Unusual presentation of familial Mediterranean fever with co-existing polyarteritis nodosa and acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

Abstract

Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN) and polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) may occur simultaneously after streptococcal infection in a child who is previously healthy but carries a Mediterranean fever (MEFV) mutation. The homozygous M694V mutation in the MEFV gene may cause an augmented response to the streptococcal infection that plays a role in the development of both clinical manifestations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an autoinflammatory disease, associated with mutations in the Mediterranean fever (MEFV) gene with an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, and mainly affects populations of eastern Mediterranean descent.1 It is characterized by recurrent self-limited attacks of fever and serosal inflammation as well as the development of amyloidosis.1, 2 Patients with FMF may also have non-amyloid renal involvement including typical acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN).3 APSGN is an important non-suppurative, immunologically mediated complication of streptococcal infection4 and presents with the sudden onset of gross hematuria, edema, and hypertension with variable degrees of renal impairment.5 Vasculitic diseases such as polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) also affect the kidneys in FMF6. PAN is a primary multisystem inflammatory disorder characterized by acute necrotizing vasculitis of the small and medium-sized visceral arteries and their branches with a pauci-immune pattern,7, 8 and it may develop in children with FMF.7, 9 Here, we report a previously healthy patient, newly diagnosed with FMF and with co-existing APSGN and PAN.

2 CASE PRESENTATION

A 7-year-old Turkish girl was admitted to our hospital with fever, gross hematuria, abdominal pain, and myalgia for 4 days before admission. She had been taking ceftriaxone for 3 days on suspicion of a urinary tract infection, and there was a history of throat infection 2 weeks before. There were no recurrent attacks of fever, abdominal pain, arthralgia, or chest pain. Past medical history was unremarkable with no consanguinity. On admission, there were bilateral lower extremity pitting edema, generalized muscle tenderness, and abdominal tenderness with guarding on physical examination. She had no skin rash. The patient was in the >95th percentile for blood pressure (140/90 mmHg), and her body temperature was 38.7°C. Laboratory tests showed hemoglobin at 10 g/dl; white blood cells at 11,700/mm3; platelets at 352,000/mm3; C-reactive protein (CRP) at 185 mg/L; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) at 68 mm/hour; creatinine at 0.4 mg/dl; and albumin at 2.4 g/dl. Liver function tests and coagulation blood tests including prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and international normalized ration (INR) were normal. Urinalysis revealed 2210 red blood cells per high power field which were dysmorphic. The patient's 24-hour urine protein excretion was at the nephrotic level (1045 mg, 55 mg/m2/hour). Chest X-ray, echocardiography, and abdominopelvic and doppler ultrasounds were unremarkable. Viral serology, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, EBV, and cytomegalovirus, was negative. Complement component 3 (C3) was 48.3 mg/dl while complement component 4, anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) were normal. There was a significant increase in antistreptolysin O level (3886 IU/ml), suggesting group A Streptococcus (GAS) infection.

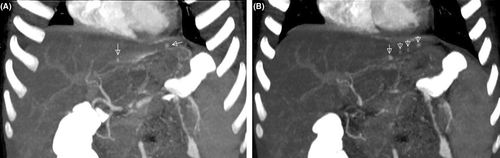

Based on these findings (a previous throat infection, hematuria, edema, hypertension, proteinuria, a fall in serum C3 levels, and elevated ASO titers), the patient was first diagnosed with APSGN. Hypervolemia and hypertension regressed with furosemide in addition to salt and fluid restriction. Since acute phase reactants were still high, and she had a resistant fever, antibiotic treatment was replaced with clindamycin. Subsequently, we suspected a co-existing vasculitic disease as we did not observe clinical improvement, and we therefore performed abdominal computed tomography (CT) angiography. The maximum intensity projection images obtained from the CT data showed multiple microaneurysms in the peripheral branches of the left hepatic artery compatible with medium-sized vessel vasculitis (Figure 1A,B). The abdominal aorta and the iliac, celiac, superior mesenteric, and both renal arteries were normal. These angiographic findings confirmed a diagnosis of PAN. Steroid treatment was initiated and three doses of pulse methylprednisolone (20 mg/kg/dose) followed by 2 mg/kg/day oral prednisolone were administered. Following the first pulse steroid dose, complaints dramatically reduced. CRP was 21 mg/L by the third dose, and C3 had returned to normal levels by the fourth week. There was no progressive decline in renal function, serum creatinine levels remained within normal ranges, and so, no renal biopsy was performed.

Since glomerulonephritis is not expected in PAN but both clinical conditions can be seen in FMF, we performed analysis of the MEFV gene that revealed a homozygous M694V mutation, and colchicine was started. Following clinical and laboratory remission, steroid treatment was gradually tapered and ceased at the 18th month. At 3 years follow-up, the patient continues with colchicine treatment only, is now wholly symptom free, and has normal laboratory parameters with no proteinuria.

3 DISCUSSION

We have described a rare presentation of FMF with co-existing systemic PAN and APSGN preceded by GAS following a throat infection. In PAN, arterioles, venules, and capillaries (including the glomerular capillary) are characteristically not involved.7, 8, 10 Unlike other systemic vasculitides which are idiopathic or autoimmune, PAN has several potential triggers including viruses, such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, cytomegalovirus, EBV, and Parvovirus B19, as well as bacteria.8 Patients with PAN may have a defect in handling streptococcal infections which can lead to the development of circulating immune complexes with arterial or glomerular damage.11

The diagnosis of childhood PAN requires histopathologic confirmation of necrotizing vasculitis or angiographic abnormalities as mandatory criteria,7 but because of the potential development of microaneurysms and hemorrhage, kidney, and liver biopsies should only be performed when other approaches have been unsuccessful.8 Necrotizing vasculitis can result in luminal arterial changes, observable by arteriography, and a diagnosis of PAN can be established in this way.8, 12, 13 The classical arteriographic finding is aneurysmal dilatation, but other luminal changes such as beaded tortuosity, abrupt cut-offs, tapering stenosis of smaller vessels, and pruning of the peripheral renal arterial tree may also suggest vasculitis.7

Liver involvement occurs in 16%–56% of patients, and clinical findings related to liver disease are rare. Necrotizing vasculitis may be seen in liver biopsy whereas hepatic arteriograms may show caliber changes with corkscrew vessels and distal microaneurysms.14 In the present case, the maximum intensity projection images obtained from CT angiography showing multiple microaneurysms in the peripheral branches of the left hepatic artery to confirm the PAN diagnosis. Treatment includes induction with high doses of corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide and maintenance therapy with low-dose prednisolone and azathioprine.7 In our patient, the abdominal aorta and iliac, celiac, superior mesenteric, and renal arteries were intact, and she responded dramatically to steroid treatment. We did not therefore administer cyclophosphamide or azathioprine.

As previously mentioned, capillaries are not involved in PAN, and so, glomerulonephritis is not expected in its course. On the other hand, however, patients with FMF may have non-amyloid renal involvement characterized by transient or persistent hematuria, proteinuria, typical APSGN, and various other types of glomerulonephritis.3 It has also been shown that vasculitic diseases such as PAN affect the kidney in FMF,6 and there is an association between PAN and FMF.6, 9, 15-17 Mutations in the MEFV gene may provide a basis for PAN development by forming a proinflammatory state and prompting an exaggerated response to streptococcal infections,9 and homozygosity of the M694V mutation has been found to be associated with the most serious phenotype in the clinical spectrum of FMF.18

4 CONCLUSION

This exceptional case constitutes a rare presentation of FMF with co-existing systemic PAN and APSGN. Since FMF is an autoinflammatory disease and streptococcal infections frequently trigger FMF attacks, all three conditions may be preceded by a streptococcal infection. The homozygous M694V mutation in our patient caused an augmented response to streptococcal antigens, leading to APSGN and PAN. This clinical presentation also confirmed the role of GAS in the etiology of systemic PAN.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YÖA, BED, and SAB were actively involved in the clinical care of the patient and wrote the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank the parents of the child in this case for their cooperation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article can be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.