Physical activity behaviors in cancer survivors treated with neurotoxic chemotherapy

Abstract

Aim

There are many barriers to physical activity among cancer survivors. Survivors treated with neurotoxic chemotherapy may develop chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) and experience additional barriers related to sensorimotor and mobility deficits. This study examined physical activity behaviors, including physical activity predictors, among cancer survivors treated with neurotoxic chemotherapies.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of 252 participants, 3–24 months after neurotoxic chemotherapy, was undertaken. Physical activity was self-reported (IPAQ). CIPN was self-reported (FACT/GOG-Ntx-13), clinically graded (NCI-CTCAE), and objectively measured using neurological grading scales and neurophysiological techniques (tibial and sural nerve conduction studies). Balance (Swaymeter) and fine motor skills (grooved pegboard) were assessed. Regression models were used to identify clinical, demographic and CIPN predictors of walking and moderate–vigorous physical activity.

Results

Forty-four percent of participants did not meet recommended physical activity guidelines (≥150 min/week). Sixty-six percent presented with CIPN. Nineteen percent of participants with CIPN reported that symptoms interfered with their ability to be physically active. A lower proportion of survivors aged ≥60, with grade ≥1 CIPN or BMI ≥30, reported meeting physical activity guidelines (all p < .05). Regression models identified older age, higher BMI, and patient-reported CIPN associated with lower walking, while higher BMI and females were associated with lower moderate–vigorous physical activity. Neurologically assessed CIPN did not associate with walking or moderate–vigorous physical activity.

Conclusion

Cancer survivors exposed to neurotoxic chemotherapy have low physical activity levels. Further work should examine the factors causing physical activity limitations in this cohort and designing interventions to improve physical function and quality of life in survivors.

1 INTRODUCTION

Physical activity participation associates with numerous benefits for cancer survivors, including improved general health, sleep quality, muscle mass, quality of life, and survival.1 However, there are many barriers to participation among cancer survivors, which may reduce their ability or willingness to participate.2 Neurotoxic anticancer agents such as taxanes, platinum drugs, vinca alkaloids, or bortezomib3 are utilized to treat a significant proportion of cancer survivors. These agents are associated with the development of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), which may impair sensation, physical function, balance, and reduce quality of life.4 CIPN represents one potential barrier to physical activity, which may make exercise more challenging for survivors. Importantly, structured exercise and balance training are potential rehabilitative options for cancer survivors with CIPN5; and accordingly, participation may be important for cancer survivors treated with neurotoxic agents.

Prior studies have investigated the impact of physical activity participation on quality of life in cancer patients treated with neurotoxic chemotherapy.6 Colorectal cancer survivors who developed CIPN due to their treatment were less likely to achieve physical activity targets, compared to survivors without CIPN.7 However, limited data exist regarding risk factors for reduced general physical activity behaviors in cancer patients treated with neurotoxic anticancer agents. The primary aim of our study was to quantify physical activity behaviors among survivors treated with neurotoxic chemotherapy. Our secondary aim was to investigate whether CIPN symptoms interfered with physical activity, and to identify predictors of walking and moderate–vigorous physical activity among cancer survivors who have been treated with neurotoxic chemotherapy.

2 METHODS

2.1 Participants

Participants treated for stage I–III cancer with neurotoxic anticancer agents were recruited from hospitals in Sydney and Brisbane, Australia, between July 2018 and February 2020. Participants were assessed cross-sectionally from 3 up to 24 months after completing neurotoxic chemotherapy. The study was approved by South-Eastern Sydney Local Health District and Sydney Local Health District (RPAH zone) Human Research Ethics Committees, with informed written consent obtained from each participant. Clinical data were obtained from medical records, including cancer diagnosis information and diabetes status.

2.2 Assessment tools

Participants self-reported physical activity over the previous week using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) - Short Form, validated in patients with cancer.8 Total weekly minutes of physical activity energy expenditure (metabolic equivalent of tasks [MET]) were determined by multiplying weekly minutes of walking (×3), moderate intensity (×4), and vigorous intensity (×8) activity. Total MET-minutes per week were calculated for each intensity and summed together for the total value. One item assessed sedentary behaviors regarding daily sitting hours.8

Patient-reported CIPN symptoms were assessed using a validated patient-reported outcome measure (FACT/GOG-Ntx-13), comprising 13-items rated from “not at all” to “very much” (total score 0–52), and reverse scored, with lower scores indicating more severe CIPN.9 Participants with symptomatic CIPN were asked an additional single-item question regarding whether their CIPN symptoms impacted their ability to exercise. CIPN severity was clinically graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.0 neuropathy sensory subscale, which graded CIPN as: grade 0 (no symptoms), grade 1 (symptomatic, not interfering with daily function), grade 2 (moderate sensory symptoms, limiting daily function), grade 3 (severe sensory symptoms, limiting daily function and self-care), and grade 4 (disabling).10 CIPN was also neurologically graded using the Total Neuropathy Score-clinical and reduced versions (TNSc, TNSr, Johns Hopkins University). TNSc is a composite tool assessing upper and lower limb pin-prick sensory and vibration sensibility, deep tendon reflexes, strength, and patient-reported symptoms.11, 12 Each component is graded from 0 (normal) to 4 (severe), with the total score ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 24 (severe symptoms). Additionally, TNSr included a neurophysiological assessment of tibial motor and sural sensory nerves, using standard nerve conduction protocols,13 graded from 0 to 4, with a total composite score of 0–32.

Fine motor skills and manual dexterity were assessed using the grooved pegboard test to assess the time taken (seconds) for participants to place 25 pegs into grooved holes using the dominant hand, with two attempts taken to calculate an average time.14 Balance was assessed using a Swaymeter (NeuRA [Neuroscience Research Australia], Sydney, Australia) to calculate postural sway,15 as per prior studies.16 Participants wore a belt attached to a 50-cm rod, which recorded movements as a surrogate marker of the center of mass on an iPad, calculating total path length (mm). Participants completed four 30-s conditions with the eyes open or closed and on a flat or unstable surface (standing on a piece of foam). Total path length was calculated by summing path lengths from all conditions. For participants unable to complete any condition due to instability, a score of the cohort mean plus 3 standard deviations was utilized to calculate path length as per previous protocols.17

2.3 Data and statistical analyses

Descriptive data for non-normally distributed data as identified using the Shapiro–Walk test were presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR). Otherwise, data were presented as mean and standard deviation. Participants’ physical activity levels were classified into recommended guidelines (≥150 min/week of moderate–vigorous activity),18 and converted to total MET-minutes per week (sum of walking, moderate, and vigorous activities). Independent sample t-tests were used to compare the proportion of survivors meeting activity guidelines by CIPN grade, age, body mass index (BMI), and cancer stage. Linear regression analyses were conducted to identify clinical, functional, and CIPN symptom-based predictors of walking and moderate–vigorous physical activity (using patient-reported and neurologically graded CIPN measures [TNSc and TNSr] in separate models). Missing data were calculated using multiple imputations. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics Software V25 (IBM; Armonk, NY) and followed the STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies.19

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participant characteristics

In total, 252 participants were assessed at a median of 12 months (IQR 17) following completion of neurotoxic cancer treatment (75% female, n = 188, median age 58 [IQR 18] years; Table 1). The most common treatment agents were taxanes (62%, n = 156) and platinum agents (25%, n = 64). Sixty-six percent (n = 166) were experiencing CIPN symptoms at the time of assessment, including mild CIPN in 31.3% (n = 79; Grade 1), moderate in 29.8% (n = 75; Grade 2), and severe in 4.8% (n = 12; Grade 3].

| Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 58.0 | 18 |

| Body mass index (m/kg2) | 26.1 | 7 |

| Months since treatment | 12 | 17 |

| Physical activity (min/week) | ||

| Walking | 210 | 330 |

| Moderate | 90 | 240 |

| Vigorous | 0 | 120 |

| Total (MET-mins/week) | 1657 | 2580 |

| Sitting (hours/day) | 6 | 4 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Meeting physical activity guidelinesa | 140 | 56 |

| Sex (female) | 188 | 75 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Breast | 112 | 45 |

| Gastro-intestinal | 61 | 24 |

| Gynecological | 34 | 14 |

| Hematological | 31 | 12 |

| Otherb | 14 | 5 |

| Cancer stagec | ||

| I | 25 | 11 |

| II | 81 | 37 |

| III | 104 | 47 |

| Undefined stage I–III | 11 | 5 |

| Neurotoxic treatment agents | ||

| Taxane | 156 | 62 |

| Platinum | 64 | 25 |

| Vincristine | 20 | 8 |

| Bortezomib | 11 | 4 |

| Thalidomide | 1 | .4 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 23 | 9 |

- Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

- a Recommended physical activity guidelines are ≥150 min/week of moderate–vigorous physical activity (walking, moderate, vigorous).18

- b Other cancers include testicular (n = 5), lung (n = 3), prostate (n = 3), and urothelial (n = 3).

- c Cancer stage for solid tumors.

3.2 Physical activity levels after neurotoxic anticancer treatment

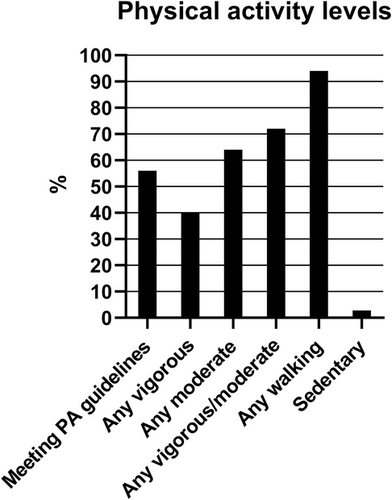

Forty-four percent of the cohort (n = 112) were not achieving recommended guidelines after receiving neurotoxic agents (Figure 1). When asked about physical activity in the previous week, 40% (n = 102) reported undertaking any vigorous intensity activity, 64% (n = 162) reported any moderate-intensity physical activity, and 94% (n = 238) reported undertaking any amount of walking (for >10 min increments). Twenty-eight percent (n = 70) did not participate in any moderate- or vigorous-intensity physical activity, while 2.8% (n = 7) were completely sedentary.

3.3 CIPN symptoms impairing ability to be physically active

Participants with CIPN were asked whether they perceived that their CIPN symptoms impaired their ability to be physically active. A total of 19% (n = 29) of participants with CIPN reported that they felt their CIPN symptoms affected their ability to exercise. These participants demonstrated more severe CIPN as assessed by clinically graded NCI-CTCAE (p < .001) and patient-reported FACT/GOG-Ntx-13 measures (p = .003), compared with participants with CIPN who did not report exercise interference, despite not experiencing worse balance (p = .10). There were no differences in physical activity participation between participants who reported CIPN interfering with ability to exercise and those who did not across any intensity (walking: p = .71, moderate: p = .21, vigorous: p = .83, total MET-min/week: p = .44), although the impaired exercise group reported higher daily sitting hours (p = .03).

3.4 Physical activity levels by clinical characteristics

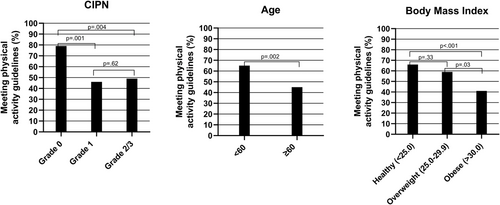

Physical activity levels were analyzed by clinical characteristics, including age, severity of CIPN, BMI, and cancer stage (Figure 2). A higher proportion of younger participants met physical activity guidelines compared with older participants (<60 years = 65% [n = 86] vs. ≥60 years = 45% [n = 54], p = .002), despite no difference in CIPN severity (p = .13). Among participants with no CIPN (grade 0), 79% (n = 61) met guidelines. This proportion was higher than those with mild (grade 1; 46% [n = 36], p = .001) and moderate/severe CIPN (grade 2/3; 49% [n = 43], p = .004). There was no statistical difference in proportion of patients meeting guidelines between participants with mild versus moderate/severe CIPN (p = .62). A lower proportion of obese participants (≥30.0 kg/m2; 41% [n = 28]) met guidelines compared with healthy weight (<25.0 kg/m2; 66% [n = 64], p < .001) and overweight participants (25.0–29.9 kg/m2; 59% [n = 44], p = .03). However, there was no difference between healthy weight and overweight participants (p = .33). There was no difference in the proportion of participants diagnosed with stage I/II disease (61%, n = 67) compared to stage III disease (53%, n = 57, p = .28) meeting guidelines. There were no differences in physical activity between patients treated with taxanes compared to platinum agents, the two most common treatment types (p = .85).

3.5 Predictors of physical activity among patients treated with neurotoxic agents

To further examine predictors of walking and moderate–vigorous physical activity, linear regression analyses were conducted. Factors contributing to higher walking levels included younger age (p = .026), lower BMI (p = .021), and lower patient-reported CIPN severity (p = .027; Table 2). Factors contributing to higher moderate–vigorous physical activity included male gender (p = .003) and lower BMI (p = .031). Factors that did not statistically contribute to predicting either intensity model included time since treatment, diabetes, fine motor function, and balance (all p > .05). When analyzing the model using neurologically graded CIPN (TNSc), and accounting for nerve conduction studies (TNSr) instead of a patient-reported questionnaire, there was no significant contribution of CIPN severity in either physical activity intensity models (Tables S1 and S2).

| Walking | Moderate–vigorous | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | p-Value | B (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age | −12.0 (−37.1 to −.5) | .026* | −9.1 (−33.9 to 15.7) | .47 |

| Sex | 21.1 (−262.0 to 304.3) | .88 | −1002.2 (−1657.9 to −346.5) | .003* |

| Body mass index | −25.4 (−46.9 to −3.8) | .021* | −53.9 (−102.8 to −5.1) | .031* |

| Months post treatment | 6.3 (−9.7 to 22.4) | .44 | 14.8 (−22.4 to 51.9) | .44 |

| Diabetes | −58.3 (−519.9 to 403.2) | .80 | −203.5 (−1276.0 to 868.9) | .71 |

| Fine-motor skills (grooved pegboard; seconds) | −.67 (−6.3 to 4.9) | .82 | −8.9 (−22.1 to 4.2) | .18 |

| Balance (path length, mm) | −.28 (−.87 to .32) | .36 | −.64 (−2.4 to 1.1) | .45 |

| Patient-reported CIPN (FACT/GOG-Ntx-13; 0–52) | −22.0 (−41.5 to −2.5) | .027* | −8.9 (−55.6 to 37.7) | .71 |

- Note: Results are presented with regression coefficients (B) and 95% confidence intervals. Negative sex value denotes female gender, positive diabetes indicates presence of condition, lower FACT/GOG-Ntx-13 score indicates greater symptoms, higher balance score indicates poorer balance, higher grooved pegboard time indicates reduced fine-motor skills.

- * p < .05.

4 DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to examine physical activity behaviors in cancer survivors treated with neurotoxic chemotherapies. Given the associations between moderate–vigorous physical activity and cancer survival,21 physical function,22 quality of life,22 mobility,23, 24 cardiorespiratory fitness,5, 25, 26 and muscle strength,5, 25, 26 it is critical to identify barriers to physical activity in cancer survivors to encourage behavior change.

Importantly, 28% of our cohort did not participate in any moderate–vigorous physical activity. Although this proportion is similar to the general Australian population,27, 28 it could be argued that physical activity participation is more crucial among cancer survivors given their medical sequelae from treatment and the potential benefits. Physical activity levels vary widely among cancer survivors based on cancer type, age, and other clinical factors, with previous reports of 22%–93% of cancer survivors meeting physical activity guidelines.29-31 Overall, comparing physical activity levels between studies is difficult due to limitations, including the use of self-reported physical activity, which may introduce intensity misinterpretation32 or overreporting,33 although self-reported physical activity has been shown to correlate moderately with accelerometer data.34

A secondary aim of our study was to examine predictors of physical activity, including CIPN. However, it should be noted that a limitation of our study is the cross-sectional design and lack of prediagnosis physical activity levels,39 which likely represents an important predictor of posttreatment activity.

Our analysis found associations between patient-reported CIPN, BMI, age, female gender with physical activity. Less obese patients met guidelines compared with overweight patients, similar to previous research in cancer survivor cohorts.40-42 Importantly, obese cancer survivors have been shown to experience more severe CIPN symptoms,43 have reduced physical function,42 and diminished quality of life,40 representing an important group to promote behavior change. Similarly, older survivors may benefit from physical activity interventions to mitigate their risk of muscle deconditioning and falls.2, 44, 45 Finally, females performed less moderate–vigorous physical activity than males as previously reported.46 It should be noted that our cohort was 75% female, due to the large number of paclitaxel-treated breast cancer patients, which potentially affects the representativeness of our results.

We found that patient-reported CIPN severity was associated with reduced walking activity. CIPN may produce balance and gait dysfunction, loss of sensory feedback in lower limbs, and increased anxiety surrounding falls risk,16, 38 which may affect ability to be physically active. CIPN is also often associated with co-morbidities and higher BMI,35, 38 which may further compound inactivity. However, while prior cross-sectional studies have identified an association between low physical activity and greater severity of CIPN,30, 35, 36, this remains an association and further studies would be required to examine causal links. Further, exercising from the onset of chemotherapy may have promising potential to ameliorate the onset or severity of CIPN,37 which is another factor that a large-scale prospective study could address.

Interestingly, while patient-reported CIPN was associated with total walking amount, we did not find this association with neurologically graded CIPN. This discrepancy between patient-reported CIPN and clinically graded tools, including the TNSc, has been identified previously,47 suggesting that these tools identify different facets of neuropathy. This highlights the importance of assessing patient-reported symptoms, particularly given functional and psychological factors that may be critical determinants of participation in physical activity.48

The present study was a multisite, large-scale sample using validated assessment tools, including objective, clinical, and patient-reported measures. While we included a broad-spectrum cohort of patients exposed to neurotoxic chemotherapy, this limits our ability to make specific cancer- or treatment-based conclusions. Our findings may not be generalizable to patients with other complex medical conditions or who are disabled by therapy and are less able to participate in research. Our findings are limited by using patient-reported physical activity measures, which can be overcome by using objective measures such as accelerometers. We did not investigate prediagnosis physical activity, which has been shown to correlate with posttreatment physical activity regardless of symptoms and barriers presented.49 Further, it is also plausible that other factors, including social support and self-efficacy, are key moderators of physical activity behavior.20

In total, cancer survivors treated with neurotoxic agents may be at risk of reduced physical activity participation and should be motivated to safely increase their physical activity levels, given its potential to improve functional deficits and quality of life. Further work should canvas the primary causal factors related to reduced physical activity in this cohort and design appropriate interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participants for providing their time for this study, all In Focus study collaborators, and UNSW Stats Central for assisting with data analysis. Cancer Institute NSW Program, Grant Number: 14/TBG/1-05; National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Project, Grant Number: 1080521; NHMRC Career Development Fellowship, Grant Number: 1148595

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

David Mizrahi, Susanna B. Park, and David Goldstein were responsible for the conceptualization and design of the study. David Mizrahi and Susanna B. Park were responsible for data analysis and preparing the tables and figures. David Mizrahi, Terry Trinh, Hannah C. Timmins, Tiffany Li, David Goldstein, Michelle Harrison, Gavin M. Marx, Elizabeth J. Hovey, Craig R. Lewis, Michael Friedlander, and Susanna B. Park were responsible for data acquisition and collection. All authors were responsible for writing and editing of the manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study was approved by South-Eastern Sydney Local Health District and Sydney Local Health District (RPAH zone) Human Research Ethics Committees.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to conditions set out by the approving ethics committee but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.