Vaccine-breakthrough infection by the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant elicits broadly cross-reactive immune responses

Runhong Zhou, Kelvin Kai-Wang To and Qiaoli Peng made equal contributions.

After the World Health Organization (WHO) designated the omicron variant of concern (VOC) on the 26 November 2021, the extremely rapid spread of this variant is replacing the delta VOC with increased risk of vaccine-breakthrough infection in the South Africa, in European countries and in the United States.1 Both vaccine-induced neutralising antibodies (NAbs) and current NAbs in combination therapy have shown significantly reduced activities.2, 3 Till now, it remains unclear whether vaccine-induced memory responses can be recalled by the omicron viral infection. We, therefore, investigated the host immune responses in two cases of vaccine-breakthrough omicron infection in Hong Kong.

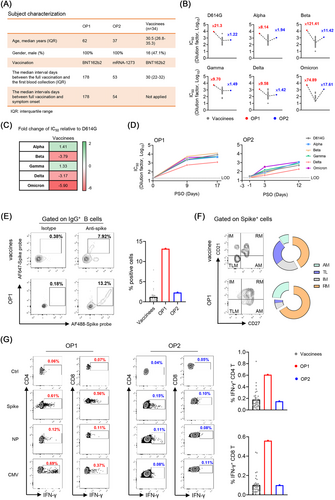

In mid-November 2021, the first Chinese case of omicron patient (OP1) was diagnosed in a quarantine hotel in Hong Kong.4 About 9 days after the OP1, omicron patient 2 (OP2), who was due to a separate transmission event, was also confirmed by sequencing analysis. Based on the vaccination records, OP1 and OP2 were confirmed with omicron infection at 178 and 53 days after the second dose of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273, respectively (Figure 1A). During hospitalisation, both cases presented with mild clinical symptoms not requiring oxygen supplementation or ICU treatment. With patients’ informed consent, we obtained three sequential sera and one peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples from each patient to determine their immune responses recalled by the omicron viral infection.

We first measured the neutralising antibody titre (IC50) in their serum samples against the current panel of SARS-CoV-2 VOC pseudoviruses, including alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P1), delta (B.1.617.2) and omicron (B.1.1.529) as compared with D614G (WT) (Figure 1B). We compared IC50 values of 34 local vaccinees, whose blood samples were collected around the mean 30 days after the second BNT162b2-vaccination (Pfizer–BioNTech) (Figure 1A).5 Consistent with recent preprint publications by others, we found that the omicron variant showed the greatest resistance to BNT162b2 vaccine-induced neutralisation with an average 5.9-fold deficit relative to D614G (Figure 1C). Strikingly, however, the breakthrough infection was able to elicit cross-reactive broadly neutralising antibodies (bNAbs) from the unmeasurable level (<1:20) to the mean IC50 value of 1:2929 (range 588.5–5508) at 9 days post symptoms onset (PSO) in OP1 and from the mean IC50 value of 1:24.3 to 1:854.5 at 12 days PSO in OP2, respectively (Figure 1D). Moreover, the amounts of NAbs in OP1 and OP2 were consistently higher than the mean IC50 values of BNT162b2 vaccinees across all VOCs tested (Figure 1B). In particular, there were 121.41- and 74.89-fold higher IC50 values against beta and omicron in OP1 than those in BNT162b2 vaccinees (Figure 1B). Besides NAbs against the current panel of VOCs, OP1 also displayed enhanced IC50 values of NAbs against 15/16 SARS-CoV-2 variants with individual mutations or deletions, including the E484K mutation, which conferred significant resistance to vaccine-induced NAbs (Figure S1). These results demonstrated that although the omicron VOC evaded BNT162b2 vaccine-induced NAbs, the breakthrough infection could recall cross-reactive bNAbs generally against all current VOCs in both OP1 and OP2.

Multicolour flow cytometry data showed no sign of severe immune suppression in OP1 and OP2 who had normal frequencies of T lymphocyte (no lymphocytopenia), stable conventional dendritic cell (cDC): plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) ratio and normal myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) similar to mild and healthy subjects, as we described previously (Figure S2).6 We also measured the frequency of Spike-specific IgG+ B cells, 13.2% in OP1 and 2.31% in OP2 were relatively higher than the mean 1.12% (range 0.004%–7.92%) found among BNT162b2 vaccinees around their peak responses (Figure 1E). Unlike SARS-CoV-2 infection in unvaccinated patients, who display predominantly tissue-like memory (TLM) B-cell response,7 Spike-specific IgG+ B cells from OP1 and OP2 exhibited the dominant phenotype of resting memory (RM) (Figure 1F), which was commonly found among healthy BNT162b2 vaccinees.

We further measured their cross-reactive T-cell responses to the Spike and nucleocapsid (NP) peptide pools derived from the SARS-CoV-2 wildtype as compared with BNT162b2 vaccinees by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS). The cytomegalovirus (CMV) pp65 peptide pool was used as a positive control. We found that Spike- and NP-specific CD4 IFN-γ responses were 0.61% and 0.12% in OP1 and 0.15% and 0.10% in OP2, respectively (Figure 1G). Spike- and NP-specific CD8 IFN-γ responses were 0.56% and 0.11% in OP1 and 0.10% and 0.08% in OP2, respectively. Moreover, the Spike-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses were relatively higher in OP1 or comparable in OP2 as compared with mean values in BNT162b2 vaccinees (CD4 T: mean 0.19% and CD8 T: mean 0.10%). As much weaker or unmeasurable T-cell responses were found in severe COVID-19 patients around the same period PSO,6, 8 T-cell responses in OP1 and OP2 probably also contributed to disease progression control.

As the omicron variant caused a higher rate of vaccine-breakthrough infection and reinfection than the delta variant,9 it is worrisome if such infections would lead to more severe sickness or death due to immune escape. In this study, we demonstrated that the omicron breakthrough infection rapidly recalled vaccine-induced memory bNAbs and T-cell immune responses, which very likely contributed to protection in OP1 and OP2. Our finding provides a probable immune mechanism underlying a recent report that most omicron patients had no signs of severe COVID-19 as compared with the delta variant.9 Our findings, therefore, re-emphasise the importance of complete vaccination coverage among human populations, especially in developing countries. Notably, the ongoing adaptive evolution of SARS-CoV-2 created an unprecedented demand of vaccines against VOCs.10 As similarly high amounts of bNAbs against both omicron and other VOCs were detected in OP1 and OP2, the rapid development of omicron-based vaccine is a reasonable strategy as a booster vaccine to elicit and sustain long-term cross-protective immunity against COVID-19.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council Collaborative Research Fund (C7156-20GF, C1134-20GF and C5110-20GF) and Health and Medical Research Fund (19181012); Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JSGG20200225151410198 and JCYJ20210324131610027); the Hong Kong Health@InnoHK, Innovation and Technology Commission; and the China National Program on Key Research Project (2020YFC0860600, 2020YFA0707500 and 2020YFA0707504); and donations from the Friends of Hope Education Fund. Z.C.’s team was also partly supported by the Hong Kong Theme-Based Research Scheme (T11-706/18-N and T11-709/21-N). We sincerely thank Drs. David D. Ho and Pengfei Wang for the expression plasmids encoding for D614 G, alpha and beta variants, and Dr. Linqi Zhang for the delta variant plasmid.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.