Exploring the Impact of a Naturalist Training Camp on Biodiversity Conservation Willingness and Mental Well-Being

博物达人训练营对参与者生物多样性保护意愿和心理健康的影响

Editor-in-Chief: Binbin Li | Handling Editor: Yue Li

ABSTRACT

enEngaging the public in naturalist activities has been identified as a promising approach to enhancing conservation awareness and improving mental well-being; however, empirical evidence supporting this relationship remains limited. This study aimed to explore the impact of a naturalist training camp on participants' conservation attitudes and mental well-being. The 9-day camp, organized by the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG), focused on increasing participants' knowledge, social connectedness, and naturalist identity through a combination of indoor lectures and outdoor fieldwork on plants, insects, reptiles, and birds. Each session was led by expert researchers and science communicators. A mixed-methods approach was used to assess the camp's effects on 26 participants through questionnaires administered before, immediately after, and 6 months post-camp, as well as phone interviews. Quantitative analysis revealed significant improvements in participants' knowledge of biodiversity, social connectedness, perceived naturalist identity, and mental well-being, although changes in conservation attitudes were not statistically significant. Qualitative data further supported these findings, indicating that enhanced conservation willingness and mental well-being were likely influenced by increased knowledge, social connectedness, and perceived naturalist identity. Interview responses highlighted the importance of the camp's unique environment, supportive atmosphere, and the professionalism of the instructors in contributing to its success. Overall, this study underscores the value of promoting public engagement in naturalist activities as a means of addressing both biodiversity loss and mental health challenges while also advocating for ecological civilization to enhance human and environmental well-being.

摘要

zh参与博物活动被认为是提升公众环保意识和促进心理健康的有效途径, 但相关的实证研究仍较为有限。本次研究以西双版纳热带植物园举办的为期9天的博物达人训练营为例, 训练营旨在通过室内讲座和户外实地考察 (课程涵盖植物、昆虫、爬行动物和鸟类等) 提高参与者的生物多样性知识、社会联结和博物爱好者身份认同。每个课程均由专业领域科研人员和科普专家作为授课老师。研究采用混合方法, 使用问卷调查 (分别在培训前、培训结束后和六个月后进行调查) 和访谈对26名参与者进行追踪评估。定量研究显示, 参与者的生物多样性知识、社会联结、博物爱好者身份认同和心理健康情况在课程后都有显著提高, 但在保护意愿方面仅达到了统计学上的边缘显著性。质性数据进一步补充支持了这些发现, 研究表明增加的知识、社会联结和博物爱好者身份认同可能是提升保护意愿和心理健康的关键因素。同时, 访谈结果强调了博物达人训练营新奇的课程和环境、支持性氛围和讲师的专业性对其成功的重要作用。总体而言, 本研究凸显了通过博物教育活动促进公众参与在应对生物多样性丧失和心理健康问题方面的价值, 并呼吁通过生态文明理念促进人类和自然环境的共同福祉。 【翻译:孟义川】

Plain Language Summary

enIn recent years, getting people involved in nature-related activities, such as studying plants and animals, has been recognized as a promising way to raise awareness about environmental protection and improve mental health. However, there has been limited research on the effectiveness of this approach. This study examined the impact of a 9-day naturalist camp organized by the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden on participants' attitudes toward conservation and their mental well-being. During the camp, participants learned about plants, insects, reptiles, and birds through a combination of classroom sessions and outdoor field trips. The camp aimed to help participants feel more connected to nature while also increasing their knowledge and sense of identity as naturalists. This study used surveys and interviews to gather information from 26 participants before the camp, immediately after, and 6 months later. The results showed significant improvements in participants' knowledge of biodiversity, sense of connection with others, sense of naturalist identity, and mental well-being. Interviews highlighted the camp's unique environment, engaging course content, supportive atmosphere, and professionalism of the instructors as key factors contributing to its success. The findings suggest that engaging the public in naturalist activities can be an effective tool for environmental protection and improving mental health and that fostering naturalist identities benefits both people and the planet.

简明语言摘要

zh近年来, 鼓励公众参与与自然相关的活动, 如学习植物和动物, 被认为是提高环保意识和改善心理健康的有效方法。然而, 关于这种方法是否真的有效的研究仍然较为有限。本研究探讨了西双版纳热带植物园举办的为期9天的博物达人营对参与者的环保态度和心理健康的影响。训练营通过课堂讲座和户外实地考察, 向参与者介绍植物、昆虫、爬行动物和鸟类等类群知识, 旨在提高他们的自然知识、社会联结感和博物爱好者身份认同感。研究通过问卷调查和访谈收集了26名参与者在培训前、结束后及六个月后的数据。结果显示, 参与者的生物多样性知识、社会联结感、身份认同和心理健康都有显著提升。访谈结果表明, 训练营新奇的课程内容和环境、支持性的氛围和老师的专业性是成功的重要因素。研究结果表明, 让公众参与博物活动是保护环境和促进心理健康的有效途径, 证明了培养博物爱好者对人类和地球的共同福祉具有重要意义。

Summary

en

-

Creating a novel, family-like atmosphere and ensuring professionalism in nature education are important for promoting positive learning outcomes.

-

The naturalist training camp enhanced participants' knowledge, social connectedness, and sense of identity, with these educational outcomes demonstrating stability for at least 6 months.

-

Improvements in knowledge and social connectedness further boosted participants' willingness to engage in biodiversity conservation and enhanced their mental health, with a stronger naturalist identity contributing to this improved mental well-being.

实践者要点

zh

-

在自然教育中营造新奇性、家庭化的氛围和专业性对促进学习效果非常重要。

-

博物达人训练营提升了学员的知识、社会联结和身份认同, 课程效果具有至少半年的长期稳定性。

-

知识和社会联结的提高进一步促进了参与者的生物多样性保护意愿和心理健康的提升, 并且博物爱好者身份认同的提升提高了心理健康。

1 Introduction

Biodiversity loss is widely recognized as one of the most severe threats to humanity today (Sandra et al. 2019; Gonalves-Souza et al. 2020). Conservation education plays a crucial role in addressing the biodiversity crisis, primarily by enhancing the public's connection to nature, fostering positive attitudes toward biodiversity, and increasing willingness to protect it (Mascia et al. 2003; Folke et al. 2011; Fischer et al. 2012; Jiménez et al. 2014). The concept of biophilia, introduced by Wilson (1984), suggests that humans have an inherent inclination to love nature and living organisms as a result of evolutionary processes (Wilson 1984; Kellert and Wilson 1993). One key objective of conservation education is to rekindle this biophilic connection to biodiversity.

Mental health is also a critical concern in modern society, both in China and globally. It is defined as a state of mental well-being that enables individuals to cope with life's stresses, realize their abilities, learn well, work effectively, and contribute to their communities (World Health Organization [WHO] 2022). Globally, approximately one in eight people may experience some form of mental health problem, with depression and anxiety being among the most common, yet many individuals do not receive treatment (World Health Organization [WHO] 2024). A survey conducted with a large sample of Chinese residents revealed that 10.6% of adults experienced depression, while 15.8% reported anxiety, indicating that over 100 million people in China are affected by mental health issues (Fu and Zhang 2023). The causes of mental illness in modern society are complex, with disconnection from nature being considered a significant driver. Industrialization, urbanization, and lifestyle modernization have increasingly distanced people from nature, leading to a predominance of urban environments. Encouragingly, several studies have suggested that reconnecting with nature may be an effective strategy for improving mental well-being (White et al. 2017; Britton et al. 2020; Keller et al. 2023). Nature has been shown to aid in restoring cognitive fragility (Kaplan 1995) and reducing stress through physiological adjustment (Ulrich 1983; Ulrich et al. 1991; Bratman et al. 2015). However, questions remain about where and how nature experiences occur and how they can substantially improve mental health (Berto 2014; Joye and Dewitte 2018).

Naturalists are individuals driven by an intrinsic love for nature who actively explore various aspects of biology and the environment (Schmidly 2005; Mraz 2015). They possess a profound understanding of the natural world and often exhibit high levels of engagement and effectiveness in conservation efforts (Robbins et al. 2021). Amateur naturalists have a long-standing tradition in many developed countries, dating back to the 17th century, where they collect specimens, document observations in journals, and specialize in particular habitats or taxa (Miller-Rushing et al. 2012). In recent years, there has been a growing trend in China, particularly among younger generations, to engage in amateur naturalism. For example, it was estimated that in 2023, there were approximately 340,000 birdwatchers in Chinese mainland (China Wildlife Conservation Association [CWCA] 2024), representing just one segment of a broader community of natural history enthusiasts. The rise of the naturalist movement is seen as contributing to the advancement of ecological civilization in China (Sun 2016; Fu and Nielsen 2023), a key national strategy for sustainable development (Pan 2018). Some conservation organizations, such as the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden (XTBG), have launched naturalist training camp programs to cultivate more naturalists, promoting a broader public appreciation for nature and a stronger commitment to conservation. Additionally, amateur naturalists, with their extensive nature experiences, may positively contribute to mental well-being, a topic that warrants further exploration.

Numerous environmental education programs, including citizen science projects, nature-based field courses, and conservation volunteer initiatives, have demonstrated the capacity to effectively enhance participants' knowledge, willingness to engage in conservation, and mental well-being (Jordan et al. 2011; Krasny and Tidball 2012; Ballantyne and Packer 2009). For instance, certain citizen science initiatives have shown positive effects on participants' environmental knowledge and conservation attitudes through active involvement in scientific data collection (Bonney et al. 2009; Merenlender et al. 2016). Similarly, nature-based field courses have been associated with improvements in participants' sense of environmental stewardship and the development of a stronger environmental identity (Ernst and Theimer 2011). Furthermore, conservation volunteer programs have shown that participation in hands-on conservation activities can enhance social connectedness and contribute to mental well-being (O'Brien, Townsend, and Ebden 2010). However, most studies in this area tend to focus on one or a limited number of dimensions of educational outcomes.

The current Naturalist Training Camp at XTBG builds upon these previous initiatives by integrating multiple dimensions—knowledge acquisition, social interaction, and identity development—into a cohesive program that offers both structured educational sessions and immersive nature experiences. In this study, nature connectedness is defined as an emotional, cognitive, and experiential bond with nature, serving as the foundational framework for our examination of knowledge, social connectedness, and naturalist identity (Mayer and Frantz 2004; Capaldi et al. 2015). The XTBG camp aims to foster a holistic sense of nature connectedness by emphasizing social relationships and personal identity alongside knowledge acquisition. The incorporation of guided fieldwork and opportunities for participants to engage intensively with experts and peers distinguish the XTBG camp from other programs, creating a supportive social environment that may enhance participants' sense of belonging and identity as naturalists. This integrated approach seeks to advance previous research by explicitly addressing how the interconnected elements of knowledge, social connectedness, and identity collectively contribute to increased conservation willingness and improved well-being.

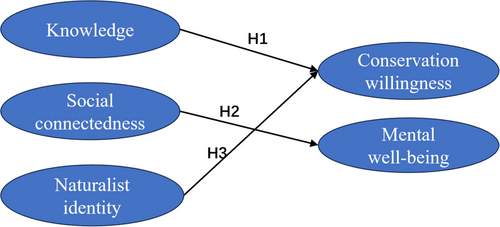

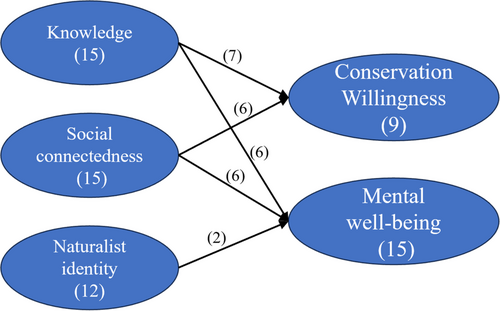

In this study, we conducted a systematic evaluation of the Naturalist Training Camp held at XTBG. The primary objective was to investigate the relationship between naturalist activities, conservation willingness, and mental well-being by examining three proposed hypotheses. First, knowledge serves as the cognitive foundation for deeper nature connectedness by fostering an appreciation and understanding of biodiversity, thereby promoting a protective attitude toward nature (Chawla 1999; Ballantyne and Packer 2005) (Figure 1, H1). Second, social connectedness is enhanced through interactions with peers who share an interest in nature, creating social bonds that provide a sense of belonging and emotional support—both of which are essential for improving mental health (Ryan and Deci 2017) (Figure 1, H2). Third, naturalist identity is cultivated through participation in nature-related activities and social roles, enabling individuals to translate their care for nature into sustained conservation actions (Stets and Biga 2003; Clayton 2003) (Figure 1, H3).

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Research Location

The study was conducted at XTBG, located in Mengla County, Yunnan Province, China. Established in 1959, XTBG is a comprehensive research institution renowned for its scientific research, species conservation efforts, and public education initiatives. It is also a popular tourist destination, both domestically and internationally. Encompassing an area of approximately 1125 hectares, the garden houses over 13,800 species of live plants across 39 specialized outdoor living collections and preserves around 250 hectares of pristine tropical rainforest. Furthermore, XTBG serves as a habitat for a diverse array of wildlife and insects, including 63 mammal species, 319 bird species, 46 reptile species, 28 amphibian species, and 468 butterfly species, making it an ideal location for naturalist observations and educational activities.

2.2 Naturalist Training Camp

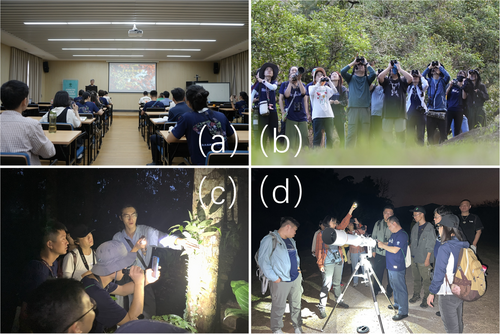

The Naturalist Training Camp is an educational program organized by the Environmental Education Center at XTBG. Held twice a year, the program selects approximately 30 participants from a nationwide applicant pool. The training lasts around 9 days and includes lectures and outdoor practical observation sessions (Figure 2), covering various natural subjects such as plants, insects, reptiles, arthropods, and birds. Renowned researchers and science communicators deliver lectures in each field with the goal of developing knowledgeable naturalists and creating a platform for enthusiasts to learn and engage. This study focused on the fourth and fifth sessions of the camp, which took place in March and September 2023, with 29 and 30 participants, respectively. Additional program details can be found in Appendix A.

2.3 Data Collection

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to collect and analyze data on the changes in participants' experiences before and after their involvement in the Fifth Naturalist Training Camp. The research followed a pilot study involving participants from the Fourth Naturalist Training Camp.

2.3.1 Pilot Study

The pilot study was conducted during the Fourth Naturalist Training Camp in March 2023 to validate the model framework and assess the reliability and validity of the study scales, including both content and structural validity. In August 2023, a questionnaire was distributed to all 29 participants from the fourth session, and interviews were conducted with 11 of these participants. The interview outline and scales used in the pilot study were the same as those in the formal study (see Sections 2.4 and 2.5). The interviews were conducted via WeChat voice calls and lasted between 13 and 36 min. These calls were recorded with all participants' consent.

To ensure the independence of the experimental results, participants from the fourth session of the Naturalist Training Camp were invited solely to participate in the pilot study and did not take part in the formal study. The results of the pilot study indicated that all scales demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity (Cronbach's α > 0.7), except the Social Connectedness Scale, which did not meet the required structural validity. In the structural validity assessment of the Social Connectedness Scale, the communality values for the items (translated from the original Chinese) “I found myself disconnected from society” and “I feel like a loner and a lonely person” were below the acceptable threshold (less than 0.4), leading to the removal of these two items. Following this deletion, the scale was reduced to 7 items, maintaining a single-dimensional structure with a Cronbach's α of 0.908.

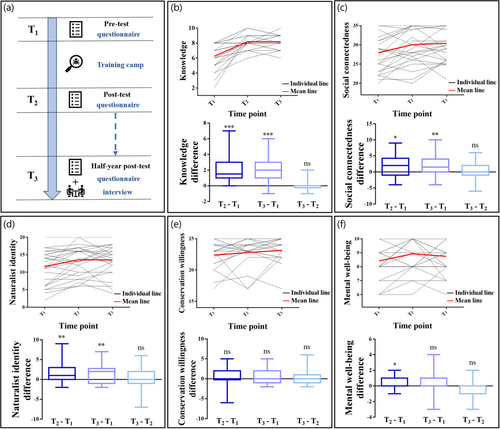

2.3.2 Study Procedure

The study included 30 participants from the fifth session of the Naturalist Training Camp in September 2023. At the beginning of the camp, participants completed a pre-test survey (T1) comprising 33 items, which took approximately 5 min to complete. The survey included scales measuring natural knowledge, social connectedness, naturalist identity, conservation willingness, and mental well-being, as well as demographic variables. At the end of the camp, participants completed a post-test survey (T2), which contained the same content as the pre-test, excluding demographic variables to avoid redundancy. In March 2024, 6 months after the camp, participants underwent a follow-up test (T3), with 16 participants also taking part in semi-structured interviews. The T3 test mirrored the content of T2. A total of 26 final samples were obtained (Table 1).

| Items | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 |

| Female | 16 |

| Age | |

| 20–30 | 12 |

| 31–40 | 7 |

| 41–50 | 4 |

| 51–60 | 3 |

| Education | |

| Middle school | 1 |

| High school | 2 |

| Undergraduate degree | 14 |

| Postgraduate degree | 9 |

| Income (RMB/month) | |

| 0–3000 | 5 |

| 3001–5000 | 3 |

| 5001–10,000 | 10 |

| 10,001–20,000 | 4 |

| > 20,000 | 4 |

Initially, all 30 participants completed the questionnaire assessment at T1. During the camp, three participants withdrew due to scheduling conflicts, resulting in 27 samples for the post-camp assessment at T2. With the exception of one participant who was unreachable, all 26 participants who completed T2 also completed the follow-up questionnaire at T3.

2.4 Scales and Questionnaires

- 1.

Knowledge Assessment: This section included ten questions designed by the training camp instructors to evaluate participants' comprehension of the course material. It featured five text-based questions and five image recognition questions, each with four multiple-choice options. For example, one question asked, “Which of the following animals is not an amphibian? A. Toad B. Turtle C. Newt D. Giant salamander.”

- 2.

Social Connectedness Scale: We utilized the Chinese revised version of the Social Connectedness Scale-Revised (SCS-R) developed by Lee et al. (2001) to assess participants' social connectedness. Given the limited availability of social connectedness scales in Chinese, we selected the SCS-R, which was translated into Chinese in 2022 and demonstrated good reliability among Chinese college students (Cronbach's α = 0.916, Wu et al. 2022). Two items were excluded from the pilot study to enhance the scale's structural validity. The revised 7-item scale exhibited a promising single-dimensional structure, with a Cronbach's α of 0.895.

- 3.

Naturalist Identity Scale: We adapted a simplified version of the naturalist identity test based on the Scientific Identity Scale (Hazari et al. 2010; Hosbein and Barbera 2020). This scale assessed participants' identity as naturalists and how they perceived their naturalist identity to be viewed by others.

- 4.

Conservation Willingness Scale: To enhance the relevance of the scale to our study participants and course interventions, we adapted a five-item scale from the study by Aiman et al. (2022) and Zelenika et al. (2018), employing a 5-point Likert scale. An example item included, “I am willing to sign a petition to protect tropical rainforests.” The scale demonstrated acceptable reliability, with a Cronbach's α of 0.867 in this study.

- 5.

Mental well-being Scale: Participants responded to a 4-item scale from the UK's Office for National Statistics (Office of National Statistics [ONS] 2011; White et al. 2017) with the question, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your current life?” Responses were rated on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). Previous research has validated this scale as a reliable measure of mental well-being among Chinese adult residents (Liu et al. 2022).

2.5 Interviews

The qualitative interview component was included to complement the quantitative analysis by providing explanatory insights into specific variables, such as enhancements in social connectedness, and to serve as an evaluation tool for assessing the effectiveness of the program. By incorporating qualitative interviews, we aimed to capture a more nuanced understanding of participants' experiences and the mechanisms underlying the observed changes, which may not be fully captured by quantitative measures alone.

A total of sixteen participants from the fifth session of the Naturalist Training Camp were interviewed using a semi-structured interview approach, employing convenient sampling. The interviews consisted of seven semi-structured questions, such as (1) What are your impressions of the camp? (2) What did you gain from the Naturalist Training Camp? (3) How has this camp experience impacted your work, life, and social interactions in the 6 months since the camp? The interviews were conducted online by WeChat voice call and lasted between 15 and 42 min. All interviews were recorded with the participants' consent.

2.6 Data Analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality of the data distribution. The results showed that all datasets deviated from a normal distribution; therefore, the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was used to analyze changes in paired data. Quantitative data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26), which included assessing scale reliability and validity, as well as conducting paired tests to compare pre- and post-experiment samples using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. Specifically, pairwise non-parametric tests were performed between time points T1, T2, and T3 to examine variations in each parameter across different time intervals. A post-hoc power analysis was also conducted to ascertain whether the study had sufficient power to detect significant changes.

Qualitative data were analyzed using MAXQDA (2022) with the content analysis method, which involves encoding, classifying, and quantifying textual data to identify patterns and themes (Krippendorff 2018). For the interview data, conversations were transcribed using iFlytek software, and the content was coded according to the framework presented in Figure 1. Both inductive and deductive approaches were employed to analyze participants' experiences: inductive analysis facilitated the identification of emergent themes related to the camp environment (e.g., novelty, family-like atmosphere, and professionalism), while deductive analysis assessed program effectiveness based on predefined themes, such as knowledge, social connectedness, naturalist identity, conservation willingness, and mental well-being. The coding criteria were derived from the results of the pilot study and relevant literature.

The coding process was carried out by two graduate students specializing in environmental education. They employed reflexivity and engaged in regular discussions to minimize potential bias and ensure consistency. This methodological combination allowed for a comprehensive understanding of both emergent and theory-driven aspects of participants' experiences. The primary and secondary coding indicators are presented in Section 3.2. For instance, the concept of naturalist identity is subdivided into self-identification and identification by others.

2.7 Research Ethics

This study adhered to the ethical guidelines set by XTBG and received ethical approval from the XTBG Biomedical Ethics Committee (Reference No: XTBG-2023-006). Before the study commenced, participants were provided with detailed information about the research objectives, methodologies, and potential benefits and risks, both through written and verbal communication. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. All participant identities were kept confidential and used solely for analytical purposes.

3 Results

3.1 Effectiveness of the Camp Based on Quantitative Data

Significant improvements were observed in knowledge (W = 253, p < 0.001), social connectedness (W = 147, p = 0.009), and naturalist identity (W = 169, p = 0.004) among the variables examined, and these changes were sustained 6 months later (Knowledge: W = 278, p < 0.001; Social connectedness: W = 155, p = 0.003; Naturalist identity: W = 195, p = 0.002, Figure 3). The camp had a marginally significant effect on mental well-being (W = 64, p = 0.024), although this effect was no longer significant at the 6-month follow-up (W = 32, p = 0.213). No significant difference in conservation willingness was observed between pre-test and post-test data (W = −45, p = 0.288). Notably, conservation willingness continued to increase after the camp, with the difference reaching a marginally significant level after 6 months (W = 98, p = 0.064, see Figure 3). The post-hoc power analysis showed a power of 0.688 for a medium effect size (d = 0.5) and 0.975 for a large effect size (d = 0.8).

3.2 Findings From Qualitative Data

3.2.1 Factors Contributing to the Effectiveness of the Camp

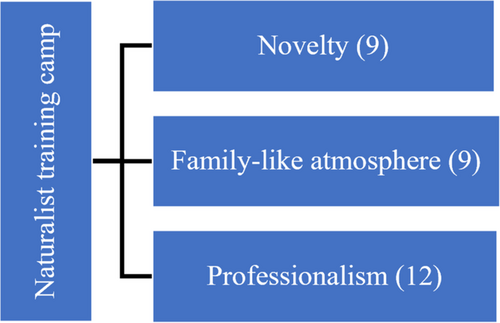

A thematic analysis of interview responses to the question “What are your overall impressions of the camp, and what stood out?” revealed three significant factors contributing to the camp's success: the novel environment, the family-like atmosphere, and the professionalism (Figure 4).

The novel environment highlighted by participants included the camp's distinctive location, the organization of activities, and the course content. The camp took place at XTBG, a tropical garden surrounded by rainforest, which was particularly refreshing and novel for many participants accustomed to temperate climates. One participant expressed astonishment at seeing some new plants, “One of the teaching assistants took us to see the jade vines in the botanical garden. It was my first time seeing green flowers, and I was honestly blown away.” (Participant 11). Various activities at the camp provided a sense of novelty and excitement, such as interacting with spiders, snakes, and other creatures. As Participant 3 expressed, “I had so many new experiences—like handling spiders, snakes, and lizards for the first time. I'd never dared to touch them before, and I thought it was really cool.” Additionally, the educational courses introduced participants to subjects beyond their prior knowledge, expanding their understanding of nature and providing a sense of discovery. For example, Participant 4 said, “I felt like the camp kept opening new worlds to me. For example, I was pretty familiar with plants before, so it was like my eyes were only tuned in to them. But after the instructors introduced things beyond plants, it felt like my senses had expanded, and I started noticing insects and all kinds of new things. I was like stepping into a whole new world.”

The family-like atmosphere refers to the supportive environment for participants, characterized by intensive interpersonal interactions and collaborative activities. As the camp is located in a relatively remote and secluded botanical garden, four teaching assistants were assigned to help participants quickly acclimate to the environment. Participants also experience this supportive interpersonal dynamic, as expressed by one participant: “The atmosphere at the camp was amazing. The instructors and teaching assistants were all really thoughtful and approachable—you could ask them for help with anything. When I first arrived, I was worried I wouldn't fit in, but I actually adjusted to the learning environment really quickly.” (Participant 1).

One of the objectives of the camp is to foster connections among participants, thus promoting cooperation and interaction through various small group projects. Many participants found this enhanced their learning experience. Participant 4 shared: “At the Naturalist Training Camp, I found a sense of belonging that I hadn't felt in a long time—just being with a group of people who all love nature. In such a beautiful place like the botanical garden, everyone was doing what they enjoyed. There was this amazing sense of inclusiveness because no matter our ages or professions, we were all happily observing and discussing nature together. It was a truly wonderful experience.”

Professionalism encompasses the depth and breadth of course knowledge, the expertise of instructors, and the practicality of the course content. The teaching team at the Naturalist Training Camp includes some of China's most renowned naturalists and researchers, whose contributions significantly enhance the professional quality of the courses. Participants have consistently praised the professionalism of the Naturalist Training Camp. One participant commented: “The instructors were really knowledgeable—top-notch professionals. The camp didn't just offer expert-led courses; you could actually feel their passion for nature. It made me want to be someone like them.” (Participant 7).

Naturalists exemplify a comprehensive understanding of natural knowledge, which is evident in the curriculum design. The extensive course content allows participants to develop a profound understanding of nature. Another participant noted: “The courses during the camp were really specialized and diverse, coving plants, insects, mosses, birds, and many other areas. The instructors were incredibly knowledgeable.” (Participant 11).

Since natural history is a hands-on activity, teachers not only impart knowledge but also teach participants skills and methods for understanding nature, which leave a lasting impression. For instance, Participant 14 said during the interview: “Teacher H took us into the botanical garden to observe plants in the field and taught us how to identify and classify them. I didn't remember many of the plant names, but I still remember the methods he taught us—they've been really practical.”

3.2.2 Course Education Effectiveness Evaluation

Knowledge: Fifteen participants reported significant improvements in their understanding of nature and their ability to identify species (Figure 5). For instance, participant 12 mentioned, “Honestly, I didn't know much about terrestrial shellfish before—I didn't even know that term existed. After learning about shellfish classification in class, I realized I didn't actually know the difference between semi-slugs, snails, and slugs. It turns out that most of the time, what I thought were snails were actually semi-slugs. It made the world feel so much clearer to me.”

In addition to knowledge about nature, participants frequently mentioned the importance of gaining skills to understand nature. As Participant 6 stated, “The camp taught us a classification system that helps us to identify species. We also learned how to use different identification tools. Before, when I came across something unfamiliar, I had no idea how to figure out what it was. But now, I can ask the instructors and my classmates from the camp, or I can use apps like iNaturalist—I've gotten pretty good at using it.”

Social Connectedness: The majority of participants (15) reported developing strong friendships during the camp, which they continued to maintain after the camp ended, leading to an expansion of their social networks. Participant 12 stated, “I made a lot of new friends at the Naturalist Training Camp, and we've stayed in touch since it ended. It felt really great to meet like-minded people. Some of the friends I made there have even helped me out since then. When I shared my camp experiences with my old friends, they also found it really interesting, and I felt like it brought us closer together too.” These friendships not only endured but also extended to other social interactions. Over half of the participants are involved in nature education, and there has been significant collaboration and knowledge exchange since camp. “I've kept in touch with the participants, instructors, and teaching assistants. Every time I visit the botanical garden, I ask the instructors for advice on our natural education. Many of us participants are active in the field of nature education, and there are also quite a few nature education organizations in Guangdong. Sometimes we meet in Guangdong and have even collaborated on some courses.” (Participant 5).

Naturalist Identity: Twelve of the 16 participants reported that their naturalist identity was strengthened by the camp. Some participants gained confidence in the field of natural history. For instance, Participant 8 mentioned, “The camp made me feel more professional and gave me the confidence to share nature-related knowledge. Before, I felt it was hard to truly understand certain concepts, and I didn't have the confidence to discuss them with others.”

Participants also noted that their peers began to perceive them more as naturalists following their participation in the camp, which was significant for their identity. Participant 1, for example, shared, “I attended the Naturalist Training Camp in September. By October, a teacher from a well-known elementary school in Ningbo found out that I had joined the camp and invited me to give a lecture at the school as a nature expert.” The camp implemented various strategies to enhance participants' sense of identity, extending beyond the course material to encompass the overall experience. For instance, each participant received a personalized T-shirt with the term “Naturalists” printed on it. As Participant 3 remarked, “In the 6 months after the camp, I'd wear the camp t-shirt to nature-related events. Since it had ‘Naturalists’ printed on it, I felt a personal connection to the identity—it was a way of embracing who I was becoming. Of course, I know that I still have a long way to go before I can call myself a true nature expert.”

Conservation Willingness: Nine participants reported an increased willingness to engage in conservation activities after the camp. Seven participants attributed this to the knowledge they gained about natural history. Participant 2 said, “The camp helped me learn about a wider range of biological groups. Even though I was already a nature expert before, I only focused on animals. After the camp, I gained a deeper understanding of plant conservation. For example, I used to completely ignore moss, but now when I see it, I make sure not to step on it like I used to.” Six participants noted that their increased social connectedness may have played a role in enhancing their willingness to engage in conservation efforts. Social learning with peers was seen as critical for fostering a conservation attitude. For example, Participant 9 mentioned, “During my time at the botanical garden, I noticed some classmates gently moving small insects off the path so they wouldn't get stepped on, and this had a big impact on me. Now, when I'm out with friends, and they see an insect and feel grossed out or want to kill it, I stop them. I feel like the camp changed the way I see all kinds of living things. One classmate said, ‘Humans aren't superior or above everything—we should take note of and respect all living beings.’ That really stuck with me.” Interestingly, contrary to our initial hypothesis, no participants mentioned that their enhanced natural identity contributed to their enhanced willingness to engage in conservation activities.

Mental Well-Being: Fifteen participants reported improvements in their mental well-being after attending the camp. Six participants attributed this improvement to the new knowledge they had gained. For instance, Participant 3 expressed, “The first time I walked into the tropical rainforest, I felt a bit overwhelmed and sad because I didn't recognize anything around me. But after attending the camp, even though I still don't recognize most of the things I see, I've learned how to figure them out, and I've actually identified some plants. That made me feel a lot better—like I've built a stronger connection with the forest and the land. I think that's what boosted my sense of happiness and confidence.” Six participants believed that their improved mental well-being was a result of the new social network they formed. Participant 15 shared, “My mental state improved a lot after coming back from the Naturalist Training Camp. Before the camp, I had severe anxiety—I rarely left home or talked to anyone. But at the camp, I could chat with like-minded people and take part in activities we were all passionate about, and it felt like a huge shift in my life. You know how adult socializing is often so practical and transactional—it's hard to find spaces that are purely based on shared interests. But the camp provided that kind of space. After it ended, my mental health got so much better, and staying in touch with the friends I made there has made me feel incredibly fulfilled.” Two participants noted that their strengthened naturalist identity gave them a sense of accomplishment and purpose, positively impacting their mental health. Participant 8 explained, “The friends I made at the camp were incredibly talented and knowledgeable, and I felt so inspired—I wanted to be as skilled as they are. I feel like I'm gradually becoming more professional. Now, I can confidently share the things I've learned with others, whereas before, I wouldn't have dared to speak up. The camp gave me a clear sense of direction for the future, and I often encourage people around me to appreciate nature. For instance, when my friends' kids have questions about nature, they often come to me for answers now, and that gives me a real sense of accomplishment and purpose.”

In conclusion, the qualitative data obtained from the interviews indicate how the camp influenced participants' willingness to engage in conservation efforts and their mental well-being, as depicted in Figure 5.

4 Discussion

This study examined the effectiveness of a naturalist training camp led by qualified experts and held in a biodiverse tropical garden. The findings indicate significant improvements in participants' willingness to engage in conservation efforts and their mental well-being as a result of attending the camp. Knowledge acquisition and enhanced social connectedness were found to play a role in mediating these positive changes. Participants identified the camp's novel environment, familial atmosphere, and the professionalism of the instructors as key factors contributing to its success. These results emphasize the value of promoting amateur naturalists as an effective strategy to address current societal challenges, such as biodiversity loss and mental health issues.

4.1 Important Perceptual Characteristics of the Camp

Participants identified three key factors—novelty, a family-like atmosphere, and professionalism—as influential in shaping their impressions of the camp. For the majority of participants, many of whom came from temperate zones and were new to Xishuangbanna, the plants and insects at XTBG were unfamiliar and novel. XTBG's long-term organic management practices provide a habitat for a diverse range of animals and insects, enhancing the participants' sense of discovery. Furthermore, XTBG's comprehensive recording and information system, which sometimes incorporates online search systems (e.g., https://image.cubg.cn/; https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/biodiversity-of-xtbg), made it easy for participants to obtain the scientific names of any organisms encountered during their stay. These factors contributed to a heightened sense of excitement throughout the camp and positioned XTBG as an ideal venue for training naturalists. A novel and stimulating environment, such as the one the participants experienced at XTBG, has been shown to evoke positive emotions, curiosity, and a greater interest in learning (Lin et al. 2013; Mitas and Bastiaansen 2018).

A supportive environment and professional instructors are also key elements of an effective learning experience. According to constructivist learning theory, students actively construct knowledge by engaging with their surroundings and peers (Zajda 2021). When students perceive the course and the environment positively, they are more inclined to fully engage in learning activities, which leads to better knowledge construction and improved learning outcomes (Fosnot 2005). Thus, in future educational initiatives, course developers are advised to incorporate three key characteristics—novelty, a family-like atmosphere, and professionalism—to optimize educational outcomes.

4.2 Conservation Willingness

As a conservation education program, the primary objective of the camp was to increase participants' willingness to engage in conservation efforts by deepening their understanding of biodiversity and fostering a sense of identity as naturalists. Quantitative data collected through pre- and post-camp questionnaires indicated no significant improvement in conservation willingness immediately after the camp; however, a marginally significant increase was observed 6 months later. In contrast, qualitative data obtained through participant interviews 6 months post-camp revealed a marked enhancement in conservation willingness, as evidenced by the frequency of mentions from nine out of the 16 participants. These improvements were largely attributed to the knowledge acquired and the expanded social connections formed during the camp (see Figure 5).

The potential relationship between knowledge and conservation behavior has been debated for decades (Kaiser and Fuhrer 2003; Frick et al. 2004; Colombo et al. 2023). A well-known quote from Baba Dioum, delivered at the General Assembly of the IUCN in New Delhi in 1968, states, “In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.” This quote underscores the importance of knowledge about biodiversity. However, recent research, particularly in the field of environmental psychology, has suggested that, among several key variables, knowledge alone may not be a significant predictor of behavior (Steg et al. 2015; Van Valkengoed and Steg 2019).

In this study, knowledge—as evidenced by interview data—encompasses not only awareness of plants and animals but also the methods of acquiring relevant information. Previous studies have shown that these changes can improve participants' self-efficacy and sense of agency, which, in turn, may influence their willingness to engage in conservation efforts (Ineson et al. 2013; Merenlender et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2021). This finding aligns with research by Merenlender et al who evaluated naturalist training programs in the United States and found that such programs increased participants' ecological knowledge, scientific skills, and perceived ability to solve environmental problems. These individuals continued to participate in various environmental activities as citizen scientists after completing the training (Merenlender et al. 2016).

Some participants attributed their increased willingness to engage in conservation efforts to the influence of their classmates and instructors during the course. Individuals' behaviors and intentions are often influenced by others in their social circles or communities—a concept known as social norms (Magill 1995; Nolan et al. 2008). The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that social norms are a significant factor in predicting individuals' behavioral intentions (Ajzen 1991). For instance, a survey of tourists showed that subjective norms regarding green events could predict tourists' intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviors (Wong et al. 2020).

Notably, qualitative evidence derived from participant interviews indicated that a majority of participants exhibited an increased willingness to engage in conservation activities. However, the quantitative analysis did not demonstrate significant changes. This discrepancy may be attributed to participants' already high levels of conservation inclination prior to attending the camp, which could have led to a ceiling effect in the quantitative study. Consequently, future research might benefit from targeting populations with less established conservation commitments, such as schoolchildren or individuals less involved in nature-based activities. Engaging such groups could offer clearer insights into the potential of educational interventions, like the Naturalist Training Camp, to foster new conservation behaviors rather than merely reinforcing pre-existing attitudes.

Additionally, the post-hoc power analysis indicated that with a medium effect size (d = 0.5, power = 0.688), small sample sizes may have limited the study's ability to detect moderate effects, thereby increasing the risk of a Type II error. However, when the effect size was adjusted to a higher power (d = 0.8, power = 0.978), it may be possible to detect substantial effects. This suggests that future studies should use larger sample sizes to mitigate the risk of Type II errors.

4.3 Mental Well-Being

One of the primary goals of the camp was to enhance participants' mental well-being through the establishment and maintenance of social networks formed during the program. Previous research has shown that spending time in nature and engaging in community activities can significantly improve mental health and reduce stress (Bratman et al. 2021; Sachs 2022). Quantitative data from this study indicated a significant increase in mental well-being immediately after the camp; however, this effect did not continue after 6 months. In contrast, qualitative interviews revealed a sustained improvement in well-being, even 6 months after the camp.

Mental well-being, a multifaceted psychological state that is receiving increasing attention, is largely influenced by the fulfillment of basic psychological needs, as outlined in self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci 2017). These needs, including autonomy, competence, and relatedness, play a crucial role in shaping mental well-being. In our study, participants reported that acquiring knowledge was one factor contributing to their improved well-being. As discussed above, this knowledge encompassed biodiversity information and the skills needed to seek out or acquire relevant information. This increase in knowledge boosted participants' perceived competence and self-efficacy, as noted by several of them. This increase in perceived competence, which in turn supports mental well-being, is also evidenced by numerous previous studies (Cantarero et al. 2021; Shao 2023).

Another reported factor contributing to improved well-being was the establishment and maintenance of social connectedness during the camp, which is tied to the psychological need for social relatedness. For example, Participant 5 mentioned, “At the Naturalist Training Camp, I made a lot of new friends who share my love for nature. It made me feel like I wasn't the only person with this passion, and that made me very happy.” Relatedness, a fundamental psychological need, plays a significant role in contemporary life by helping alleviate daily stress and anxiety (Ryan and Deci 2017; Lataster et al. 2022).

Two of the 16 participants mentioned that their enhanced perceived naturalist identity also contributed to their improved well-being. According to social identity theory, developing and strengthening an individual's social identity can foster a sense of belonging within a group and reduce feelings of loneliness, both of which are crucial for mental well-being (Smith and Silva 2011; Haslam et al. 2022). This improvement in relatedness may have contributed to participants' feelings of enhanced well-being.

While some studies have explored the development of naturalist identity, none have examined the impact of naturalist community identity on psychological well-being. Our findings suggest that training individuals to become naturalists may offer a promising approach to addressing global mental health challenges.

4.4 Limitations of the Study

Our findings suggest that the Naturalist Training Camp serves as an effective educational model for improving knowledge, social connectedness, identity, conservation willingness, and mental well-being. However, there are limitations that may affect the generalizability of the results. The relatively small sample size and geographical constraints may limit the broader applicability of our findings. Future studies should aim to increase both sample size and diversity in order to better evaluate the long-term effects of similar programs. Furthermore, the demographic characteristics of our participants revealed a predominance of well-educated adults, which highlights the need to include a more diverse population in future research, such as children and individuals with lower levels of education.

5 Conclusion

This study conducted a comprehensive assessment of the educational effectiveness of the Naturalist Training Camp held at XTBG. The evaluation focused on key perceptual aspects of the course and investigated its impact on participants' biodiversity knowledge, social connectedness, identity, conservation willingness, and mental well-being. The findings indicated that the camp's most significant features include novelty, a family-like atmosphere, and professionalism. Moreover, the camp was found to notably improve participants' willingness to engage in biodiversity conservation, strengthen their identity as naturalists, and enhance their mental well-being.

The resurgence of promoting amateur naturalists, a practice that originated in some developed countries a century ago, has gained momentum in China in the 21st century. This approach is seen as a new and promising strategy for advancing ecological civilization, with the core objective of improving the well-being of both nature and people.

Author Contributions

Yichuan Meng: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, writing–original draft. Jiangbo Zhao: project administration. Jin Chen: methodology, supervision, writing–review and editing.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences. We are grateful to the Environmental Education Center for its support of the research and to the participants of the 4th and 5th Naturalist Camp for their help in the data collection process. Finally, we would like to thank Naufal Avicena for his suggestions on the manuscript. The publication of the photos in Figure 2 in Integrative Conservation has been approved by the individuals photographed.

Ethics Statement

This study followed the ethical guidelines established by XTBG, and received ethical approval from the Biomedical Ethics Committee of XTBG (Reference No: XTBG-2023-006). All participants were informed of the research objectives, methodologies, potential benefits, and risks prior to the study and provided written consent. Participants were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. All data collected were kept confidential and used solely for the purposes of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.