Social and cultural aspects of human–wildlife conflicts: Understanding people's attitudes to crop-raiding animals and other wildlife in agricultural systems of the Tibetan Plateau

社会和文化视角下的人与野生动物冲突:青藏高原农区居民对肇事动物与其他野生动物的态度研究

Abstract

enThe social dimensions of human–wildlife conflicts are becoming increasingly important. In regions where crop-raiding is a common issue, local people's attitudes toward wildlife is an important indicator of how successful conservation efforts are likely to be. One such area is the east Tibetan Plateau—a biodiversity hotspot with well-preserved forest ecosystems and mountain villages where subsistence farming is practiced. In this context, we conducted a survey of people's tolerance toward wildlife in five Tibetan villages that experience conflicts arising from crop-raiding incidents. We interviewed 83 respondents, 76 of whom were participants in a compensation scheme that provided payments for crop damage. Wildlife tolerance was generally high, mostly due to mutualistic wildlife values, whereby people believed they should coexist with animals equally instead of exploiting them as natural resources. Tolerance was influenced by people's wildlife preference rather than the level of damage to croplands: people were likely to show higher tolerance toward culturally important species even when they were crop-raiding animals. While economic and mitigation efforts as part of traditional conservation management led to increased tolerance, the compensation scheme and fencing were less important than wildlife preference. We suggest that conservation management for human-wildlife conflicts should develop region and stakeholder-specific engagement strategies. Crucially, such strategies should incorporate cultural considerations to fully address the complex human dimensions inherent in these issues.

摘要

zh人兽冲突中的社会科学视角正在变得越来越重要。在野生动物食用农作物的冲突频发地区,当地人对野生动物的态度是衡量保护工作成功与否的重要指标。位于生物多样性热点地区的青藏高原东部农区便是该类型区域的其中之一,这里森林生态系统保存完好,农区山地居民以自给农业为主。在此背景下,本研究针对因野生动物肇事而农作物受损高发的5个藏族村庄,调查了其村民对野生动物的容忍度。研究采访了83户村民,其中76户参与过针对作物损失的人兽冲突补偿项目。结果显示,受访者对野生动物的容忍度普遍较高,主要是由平等共生的野生动物价值观影响,人们认为他们应该与动物平等共存,而不是将其视作自然资源加以利用。容忍度受人们对野生动物的偏好所影响,而不是农田被破坏的程度,特别在文化上有一定意义的肇事动物,人们也通常对其表现出更高的容忍度。虽然经济手段和缓解措施作为传统保护管理的一部分,能在一定程度上提高人们的容忍度,但在此研究中补偿计划和围栏在针对容忍度的影响方面并没有人们对野生动物的偏好程度影响大。我们建议,人兽冲突的保护管理应制定针对特定区域以及特定利益相关方的具体策略。至关重要的是,这些策略应将本地文化因素纳入考量,以充分解决人兽冲突所固有的复杂的人文因素问题。【审阅:李梦姣】

Plain language summary

enIn the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau, people in agricultural areas often face the problem of wild animals eating their crops. Understanding how local farmers feel about these wild animals is crucial for ensuring effective conservation efforts. We interviewed people in five villages where animals eating crops is a significant problem. Most of the 83 people we spoke with were part of an initiative compensating them financially when animals damage their crops. We discovered that most people have positive feelings toward wildlife, mainly because they believe in living together with animals in harmony, not just exploiting them as natural resources. Interestingly, how much people liked certain animals affected their feelings more than how much damage their crops suffered. For example, if an animal was important to their culture, they were more likely to put up with it eating their crops. Even though giving financial compensation for crop damage and trying other ways to stop animals from eating crops helped people be more tolerant, what really mattered was how much they liked wildlife in general. We think that the plans to solve human–wildlife conflicts should be tailored to fit each specific area and group of people, taking the local culture into consideration when doing so. In this manner, we can better understand the complex reasons behind people's attitudes toward wildlife.

通俗语言摘要

zh在青藏高原东部,农区的人们经常面临野生动物食用庄稼的问题。了解当地村民对这些野生动物的态度对于确保有效的保护工作至关重要。我们采访了5个村庄的村民,他们面临着具体的野生动物食用庄稼的问题。在我们采访的83户中,大多数人参与过一个人兽冲突补偿项目,当野生动物破坏了作物时,他们将会得到一定的经济补偿。我们发现,大多数人对野生动物有积极的情感,主要是因为当地人相信应该与动物平等共生,而不是将其视作自然资源加以利用。有趣的是,人们对某些野生动物的情感往往更受对其喜爱程度的影响,而不是农作物受到的损害程度。例如,如果某种动物在文化上有一定的意义,人们更愿意去容忍它吃掉部分自己的农作物。针对作物损失给予经济补偿,并尝试其他缓解措施阻止该类冲突的发生,这些举措都有助于增加人们的容忍度,但研究显示在此地区更重要的是人们整体有多喜爱野生动物。我们认为,致力于解决人兽冲突的方法需要区分特定的地区和人群,充分考虑到当地文化。这样,我们才能更好地理解人们对野生动物态度背后的复杂原因。

Practitioner points

en

-

Understanding the social dynamics of human communities is a crucial part of human–wildlife conflict resolution.

-

Conservation practitioners should avoid inferring a direct correlation between conflicts and retaliatory actions and avoid creating opposition; a broader spectrum of social factors should be considered in conflict management.

-

Tailoring conservation management to the local context and actively engaging all relevant stakeholders are essential steps for the overall success of conservation initiatives.

实践者要点

zh

-

了解人类社区内的社会动力是缓解人兽冲突的关键部分。

-

保护实践者应避免首先就将冲突与报复行为直接关联起来制造对立;在冲突管理中应考虑更广泛的社会因素。

-

根据当地情况量身定制保护管理策略,并争取所有利益相关方的积极参与是保护举措取得全面成功的重要步骤。

1 INTRODUCTION

The world's human population increased by one billion people between 2010 and 2022 (United Nations), and related anthropogenic changes in natural resource management and land use are having increasingly profound impacts on the global environment (Lewis & Maslin, 2015). Habitat loss and fragmentation are identified as the most important current threats to biodiversity in the latest IPBES report (IPBES, 2019). Concurrently, habitat degradation decreases food quality and availability for wildlife in natural systems, along with climate change intensifying potential and existing human–wildlife conflicts (Abrahms et al., 2023; Manfredo, 2015). These conflicts can cause losses to local people's livelihoods and reduce their support for conservation efforts in general (IUCN, 2023; Redpath et al., 2013). In some cases, such conflicts can further lead to the retaliatory killing of animals, which constitutes the primary factor driving the extirpation of large carnivores (Frank et al., 2005; Gross et al., 2021).

The complexity of the human dimension in wildlife conflicts is increasingly recognized as a crucial facet in conservation management, and requires multidisciplinary approaches to fully capture its different aspects (Decker et al., 2012; Game et al., 2014; Redpath et al., 2013). Indeed, the mitigation of human–wildlife conflicts, with the aim of fostering coexistence, is explicitly included in the global Convention on Biodiversity framework, as Target 4 of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD, 2022). Conservation management can inadvertently act as a catalyst for conflict by impacting how people use and manage natural resources (Skogen, 2017). Previous research has assumed that the main driver of people's intolerance and retaliatory killing behavior was the damage done to crops by animal raids. Therefore, studies have focused mainly on technological mitigation solutions, such as fences, alternative food sources, and landscape barriers, as well as monetary compensation to individual households and legal prohibitions (Breitenmoser et al., 2005; Dickman et al., 2012; Kansky et al., 2016). The damage caused by wildlife can affect local people not only through financial loss but also through substantial social costs, including food security, health, labor, and psychological well-being. Thus, while quantifying the damage and promoting mitigation techniques are obvious responses, they cannot adequately address the full range of aspects of human–wildlife conflicts (HWC) (Hill, 1997; Naughton-Treves & Treves, 2005; Webber & Hill, 2014).

Tolerance toward negative wildlife interactions with humans is defined by Kansky (2015) as “the ability and willingness of an individual to absorb the extra potential or actual costs of living with wildlife.” It can be determined by a combination of individual perceptions and attitudes, values, social norms, and cultural and religious contexts (Ajzen, 1991; Madden & McQuinn, 2017). Understanding local people's tolerance toward wildlife, and the factors that determine it, is a prerequisite for conservation and natural resource managers to develop effective strategies for mitigating conflicts and achieving long-term conservation goals. However, the convergence of multiple factors complicates wildlife tolerance, causing it to vary across different contexts (Hill et al., 2017). Biosocial research on HWC and coexistence is still minimal, although it is starting to increase (Kansky & Knight, 2014; Treves & Bruskotter, 2014). Until recently, only a few quantitative syntheses and meta-analyses on stakeholders' attitudes toward wildlife were available, and some of them focused solely on overall attitudes toward carnivores rather than specifically on HWC (Dressel et al., 2015; Kansky & Knight, 2014; Williams et al., 2002). There remains an urgent need for more information from case studies around the world to allow us to further build on our knowledge of the broad patterns across different landscapes and cultural contexts.

Consequently, the aim of this study was to understand people's tolerance toward crop-raiding species and to examine the association between this tolerance and sociocultural, practical, and economic factors. Employing a multiyear data set derived from a novel compensation scheme across five Buddhist villages on the east Tibetan Plateau (Yang et al., 2019; Supporting Information S1), and an extensive questionnaire-based survey, we explored the various factors that shaped the local residents' tolerance toward wildlife. We anticipated that religiosity, mitigation, and compensation would be the key drivers of tolerance. Our findings will provide potential pathways to address HWC issues in this region and will enhance the general understanding of the factors underpinning human tolerance toward wildlife.

2 METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1 Study area

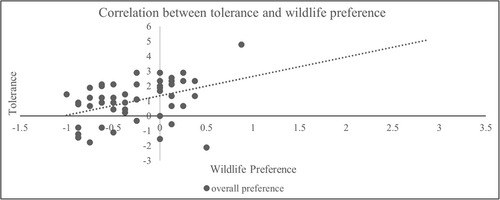

Yajiang is on the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau in Southwest China (Figure 1). This region lies within one of the 36 global biodiversity hotspots—the Mountains of Southwest China. The mountainous terrain of the region harbors the most botanically diverse temperate forest ecosystems globally, with 12,000 plant species, 300 mammal species, and 686 bird species—many of which are endemic to the area (Mittermeier et al., 2011). The milder temperatures of the Yarlung River valley, a tributary of the Yangtze River, make it one of the few agricultural areas on the Tibetan Plateau (d'Alpoim Guedes et al., 2014). The questionnaire-based interviews were conducted in five villages: Tangzu, Reri, Malangcuo, Tarihe, and Marihe. These five villages are situated in proximity to the renowned Zhaga Monastery in Yajiang, a significant center of Buddhist worship. Owing to religious and traditional taboos against any form of destruction on the sacred mountain of the monastery, coupled with regular conservation patrol activities organized by the monastic community, the primary forest has been preserved. Consequently, apex predators, endemic ungulates, and birds are all recorded here. The altitude of the villages ranges from 2500 to 3700 m.a.s.l., restricting agriculture to subsistence crops such as Tibetan barley, wheat, potato, and maize. Unlike pastoralist communities, people raise a small number of livestock in close proximity to their dwellings, and as is the case for communities at the edge of the forests, there is no distinct threshold between forest and cropland, making it easy for wild animals to forage in village areas, thereby heightening the susceptibility of the local people to HWC. Between 2010 and 2019, a compensation scheme operated in these five villages for people suffering crop damage or loss. The damage was quantified according to the area affected and mitigation measures, and data were recorded by village representatives. The local forestry bureau compensated part of the recorded crop loss on an annual basis, and the monastery, as an independent third party, supervised both the villagers and the forestry bureau to guarantee transparency across the whole process (Yang et al., 2019).

2.2 Tolerance questionnaire

Targeted sampling was conducted based on the participant list of the compensation scheme, and haphazard sampling was also used to collect answers to general questions from any respondents who happened to be at home and agreed to be interviewed. The interviews were conducted in the local Tibetan language, with local forestry staff acting as translators. After excluding unquantifiable interview responses due to answer reliability and translation difficulties, data from 83 households in total were used: 55% of the total number of households (n = 150) across the five villages. A total of 76 households, out of the 83 surveyed, had joined the compensation scheme, and they represented 56% of all participants of the compensation scheme (n = 136). The villagers were asked five questions relating to their tolerance of wildlife species (Questions 1–5; Table 1). The questions were developed based on previous research (Bruskotter et al., 2015; Cerri et al., 2017; Kansky, 2015; Kansky & Knight, 2014).

| Question | Scoring allocation |

|---|---|

| 1. Do you like some animals living around your house and cropland? | 1: yes; 0: yes with conditions; −1: no or do not know |

| 2. Do you allow animals to eat some of your crops? | 1: yes; 0: yes with conditions; −1: no or do not know |

| 3. Do you think it is right to kill some crop-raiding animals? | 1: No, it is wrong; 0: yes, some of them; −1: yes, kill them all |

| 4. Are you happy to see the species increase in numbers? | 1: yes; 0: no feelings or do not know; −1: no |

| 5. Should the species be protected? | 1: yes; 0: no feelings or do not know; −1: no |

Responses to Questions 1 and 2 were coded as 1 (yes), 0 (yes conditional on some species being excluded or in low numbers), or −1 (no or do not know). Question 3 asked people whether it was right to kill animals. If respondents answered it was right to kill all crop-raiding animals, the answer was coded as −1. The “yes, kill some of them” answer was coded as 0; “no, it is wrong to kill” was coded as 1. Questions 4 and 5 were posed specifically regarding eight different species: the leopard (Panthera pardus), Lord Derby's parakeet (Psittacula derbiana), the porcupine (Hystrix brachyura hodgsoni), the wild boar (Sus scrofa), the Tibetan macaque (Macaca thibetana), the white-eared pheasant (Crossoptilon crossoptilon), the Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus), and the wolf (Canis lupus). The responses to these two questions were coded by calculating the mean value from the scores attributed to the eight species. For each question, scores were aggregated, resulting in an overall tolerance score for each respondent that ranged from 5 (high tolerance) to −5 (low tolerance).

2.3 Attitudes toward wildlife

We used Likert-scale questions (five categories, ranging from −2 to 2) to gauge attitudes toward the eight species under consideration. This approach was based on the premise that species preference significantly informs attitudes, which in turn are indicative of tolerance levels. The overall attitude score was derived from the mean value of the preference scores of the eight species. Species with sufficient data points were then further grouped into different categories: crop-raiding animals (porcupine, wild boar, and white-eared pheasant) and carnivores (leopard, Asiatic black bear, and wolf). To avoid confusion, images of the animals were shown to the respondents. Information was also collected for the explanatory factors of tolerance by asking questions about wildlife experiences (i.e., How many species have you seen in the wild before?), mitigation effectiveness (i.e., Do you think your fence is useful for preventing the crop-raiding animals?), financial investment on mitigation (i.e., How much money did you spend on fencing?), wildlife ownership (i.e., Who do you think the wildlife belongs to?), awareness of protection laws (i.e., Do you know the wildlife protection laws?), and religious practices to evaluate the level of belief (i.e., How many times have you recited the six-words mantra? How often do you attend the assembly organized by the Zhaga Monastery? Did you participate in the construction of the monastery? Did you take part in the conservation patrols (such as antipoaching and waste collection)? Demographic data, including age, gender, education, and annual income, were collected as other important explanatory factors. Project records of compensation payments and the cropland size of each household from local forestry bureau records were also included. These explanatory variables were in line with previous review studies (Bruskotter et al., 2015; Dickman, 2010; Kansky & Knight, 2014; Naughton-Treves & Treves, 2005). See Supporting Information S2 for the full questionnaire.

2.4 Mitigation measures

Mitigation measures (fencing) indicated the willingness of villagers to invest in preventing damage from wildlife and likely reflected tolerance to some extent. However, as an explanatory factor of tolerance, the efficacy—or lack thereof—of fencing and the resultant frustrations from failed mitigation measures may actually decrease people's tolerance toward wildlife, especially “problem wildlife” (Kansky & Knight, 2014). Given that mitigation measures are fundamental in conflict management, we conducted a simple mitigation effectiveness assessment to explore the mitigation measures in these five villages relating to fence type, financial investment, time investment, and mitigation action effectiveness. The perceived effectiveness was derived from the interviews with the respondents, and the actual effectiveness was calculated based on the recorded damage data from the compensation scheme (see Section 2.5).

2.5 Wildlife damage

The five villages participated in the compensation scheme for several years, and damage and compensation payment data were recorded and updated every year. All recorded damage data, compensation payments, and cropland size of each household were acquired from the local forestry bureau. The total cropland of each household was measured in the field by the local forestry bureau staff and a local conservation NGO between 2011 and 2014 (Yajiang Forestry Bureau, 2017). Since logging and reclaiming new cropland have been strictly restricted in this region since the late 1990s, the size of cropland remains stable.

With respect to the perceived damage from each crop-raiding animal, we asked respondents to rank the crop-raiding animals in order of problems they caused and to specify the level of damage caused by each crop-raiding animal. The perceived damage of each species was categorized as low (20%–40% of their cropland area), medium (40%–60%), and high (60%–100%).

2.6 Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 24 was used to analyze the data. Kruskal–Wallis tests with pairwise comparison were used to test the difference between groups, including the preference and damage perception between different crop-raiding animals. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to test for differences in wildlife preference between the crop-raiding animal group and the carnivore group, wildlife encounter experience at different locations (wild and cropland), differences in perceived mitigation effectiveness between fence investment categories, and for the mantra recital difference between age groups. Spearman Rank Order Correlation was used to test the correlations between cropland size and fence cost, and with actual damage; and Person correlation coefficient and χ2 test were used to test the mitigation effectiveness for different aspects of fencing, such as financial investment, time, and combinations of fence types.

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were conducted to test the associations between tolerance, as the dependent variable, and its potential explanatory factors. The GLMs included categorical data such as age, gender, and perceived damage as fixed factors and continuous data such as wildlife preference, wildlife experience (number of species people encountered in the local area), damage area, compensation payments, and financial investment in mitigation measures, as covariables.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic profile

Among the 83 respondents, each representing one household, there were 47 (56.6%) male and 36 (43.4%) female respondents, and over half were in the age range 41–60 years (53%). There was a high illiteracy rate; 85.5% of respondents had no formal school education. The main family annual income source was from collecting caterpillar fungus (Ophiocordyceps sinensis) and matsutake mushroom (Tricholoma matsutake), and 65% of respondents made more than 10,000 (CNY) in 1 year (Table 2). All the respondents were Tibetans and self-described as “absolute Buddhist.” A total of 87.9% of respondents attended the Buddhist assembly organized by the monastery every time, 98.8% of respondents participated in the voluntary reconstruction of the monastery, and 83.1% of respondents or their family members took part in the sacred mountain conservation patrol activities every year, typically three–four times a year, which were organized by the monastery and self-funded. The age or gender limitations were most apparent in patrol activities: only young, physically fit men were allowed to participate. The only significant difference in mantra recitals was between age groups (Table 3). People over 60 years old recited the religious mantra (six true words) more times every day than other age groups. Therefore, the only differences in the answers to the questions about religious practices were due to age or gender restrictions.

| Characteristics | Proportion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47 (56.6%) | Female | 36 (43.4%) |

| Age | 18–29 | 8 (9.6%) | 30–40 | 20 (24.1%) |

| 41–60 | 44 (53%) | 60+ | 11 (13.2%) | |

| Education | Schooled | 12 (14.5%) | Unschooled | 71 (85.5%) |

| Annual incomea (CNY) | <10,000 | 29 (35.4%) | >10,000 | 53 (63.8%) |

- a There were 82 answers for annual income: one respondent declined to answer.

| Statistical tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal–Wallis test | H statistic | df | p Value |

| Species preference: pheasant, boar, porcupine | 178.607 | 2 | <0.001** |

| Damage perception: pheasant, boar, porcupine | 130.095 | 2 | <0.001** |

| Mann–Whitney test | U | n1, n2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mantra recitation by age group (>60 vs. <60 years) | 697.5 | n1 = 37.18 n2 = 69.41 |

<0.001** |

| Wildlife preference: crop-raider and carnivores | 35,994.5 | n1 = 269.56 n2 = 229.44 |

<0.001** |

| Wildlife encounter experience at different locations: wild and cropland | 9831.5 | n1 = 141.62 n2 = 218.56 |

<0.001** |

| Perceived mitigation effectiveness: whether invest on fence | 1132 | n1 = 34.2 n2 = 48.45 |

0.001a |

- a Level of significance.

3.2 People's attitude toward different animal groups and in different contexts

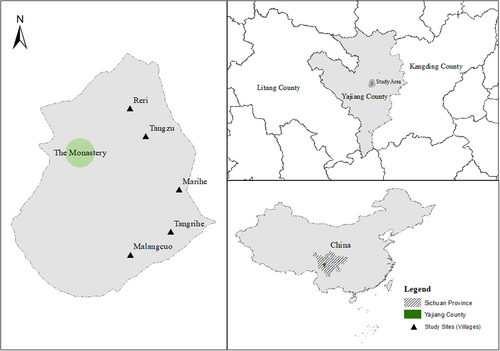

People's preferences between animal groups differed significantly: crop-raiding animals were less preferred than carnivores (Table 3). Between the crop-raiding animal groups, there was a statistically significant difference in preference between white-eared pheasants and the other two, wild boars (p < 0.001**) and porcupines (p < 0.001**). Of these three crop-raiding species, people favored white-eared pheasants, which were most frequently seen in the fields: 90.4% of respondents reported encountering white-eared pheasants on their cropland. There was no significant difference in preference between wild boars and porcupines (p = 0.915) (Figure 2). People in the five villages reported a high frequency of wildlife encounters. On average, each respondent observed 10 different species during the previous year. There was a statistically significant difference in feelings about wildlife experiences at different locations between those in the wild and those in cropland (Table 3). People tended to have positive feelings (76.1%, n = 142 encounters) when they encountered pheasants, ungulates, and other animals in the wild, with fewer instances of negative feelings (15.4%, n = 142 encounters) and no feelings (8%, n = 142 encounters). Conversely, when they encountered crop-raiding animals in cropland, people tended to have negative feelings (56.1%, n = 157 encounters) rather than positive feelings (39.5%, n = 157 encounters) or no feelings (4%, n = 157 encounters). Most (78.3%, n = 65) people believed wildlife ownership should lie with the government. However, when asked about who should take responsibility for protecting these animals, 51.8% of respondents (n = 43) chose “everyone.”

3.3 Perceived and actual damage

Using data available for the 83 household respondents, the average size of cropland owned by each household was 0.33 ± 0.19 ha, and the average area of damage per household was 0.04 ± 0.04 ha. Approximately 2.6% (n = 2) recorded damage that could be categorized as “high damage” (60%–100% of the cropland area of a household), and 88.3% (n = 73) recorded damage categorized as “low damage” (0%–39% of the cropland area). There was a statistically significant positive correlation between the damage loss and the cropland size of each household; the more cropland cultivated, the more damage was recorded (Table 4). The average compensation payment was CNY516.1 ± 311.33 per household for loss during the years before the survey was conducted. A total of 75.9% of respondents (n = 63) ranked wild boar as the worst crop-raiding animal. There was a significantly different perception of damage caused by the crop-raiding animals (Table 3 and Figure 2). Wild boar was perceived to cause more damage than porcupine (p = 0.002*) and white-eared pheasant (p < 0.001**). And between white-eared pheasant and porcupine, less damage was perceived from white-eared pheasant (p < 0.001**; Figure 2).

| Statistical tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman's correlation | R statistic | p Value | |

| Cropland size and fence cost | 0.289 | 0.008a | |

| Cropland size and amount of damage | 0.401 | <0.001** |

| Pearson correlation coefficient | r | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigation effectiveness: fence and damage (investment) | 0.2 | 0.07 |

| χ2 test | χ2 | df | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigation effectiveness: fence and damage (time) | 271.154 | 280 | 0.999 |

| Mitigation effectiveness: fence and damage (combination fence types) | 287.977 | 280 | 0.359 |

- a Level of significance.

3.4 Mitigation measures and effectiveness

The mitigation measures in our study sites were fences. A total of 92.8% (n = 77) of respondents replied that they built fences around cropland. There were five types of fences to prevent crop-raiding animals: thorny branches (22%), wooden board (1.3%), stone (1.3%), hand-made wire fencing (3.9%), and commercial iron fencing (14.3%). Most respondents (57.1%) used a combination fence with at least two fence types, which differed from single material fences in terms of structure and stability. Only the commercial iron fence and wire fence required financial outlay; the average money spent on fencing per household was CNY377.7 ± 454.6, and 54.2% of households (n = 45) spent 1 week building their fence. The fence cost was positively correlated with the cropland size (Table 4). Approximately 61.4% of the households (n = 51) believed the fences were not useful. Thus, perceptions of mitigation effectiveness were significantly different between those who had made a financial investment and those who had not (Table 3). People who spent more money on fencing felt that the fence was useful, while those who spent less money believed the fence was not at all useful. However, no significant correlation existed between actual damage and mitigation (fencing) investment, time spent building fences, and the number of fence types used in combination fencing (Table 4).

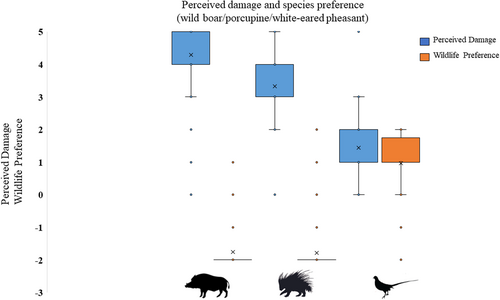

3.5 Tolerance toward crop-raiding animals and its driving factors

Our quantitative surveys across 83 households in five villages showed that the average tolerance score toward animals was 1.02 ± 1.41, denoting a positive preference (n = 83; range from −5 to 5; Figure 3). The GLMs result showed that there was significant correlation between tolerance and the explanatory variable wildlife preference (p < 0.001**). There was no significant correlation between tolerance and wildlife experience, perceived/real damage, compensation payments, financial investment into fencing, and other demographic factors (Table 5). People with a higher wildlife preference had a higher tolerance than others.

| Parameter | B | SE | Wald χ2 | df | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 1.206 | 0.9436 | 1.633 | 1 | 0.201 |

| Wildlife preference | 1.524 | 0.2918 | 27.290 | 1 | <0.001** |

| Wildlife experience | 0.003 | 0.0820 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.971 |

| Compensation | 0.001 | 0.0007 | 0.569 | 1 | 0.451 |

| Total damage area | 0.078 | 0.0891 | 0.771 | 1 | 0.380 |

| Fence cost (yuan) | 0.000 | 0.0003 | 0.314 | 1 | 0.575 |

| Perceived damage = 1 | −0.092 | 0.4037 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.821 |

| Perceived damage = 2 | −0.290 | 0.4254 | 0.464 | 1 | 0.496 |

| Perceived damage = 3 | 0a | . | . | . | . |

| Age = 1 | −0.083 | 0.2999 | 0.076 | 1 | 0.783 |

| Age = 2 | 0a | . | . | . | . |

| Gender = 1 | −0.348 | 0.3477 | 1.000 | 1 | 0.317 |

| Gender = 2 | 0a | . | . | . | . |

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 The importance of recognizing local and cultural value systems in tolerance attitudes

The cognitive hierarchy framework, which integrates values, value orientations, attitudes and norms, behavior intention, and behavior, has been applied to explain and predict human response when conflict occurs (Cerri et al., 2017; IUCN, 2023; Manfredo et al., 2009). In our study, overall wildlife preference was the key factor affecting people's tolerance. We also found that people's preference for wildlife was different between animal groups and that resentment toward crop-raiding animals did not affect feelings toward other animals. Wildlife experiences played an important role in people's preference toward wildlife at different locations: our respondents had more positive experiences in the wild and more negative experiences in croplands. The white-eared pheasant in our study was a good example of how cultural values and value orientation influenced people's tolerance toward wildlife. Although it was ranked as one of the top three crop-raiding animals, and 85% of respondents reported daily encounters with it in cropland, people still had a higher positive attitude toward it than other crop-raiding animals, perhaps because this species is considered sacred in Tibetan culture: its conspicuous white is a symbolic color for Tibetan Buddhists (Wang et al., 2012).

Previous studies showed that people on the east Tibetan Plateau orientated themselves with nature by following the Buddhist teachings of sacred nature sites, sin, cycles of karma, and empathy and equity of all beings (Woodhouse et al., 2015). These values mean that people hold non-utilitarian feelings toward animals, and consider animals part of their society (Manfredo et al., 2009). In line with this, Bhatia et al. (2017) found positive associations between religiosity and attitude toward two carnivores in Buddhist villages. Similarly, Gogoi (2018) reported that people's tolerance was high despite stressful experiences with elephants because the elephant is a culturally important animal in India. While the highly homogeneous religiosity in the five villages in our study meant that we could not say definitively whether religion was a key factor driving people's tolerance, it is likely that it is important. There are few studies on how people's traditional values for wildlife, especially regarding culture and religion, contribute to wildlife tolerance in this region; more research is needed on this subject. Also, for conservation practitioners addressing HWC in the region, negative experiences and retaliatory behavior may not be directly correlated, due to the complexity of the local context: assumptions around the drivers of behavior may be incorrect (cf. cognitive hierarchy framework). Thus, we must consider attitudinal factors—how people consider their relationship with the natural world and other species—in different parts of the conflict management process (Dickman, 2010; Manfredo et al., 2009).

4.2 The limitations of traditional HWC management for conservation

Traditionally, a wide range of economic schemes, such as compensation, insurance, and conservation payments, are applied in conflict management with the aim of both offsetting the costs to those affected and increasing tolerance for wildlife (Naughton-Treves & Treves, 2005; Nyhus, 2016; Treves & Bruskotter, 2014). Between 1999 and 2015, US$222 million was paid in compensation to offset the damage caused by wildlife globally (Ravenelle & Nyhus, 2017). However, tangible cost was less important than intangible cost in explaining people's attitudes toward wildlife (Kansky & Knight, 2014). This was in line with our study, where neither actual crop damage caused by animals, nor the insurance compensation payments for the damage, were correlated with people's tolerance. Paradoxically, previous studies looking at economic payments have shown that if the compensation is far less than the market value (e.g., due to lack of funds, as in the case of this study), tolerance for wildlife might not be associated with compensation payments (Dickman et al., 2011). In contrast, where compensation is high enough to cover the damage costs and opportunity costs, it may then lead to “moral hazards”—where people intentionally make false damage claims—resulting in negative impacts on conservation. High subsidies might even encourage agricultural expansion and habitat conversion, which could further push the local communities into a “poverty trap” due to intensified competition for shared and limited natural resources (Bulte & Rondeau, 2005; Ravenelle & Nyhus, 2017).

Another typical component of conflict management is various mitigation measures, such as physical barriers, guarding, early-warning systems, deterrents, and aversions (IUCN, 2023; Treves et al., 2009). While the mitigation measures in our study (fences) did not effectively prevent damage from animals, they had a positive outcome in another way: people's perception of fence effectiveness increased their tolerance toward wildlife. The villagers who spent more money on fencing were likely to perceive it as useful and likely to have higher tolerance. This emphasizes the necessity to integrate approaches that consider the human dimension, which should be informed by affected stakeholders within the local context (IUCN, 2023).

4.3 The importance of engaging all stakeholders in conflict management

Madden and McQuinn (2017) posited that there were three types of conflict that formed a conflict framework. At the top was dispute conflict, which was clearly evident and easily articulated. However, dispute conflict was just the tip of the iceberg, and the more important types of conflict were underlying conflicts—those unresolved or unsatisfactorily solved historical conservation conflicts between different stakeholders—and deep-rooted conflicts that challenge social identity and values. For instance, once wildlife with a severe negative interaction becomes characterized as a vicious species in local culture, tolerance would remain low even with the conflict removed. As part of biodiversity conservation conflicts, HWC can be presented in different ways between different interest groups (Hill, 2017). This is attributable to the involvement of multiple stakeholders who sometimes hold conflicting standpoints (Peterson et al., 2010; Redpath et al., 2013; Young et al., 2010), bringing about confrontations on how best to manage wildlife (Draheim et al., 2015). Thus, engaging all stakeholders in the process, generating trust, and enhancing acceptance between them are key aims in conservation conflict management (Carpenter et al., 2000; Young et al., 2016). In this study, the stakeholders were five local communities, the monastery, an NGO, and the local forestry bureau. The local forestry bureau decentralized power to local communities by allowing them to assess the damage loss themselves. The monastery played an important role in helping to generate trust among the stakeholders, acting as a neutral stakeholder to supervise the legitimacy of the loss assessment in compensation schemes, and adding authority to local communities when they negotiated with the local forestry bureau. The NGO played a facilitator role and helped to connect funding resources. Additionally, the monastery's Buddhist teaching determined local people's values and, in addition to the sacred mountain patrols every year, facilitated the raising of local people's conservation awareness, and promoted conservation as the mutual goal among all stakeholders. Therefore, despite ongoing crop-raiding conflicts, people's tolerance in this region was generally high, and their attitudes toward wildlife positive. Despite most people experiencing crop-raiding and perceiving that ownership of wildlife lies with the government, half of the respondents considered that it should be everyone's responsibility to protect wildlife.

4.4 The influential factors of demography

Our result was in line with the previous finding that socio-demographic variables were poor predictors of attitudes toward animals (Kansky & Knight, 2014). However, other studies have shown strong relationships between socio-demography and these attitudes (Bhatia et al., 2017; Kleiven et al., 2004; Ogra, 2008; Suryawanshi et al., 2014). We should not simply assume that socio-demographic factors are only useful for describing populations because tolerance could be region-specific. Therefore, demographic variables should be included in assessments of tolerance in each case. They can be useful for developing contextually relevant local adaptive strategies for wildlife conflict management.

5 CONCLUSION

The complexity of the human dimension of wildlife conflict management has been a focus of biodiversity conservation in recent years because HWC challenges both wildlife conservation and people's livelihoods, as well as impacting most of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Decker et al., 2012; Gross et al., 2021; IUCN, 2023). The human dimension—the crucial part of HWC resolution—requires a social science perspective to understand what drives people's attitudes and to identify best practice management solutions (Kansky & Knight, 2014).

This tolerance study contributes to the development of social perspectives in conflict management. It is one of few studies conducted in the east Tibetan region where people hold mutualistic values toward nature and generally have a high tolerance for HWC situations. In evaluating the effectiveness of traditional conflict management, comprehensively assessing the drivers of people's attitudes toward different animal groups, and identifying how these attitudes affect general tolerance in this specific cultural context, we provide additional valuable insights. Furthermore, combining our indicators with other available studies provides more knowledge to guide the development of tolerance models and theories.

Ultimately, conservation conflict management requires the recognition of different levels of conflict alongside the importance of stakeholders' values and attitudes in local contexts (Decker et al., 2012; Madden & McQuinn, 2017). It is a challenge to balance stakeholders' tolerance with conflict and create an effective participatory process leading to a common consensus among stakeholders (Kansky et al., 2016; Young et al., 2016). In some cases, traditional conflict management does not achieve its purpose. Therefore, conservation practitioners should develop management strategies that engage all stakeholders and reflect local contexts to ensure conservation funds are used more efficiently.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mengjiao Li: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft. Wei Jiang: Investigation; project administration. Bajin Li: Project administration; resources. Nathalie Butt: Writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to give my gratitude to Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent for providing a well-designed master program and the financial support of my study. I would also like to thank my supervisor at that time Tatyana Humle for supporting my study in all kinds of way and setting a great model of rigorous and professional scholar to me. I thank Shanshui Conservation Center for providing me opportunity and connection with this amazing human wildlife conflict project and Yajiang Forestry Bureau for the strong partnership and support not only for this study, but also for the 7 years' collaboration of the community-based conservation project. Thank Xiaoling LI for the interview translation, I couldn't finish the field survey without her. At last, thanks to the local communities for participating in my study, and for their long-time efforts on conserving their beautiful home where leopard, wolf and many beautiful endemic species thrive.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known conflict of interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the project reported in this paper.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All the methods in this study were approved by the University of Kent in 2018. Only those people who gave oral consent, due to the high illiteracy rate in this region, were included in the study and information about the study was explained before the interview. The participation of survey was voluntary.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.