Out of stock: A brief clinical reference for rough equivalency of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) ± glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor agonists for A1c and weight reduction in people with type 2 diabetes

Abstract

Highlights

- Despite the common practice of switching patients from one medicine to another—to improve efficacy, safety, or tolerability—guidance on how to do so is uncommon. During this time of global shortage of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) ± glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) RA therapies, this research letter offers a quick clinical reference of rough equivalency between GLP-1 ± GIP RA for A1c and body weight reduction in people with type 2 diabetes.

1 INTRODUCTION

The recent article in the Journal of Diabetes by Jung et al highlights the importance of persistence to glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) therapy for glucose control and how persistence has improved in recent years.1 GLP-1 RA therapy has gained prominence in guidelines owing to their robust A1c reduction and cardiovascular benefits.2 They also harbor patient-friendly attributes like weight reduction and no increased risk of hypoglycemia. Nevertheless, a new challenge now threatens persistence of GLP-1 ± glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) RA use: supply.

Twice daily, fixed-dose injectable exenatide was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an adjunct to diet and exercise for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in April 2005. Its approval marked the first in the newly created class of GLP-1 RA. Others soon followed, but their collective utilization remained low (ie, <10% of total prescribed diabetes medicines) until the approval of high-dose semaglutide (2.4 mg weekly; a GLP-1 RA) for chronic weight management in June 2021. Higher than expected demand coupled with unforeseen manufacturing hiccups lead to a national shortage in less than 6 months.

Patients and prescribers quickly turned to a lower dose of semaglutide (1 or 2 mg weekly) approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, using it off label for chronic weight management. By early 2022, injectable semaglutide—by any brand name—was largely unavailable creating overflow demand for like products, namely dulaglutide (an injectable weekly GLP-1 RA) and tirzepatide (an injectable weekly GLP-1 ± GIP RA). It did not take long before these medications also became scarce. By the end of 2022, manufacturers were neither promoting, sampling, or accepting investigator-initiated studies for these medications. Supply has been forecasted to be back in stock for months now and it is still not clear if or when it will.

The manufacturing shortage of GLP-1 ± GIP RAs has resulted in rapid switching back and forth between products, largely based on what is available in pharmacies, openly threatening persistence of their use as highlighted by Jung et al. The purpose of this letter to the editor is to provide a brief clinical reference for rough equivalency of approved and commonly used GLP-1 ± GIP RAs for A1c and weight reduction in people with type 2 diabetes.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

All data are taken from pivotal trials included in the FDA-approved prescribing information. Data provided are intended to create the most like comparisons, generally as add-on to metformin only, avoiding weight increasing medications such as sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones, as much as possible (trials as add-on to insulin are not included).3-10 Comparisons between products are not the result of head-to-head clinical trials. A summary of head-to-head trials comparing limited products or doses has been previously published.11

3 RESULTS

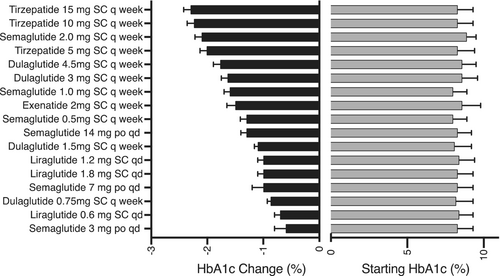

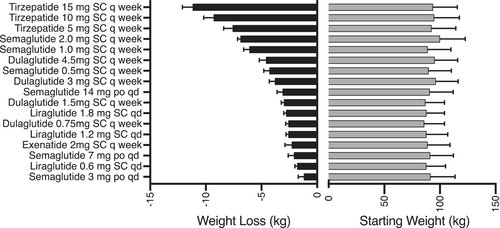

Baseline and change in A1c with GLP-1 ± GIP RA in people with type 2 diabetes is shown in Figure 1. Baseline and change in weight are shown in Figure 2. Both figures are plotted in order of reported potency to lower A1c or body weight for ease of viewing for clinicians needing to switch patients between products, presuming they are striving for similar A1c and body weight. Trials range from 26 to 56 weeks with A1c and weight mostly stable after 26 weeks. High-dose dulaglutide (3 and 4.5 mg), moderate- to high-dose semaglutide (1 and 2 mg), and any maintenance dose of tirzepatide (≥5 mg) achieved A1c reduction of ≥1.5%, whereas only semaglutide and tirzepatide consistently achieved a body weight loss of ≥5 kg. Gastrointestinal adverse events (AE) were the most common AE in all trials, ranging from 35% to 65% and scaled with potency for A1c and weight reduction. Warnings and contraindications are largely consistent between products.

4 DISCUSSION

GLP-1 ± GIP RA therapy has rapidly risen up the preferred utilization pathway in guidelines in recent years. First as the preferred injectable before basal insulin owing to noninferiority for A1c reduction without risk of hypoglycemia, next for their cardiovascular benefits, and most recently for their impressive ability to reduce body weight.2 Collectively, the glycemic and nonglycemic benefits of these incretin mimetics for people with type 2 diabetes are clear. The unforeseen challenge now is finding them.

The sole purpose of this letter to the editor is to improve persistence of GLP-1 ± GIP RA use by providing clinicians with a “cheat sheet” of rough equivalency of these medicines for A1c and body weight reduction until the supply issue can be resolved. Many primary care providers, in particular, may not be aware of daily injectable or oral GLP-1 RA, nor of the many approved maintenance doses that exist. It should be noted, at the time of this letter, no supply issue exists for the daily injectable or oral GLP-1 RA. Further, it is important to point out that adverse side effects, especially those gastrointestinal in nature, tend to scale with potency of the medications for A1c and weight reduction. Hence, switching to a less potent medication may ease side effects, although individual response is difficult to predict. Conversely, repeating uptitration may not be necessary when switching patients between comparably potent GLP-1 ± GIP RA who are tolerating their therapy well.

It is not uncommon in the practice of medicine to switch patients from one drug to another to improve efficacy, tolerability and safety. Despite the common practice of switching medications, guidance on how to switch is rare. Currently, there is a global shortage of GLP-1 ± GIP RA therapies, as well as no guidance on how to switch patients between them. May the current data provide some assistance with the latter.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding supported this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Leigh Perreault has received person fees for speaking and/or consulting from Novo Nordisk, Elli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Neurobo, Medscape, WebMD, and UpToDate. Bryan C. Bergman has no conflicts to declare.