Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis presenting as transient ischemic attack

Abstract

Key clinical message

Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis may rarely present with TIA or stroke as an initial clinical manifestation. This case highlights the necessity of a broad differential and a high degree of suspicion for cardiac sarcoidosis in a patient with new neurologic symptoms and evidence of cardiac disease.

Cardiac sarcoidosis is a rare disease with a variety of clinical manifestations including heart failure and sudden death. Stroke as the earliest sign of disease has been described in rare cases. We present a case of a 54-year-old female with recurrent transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) of unknown etiology, initially in the absence of left ventricular dysfunction. Cardiomyopathy was later identified on echocardiography after a second TIA. Cardiac MRI was remarkable for focal left ventricular wall thinning with akinesis and dyskinesis of multiple wall segments, a right ventricular aneurysm, and diffuse myocardial late gadolinium enhancement. PET/CT showed multifocal areas of myocardial FDG uptake. At follow-up, echocardiography showed a left ventricular apical thrombus, in a previously identified thinned, akinetic region, suggesting cardioembolic origin for previous TIAs. She was started on anticoagulation therapy, prednisone, methotrexate, and adalimumab, with resolution of the thrombus and improvement in cardiac function. In conclusion, this case highlights the need to consider CS as a potential cause of cerebrovascular ischemic events in patients with few stroke risk factors but findings indicative of cardiac disease. It is essential to further explore the mechanisms behind these events and develop treatments that target their causes in this patient population.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown etiology characterized by the formation of noncaseating granulomas in various organs, including the lungs, skin, and the heart. Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is a rare manifestation of the disease, with an estimated prevalence of 5%–10% in patients with systemic sarcoidosis.1 When CS occurs in the absence of clinically apparent sarcoidosis elsewhere, it is considered isolated cardiac sarcoidosis (iCS). The prevalence of iCS among patients with CS is estimated to be around 25%.2 Clinical features of iCS depend on the location, extent, and activity of the disease, ranging from heart block and arrhythmias to sudden death. Patients with iCS tend to have poorer left ventricular systolic function at presentation and a higher incidence of ventricular tachycardia compared to those with CS and systemic disease.1, 2 Previous case reports have described stroke as a rare initial manifestation of CS in the presence of systemic disease.3-6 Only a few reports have described stroke in a patient with iCS which appears to differ in timing of presentation, diagnostic criteria, and clinical course.5 We present a case of isolated CS presenting as recurrent TIAs in a previously asymptomatic patient.

2 CASE PRESENTATION

A 54-year-old female with a past medical history of well-controlled hypertension, occasional premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), and a previous transient ischemic attack (TIA) presented with right-sided facial droop and incomprehensible speech. She was last seen at baseline health about 30 min prior. On arrival to the emergency room, physical exam revealed blood pressure of 145/92 mmHg, improving right facial paralysis, and a regular heart rhythm, with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. National institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 3 for partial facial paralysis and dysarthria with no other focal deficits. She returned to her baseline neurologically within an hour, to a NIHSS score of 0.

Five years prior, she was diagnosed with a TIA after presenting with a similar complaint of slurred speech. Workup at that time was unrevealing for embolic or non-embolic causes, the neurologic deficits resolved, and the cause remained unknown. Previous cardiac evaluation included a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) which revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 55% with no wall motion abnormalities and a negative microcavitation study. Ambulatory ECG monitoring at the time only showed a very small PVC burden (<1%) and was unrevealing for any other arrhythmias.

3 DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT

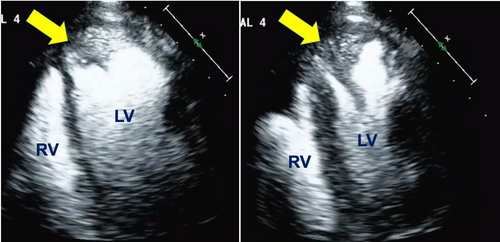

CT of the brain on arrival, in accordance with acute stroke protocol, did not show acute ischemic changes. CTA of the head and neck was then obtained, which showed no significant plaque, large vessel occlusions or stenosis. Given the negative CT findings, MRI of the brain was obtained which showed no evidence of hemorrhage, masses, restricted diffusion, or other acute intracranial pathology. An ECG showed sinus rhythm with a new RSR’ pattern in V1, consistent with right bundle branch block. The new conduction abnormality and concern for an embolic source for the TIA prompted a TTE, which showed a newly diagnosed cardiomyopathy with a LVEF of 40%, an abnormal global longitudinal strain of 12.8%, segmental wall motion abnormalities involving the apex, basal inferior and basal inferoseptal walls and swirling of contrast at the apex consistent with sluggish flow (Figure 1).

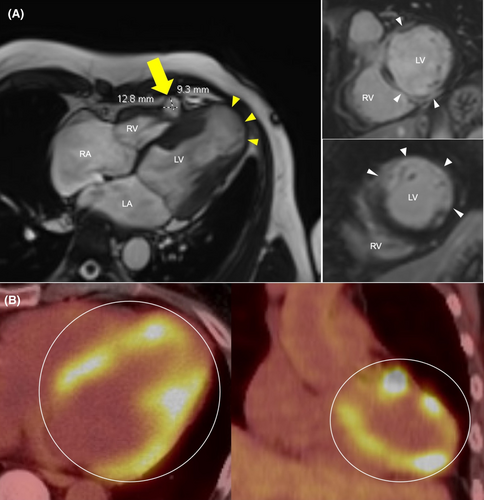

Given the newly identified cardiomyopathy on TTE, computed tomography angiography of the coronaries was obtained, which did not show any coronary stenosis. Additionally, there was homogenous enhancement of the left atrial appendage on early and delayed images consistent with no thrombus. To investigate for nonischemic causes of cardiomyopathy, a cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) was then obtained, which showed focal areas of thinning, akinesia and dyskinesia involving the left ventricular apex and several other wall segments, and diffuse areas of myocardial enhancement in a nonischemic pattern, concerning for infiltrative disease. In addition, a right ventricular pseudoaneurysm was identified, measuring 1.28 cm × 0.93 cm (Figure 2A). A fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography (FDG–PET) scan revealed multifocal patchy nodular areas of abnormal FDG uptake within the myocardium (Figure 2B). No additional areas of abnormal uptake were identified, including head, neck, and chest regions.

Considering the unexplained systolic dysfunction in the absence of coronary artery disease, no evidence of extracardiac disease but CMR and FDG-PET findings suggestive of CS, a diagnosis of iCS was favored. After discussion with pulmonary and rheumatologic services, therapy with prednisone 30 mg daily, oral methotrexate 7.5 mg once weekly, and 40 mg of subcutaneous adalimumab weekly were started. Repeat 48 h Holter showed a PVC burden of 3% including ventricular triplets, bigeminy, trigeminy and runs of accelerated idioventricular rhythm. Given these findings along with the CMR findings, an implantable cardioverter/defibrillator was placed.

4 FOLLOW-UP

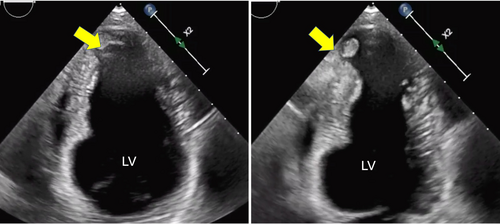

At her three-month follow-up visit, there were no recurrent TIAs. TTE redemonstrated wall motion abnormalities with a stable LVEF. However, a new left ventricular apical thrombus measuring 0.8 cm × 0.6 cm was found (Figure 3). The patient was immediately started on anticoagulation therapy with apixaban 5 mg twice daily. Further follow-up TTE 6 months later showed resolution of thrombus and mild improvement of EF to 45%, but redemonstrated sluggish flow. She was advised to continue anticoagulation therapy indefinitely. Over the following year, prednisone and methotrexate therapy were discontinued and she remained solely on maintenance with weekly adalimumab injections.

Follow up TTE a year later showed stable findings of known wall motion abnormalities and unchanged EF. The patient had no recurrence of cardiac or neurological events.

5 DISCUSSION

This case involves a 54-year-old female with well-controlled hypertension and a previous history of TIA, who presented with symptoms suggestive of a new TIA. Despite previous benign cardiovascular evaluations, her presentation led to identification of an underlying cardiomyopathy and characteristic imaging findings of CS. Neurological symptoms as initial clinical manifestation of CS are uncommon. This underscores the critical need for a thorough cardiovascular evaluation in patients presenting with recurrent TIA-like symptoms and evidence of cardiac pathology, especially when previous incidents remain etiologically unclear. In previously reported cases of stroke in CS, patients had known systemic disease and very few reports were in the setting of iCS.3-6 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of iCS presenting as recurrent TIAs.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that can affect any organ in the body, including the heart.1, 7, 8 Cardiac involvement may occur in up to 25% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis.7, 8 Most patients with clinically manifest CS, have minimal extracardiac disease, and up to one-third have iCS.7, 8 Symptoms, progression, and severity of CS vary widely. Some patients experience serious events such as arrhythmias, heart block, heart failure, and even death.7-9 Asymptomatic patients usually have a milder form of the disease, but sudden death can still be the first sign.9 iCS presents more frequently with cardiac dysfunction, is more associated with ventricular arrhythmias and has worse event-free survival compared with systemic sarcoidosis with CS. Therefore, this distinction may be of prognostic significance.2 Diagnosing and managing CS effectively requires careful and ongoing monitoring, even for those who show no symptoms.1, 2, 10

Cardioembolism was the most likely source for the TIA in our patient and in previously reported cases of stroke in CS.3-6 The mechanism of ischemic stroke in patients with CS is likely multifactorial and involves a combination of arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy resulting in blood flow stagnation, and a local inflammatory environment promoting intracardiac thrombus formation.11 While individually these factors may not solely cause ischemic events, their collective presence may facilitate the occurrence of cardioembolic phenomena.

In a report describing a case of ischemic stroke in a patient with CS and known systemic disease, thrombus pathology was consistent with a cardiogenic origin.3 In that case, the stroke was caused by a freshly developed thrombus originating from a left ventricular aneurysm in the presence of low EF. While our patient also had a ventricular aneurysm, the aneurysm was located on the right ventricle making it an unlikely source for stroke. In our patient, it is more likely that the apical akinesia, in combination with the inflammatory state of CS, promoted the formation of an apical thrombus. Similar to our case, a previous report of stroke in the setting of iCS, apical akinesia and a LV thrombus were identified as the likely cause for stroke.5 In a case series of eight patients with CS and ischemic stroke, a left ventricular apical thrombus was found in 50% of patients. This suggests apical thrombi may be an important etiology for cardioembolic stroke in CS, as observed in our patient.11

The diagnosis of iCS represents a true clinical challenge. Historically, established criteria for diagnosing CS, both from the consensus statement from the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous diseases (WASOG) required histopathologic demonstration of non-caseating epithelioid granulomas.9, 12 Although endomyocardial biopsy is highly specific for detecting CS, it is not very sensitive (<20% sensitivity) and is an invasive procedure. Pursuing a histologic diagnosis, thus, may delay early CS identification and initiation of treatment. However, in the 2019 update of the Japanese Cardiac Sarcoidosis (JCS) guidelines, the definition of iCS was established for the first time and alternative clinical criteria for diagnosis were included.13 After discarding systemic sarcoidosis, a clinical diagnosis of iCS may be established when four out of the five following criteria are met: (a) left ventricular contractile dysfunction (LVEF <50%), (b) the presence of high-grade atrioventricular block, (c) basal thinning of the ventricular septum or abnormal ventricular wall anatomy, (d) FDG PET reveals abnormally high tracer accumulation in the heart, and (e) gadolinium-enhanced MRI reveals delayed contrast enhancement of the myocardium.13 In our case, multimodality cardiac imaging with CMR was obtained to further evaluate for nonischemic causes of cardiomyopathy after TTE demonstrated LV systolic dysfunction. CMR was strongly suggestive of CS, showing focal areas of ventricular wall thinning and aneurysms, as well as focal LGE. Finally, the FDG-PET scan showed abnormal tracer uptake in the myocardium but no extra-cardiac uptake, suggesting isolated disease. Our patient met four of five major criteria for CS, and as such, iCS was diagnosed according to the JCS criteria and histologic diagnosis was not needed.

6 CONCLUSION

We present a case of iCS presenting clinically as TIAs. Workup on presentation led to a clinical diagnosis of iCS based on characteristic multimodality imaging findings. Identification of sluggish flow in the left ventricular apex led to the discovery of an apical left ventricular thrombus on subsequent imaging. This case highlights the importance of considering CS as a possible etiology of cerebrovascular ischemic events in patients with minimal risk factors and signs and symptoms suggestive of cardiac pathology. Further clarification of the mechanisms underlying ischemic events and the development of therapeutic approaches aimed at addressing the causes of these events in this patient group are necessary.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Moises A. Vasquez: Investigation; methodology; writing – original draft. Sharon Andrade-Bucknor: Conceptualization; supervision; validation; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was received for this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request of the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.