Factors beyond diagnosis and treatment that are associated with return to work in Australian cancer survivors—A systematic review

Abstract

Return to work (RTW) is a marker of functional recovery for working-age cancer survivors. Identifying factors that impact on RTW in cancer survivors is an essential step to guide further research and interventions to support RTW. This systematic review aimed to identify nontreatment, non-cancer-related variables impacting RTW in Australian cancer survivors. A systematic search was conducted in EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PubMed, and Google Scholar. Studies were eligible if they included: (1) adults living post diagnosis of malignancy; (2) quantitative data for nontreatment, non-cancer-related variables impacting RTW; (3) only Australian participants. Included studies were critically appraised, and relevant data extracted and synthesized narratively. Six studies were included in the review, published between 2008 and 2020. Studies were of variable quality and mixed methodologies. One study included malignancies of any type with the remainder focusing on survivors of colorectal cancer (n = 3), oropharyngeal cancer (n = 1), and glioblastoma multiforme (n = 1). Multiple factors were related to RTW in individual studies, including older age, presence of three or more comorbidities, fewer work hours pre-morbidly, lower body mass index, longer than recommended sleep duration, and not having private health insurance; however, there was limited consistency in findings between studies. Other variables examined included: occupation type, household income, healthy lifestyle behaviors, flexibility, and duration of employment with workplace; however, no significant associations with RTW were reported. Further research is required to gather compelling evidence on factors that influence RTW in Australian cancer survivors.

1 INTRODUCTION

An ageing population, improved cancer detection, and enhanced treatments are contributing to a growing number of cancer survivors.1 The 5-year relative survival for all cancers combined was 69.7% in Australia between 2013 and 2017, an increase from 51.3% 25 years earlier.2 A substantial number of cancer survivors in Australia are of working age; specifically, 54,382 Australians of working age (aged between 25 and 64 years) were diagnosed with cancer in 2017, representing 39% of all cancers in that year.2 In the 2013 to 2017 period, the 5-year relative survival for all cancers combined for Australians aged 25–64 years ranged between 76% and 91%.2

The burden of cancer can cause widespread disruption to daily routine and detrimentally impact autonomy.3, 4 Side effects can cause physical and psychological challenges to work participation, with survivors having a significantly higher risk of unemployment, reduced work hours or early retirement.3, 5 Disruption to work during cancer treatment is known to adversely affect the financial wellbeing of patients and their families.6-9 Furthermore, work disruption negatively affects quality of life and is linked to higher rates of anxiety and depression.10 Despite Australia having universal health care and social welfare benefits, the financial consequences to the individual, their families, and society from lack of reintegration into the workforce remain a significant problem.8, 11 An analysis of a 2015 cross-sectional survey conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics indicated that 46% of working-aged cancer survivors were not in active work, resulting in $1.7B of lost productivity, and those without tertiary qualifications were almost four times more likely not to be employed.11

For many survivors, reestablishing normalcy to their lives is a key goal.12 A recurring theme throughout the survivorship literature is that large numbers of working-age cancer survivors are both willing and able to return to work (RTW) with very little impact to their performance. Internationally, around 60%–70% of cancer survivors will eventually RTW, most within 12 months of initial diagnosis.3, 13-16 Continuing or returning to work after primary cancer diagnosis promotes a sense of control as well as maintaining professional identity, professional social support structures, and a sense of purpose.10, 17-21 The physical, psychological, and financial benefits employment provides are evident.11, 22, 23

There are a range of factors that may impact on a cancer survivor's RTW. Cancer type is associated with RTW, with leukemia and cancers of the lung, central nervous system, and head and neck reported to be associated with greater disability and lower employment.24, 25 It is understood that there are a myriad of challenges involved in RTW and numerous international studies have attempted to describe factors impacting on RTW for cancer survivors.3, 5, 12, 15, 19-23, 26-34 Factors, including workplace relationships, educational level, sociodemographic factors, social supports, personal finances, and presence of comorbidities, have been identified; however, evidence regarding the impacts of these social determinants in either facilitating or hindering RTW is mixed.3, 5, 12, 15, 19, 20, 26, 28-33 Understanding the RTW experience of cancer survivors, and particularly factors that impede RTW, is needed to enable identification of survivors who may be vulnerable to poorer employment outcomes and also to inform design and development of interventions or supportive resources to support people to RTW.

Internationally, numerous systematic reviews investigating RTW have been conducted involving various cancer types3, 5, 21, 27, 29, 30, 34; however, to our knowledge, no systematic review has been conducted investigating social determinants and nontreatment, non-cancer-related variables, and the impact on RTW in Australia has been conducted.

The review focuses on the Australian setting only as we recognize that the RTW experience varies greatly across different countries due to differences in health care systems, availability of welfare, health insurance coverage, and workplace discrimination laws—differences which would render a synthesis of international findings of limited practical use in informing meaningful change. The review excluded cancer-related variables (such as cancer type) and treatment-related variables (e.g., types of treatment, duration of therapies), as we were particularly interested in understanding potential disparities and inequities by virtue of social determinants (which could flag people at risk) to support RTW.

The aim of this systematic review was to identify any nontreatment, non-cancer-related variables that impact on RTW in Australian cancer survivors.

2 METHODS

This systematic literature search was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.35 The review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews—PROSPERO (registration number CRD42020190766).

2.1 Search strategy

Literature was searched using Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE (Ovid)), Psychological Information Database Medical, Psychiatry, Mental Health Disorders (PsycINFO), The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Publisher Medline (PubMed), and Google Scholar. The search was run in September 2020 without date restrictions and updated in December 2021. Searches were run across all databases using identified keywords and index terms as determined from scoping searches. Keywords describing “cancer survivor” were combined with keywords describing “RTW,” and our results were limited to Australian studies (see Supporting Information 1 for the EMBASE search strategy). Reference lists from included articles were searched manually to identify any additional studies.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they1 included adults (≥18 years of age) living post diagnosis of malignancy2; included quantitative data related to nontreatment, non-cancer-related variables impacting on RTW3; and included only Australian participants4; which were written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Studies were excluded if they did not specifically relate to RTW. For the purposes of this study RTW necessitated workforce participation prior to a cancer diagnosis. Studies that did not demonstrate pre-diagnosis work participation were excluded.

2.3 Study selection

Titles and abstracts of the articles were screened by D.F. Full-text articles were imported into EndNote and screened for inclusion by two reviewers, D.F. and K.L. Any disagreements were resolved by a third independent reviewer, M.J. Inclusion, and exclusion of studies were confirmed by D.F., K.L., and M.J.

2.4 Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using study design-specific tools as per guidelines by the Joanna Briggs Institute.36 Two reviewers, D.F. and K.L., independently assessed the risk of bias, with any disagreements resolved through discussion and consultation with M.J. Studies were deemed to be of moderate quality if they met ≥50% of eligible quality criteria, and high quality if they met ≥75% of eligible quality criteria. No studies were excluded based on quality.

2.5 Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted from each study regarding study characteristics (design, population, recruitment period, study location, and outcomes identified) as well as participant baseline characteristics (sociodemographic data, type of cancer, comorbidities and health and lifestyle information, work status, and work demographics). Quantitative assessment of demographic, work-related, or any other non-cancer, nontreatment variables as described that were associated with RTW were also extracted. Quantitative data describing variables associated with RTW in Australian cancer survivors were combined into categories based on similarity in concepts being measured and presented using narrative synthesis and presented in tables.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study selection

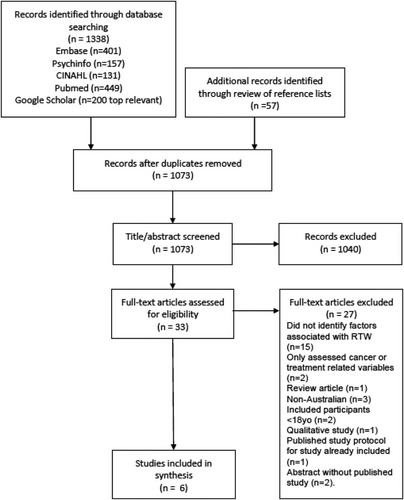

In total, 1338 records were identified through database searching and a further 57 studies identified through manual checking of reference lists (Figure 1). Three hundred and 22 duplicates were removed, leaving 1073 studies to be reviewed. After title and abstract review, 33 studies proceeded to full-text review. Application of study inclusion criteria identified 27 studies not suitable for inclusion. Six studies were found to be eligible and included in final analyses.

3.2 Study characteristics

Of the six included publications, four were cohort studies37-40 and two were cross-sectional studies41, 42 (Table 1). Three articles studied colorectal cancer patients,37, 38, 40 one study included patients with a diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme,39 one study included patients with human papillomavirus associated oropharyngeal cancer,42 and the remaining study included a variety of malignancies.41 Two articles were publications on the same cohort—the Working After Cancer Study—an observational population-based study of middle-aged Queensland workers diagnosed with colorectal cancer and their RTW experiences.38, 40 Three articles were single institution studies39, 41, 42 and the remainder state-wide, Queensland-based studies.37, 38, 40 All studies were published between 2008 and 2020. The number of included participants in these studies ranged from 19 to 975.

| Study | Design | Participants | Cancer type | Instruments | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gordon (2008)37 | Cohort 20–80 years | N = 975; male = 621 (64%) Mean age 60 (SD 10.4) Queensland colorectal cancer registry Recruited 2003–2004 |

Colorectal | Self-reported survey data at baseline and 12-month post diagnosis | Sociodemographics, health behaviors, comorbidities, cancer treatment, health-related QOL, work participation |

| Gordon (2014)38 | Cohort 45–64 years | N = 239; male = 160 (67%) Mean age 56 (SD 5.5) Queensland colorectal cancer registry Recruited 2010–2011 |

Colorectal | Structured telephone interviews at 6 and 12-month post diagnosis | Sociodemographics, work participation information |

| Gzell (2014)39 | Cohort 18–70 years | N = 112; male = 75 (67%) Mean age 56 (18–70) Northern Sydney Cancer Centre Recruited 2007–2011 |

Glioblastoma | Clinical details recorded at baseline, 6 and 12 months post diagnosis | Baseline sociodemographics, treatment details, performance status, and work participation information Employment status up to 12-month post diagnosis |

| Lynch (2016)40 | Cohort 45–64 years | N = 187; male = 122 (65%) Mean age 57 (52,61) Queensland colorectal cancer registry Recruited 2010–2011 |

Colorectal | Structured telephone interviews and postal surveys at 6 and 12-month post diagnosis | Sociodemographics, work participation information, data related to health behaviors |

| Markovic (2020)41 | Cross-sectional 20–65 years | N = 19; male = 5 (26%) Mean age 51 (44,55) Outpatient clinic at Blacktown Cancer and Hematology Centre, Western Sydney, NSW Recruited July—October 2019 |

Breast (11), prostate (2), colorectal (1), lung (1), brain (1), head and neck (1), uterus (1), and unknown (1) | Anonymous, self-reported cancer and work survey instrument | Sociodemographics, cancer, and work participation information |

| Morales (2020)42 | Cross-sectional 18–64 years | N = 68; male = 61 (90%) Mean age 54 (SD 6.8) Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Victoria Recruited February–April 2018 |

Oropharyngeal cancer | Paper-based survey had completed curative treatment ≥4 months ago | Sociodemographic data, work participation information, the exploration of factors related to decision to return to work |

The mean age of participants ranged between 51.0 and 60.2 years with a male predominance in all but one study. A wide variety of baseline sociodemographic, work, financial, and general health data points were gathered by each study with little overlap between studies.

3.3 Risk of bias

All six papers were assessed as moderate to high quality (see Table 2).

| Cross-sectional studies | Markovic (2020)41 | Morales (2020)42 |

|---|---|---|

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Yes | Yes |

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | Yes |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes |

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Yes | Yes |

| Were confounding factors identified? | Yes | No |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | No | No |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes |

| 7/8—high quality | 6/8—high quality |

| Cohort studies | Gordon (2008)37 | Gordon (2014)38 | Gzell(2014)39 | Lynch(2016)40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? | NA | No | NA | NA |

| Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups? | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were confounding factors identified? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Were groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Was the follow-up time reported and sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was follow-up complete, and if not, were the reasons for loss to follow-up described and explored? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Were strategies to address incomplete follow-up utilized? | No | Yes | NA | No |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 8/9—high | 9/10—high | 5/8—moderate | 7/9—high |

Both cross-sectional studies41, 42 were of high quality; however, neither study explored the potential impact of confounding variables on results.

Three of the four cohort studies were deemed to be of high quality.37, 38, 40 The lack of a control group in all but one of the included papers meant items 1 and 2 on the cohort appraisal checklist were deemed not applicable and not included when grading these studies. It is noted that Gordon et al.37 did not adequately address incomplete follow up. Gordon et al.38 did not recruit the groups from the same population (cancer group was drawn only from Queensland, whereas comparison group was drawn from a secondary nationwide general population) and Lynch et al.40 lacked complete follow up and failed to investigate the reasons for this.

The final cohort study—Gzell et al.39—was graded moderate quality due to a lack of identifying or managing confounding factors and was unclear whether outcomes were measured in a valid or reliable way.

3.4 Factors associated with RTW

There was substantial heterogeneity between the included studies regarding the exploration of factors associated with RTW, which precluded the synthesis of data across studies. We describe the consistencies found between studies (where possible) under the headings of “sociodemographic factors,” “work-related factors,” “heath-related factors,” and “financial factors.”

3.4.1 Sociodemographic factors

Five papers examined age in relation to RTW37, 38, 40-42 (see Table 3A). Gordon et al.38 identified a weak association between older age and lower RTW that persisted when adjusting for confounders. An earlier study based on Queensland colorectal cancer survivors, Gordon et al.,37 found that older age negatively impacted RTW for men but not for women. Markovic et al.,41 in their small study of just 19 participants, found the opposite—their older participants were more likely to RTW. Two papers found no association between age and RTW.40, 42 Markovic et al. was the only study to investigate unpaid domestic work and reported fewer hours of unpaid work were positively associated with RTW.41

| A. Sociodemographic factors | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Impact on RTW |

| Older age | Positive impact on RTW: Markovic (2020)41

|

Negative impact on RTW: Gordon (2008)37

|

|

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2008)37—female cohort | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Morales (2020)42 | |

| Gender | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Morales (2020)42 | |

| Metropolitan residence | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Morales (2020)42 | |

| Higher educational level | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2008)37 | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Morales (2020)42 | |

| Married/partnered | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2008)37 | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Morales (2020)42 | |

| Partner employed | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Presence of children in household | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Caring roles | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Less unpaid work outside workplace | Positive impact on RTW: |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| N = 19, working group 10.6 h/week vs. leave group 15.0 h/week | |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: no studies | |

| Higher number of people in household | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| B. Work-related factors | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Impact on RTW |

| Fewer work hours per week | Positive impact on RTW: Markovic (2020)41

|

Negative impact on RTW: Gordon (2008)37

|

|

| No association with RTW: no studies | |

| Work autonomy | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW:Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Longer duration of employment with current employer | Positive impact on RTW:Markovic (2020)41

|

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Size of employer | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Work schedule | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Type of contract | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Workplace type | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Morales (2020)42 | |

| Occupation group | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Challenging work demands/heavy physical work | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2008)37 | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Commute time | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| C. Health-related factors | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Impact on RTW |

| Higher number of comorbidities | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

Negative impact on RTW: Gordon (2008)37

|

|

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2008)37—women | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Lower BMI | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

Negative impact on RTW:Gordon (2014)38

|

|

| No association with RTW: | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Eating well | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Alcohol consumption | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Smoking status | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Physical activity | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Longer sleep duration | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

Negative impact on RTW: Lynch (2016)40

|

|

| No association with RTW: no studies | |

| D. Financial factors | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Impact on RTW |

| Not having private health insurance | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

Negative impact on RTW:Gordon (2008)37

|

|

| No association with RTW: no studies | |

| Personal insurance | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

Negative impact on RTW: Gzell (2014)39

|

|

| No association with RTW: | |

| Markovic (2020)41 | |

| Higher household income | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

Negative impact on RTW:Gzell (2014)39

|

|

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

| Lynch (2016)40 | |

| Higher personal income | Positive impact on RTW: no studies |

| Negative impact on RTW: no studies | |

| No association with RTW: | |

| Gordon (2014)38 | |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; RTW, return to work.

Other variables that were investigated but not found to influence RTW included gender, place of residence, education level, relationship status and employment of partner, and number of people in the home and caring roles (Table 3A).

3.4.2 Work-related factors

Two studies investigated association between hours worked pre-diagnosis and RTW. Gordon et al. reported a weak association between fewer hours worked prior to cancer diagnosis and lower RTW 1-year post diagnosis for men only.37 Results from Markovic et al. suggest that fewer work hours per week pre-diagnosis were associated with higher rates of RTW; however, this study had a very small sample size.41

Length of employment before diagnosis was assessed by two studies; Markovic et al.41 found it to be weakly associated with higher RTW, whereas Gordon et al.38 found no association with RTW.

Other variables that were investigated but not found to influence RTW included the size of employer (number of employees), work schedule, work autonomy, contract and workplace type, challenging and physically demanding work, and commute time (Table 3B).

3.4.3 Health-related factors

Comorbidities were investigated in three papers37, 38, 40 with Gordon et al.37 reporting a strong association between having three or more comorbidities and lower RTW 1 year post diagnosis; but only in men and the association did not persist when adjusting for baseline covariates (Table 3C).

A weak association between lower body mass index and lower RTW at 12-month post diagnosis was identified by Gordon et al.,38 which persisted in multivariable analysis; this result was not replicated in the analysis by Lynch et al.40 and was not assessed in other studies (Table 3C).

One study assessing health behaviors and RTW looked at sleep duration. Lynch et al.40 reported a strong association between longer than recommended sleep duration of more than 9 h per night and lower RTW or reduced work hours greater than 4 h per week at 12-month post diagnosis. This result persisted when controlling for the type of cancer; however, the authors did not attempt to control for other factors.

Other variables that were investigated but not found to influence RTW included physical activity, dietary, alcohol, and smoking habits.

3.4.4 Financial factors

Financial factors associated with RTW included health and income insurance coverage and personal financial support. Not having private health insurance was associated with work cessation for both men and women by Gordon et al.,37 and this influence persisted when adjusting for other variables (Table 3D). Having personal income insurance negatively influenced RTW at 12-month post diagnosis reported by Gzell et al.39 Of the patients without neurological deficits who had not RTW at 12 months one fifth reported that access to insurance benefits was a factor in their decision to not RTW. Gzell et al. reported that where financial support was available from spouses or other family members, 40% of participants had not RTW at 12-month post diagnosis.39

Two papers (reporting on the same cohort) examined income and RTW. Neither Gordon et al.38 nor Lynch et al.40 found an association between household income and RTW. Personal income was found to have no association with RTW reported by Gordon et al.38 (Table 3D).

4 DISCUSSION

This systematic review aimed to identify the non-cancer, non-therapy-related variables that are associated with RTW in Australian cancer survivors. We identified factors that were associated with RTW in this population, though found little consistency in findings between studies.

International literature suggests demographic and social factors that may be associated with a higher likelihood of RTW include younger age,3, 15, 29, 43, 44 higher level of education,3, 5, 29, 43 male gender,3, 44 continuity of care across hospitals,3 and friends and family support.3, 5, 15, 19, 20, 26, 28, 30, 34, 45 Factors associated with lower likelihood of RTW include older age,5, 28, 32, 43, 44, 46, 47 female gender,5, 15, 32, 43, 44 and lower levels of education.5, 29, 32, 46 Bates et al., 11 in a paper exploring workforce participation (rather than RTW and so did not meet inclusion criteria for this review), demonstrated that having cancer and not being in the workforce was 3.73 times more likely in those without a tertiary education. The present review found evidence for the association of older age and lower likelihood of RTW among Australian cancer survivors but did not show a consistent association for gender, place of residence, education level, relationship status and employment of partner, and number of people in the home and involvement in caring roles.

Communication between employer and employee is vital to make RTW a success and involves negotiating needs, overcoming barriers, acknowledging and accepting compromise, and rebuilding confidence by providing the right support.21 Work-related factors in the literature that may be associated with higher RTW include flexibility in resuming work responsibility,3, 28, 45 less stressful work,45 work that matches physical and cognitive ability,45, 48 cancer disclosure to colleagues/employer,3, 45, 19 higher number of work hours,5, 43 self-employment,45 responsibility/loyalty to workplace,26, 45, 19 greater company size,5 greater level of communication with employer,20, 28, 30 positive work environment,20, 28, 30 fear of being fired,19 and duration of employment.26 Findings from the current review consistent with findings from the above literature are fewer hours of unpaid work, fewer weekly work hours pre-diagnosis and length of employment. Working environment, manual work, physical exertion,3, 5, 15, 32, 34, 45, 47, 48 attitude of coworkers, less accommodation and support in workplace,3, 15, 20, 28, 29, 44, 45 perceived employer discrimination, psychological or self-perceived constraints,3, 28, 30, 32, 34, 44, 45, 49 employed >5 years,5 opting instead for retirement,3, 19, 43 difficulty with transportation,32, 48 and union membership3, 32 have been reported to be associated with less likelihood of RTW. In relation to these findings, this study found no evidence that the size of employer, work schedule, work autonomy, contract and workplace type, challenging and physically demanding work, and commute time is associated with RTW in Australia.

Health care costs for cancer are reported to be five times higher than for non-cancer conditions.29 Cancer presents a serious challenge to family finances and may be the dominant reason behind decisions on RTW.20, 21, 26, 45, 19, 48, 49 Other frequent reported factors positively associated with RTW include being free from financial concerns,45 higher income,5, 29 length of sick leave available,3 and health insurance tied to employment.19 Other literature suggests that low income,3, 5, 28, 32, 47 lack of employer benefits (leave of absence),5 access to adequate sick leave benefits,45 inadequate occupational health care,5 and family able to provide financial support19 may be associated with a lower likelihood of RTW. Our review noted that not having private health insurance and having personal income insurance and financial support from spouse or family members may result in a lower chance of RTW; however, the mechanisms behind these observations are unclear. It may be that not having health insurance (in an Australian setting) is an indication of greater socioeconomic disadvantage, which may indicate less job security, flexibility, or control around working conditions.50 Household income, however, was not associated with RTW in the present review, which suggests having private health insurance may be associated with benefits outside of socioeconomic status, such as greater access and usage of cancer rehabilitation and survivorship services, which may assist in RTW.51 The impact of private health insurance on RTW and other survivorship outcomes warrants further investigation.

Interventions to assist people to RTW following cancer treatment have been developed, including inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation programs, and various supportive care interventions comprised education and counseling (reviewed in Refs. [46, 52]); however, the evidence of benefit of these interventions on RTW is mixed and findings limited by study design (i.e., lack of randomized controlled trials). A consistent feature and criticism of past interventions is focusing interventions on survivors, with little to no involvement of employers in RTW initiatives.46 Further work is needed to understand the impacts of the various work, health, demographic, and financial-related factors on RTW described in this review and to design interventions that are appropriately targeted, accessible, and include all the necessary stakeholders, including employers.

There is scope for further Australian-based research looking to identify variables that are associated with RTW. Subsequent research should be carried out in populations where cancer and treatment-related toxicity is relatively homogenous to allow the greatest practical applicability within Australian society. There is also a need for greater understanding of the variables that influence disparities in RTW. A greater understanding of these variables will help to identify vulnerable groups most in need of support and intervention.

4.1 Strengths and limitations of the review

Application of inclusion criteria resulted in six papers from five studies, a small number given the importance of RTW in cancer survivorship. Searching of multiple databases and the reference lists of included papers allows some confidence that all appropriate research was included in this review and that our conclusions are based on current available evidence in Australia.

We applied a strict definition of RTW in this study choosing to examine RTW as a marker of functional recovery in cancer patients who have been required to cease or decrease their paid work hours during their acute phase of treatment. We acknowledge that this has excluded papers detailing the workforce participation of Australian cancer patients. Lack of a consistent definition and measurement of RTW, lack of consistency in variables examined by each study also limits the synthesis of our findings.

Our review was designed to answer a specific question that we believe will help to guide further research and build supports for cancer survivors. However, limiting this study to only include social determinant factors (and any other non-cancer and nontreatment-related factors) in Australian populations did narrow the scope of the review and limit study inclusion. Three of the included studies focused on colorectal cancer survivors, resulting in overrepresentation of this survivor group and limiting generalizability of our findings to other cancer types.

Our intention was to explore sources of disparity and inequality in employment outcomes in Australian cancer survivors in the hope that we can focus future research and interventions on identifying sociodemographic risk factors impacting on RTW in cancer survivors in Australia. Paucity of results, as demonstrated by this systematic review, has highlighted the need for further research in this important area.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This review included six papers that addressed non-cancer, nontreatment factors associated with RTW in Australian cancer survivors. A number of demographic, health, work, and financial factors were identified as impacting on RTW; however, there was little consistency across studies. Generalizability of findings is limited by a lack of representation of survivors from a range of cancer types. This review highlights an important knowledge gap, with further research needed to understand factors that may impact upon RTW for cancer survivors, which may inform development of targeted support to help survivors RTW. Given the unique health, welfare and workplace conditions in Australia, further the exploration of RTW should be undertaken within Australia. Studies should include survivors with a range of cancer diagnoses, cancer types prevalent in people of working age, and should focus on factors that have been identified in the limited Australian, and more extensive international, literature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Investigating Variation in Victorian Cancer Survivors Study Team (INVAVICUS). This study was conducted as part of a grant, HSR19001, Identifying statewide disparities in cancer survivorship, funded by the Victorian Cancer Agency.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.