Fostering Children's Self-Efficacy Through Nature Education: Insights From a Wildlife Education Program in Rural China

通过自然教育培养儿童的自我效能感:中国乡村自然课项目的启示

Editor-in-Chief: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Handling Editor: Yu Huang

ABSTRACT

enEmphasizing self-efficacy in nature education holds significant potential for achieving long-term conservation goals, such as fostering conservation support and engagement. However, the effect of nature education on children's self-efficacy is rarely evaluated, and there is a lack of clarity and evidence on how course design influences its development. Here, we evaluated the effect of nature education on children's course-developed self-efficacy using a mixed-methods design involving a wildlife-based education program implemented in 10 rural elementary schools across six provinces in China. Results indicated that the program significantly increased students' course-developed self-efficacy in learning about nature and personal development, as evidenced by a comparison between the “course” group (N = 403) and a “control” group (N = 132). Using linear mixed models, we found that course-developed self-efficacy also contributed to pro-nature intentions and behaviors, with self-efficacy being a more important predictor of the latter. Moreover, the qualitative data identified seven key pathways through which the course may enhance children's self-efficacy: positive reinforcement, teamwork, skill development, self-expression, role modeling, knowledge expansion, and a supportive atmosphere. We propose that self-efficacy is a crucial outcome of nature education and offer guidelines for maximizing its impact on future generations in rural China.

摘要

zh在自然教育中强调自我效能感对实现长期保护目标 (如提升保护支持或参与度) 具有重要潜力。然而, 自然教育对儿童自我效能感的影响鲜少被评估, 且课程设计如何影响自我效能感尚缺乏明确的证据。本研究采用混合方法设计, 通过在中国六个省份的10所乡村小学实施的野生动物相关自然课项目, 评估了自然教育对儿童课程相关自我效能感的影响。结果表明, 与对照组 (N = 132) 相比, 参与课程的学生 (N = 403) 在自然学习和个人发展方面的自我效能感显著提升。线性混合模型显示, 课程相关的自我效能感还促进了亲自然意愿和行为, 其中自我效能感对后者的预测作用更强。质性分析进一步揭示了课程提升儿童自我效能感的七种关键路径:积极强化、团队合作、技能培养、自我表达、榜样示范、知识扩展和支持性氛围。我们认为, 自我效能感是自然教育的重要成果, 并提出了在乡村中国最大化其影响的指导建议。

简明语言摘要

zh通过自然教育教导儿童相信自己的能力 (自我效能感), 有助于实现长期的保护目标, 例如鼓励人们保护自然。然而, 目前很少有研究验证自然教育如何影响儿童的自信心, 或课程设计如何影响这一过程。我们评估了在中国六个省份的10所农村小学开展的一项野生动物相关的自然课项目。问卷调查和访谈表明, 参与课程的学生 (403名儿童) 比未参与的对照组 (132名儿童) 在自然学习和个人成长方面有了更大的自信提升。这种自信还促使他们更积极地采取保护自然的行动。我们发现课程通过七种关键方式增强信心:积极反馈、团队合作、实践技能、自我表达机会、榜样示范、知识扩展以及支持性的课堂氛围。研究结果强调, 培养自我效能感应成为自然教育的核心目标。我们建议在课程设计中融入这些要素, 帮助中国乡村乃至全球的儿童增强保护自然的能力。

Summary

enTeaching children to believe in their abilities (self-efficacy) through nature education can help achieve long-term conservation goals, such as encouraging people to protect nature. However, few studies have tested how nature education affects children's confidence or how course design supports this. We studied a wildlife education program in 10 rural elementary schools across six provinces in China. Surveys and interviews showed that students who took the course (403 children) gained more confidence in learning about nature and personal growth compared to those who did not (132 children). This confidence also led to stronger intentions and actions to protect nature. We found seven key pathways through which the course helped build confidence: positive feedback, group work, hands-on skills, opportunities to express themselves, role models, learning new knowledge, and a supportive classroom environment. Our results highlight that building self-efficacy is a vital goal for nature education. We recommend designing courses with these elements to help children in rural China—and beyond—feel empowered to protect the natural world.

-

Practitioner Points

- ∘

Prioritize children's self-efficacy as a key outcome in nature education programs to empower their long-term conservation engagement and personal development.

- ∘

Incorporate experiential learning strategies, such as hands-on tasks, collaborative projects, and relatable role models, to reinforce students' confidence and practical skills.

- ∘

Cultivate inclusive, supportive environments through positive reinforcement and equitable participation, reducing barriers to self-efficacy development in diverse learner groups.

- ∘

实践者要点

zh

-

将提升儿童的自我效能感作为自然教育项目的核心成果, 以增强他们在长期保护参与和个人发展中的能力。

-

融入体验式学习策略 (如动手实践任务、团队合作、互动榜样角色), 巩固学生的信心与实践技能。

-

营造包容与支持性的环境, 通过积极反馈和公平参与, 降低不同学习者群体发展自我效能感的障碍。

1 Introduction

The global challenge of biodiversity loss demands an urgent response to enhance public understanding and engagement in conservation efforts (Sutherland et al. 2020). This goal is central to many conservation strategies, particularly those that focus on nature education as a means to promote biodiversity conservation (Børresen et al. 2023). A critical factor influencing participation in conservation activities is individuals' self-efficacy, which has gained attention in various educational interventions (Gong et al. 2021; Bruyere et al. 2022). Self-efficacy, defined as an individual's belief in their capability to perform specific behaviors, significantly impacts their attitudes and responses to various situations (Bandura 1977, 2001). In educational contexts, self-efficacy affects levels of motivation and attitude, learning performance, and the choice of activities and careers (Schunk 1995; Pajares 1996; Schunk and Pajares 2002). For example, students with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage actively, exert greater effort, persist in the face of challenges, and experience fewer negative emotional reactions compared to those who doubt their abilities (Bandura 1997; Zimmerman 2000).

Emerging from social cognitive theory, self-efficacy has been identified by a growing body of recent research as one of the most important factors influencing various pro-nature objectives, such as conservation behaviors related to natural resources (Pradhananga and Davenport 2022; Savari, Naghibeiranvand, et al. 2022; Savari, Yazdanpanah, et al. 2022), climate change mitigation (Qin et al. 2024; Vrselja et al. 2024), conservation diffusion behavior (Champine et al. 2022; Jones and Niemiec 2020), and support for biodiversity protection (Bruyere et al. 2022; Dörge et al. 2022; Puri et al. 2024). Consequently, an increasing number of studies in the field of ecological conservation are exploring the role of self-efficacy in promoting effective conservation actions.

Emphasizing self-efficacy in nature education holds great potential, as it is essential in linking educational programming to some of the most important long-term objectives in conservation and broader life goals. Firstly, the challenges of conservation often require sustained effort and persistence. Unlike other pro-environmental activities that can be practiced daily, some conservation experiences and skills may take years to acquire and hone, necessitating motivation and long-term commitment to maintain engagement (Smith et al. 2022). Promoting self-efficacy can also influence an individual's likelihood of applying new skills and knowledge in real-life situations, which is a key desired outcome of many nature-related educational programs (Bruyere et al. 2022). By addressing noncognitive factors such as self-efficacy, nature education could go beyond conveying knowledge and skills for conservation to empower individuals to apply their learning in both conservation practices and various life pursuits (Bruyere et al. 2022). However, despite the significance of self-efficacy in life beyond school, the impact of nature education programs on this critical outcome is rarely evaluated.

In contrast to training programs focused on improving specific skills or behaviors related to conservation, nature education programs for children typically do not prioritize environmental behavior change as their primary objective. Instead, nature education encompasses a broader spectrum of goals that are more general in nature and not necessarily linked to specific conservation behaviors. These courses may be designed to integrate various combinations of knowledge and skills pertinent to both conservation and personal development. Such an approach can foster a wider range of outcomes by cultivating more generalized forms of course-developed self-efficacy, rather than merely offering technical solutions to specific issues (Hamilton et al. 2022). Moreover, even when educational programs provide knowledge and skills that facilitate relatively straightforward course performance, increased self-efficacy may produce a spillover effect, enhancing students' willingness to engage in more challenging conservation behaviors (Lauren et al. 2016). We propose that course-developed self-efficacy serves as an important mediator in building competencies that translate into future pro-nature and conservation behaviors. Therefore, we also intend to examine the relationship between course-developed self-efficacy and pro-nature intentions and behaviors.

Another key aspect is to study the underlying mechanisms by which students' self-efficacy can be enhanced through nature education programs. Multiple studies have identified four primary sources from which self-efficacy is derived: (1) performance accomplishments from personal experiences; (2) vicarious experiences gained by observing others perform an activity; (3) verbal persuasion from others; and (4) physiological and affective states, whereby anxiety, stress, or other emotional states affect the judgment of efficacy (Bandura 1977). Existing research has used such theories to provide insights and suggestions on how to improve self-efficacy through various activities and training programs, such as citizen science projects (Lynch et al. 2018). However, much focus has been placed on participants' performance or teacher-student relationships, rather than on the specific design of the course itself. Meanwhile, nature education programs often lack clarity and empirical evidence regarding how course design influences students and facilitates desired outcomes (Sawrey et al. 2019). Therefore, gaining a better understanding of course design effects is essential for informing future nature education program design aimed at enhancing student's self-efficacy.

In our study, we propose that course-developed self-efficacy is a crucial outcome of nature education, with the potential to enhance pro-nature and conservation behaviors. We evaluated the impact of a wildlife-based education program on the course-developed self-efficacy of children in schools in rural China, guided by three research questions: (1) Can nature education improve children's self-efficacy? (2) Can the improvements in course-developed self-efficacy lead to pro-nature intentions and behaviors? (3) What pathways link the design of nature education courses to improvements in children's self-efficacy? By emphasizing self-efficacy in nature education and analyzing its underlying mechanisms, we discuss how nature education can broaden its impact in a rapidly changing world, particularly for rural generations growing up in the Anthropocene.

2 Methods

2.1 Wildlife-Based Nature Education Program

We used a nature education program called “The Wildlife Course in the Classroom: My Wildlife Friends” (hereafter referred to as the Wildlife Course), developed and implemented by the One Planet Foundation. Aimed at primary school students aged 8–10, the core objectives of the Wildlife Course are to stimulate students' curiosity and interest in nature, deepen their concern for wildlife, build an understanding of natural ecosystems, and encourage proactive engagement in pro-nature behaviors.

Spanning one semester (approximately 4 months), the course is primarily delivered through 16 video lessons (as detailed in Table S1). These video lessons use rich multimedia to introduce a diverse array of China's native wildlife, including endangered species such as the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), the Yangtze finless porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis), and the snow leopard (Panthera uncia). Through immersive scenarios and project-based learning techniques, the videos allow students to explore the natural world, observe wildlife, and simultaneously acquire curriculum knowledge while learning broader life concepts. Students also interact with animated characters representing conservationists, scientists, and rangers, who serve as role models. Additionally, “Qiuqiu (球球),” a cartoon character the same age as the students, accompanies them throughout the course journey. Each Wildlife Course lesson also features a hands-on interactive session, with each student being provided a material kit designed for practical activities. During this session, students engage in individual or group tasks related to the lesson topics, such as constructing a mini-habitat model box or writing a wildlife-themed story script—applying the knowledge gained from the lesson in a creative or participatory way.

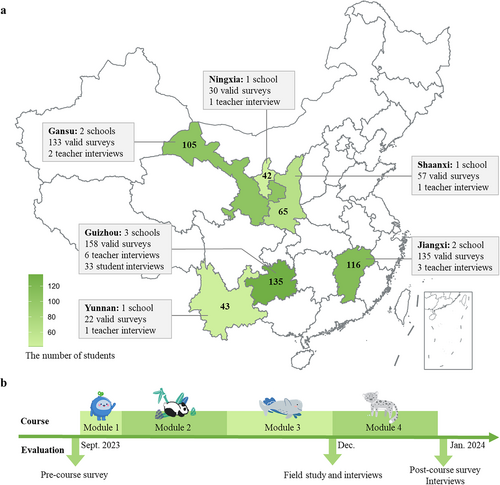

From September 2023 to February 2024, the Wildlife Course program was implemented in 10 rural primary schools across six provinces in China: Gansu, Guizhou, Jiangxi, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Shaanxi, and Yunnan (Figure 1). More than 500 students participated in the course for the entire semester. While local teachers used standardized video lessons to deliver the course, they were encouraged to incorporate their own teaching styles and integrate local resources.

2.2 Evaluation Design

This study employed a mixed-methods design to evaluate the effects of the Wildlife Course on the nature education outcomes of participating students. First, an evaluation survey was designed and implemented before and after the course, with Likert scale questions embedded in the questionnaire to measure various outcomes. Additionally, teachers and students were interviewed, and students were asked to write letters, to identify potential outcome dimensions that may have been overlooked and to explore the mechanisms through which the course produced its effects.

2.3 Quantitative Survey Design

The survey questionnaire was designed to measure the impact of the Wildlife Course on students across multiple environmental outcome dimensions, including course-developed self-efficacy, pro-nature intentions, pro-nature behaviors, concept of life, and nature connectedness (Table S2). For the course-developed self-efficacy dimension (Cronbach's α: 0.82 in the pre-test, 0.85 in the posttest), the questionnaire included six items that addressed students' confidence in the knowledge and skills acquired from the Wildlife Course. These items encompassed students' knowledge about wildlife in China, hands-on skills, and their ability to share ideas and ask questions about wildlife (Table S3). Another item focused on student's belief in their ability to apply methods learned from the course to explore nearby nature. Students were asked to rate their confidence on a scale of 1 to 10 regarding the perceived self-efficacy they developed during the Wildlife Course.

Students' pro-nature levels were divided into two dimensions: pro-nature intentions and pro-nature behaviors, referring to actions that contribute to the sustainability of nature, including biodiversity conservation. Pro-nature intentions were measured using five Likert scale questions (Cronbach's α: 0.71 in the pre-test, 0.77 in the posttest). In addition, students' pro-nature behaviors were measured through five questions (Cronbach's α: 0.67 in both pre-test and posttest), each assessing the frequency of behavior during the last or current semester. Demographic information, such as gender and age, was also collected. The survey questionnaire spanned two pages, with an estimated completion time of 15 to 20 min.

The questionnaire, developed based on a pre-and-post survey design, was administered to students in grades 2–5 participating in the Wildlife Course program in 10 rural elementary schools. In addition to classes with students who attended the Wildlife Course (the course group), some classes from the same schools and grade levels were selected as a control group consisting of students who did not participate in the course. Both groups completed the pre- and post-surveys simultaneously. Program schools were free to decide whether or not to include a control group for evaluation, resulting in the control group sample not representing all program schools. Following questionnaire collection, data cleaning and reliability testing for the Likert scales were performed to ensure data quality (Tables S2 and S3).

2.4 Qualitative Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with teachers and students to gain a comprehensive understanding of the program's impact from diverse perspectives. The interviews began with general questions about participants' impressions of the Wildlife Course and gradually delved into various potential outcome dimensions, including perceived changes in course-developed self-efficacy and pro-nature behaviors resulting from course participation. Specific cases of change were explored through follow-up questions to uncover the mechanisms behind the course's effects.

All student interviews were conducted during field visits to three program schools in Kaili City, Guizhou Province, toward the end of each Wildlife Course. A total of 11 groups of students (36 individuals in total) were interviewed. Each student group interview lasted approximately 15 min, totaling 165 min of recorded material. Interviews with six local teachers were also conducted during the field visits, while the other eight teachers were interviewed online after the course. Each one-on-one teacher interview lasted approximately 30 min, resulting in a total of 420 min of interview recordings.

Interviews were recorded, and verbatim transcripts were generated using “Tencent Meeting,” a meeting software platform. Teacher interviews were labeled T1–T14, and student group interviews S1–S11. After the course, students were also invited to write a letter to the animated character Qiuqiu to express their feelings about the course in response to a letter from Qiuqiu (Figure S1).

2.5 Data Analysis

2.5.1 Statistical Tests

Two statistical methods were used to evaluate the nature education outcomes of the Wildlife Course. First, we assessed whether there were significant changes in outcome measurements before and after the course by conducting paired-sample Wilcoxon tests on matched data for both the course and control groups. Additionally, to determine whether the changes in outcome variables differed between the two groups, we calculated average change scores by subtracting pre-test scores from posttest scores and compared these scores between the course and control groups using a two-sample Wilcoxon test. All analyses were performed with R statistical software version 4.3.1.

2.5.2 Linear Mixed Models

We conducted a robust evaluation of the relationship between changes in self-efficacy and other variables and changes in students' pro-nature levels before and after the Wildlife Course, while accounting for demographic variables. Linear mixed models (LMMs) were constructed using the “lmer” function in the package “lmerTest.” The first model predicted changes in students' pro-nature intentions, while the second model predicted changes in pro-nature behaviors. Fixed effects of the models included changes in core educational outcomes, including self-efficacy, concept of life and nature connectedness, as well as students' age and gender. We also included changes in pro-nature intentions as a fixed effect for predicting pro-nature behaviors. School was treated as a random effect in both models to account for its influence on the course's impact.

We further conducted hierarchical multiple regression models to evaluate the effects of the course (Tables S4 and S5). A correlation matrix and variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated to evaluate multicollinearity. For our specified models, a uniform distribution of the scaled residuals was observed, and no significant deviation from uniformity in the y-direction was detected (Figure S2).

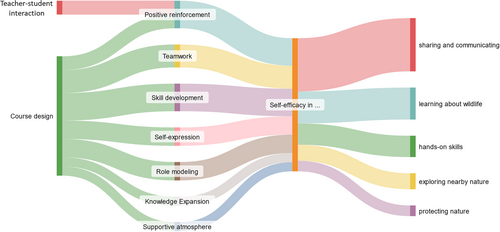

2.5.3 Thematic Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis using data from interviews and students' letters to Qiuqiu to identify pathways through which the Wildlife Course led to changes in students' self-efficacy. Thematic analysis is a systematic method for identifying, organizing, and interpreting patterns or themes within a data set (Braun and Clarke 2006). This approach allowed us to uncover commonalities in the course's impact on self-efficacy and provided a deeper understanding of the shared themes. Following Braun and Clarke's framework, we conducted the thematic analysis through the following steps: (1) familiarization with the data, during which we meticulously read and reviewed the verbatim transcripts to ensure the data could be categorized appropriately; (2) structural coding, in which broad statements related to students' self-efficacy and other nature education outcomes were labeled; (3) focused coding of features relevant to mechanisms of self-efficacy improvement—for example, how the role modeling by animated characters in the course design influenced students' self-efficacy; (4) searching for themes, where codes were grouped into potential themes and all relevant data were gathered for each theme. For instance, if multiple codes referenced how teamwork (a course design element) impacted students' self-efficacy, these were grouped under a theme related to teamwork and self-efficacy enhancement; (5) reviewing the themes, during which we checked the themes against coded extracts to ensure internal coherence, resulting in a thematic map of the entire data set; (6) defining and naming themes. Finally, we quantified each theme and illustrated the relationship between themes using a Sankey diagram (Figure 3). This visual representation provides an overview of how different pathways, originating from various course design elements, contributed to the enhancement of different aspects of students' self-efficacy.

3 Results

3.1 Sample Size

The sample size for the questionnaire survey included 535 students from 10 program schools, comprising 403 students in the course group and 132 in the control group. Additionally, interviews were conducted with 11 groups of students (totaling 36 individuals) from three program schools, as well as with 14 teachers from 10 program schools. Furthermore, a total of 272 students' letters to Qiuqiu were collected from 9 schools.

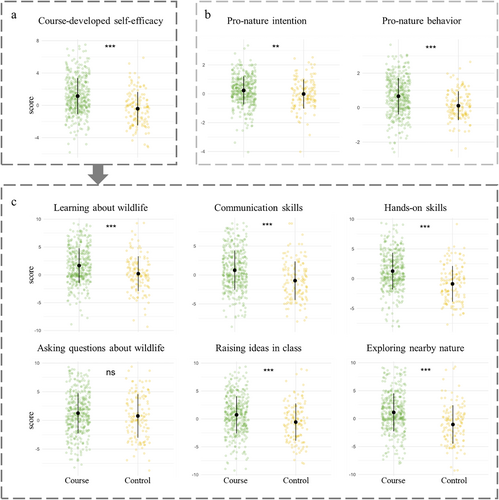

3.2 Education Outcomes: Improvement of Course-Developed Self-Efficacy

Comparisons of changes before and after the Wildlife Course demonstrated that the program significantly increased students' course-developed self-efficacy in a variety of areas, including learning about nature and personal development (p < 0.001). In contrast, self-efficacy dimensions among students in the control group significantly decreased after one semester (p = 0.011). The average changes in self-efficacy, as well as the changes in specific items, were significantly greater for the students in the course group compared to the control group, with the exception of the item regarding “being able to ask different questions about the behavior of a certain animal” (Figure 2a,c). In addition, students in the course group showed a significantly higher increase in pro-nature intentions and behaviors than those in the control group (Figure 2b).

3.3 The Effect of Self-Efficacy on Pro-Nature Intentions and Behaviors

Further analysis of the effect of course-developed self-efficacy on students' pro-nature levels revealed that self-efficacy was a significant influence on both pro-nature intentions and pro-nature behaviors. The LMM for predicting students' pro-nature intentions showed that self-efficacy was a significant factor in predicting changes in these intentions (p < 0.001) (Table 1). Additionally, the concept of life and nature connectedness was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001), showing that students with a better understanding of the concept of life and who felt closer to nature had higher intentions to protect nature (Table 1). The full model, after accounting for students' age, gender, and school affiliation, explained 41.1% of the variation in pro-nature intentions.

| Pro-nature intentions | Pro-nature behaviors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects Variables | b | p-value | b | p-value | ||

| (Intercept) | −0.02 | 0.86 | 0.01 | 0.92 | ||

| Age | −0.05 | 0.40 | −0.14 | 0.03* | ||

| Gender (ref. male) | 0.06 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 0.93 | ||

| Concept of life | 0.17 | < 0.001*** | 0.00 | 0.96 | ||

| Nature connectedness 1 | 0.32 | < 0.001*** | 0.18 | < 0.01** | ||

| Nature connectedness 2 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.08† | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.18 | < 0.001*** | 0.25 | < 0.001*** | ||

| Pro-nature intentions | / | / | 0.05 | 0.39 | ||

| Random effects Group | Variance | Std. Dev. | Variance | Std. Dev. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.41 | ||

| Residual | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.84 | ||

| Conditional R2 | 0.41 | 0.35 | ||||

- Note: Significance codes: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, †p < 0.1.

In terms of students' pro-nature behaviors, the LMM revealed that both course-developed self-efficacy and nature connectedness remained statistically significant predictors, with more self-efficacious students reporting higher frequencies of environmentally friendly behaviors (Table 1). Conversely, pro-nature intentions did not demonstrate a significant influence within the model. The full model accounted for 34.7% of the variance in pro-nature behaviors. The QQ-uniform plot for both models showed no significant deviations from the overall uniformity of the residuals (Figure S2). The simulated residuals did not differ from the observed residuals, indicating a good model fit (Figure S2).

3.4 Pathways: From Course Design to Self-Efficacy

The thematic analysis identified seven major pathways through which the Wildlife Course could enhance students' self-efficacy, based on synthesized qualitative data from in-depth interviews with teachers and students, as well as letters to Qiuqiu. The major pathways include positive reinforcement, teamwork, skill development, self-expression, role modeling, knowledge expansion, and a supportive atmosphere (Figure 3). Collectively, these pathways may contribute to the enhancement of students' self-efficacy, likely driven by both the design of the Wildlife Course and the interactions between teachers and students. Additionally, these mechanisms were influenced by students' sociodemographic characteristics, as well as regional and class-related factors.

Among the identified pathways, the theme of positive reinforcement (pathway 1) emerged from six teacher interviews, emphasizing the importance of positive feedback and verbal encouragement regarding students' performance, such as when answering questions. The video design of the Wildlife Course incorporated frequent verbal praise delivered by virtual characters, including Qiuqiu and scientists. The frequency and timeliness of verbal feedback from these characters and teachers are closely linked to students' perceptions of their personal efficacy. This, in turn, has encouraged teachers to incorporate this technique into their own teaching. “I was constantly trying to encourage my students to express themselves during the Wildlife Course. I found that if you give students a stage, they will respond with remarkable expressions, which further inspires me to believe in my students’ abilities” (T4). These positive interactions might have contributed to the cultivation of a supportive classroom atmosphere (pathway 7), as evidenced by two teacher interviews. The supportive atmosphere may be able to foster the emotional states necessary for enhancing self-efficacy. “The children in this class were extremely timid at first, presumably because previous teachers had been rather strict. However, in the relaxed and pleasant atmosphere of the Wildlife Course, their natural instincts were set free. With smiles beaming on their faces, they could confidently present their works for me to take photos” (T5).

The interconnected themes of teamwork (pathway 2) and skill development (pathway 3) emerged from nine teacher interviews, one student interview, and one letter to Qiuqiu. Several cases suggested how students gained confidence by collaborating as a team to complete practical tasks, which were deliberately incorporated into the course design. “There was a student with low self-esteem… However, when engaged in the group task of creating a mini-habitat box for pandas, the bamboo elements he crafted were remarkably well-made. In the team, he extended his help to his peers, assisting them in tasks such as crafting stone features. It seems that through this group-collaborative experience, he was able to discover his own worth” (T5). Students may have recognized their individual contributions during teamwork, also reflected in statements like, “…they discovered strengths within themselves; some were suited for leadership, while others excelled in hands-on tasks, working together to accomplish their goals” (T4). Notably, the improvement of self-efficacy requires a gradual process, where smaller hands-on tasks lead to larger accomplishments. Through progressive practice, as T3 noted, “not only did the students improve their crafting skills, but from being anxious and fearful at the beginning, they gradually learned to cooperate and found the experience enjoyable, becoming more willing to participate.”

The theme of self-expression (pathway 4) emerged from interviews with four teachers. They highlighted that the Wildlife Course was rich in opportunities for students to express themselves freely. “Expressing themselves on stage became their favorite part of the class, since they gained confidence through practice” (T3). Some teachers pointed out that, apart from the increased expressive skills, the growing confidence has transferred to students' performance in other subjects. “During the Wildlife Course, I asked questions more often, and the students eagerly raised their hands, more willing to express themselves than before. As their confidence grew, I noticed that students were even more willing to express their thoughts in my Chinese class” (T2). Moreover, the handicrafts created by students during the interactive, hands-on sessions of the course are presentable. Once completed, students can take them home to share with friends and family, which may further enrich their opportunities for self-expression. “After class, they couldn't wait to show off the forest badges they had crafted to students from other classes” (T3). T1 also noted, “Students are eager to take the finished works home and share them with their parents.”

A distinctive feature of the Wildlife Course is the cartoon character Qiuqiu, who serves as both a friend and a role model for the students (pathway 5). In four letters to Qiuqiu, students expressed their appreciation for the character's influence, stating, “I've been your friend since the first lesson” and “You not only provided us with a wealth of knowledge about wildlife but also guided us in overcoming many challenges.” Additionally, two teachers suggested the significance of knowledge expansion (pathway 6) in enhancing self-efficacy, especially for children in rural areas. “Our rural students often have limited exposure, but through the course, they gain insights into the broader and richer knowledge of the outside world, which boosts their self-confidence and has a lifelong impact” (T3). Finally, one teacher emphasized the equitable environment likely fostered by the Wildlife Course, stating, “I believe this course isn't just for the highest achievers; it is inclusive for everyone. Whether students are top performers, average, or struggling, they're all treated equally in this class. Unlike other subjects that create distinctions among students, here everyone is on the same level, eliminating any notions of good or bad” (T2).

Furthermore, the self-efficacy developed during the course may span across multiple dimensions, which can be summarized into five major themes: sharing and communicating, interest in active learning, hands-on skills, exploring nearby nature, and protecting nature (Figure 3). The theme of sharing and communicating emerged from ten teacher interviews, suggesting that students may have an increased eagerness to share and express their ideas, presenting confidently in front of the entire class. The theme of interest in active learning, derived from six interviews, seems to indicate that enhanced self-efficacy not only boosted students' motivation to engage with the course content but also positively influenced their confidence in learning across other subjects, such as science. The theme of hands-on skills originated from two student interviews and two letters to Qiuqiu, where students expressed their ability to overcome obstacles and reported greater self-efficacy in completing hands-on tasks within the course. The theme of exploring nearby nature was highlighted in two letters to Qiuqiu and one teacher interview, suggesting that students may be able to apply the skills learned in the Wildlife Course to observe local wildlife with greater confidence. Finally, the theme of protecting nature stemmed from one teacher interview and one letter to Qiuqiu, where students exhibited increased confidence and determination to take action in conservation.

4 Discussion

Our study identifies self-efficacy as a critical outcome of nature education, highlighting its potential to support long-term conservation goals, such as fostering conservation support or engagement. Using a mixed-methods approach, we assessed the effect of the course on children's self-efficacy. The results show a significant increase in course-developed self-efficacy among students of the course group, whereas the control group experienced a decline. This suggests that the program effectively boosted students' confidence in understanding biodiversity and life concepts, as demonstrated by their improved ability to ask insightful questions about animal behavior, creatively solve problems, and apply knowledge in natural contexts (Gong et al. 2021; Pirchio et al. 2021). Notably, this increase in self-efficacy pertains not only to students' confidence in performing pro-nature behaviors but also extends to their overall personal development across diverse course-related tasks. Additionally, we found that self-efficacy developed through the course also contributed to pro-nature intentions and behaviors, with self-efficacy being a more important predictor for the latter. This is crucial, as self-efficacy can drive long-term engagement in pro-nature behaviors, making it an essential target for nature education programs. Furthermore, we identified seven key pathways through which the course enhanced students' self-efficacy: positive reinforcement, teamwork, skill development, self-expression, role modeling, knowledge expansion, and a supportive atmosphere. These insights are essential for designing educational interventions aimed at achieving specific conservation outcomes.

The increase in self-efficacy observed among students in the course group enhanced their confidence in course-related tasks and significantly elevated their pro-nature intentions and behaviors compared to the control group. This aligns with previous studies that have identified self-efficacy as a key predictor of conservation behaviors (Wu and Mweemba 2010; Pradhananga and Davenport 2022; Ison et al. 2024). These findings suggest that fostering self-efficacy through nature education can extend beyond immediate course outcomes, motivating sustained engagement in biodiversity conservation efforts (Hamilton et al. 2022). It is noteworthy that the above-mentioned effects were obtained after controlling for demographical variables, and only age appeared to have an impact on pro-nature behaviors. Furthermore, the results underscore the importance of incorporating strategies into nature education that build self-efficacy to achieve a wide range of long-term outcomes (Smith et al. 2022). While self-efficacy may be more challenging to measure than tangible skills, there are meaningful ways to assess these less concrete attributes.

By understanding whether and how nature education contributes to bolstering self-efficacy, teachers and course designers can develop more effective programs tailored to support students. The thematic analysis of our study identified seven key mechanisms through which the course may improve self-efficacy. These pathways reflect the multifaceted nature of course design and the resulting teacher-student interactions, which collectively may foster a supportive and enriching learning environment. These mechanisms align with Bandura (1977) four primary sources of self-efficacy within his social cognitive theory: (1) enactive experiences (e.g., mastery, resiliency); (2) vicarious experience (e.g., social models of success); (3) social persuasion (e.g., reinforcement of positive self-image and reduction of self-doubt); and (4) emotional and physical states. This framework offers valuable insights for designing nature education programs that effectively foster self-efficacy.

Specifically, the presence of hands-on activities (pathway 3), collaborative tasks (pathway 2), and opportunities for expressing (pathway 4) may have been instrumental in building students' confidence and abilities, aligning with the enactive experiences outlined by Bandura. Nature education programs that incorporate simple, conservation-related tasks are useful strategies to provide experiential learning that contributes to children's self-efficacy (Hamilton et al. 2022). In the Wildlife Course, tasks like constructing a mini-habitat box for pandas in groups (Pathways 2 and 3) may allow students to engage directly, gain practical skills, and build confidence. Through such hands-on experiences, they not only learned about animal habitats but also realized their own capabilities. Similarly, project-based learning and situational course design (e.g., working on projects related to wildlife research) may offer students the chance to engage in real-world conservation and research processes, further reinforcing their self-efficacy (Kricsfalusy et al. 2018). Therefore, future nature education programs should prioritize knowledge acquisition and also the integration of diverse, interactive elements in their design. Highlighting successful role models (pathway 5) could also effectively enhance self-efficacy, though the impact of such vicarious experiences may vary depending on the characteristics of the model (Pradhananga and Davenport 2022). Notably, the design of Qiuqiu as an animated character in the Wildlife Course may be useful and serves as a successful example of an “aspirations window,” where relatable role models inspire students (Ray 2006). Therefore, course design could consider providing relevant success stories, conveyed by characters or individuals who resonate closely with students' own experiences, to maximize self-efficacy enhancement effects.

The pathway of positive reinforcement (pathway 1) aligns with social persuasion, emphasizing the pivotal role of feedback in fostering self-efficacy (Perry and Davenport 2020). Many teachers in our interviews noted that they provided more encouragement to students in the Wildlife Course compared to other subjects, suggesting that nature education programs may benefit from an intentional emphasis on positive reinforcement. This approach not only motivates students but also contributes to creating a relaxed and supportive learning environment (Pathway 7), which, in turn, might enhance the emotional states that support self-efficacy development. Moreover, nature education should strive to foster an equitable environment that values the personal growth of each student, regardless of traditional academic performance. By promoting inclusivity and reducing academic hierarchies, these programs may be able to engage a more diverse student body, ensuring that self-efficacy is nurtured across a broader spectrum of learners. Ultimately, by integrating positive feedback and creating supportive atmospheres, nature education programs may more effectively contribute to the long-term personal and behavioral development of students.

Our study also showed that the mixed-methods approach was invaluable for providing a comprehensive analysis and enhancing the interpretation of available survey data (Lynch et al. 2018). In particular, this approach uncovered unique, context-specific impacts on participants that would have been missed by surveys alone. The combination of quantitative and qualitative data underscores the value of mixed-methods research in capturing the full breadth of educational outcomes. However, there are several limitations to our study. First, we did not directly measure students' self-efficacy in conservation, in part because this outcome was not a major goal of the Wildlife Course during its course design stage. Additionally, the posttest survey was administered immediately after the course, and since the course lasted only one semester, it may not have been a sufficient indicator of changes in conservation behaviors. Longitudinal follow-up surveys are needed to assess the lasting impact of the program. Regarding the mechanisms of self-efficacy improvement, while the qualitative approach helped us identify diverse potential pathways, our study did not further measure, via more refined experimental designs, which course design or implementation elements enhanced students' self-efficacy. Future research could design targeted experiments to verify the mechanisms, building upon the pathways identified in our study. Lastly, the study could have included additional variables, such as students' academic performance, and considered differences in the effects of similar nature education programs across urban and rural contexts.

To maximize the impact of nature education on future generations, particularly rural children, designing programs centered on self-efficacy development is crucial (Huang et al. 2022). Given the regional imbalance in nature education availability in China, with urban areas receiving more attention, rural settings may be restricted by limited resources. Despite their close proximity to nature, rural children have fewer nature-education opportunities. Moreover, implementing strategies like hands-on activities, group learning, and positive reinforcement could be challenging for teachers in rural schools. This might be because of the pressure of academic performance and the extra time and effort required. However, this also presents a significant yet untapped opportunity for impactful nature education initiatives.

Currently, China's Ministry of Education is promoting extracurricular activities to foster the all-round development of students, compelling schools to introduce nature education courses. We propose that these courses address the existing challenges of nature education in rural areas by integrating teaching strategies into innovative educational tools, such as video-based courses and practical kits similar to those used in the Wildlife Course, making it easier for teachers to deliver nature education regardless of limited school resources (Kossybayeva et al. 2022). Meanwhile, our research indicates that teachers can apply the teaching methods from the Wildlife Course to other subjects with positive results. More importantly, such courses create a more equitable learning environment where students can showcase diverse talents beyond grades, enabling teachers to recognize every student's potential. To ensure effectiveness, future courses need to be customized to the specific needs of rural students, guided by feedback from both students and local teachers (Balaguer et al. 2020). Continuous evaluation and refinement of program content and delivery are crucial to keep nature education relevant in a rapidly changing world.

Author Contributions

Zhijian Liang: conceptualization, formal analysis, visualization, writing – original draft, investigation, methodology, writing – review and editing. Lin Chen: conceptualization, writing – review and editing, project administration. Junying Ren: project administration. Changning Liu: methodology, writing – review and editing. Kaiwen Zhou: methodology, writing – review and editing. Tien Ming Lee: supervision, writing – review and editing. Sifan Hu: conceptualization, writing – review and editing, validation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the teachers and students who participated in or assisted with our evaluation, as well as the ten schools in the Wildlife Course program. The Wildlife Course program was funded by the Shanghai Soong Ching Ling – the Bank of East Asia (BEA) Charity Fund.

Ethics Statement

Authors confirm that they have adhered to the journal's ethical guidelines as noted on the journal's author guidelines page. All data were anonymized and used only for research purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.