Caregiving in Asia: Priority areas for research, policy, and practice to support family caregivers

Abstract

Population aging presents a growing societal challenge and imposes a heavy burden on the healthcare system in many Asian countries. Given the limited availability of formal long-term care (LTC) facilities and personnel, family caregivers play a vital role in providing care for the increasing population of older adults. While awareness of the challenges faced by caregivers is rising, discussions often remain within academic circles, resulting in the lived experiences, well-being, and needs of family caregivers being frequently overlooked. In this review, we identify four key priority areas to advance research, practice, and policy related to family caregivers in Asia: (1) Emphasizing family caregivers as sociocultural navigators in the healthcare system; (2) addressing the mental and physical health needs of family caregivers; (3) recognizing the diverse caregiving experiences across different cultural backgrounds, socioeconomic status, and countries of residence; and (4) strengthening policy support for family caregivers. Our review also identifies deficiencies in institutional LTC and underscores the importance of providing training and empowerment to caregivers. Policymakers, practitioners, and researchers interested in supporting family caregivers should prioritize these key areas to tackle the challenge of population aging in Asian countries. Cross-country knowledge exchange and capacity development are crucial for better serving both the aging population and their caregivers.

Abbreviations

-

- LTC

-

- long-term care

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the past century, global life expectancy has more than doubled due to advancements in healthcare and other sectors. In Asia, life expectancy continues to increase, reaching an average of 74.2 years in 2019, up from 68.6 years in 2000 [1]. Preliminary estimates indicate that by 2050, the population aged 60 and older in Asia will surpass 1.3 billion, accounting for 36.8% of the total population—a significant increase from the current 17.2% [2]. In 2016, the population aged over 80 years in Asia represented 53% of the global total, amounting to 68 million people, or 1.5% of the region's population. This proportion is expected to reach 5%, totaling 258 million by 2050 [3]. The rapid growth of the oldest old population, along with rising rates of chronic diseases and physical or cognitive impairments, has dramatically increased the demand for long-term care (LTC). Most healthcare systems in Asian countries are ill-equipped to manage this escalating demand. In response to this challenge, family caregiving has become increasingly prominent.

In Asia, more than 80% of LTC is provided by family caregivers [4]. These caregivers play a crucial role, managing complex and physically demanding care for their family members throughout the illness trajectory. Their responsibilities include providing social and emotional support, collaborating with healthcare providers, ensuring compliance with medical routines, handling dietary requirements, and making critical medical decisions, such as on nursing home replacement, medical treatments, and end-of-life care [5]. Family caregivers are integral to shaping a sustainable LTC system in Asian countries [6]. While the aging population varies across Asia, most countries, particularly in East and Southeast Asia, are witnessing rapid growth in the number of family caregivers. The economic value of care services provided by family caregivers in six Asia countries is projected to reach $250 billion by 2035 [7]. However, the increasing demand for LTC poses acute challenges in these countries, where family members often bear the responsibility for caregiving [8]. Many governments face challenges in meeting the demand for LTC services, despite shifting care delivery toward local communities and households. Unlike Western countries, which have more established LTC policies, many Asian societies lack adequate policy support for LTC services. Although socioeconomic development, the maturity of LTC systems, healthcare policies, and population demographics vary across Asian countries, they share several common challenges. These encompass enhancing care quality, supporting family caregivers, and ensuring sustainable public funding for LTC services. There is a need for legislation and policies that emphasize the central role of the family and provide strong support to family caregivers [9].

Asia is one of the most rapidly aging regions in the world [10]. The trend toward smaller families, greater female workforce participation, increased adult mobility, and a declining proportion of working-age individuals has reduced the availability of family caregivers. This undermines the family's role as the primary source of care. Cultural norms in Asia provide both advantages and challenges for family caregivers. Research on filial piety, for example, has yielded mixed results. While some studies suggest that filial piety positively impacts the mental and physical well-being of family caregivers, others offer contradictory evidence [11, 12]. Asian family caregivers often face a “caregiving dilemma”. Cultural expectations drive them to continue caregiving, yet they may feel resentment due to the inescapable nature of their situation [13-15]. Caregiving exerts a profound impact on caregivers' lives, affecting employment, financial well-being, and social support networks, and often resulting in poor physical and mental health.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought attention to family caregiving, revealing the lack of recognition and undervaluation of unpaid family care in Asia [16]. During the pandemic, measures such as mask-wearing, hand hygiene, and movement restrictions coincided with increased unemployment, financial instability, and domestic violence. Lockdowns have affected access to primary and specialized health and social care services. Family caregivers of all ages have taken on a range of caregiving responsibilities, spanning personal self-care, emotional support, and financial assistance [17]. COVID-19 management strategies, including limitations on visits, caused many family caregivers to experience isolation and anxiety regarding the health of those they care for [18, 19]. The overestimation of family caregivers' confidence in using diverse communication methods, despite differences in demographics and technology skills, created a challenging cycle [20]. As a result, many caregivers found themselves trapped in social isolation, experiencing negative effects on their well-being, symptoms, and behaviors, while lacking adequate support in various aspects of their lives [21].

Despite increased awareness of the challenges faced by family caregivers, discussions related to caregiving predominantly remain within academic circles. It is fundamental for healthcare system to consistently highlight the need to support family caregivers to improve the quality of care. We have pinpointed four key focus areas for advancing research, practice, and policy regarding the role of family caregivers in Asian countries: (1) emphasizing family caregivers as sociocultural navigators in the healthcare system, (2) addressing the mental and physical health needs of family caregivers, (3) recognizing the diverse caregiving experiences across different cultural backgrounds, socioeconomic status, and countries of residence, and (4) strengthening the policy support for family caregivers.

2 EMPHASIZING FAMILY CAREGIVERS AS SOCIOCULTURAL NAVIGATORS IN THE HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

In Asian contexts, family caregivers play a significant role, yet their potential for collaborative clinical decision-making is often underutilized. Despite cultural variations in how healthcare professionals interact with older adults and their caregivers [15], studies consistently reveal a disconnect between desired and actual participation. Research shows that most family caregiver involvement is self-initiated, with healthcare providers not proactively addressing their preferred participation level [22]. This contrasts sharply with the wishes of both older adults and caregivers, who overwhelmingly appreciate and anticipate active participation in the decision-making process [6, 23]. Excluding caregivers from medical and long-term care decision-making raises ethical concerns and disregards the significant impact these decisions have on them, particularly considering the emotional burden they already carry. Therefore, adopting a more inclusive communication model within the healthcare system is crucial to facilitate effective family caregiver participation in decision-making processes.

Family caregivers play a crucial role in administering complex treatments, especially in outpatient settings. It is essential that all outpatient therapy recipients have a well-defined caregiver support plan. These caregivers are responsible for accompanying patients to daily visits, which may impact their ability to work, as they need to be available throughout the day and night. Encouraging family caregivers to take personal time while patients complete hospital visits is recommended. Despite the demanding nature of their tasks, formal support programs for family caregivers remain scarce. Recent research highlights the importance of caregiver well-being and collaborative relationships with healthcare professionals in ensuring positive outcomes for everyone [24, 25]. Indeed, some of the latest guidelines in Singapore, Japan, and Republic of Korea include assessing the burdens on family caregivers as part of the crucial outcomes for decision-making [26-28].

In Asia, family caregivers play a vital role in understanding and managing the social and cultural aspects of healthcare delivery for their older family members. For instance, younger family caregivers often assist in interpreting medical terminology, procedures, and paperwork when support staff are unavailable in healthcare settings. However, they may encounter challenges when translating cultural phrases or idioms within the healthcare context [23]. An illustrative example is that older generations' trust in herbal medicine sometimes leads to confusion when combined with Western medicine, resulting in polypharmacy issues [29]. Family caregivers serve as a crucial link, ensuring compatibility between cultural dietary practices and hospital service options. They may be responsible for interpreting their older parents' customs and practices to healthcare providers or assisting their parents in harmonizing healthcare norms and health-seeking behaviors [30].

Family caregivers in Asia are pivotal in several critical aspects of the care continuum. They navigate complex care decisions, provide unwavering support, and ensure dignified care for their loved ones across various stages of life. Family caregivers significantly influence nursing home placement decisions [31, 32]. They often collaborate with healthcare professionals to assess the individual's needs, evaluate available facilities, and make informed decisions about placement [33]. Family caregivers play an essential role in caring for persons with dementia. They provide daily assistance, manage medications, ensure safety, and offer emotional support [34]. During the end-of-life phase, family caregivers become the linchpin of support. They offer comfort, companionship, and practical assistance to their loved ones. Whether it is managing pain, facilitating communication, or ensuring a peaceful environment, family caregivers are there every step of the way. Their compassion and commitment make a profound difference during this sensitive time [35].

3 ADDRESSING THE MENTAL AND PHYSICAL HEALTH NEEDS OF FAMILY CAREGIVERS

The majority of family caregivers are female, working either part-time or full-time, and their caregiving work is typically unpaid. These caregivers often experience emotional and physical exhaustion due to the demands of their role and the concern for their loved ones. Additionally, their own healthcare needs may be overlooked as they prioritize caregiving responsibilities, such as maintaining a healthy lifestyle, seeking preventive care, and managing chronic illnesses through self-care. The physical and mental health of caregivers profoundly influences the quality of care they provide, directly affecting the quality of life of older adults. The caregiving stress process model, multiple role strain, and time scarcity offer mechanisms through which caregiving influences physical and mental health [36-38]. Studies conducted in Asia have reported poorer health outcomes for unpaid caregivers than non-caregivers, with the worst health and quality-of-life outcomes observed in caregivers of individuals with dementia and stroke [39]. Dementia caregivers are more prone to reporting decreased immunity, requiring more sick days, and experiencing more familial conflict [34]. Additionally, caregiving challenges encompass feelings of isolation, limited personal time, financial stress, lack of sleep, and reluctance to seek assistance. These challenges may lead to social seclusion, depression, and anxiety [40]. Cultural factors, including traditional norms related to filial duty, often prevent family caregivers in Asia from acknowledging the substantial caregiving responsibilities they shoulder. Consequently, this lack of recognition limits their utilization of available support services [41]. Many caregivers also report undiagnosed mental health challenges due to the absence of culturally and linguistically appropriate screening tools. Research indicates that caregivers in may express distress in culturally varied ways. For instance, individuals from East and Southeast Asia are more likely to experience mental health symptoms framed in somatic rather than psychological terms [42]. However, somatic symptoms such as insomnia, headaches, and fatigue are often omitted from standard depression and anxiety screening assessments [29].

At the same time, a growing body of research in Asia explores the positive aspects of the caregiving [43-45]. Highlighting these positive experiences, known as a “strength-based” approach, challenges the stereotype of caregiving as solely burdensome [46]. This perspective acknowledges the compassion, resilience, and family commitment that caregivers often display, recognizing their vital role in supporting the healthcare system's stability (Figure 1).

4 RECOGNIZING THE DIVERSE CAREGIVING EXPERIENCES

Asia is a vast region with diverse cultures, and while the importance of family caregiving is common across many Asian countries, significant differences exist in how caregiving is approached due to varying cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic factors. For example, cultural values such as filial piety (respect for older generations) in Confucian societies like China and Republic of Korea, or collectivism in Japan, heavily influence caregiving expectations [8]. Traditionally, multigenerational households were the norm, but the rise of nuclear families is altering caregiving dynamics [30, 47]. Historically, caregiving responsibilities often fell on daughters-in-law, though shifting gender norms are changing this [48]. Socioeconomic development also plays a role in caregiving practices. Wealthier nations such as Singapore and Japan offer more formal care options, such as assisted living facilities, which reduce the caregiving burden on families. Additionally, countries like Republic of Korea have implemented policies such as LTC insurance to financially support families [49]. In contrast, poorer countries may rely more heavily on family caregivers due to limited access to paid care services.

Family caregivers in Asia come from diverse backgrounds in terms of ethnicity, economic status, and family dynamics, leading to varying needs, stressors, and strengths. Despite this diversity, there is limited research that fully addresses the specific needs of different ethnic family caregiver groups, whether in urban or rural areas, or under various cultural circumstances. Certain subgroups, such as men, socially disadvantaged individuals, long-distance caregivers, and those caring for multiple family members, have not received sufficient research attention despite their increasing prevalence. A systematic review spanning from 2000 to 2022 highlighted that caregiving significantly impacts women's mental health, but research on men is sparse, even though they may face similar challenges [5]. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbate existing disparities, with higher COVID-19 fatality rates observed in marginalized and economically disadvantaged communities [50]. Social inequalities, such as poor living conditions, financial instability, and social isolation, significantly influence family caregivers experiences, determining whether caregiving becoming a challenging or beneficial cycle [24].

Understanding the distinct challenges faced by caregivers in rural and urban areas of Asia is also crucial. Rural regions tend to have a higher proportion of older adults and fewer available services, creating a heavier reliance on family caregivers [51, 52]. However, rural caregivers face significant challenges, including limited access to healthcare services, long-term care facilities, and community-based support. Migration to urban centers further reduces the availability of family caregivers in rural areas. As a result, rural caregivers often experience higher stress levels and poorer health outcomes compared to their urban counterparts, who may have more resources available [53, 54].

To enhance caregiving research across diverse populations in Asia, it is essential to adopt context-specific approaches. Further research must consider recruitment strategies that account for the type, timing, and intensity of caregiving. This could involve partnering with memory clinics and support groups to reach potential participants when they are seeking information or support. Researchers should also tailor research methods to minimize disruption to caregivers' daily routines, offering shorter surveys or in-home interviews. Furthermore, a condition-specific approach, such as focusing on caregivers of individuals with dementia or cancer, would allow for a deeper understanding of how different conditions impact caregiver well-being. For dementia, this allows researchers to explore the unique challenges caregivers face in managing behavioral changes, memory loss, and personal care needs [31, 34]. Geographic context is equally important. In rural areas, where caregivers often have limited access to support services, primary healthcare providers and home care teams are typically the first point of contact [25, 52, 54]. Researchers could collaborate with these teams to assess caregiver well-being and connect them with available support services, such as respite care or caregiver training programs. By adopting these strategies, caregiving research in Asia can move beyond generalities and provide a nuanced understanding of the unique challenges faced by diverse populations. Thus, in turn, will help develop targeted interventions that improve the well-being of both caregivers and the individuals they care for.

5 STRENGTHENING THE POLICY SUPPORT FOR FAMILY CAREGIVERS

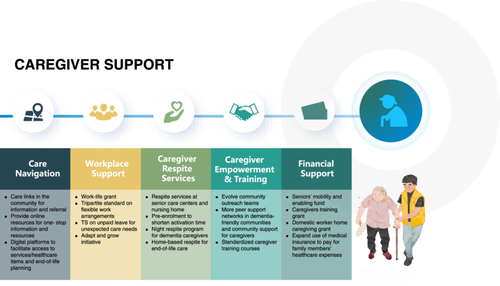

Although family caregiving is increasingly recognized in Asia, most countries still provide minimal policy support. Due to their caregiving responsibilities, many caregivers must forego career advancement or retire early, substantially impact their financial well-being. Public policies should address the needs of family caregivers by offering paid care leave, flexible work schedules, and antidiscrimination protections. In many Asian countries, care leave is less accessible than parental leave, despite being equally crucial for society functioning.

Recognizing the vital contributions of caregivers, several Asian countries have piloted legislative programs to offer crucial support [11, 55, 56]. Japan's Long-Term Care Insurance program provides financial assistance for professional care, reducing the hands-on burden on families. Republic of Korea's Family Care Leave grants employees paid time off to care for loved ones, lowering the risk of job loss. Singapore has implemented a multifaceted program that combines financial aid, training opportunities, and respite care services, empowering caregivers and offering temporary relief. China's National Basic Elderly Care Services establish minimum care standards for the older adults, including services like meal delivery and transportation, thus freeing up caregivers' time and energy for more emotionally demanding tasks. These varied approaches demonstrate a shared commitment to supporting caregivers and ensuring the well-being of both the caregivers and the older adults they assist.

Family caregivers are more likely to continue their roles when they feel appreciated. However, understanding best-practice policies in this domain is still limited, especially regarding the effective interventions to mitigate the impact of caregiving on employment and mental well-being. While cash benefits offer compensation and recognition for caregivers, they are not a complete solution. Although cash support acknowledges caregiver's contributions, it can also present challenges related to eligibility, ethical considerations, and policy trade-offs. It is crucial to view cash benefits within a broader care framework that includes caregiver training, work-life balance, flexible arrangements, and additional forms of support like respite care.

Emerging trends advocate for a holistic view of family caregivers, recognizing their diverse needs and personal aspirations beyond their caregiving duties [57]. Therefore, policies and programs should not only aim to alleviate the burdens of caregiving but also actively support caregivers' well-being and personal growth. While many Asian governments prioritize full employment and extended working lives, caregiving responsibilities often lead to early retirement. Current policies emphasize work as a sole productive activity, pushing caregiving into a secondary role. To address this, caregiving policies must take a person-centered approach, focusing on enabling caregivers to thrive as individuals while managing their caregiving responsibilities (Figure 2).

6 RECOMMENDATIONS

We offer several recommendations to better support family caregivers in Asia. First, leveraging awareness campaigns such as International Caregivers Day on November 26 can advocate for family caregiving policies. Within the healthcare system, it is essential for healthcare professionals to actively involve family caregivers in shared decision-making, recognizing their lived experiences and crucial roles in patient care. Second, empowering the healthcare workforce, including social workers, community health workers, nurses, and nutritionists, is critical to supporting family caregivers as sociocultural navigators. Enhancing patient-based health literacy across care teams is also key. Providing support through peer networks, family counseling, information sharing, and problem-solving is highly recommended. Third, mobile apps can be a valuable tool for managing caregiving tasks, scheduling telemedicine consultations, and providing emotional and logistic support for caregivers. These apps can offer specific guidance, educational resources, and connections to other caregivers, as well as link caregivers with support networks, including community resources and volunteers. Fourth, support groups and interventions for older adults and family caregivers should take cultural and social barriers in Asian countries into account. Designing culturally sensitive interventions that acknowledge these limitations is crucial. Close-knit support networks, particularly in single-caregiver households, can provide companionship, mutual support, information, and coaching. Investing in the development and expansion of community support programs for family caregivers is critical to enhancing their well-being and ensuring quality care for their loved ones. We also emphasize the importance of targeted mental health support for family caregivers, especially those who take on caregiving responsibilities at a young age. Lastly, future research should explore diverse approaches, such as individual and dyadic interviews, longitudinal surveys, and clinical trials, to improve research quality and ensure findings are applicable to practice and policy. It is important to translate psychological assessment tools not only into various languages but also in a culturally sensitive and valid manner, addressing the unique needs of family caregivers rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach.

7 CONCLUSIONS

In Asian cultures, the responsibility of caring for older family members is deeply ingrained. However, the challenges faced by family caregivers often remain unnoticed or unaddressed by society. Meeting the growing demands of LTC, requiring a collaborative, multi-sectorial approach involving individuals, communities, and governments. Policymakers and nongovernmental organizations must recognize the urgent need to address the shortcomings in institutional care and the lack of support for family caregivers. Prioritizing this issue on the policy agenda in Asia is crucial. Additionally, the diverse strengths of LTC systems across Asia offer valuable opportunities for cross-country learning and capacity-building.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Nan Jiang: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); resources (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (equal); writing—original draft (equal); writing—review and editing (equal). Bei Wu: Writing—review and editing (equal). Yan Li: Conceptualization (supporting); methodology (supporting); writing—original draft (supporting); writing—review and editing (equal).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

INFORMED CONSENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed.