now primary carcinoid with metastasis to the thyroid, versus primary MTC with metastasis to the mediastinum, or less likely, two different NETs. Immunohistochemistry was performed on the thyroid nodule FNA cytology cell block and revealed positivity for neuroendocrine markers (Synaptophysin, Chromogranin and CD56) as well as calcitonin and TTF1, establishing a diagnosis of primary MTC. Once the pathologist who had evaluated the endoscopic core biopsy from the original mediastinal mass was notified of the diagnostic considerations, a calcitonin stain on the initial core biopsy specimen was ordered, which revealed calcitonin immunopositivity. The patient's serum calcitonin levels were then examined and came back elevated at 2957 pg/ML. Free metanephrine was elevated at 85 pg/ML. The initial mediastinal mass biopsy diagnosis was amended and the diagnosis of MTC with metastases to the chest was confirmed.

The patient underwent a total thyroidectomy, central and bilateral neck dissection and mediastinal mass resection. Given his high risk for recurrence due to positive margins, surgery was followed by adjuvant radiation therapy for 7 weeks.

Pathology from the total thyroidectomy revealed a 1.5-cm pT1bN1b MTC in the right thyroid lobe with focal microscopic extrathyroidal extension, focally positive margins, lymphatic invasion and a 4-cm metastatic deposit in the mediastinum (previously biopsied), extra nodal extension and positive right lateral neck lymph nodes. Of note, testing on only a small sample by FISH showed that his MTC was RET-negative. Genetic testing (via hotspot) did not show any germline RET gene mutations and CARIS testing was RET negative as well but did show MEK1 positivity.

After the patient's surgery, MRI brain and abdomen showed no abdominal or intracranial metastases. PTH decreased from 99 to 40, CEA decreased from 57 to 4.4 and calcitonin decreased from approximately 2900 to less than 5.

3 Discussion

In our patient's case, there was a delay in diagnosis, given the rare initial presentation of a posterior mediastinal mass, for which the differential diagnosis is broad. NETs are often highest on the differential, as they account for 20% of all mediastinal tumours in adults, with 90%–95% of those occurring in the posterior mediastinum. This may be related to the location of peripheral nerves in the posterior mediastinum. Other considerations, especially when the mass involves the spinal canal, includes meningoceles, abnormal neuro-intestinal development, malignant lymphomas, myelolipomas and extramedullary haematopoiesis [8]. Although posterior mediastinal NETs do occasionally cause compressive or neurologic symptoms, they are typically asymptomatic and therefore patients with posterior mediastinal NETs often have delayed diagnosis. However, they are also less likely to be malignant than anterior and middle mediastinal tumours with 70%–80% of them turning out benign [9].

Although MTC is of neuroendocrine origin, it does not typically metastasise to the posterior mediastinum. Moreover, there is an overlap in the immunohistochemical markers of NETs. Therefore, it is reasonable that the index of suspicion for MTC in our patient's mass was low and that it was initially mistaken for another NET. Typical NETs express chromogranin A, synaptophysin and TTF1 [10]. MTC may express synaptophysin, chromogranin A and TTF1 as well as calcitonin. Additional immunostains that have been expressed in MTCs include somatostatin, GRP and VIP and rarely, serotonin, prostaglandin or ACTH [7].

As in our patient's case, when rendering a first-time diagnosis of a NET of unknown origin, it is important to use a multimodal approach including thyroid ultrasound, FNA and serum calcitonin, which is the most sensitive marker for detecting MTC. It is also helpful to associate calcitonin levels with CEA levels and to utilise calcitonin and CEA doubling time for prognostic purposes [7, 11]. In addition, calcitonin immunostaining should be performed as a confirmatory immunohistochemical marker, even if the mass's location is unusual for metastatic MTC. This could lead to earlier detection of MTC if present and consequently, improve prognosis.

Author Contributions

C.G.: Conceptualization, investigation, data curation, project administration, writing – original draft, review and editing. D.D.: Data curation, writing – review and editing. T.B.: Conceptualization, data curation, writing – review and editing, supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.