Examining the Relationship between Antisocial Behavior and the Academic Performance of Teenagers: The Role of Schools and Causes of the Antisocial Behavior

Abstract

This research paper aimed to examine the academic performance of teenagers, the role of schools, and causes of the antisocial behavior. Our relationship between antisocial behavior and the sample consisted of 127 participants from different schools in the USA aged 13–15. A cross-sectional research design was used. We used primary data to conduct our research. The results suggested that there is a negative relation between antisocial behavior and the academic performance of teenagers. However, there was a significant difference between male and female students’ academic performance. Male children were involved more in antisocial behavior compared to female students. Therefore, we would like to recommend further research works that need to be done on this topic; teachers should closely monitor the behavior of their teenage students as these are the most vulnerable years in a kid’s life. Parents, teachers, and counselors must work together to implement modification strategies to help minimize teenagers’ behavioral problems. This will ultimately result in improving their behavior and also academic performance.

1. Introduction

This research aimed to find out the impact of antisocial behavior on the academics of teenagers, what role a school plays in the development of antisocial behavior in teenagers, and what are the causes of antisocial behavior. Teenage is considered a transition phase between childhood and adulthood. The cultural purpose of this age is to prepare a child for adulthood [1]. The phase involves numerous transitions including physical development, training, education, employment, and unemployment.

Teenagers with antisocial behavior usually exhibit behaviors like physical and verbal aggression, performance deficit, and social acquisition, which negatively impact both their potential to successfully establish peer relationships as well as adult relationships. Their behavior also tends to have a negative impact on their academic achievements [2].

As many studies suggest, the negative educational outcomes of teenagers with antisocial behavioral problems have been seen quite frequently. Students dealing with antisocial behavior get lower grades, probably fail classes, and experience higher school dropouts. Moreover, these poor results follow them even when they graduate high school and influence the rest of their lives [3]. Later on, when the children face adulthood, they experience negative employment, difficulties like drug and substance abuse, and a higher need for mental health checks and therapies. Despite differences in countries, from 2% to 20% of school-going children probably have antisocial behavior that has a huge effect on the lives of the young generation [4].

This particular study has been done to establish a relationship between antisocial behavior in teenagers and its effect on academics. Various factors lead to a child dropping out of schools and universities, and getting into low-paying jobs very early which also affects their future. It is very important to reach out to the root cause of the same and reach out to the authorities for the same [5]. Measures have to be taken to curb such practices, especially in developing or underdeveloped countries where usually children tend to give less importance to academics, and this is what this study highlights as well.

2. Objective

Antisocial behavior is negative and forces destructive action-showing characteristics such as overt and covert, deliberate aggression, and hostility toward individuals, places, and things. An individual with such behavior indulges in fights, theft, anger issues, no respect for social norms or others’ right, littering, underage drinking, verbal abuse, or manipulation. DSM-6 categorizes antisocial behavior under conduct disorder.

The reason for the development of such behavior is usually given shape by an unhealthy relationship of a child within a family, peers, community, and/or educational environment [6].

It is suggested that early biological precursors of later disruptive and violent behavior are set in action by stressors imposed by early physical vulnerabilities, such as genes, exposure to teratogenic chemicals, and an unfavorable caregiving environment. The issue is that because the findings are fragmented and frequently focus on a single biological system at a time with limited integration across systems, the basic underpinnings underlying antisocial conduct remain unexplained. Because most interventions with high-risk families to reduce antisocial behavior are started during later childhood or adolescence, an opportunity to intervene to prevent later antisocial conduct, based on these early signs, may be lost in early life [7–9].

Several studies have been conducted on adolescents’ antisocial behavior to understand the most vulnerable phase of one’s life and it is considered important as they are the building blocks of society. We conducted this research to establish a relationship between antisocial behavior and academics in teenagers and how educational institutions can help such behavior in them.

Students who exhibit antisocial behavior frequently engage in actions (such as verbal and physical hostility, social skill acquisition, and performance deficits) that have a detrimental effect on their capacity to successfully navigate relationships with peers and adults as well as their academic experience. Compared to average kids and students with other high-incidence disabilities, students who engage in antisocial behavior have lower marks, are less likely to pass classes, and have greater rates of school dropout [10–12].

The causes, nature, and effects of antisocial conduct in kids and teenagers are profiled in research on correlates of delinquency, including family etiologies and developmental pathways. Researchers have found that when children enter puberty, the emergence of antisocial behavior progresses from relatively insignificant indiscretions to more egregious manifestations of deviance. The characteristics of the most seriously delinquent young people are early onset along with increasing degradation toward more diversified and extreme antisocial activities.

3. Literature Review

“Student’s Participation in School and its Relationship with Antisocial Behavior, Academic Performance, and Adolescent Well-Being”

González et al. [13] conducted a study on students’ participation in school activities and their relationship with antisocial behavior, academic performance, and adolescent well-being. The study found evidence supporting that students’ participation had a significant role to play in life satisfaction. It was surveyed through a cross-sectional questionnaire (N = 791) from the Santiago location. The academic performance of children with antisocial behavior improves if they feel that the authority listens to them [13]. Better grades did not guarantee improvement in how they behaved. In the same way, if their suggestions are considered to modify the existing rules and regulations of their school, they tend to indulge less in antisocial behavior but their grades may or may not improve. The study helped us to understand different types of stimulation, provided for students’ participation give different outcomes. Psychologists, counselors, and teachers need to understand that to improve the behavior among adolescents, they should be involved in addressing the problems.

A group of activities that violate the established coexistence norms is known as antisocial behavior. A precise definition, however, has undergone modifications and development. Without reference standards, this meaning may also be unclear. Indeed, damaging the environment, people, or property as well as breaking social norms and expectations are all regarded as antisocial activities.

Antisocial behaviors typically start during childhood and adolescence and can take many different forms, such as aggressiveness, theft, vandalism, pyromania, and destruction of both public and private property. These actions can take place in a variety of settings, including the home, the community, and educational facilities. It may be directed at other students and other members of the school community, such as classmates, teachers, or staff, and is frequently seen in schools as a symptom of school violence. The destruction of school property, student absenteeism, or dropout are additional examples.

Previous research has shown a connection between depressive symptoms, especially in adolescents, and a high frequency of behavioral changes. According to Patterson et al. [5], “double failure hypothesis” model, interpersonal conflicts, and a lack of social skills, including those brought on by antisocial school behavior, can cause adolescents to be rejected by their environments and experience a number of adaptive failures appropriate to their age and educational level. Additionally, this lessens the encouragement and support of important others in helping teenagers deal with difficult life situations, making them more susceptible to developing mental health issues including depression and low self-esteem.

Various things can have an impact on a child’s or adolescent’s subjective well-being depending on the situation. Schools stand out among these because of the length of time children spend there and the significant life lessons they learn there. Within the school environment, significant relationships with students and teachers are formed, and they can serve as useful sources of support and well-being. Recent studies have emphasized the impact of schooling on the well-being of kids and teenagers. Varela et al. [14] investigated the link between life happiness and school violence in Chile and looked at possible underlying processes. The authors discovered that there was a school satisfaction-mediated indirect negative relationship between being a victim of school violence and life satisfaction. Additionally, engagement in school violence was negatively correlated with the school climate, indicating that a positive school climate may deter school violence by raising students’ academic satisfaction.

“Antisocial Behavior, Academic Failure, and School Climate”

Antisocial behavior, academic failure, and school climate: a critical review was conducted by McEvoy and Welker [15] and through their research, they found that the development of antisocial behavior in children begins with minor disobedience but slowly advances toward significant expression of deviance when they enter adolescence. They had conducted thorough research as to how antisocial behavior connects to academic failure and thus helped to formulate our study. Early onset along with increasing deterioration toward different and extreme antisocial behaviors is the characteristic of most serious delinquent youth.

They helped us to understand that the level of antisocial behavior and the level of learning are different from school to school and thus helped in our study. Both are related to the climate of the school which helps to shape the interaction among the students, teachers, parents, administrators, and the community [15]. A school climate is made up of the attitudes, norms, values, and beliefs, which underlie the level of academic achievement. It was seen that judgment of the teachers about students’ capabilities and teachers’ expectations about children’s performance influence affects students’ academic achievements.

“Prosocial and Antisocial Behavior in Preadolescence”

Children who engage in antisocial behavior in multiple contexts are more likely to continue doing so than those whose antisocial activities only take place in one. Similarly, youngsters who exhibit prosocial behavior in a variety of settings are more likely to continue doing so than those whose prosocial acts are situation-specific.

Teachers and parents differ from each other in a number of important ways, one of which is likely their capacity for comparing things. Teachers notice a wide range of pro- and antisocial behavior in their students. Most parents lack this knowledge. However, outside of the classroom, parents are more familiar with their children’s behavior. When parents and instructors are asked to report on their children’s pro- and antisocial behavior, these variations can easily lead to divergent scores. Multiple informants are therefore likely to provide a more comprehensive picture than a single informant [16].

There is evidence that some teenagers are prosocial sometimes but antisocial other times in research that used a person-centered approach. Such bistrategic children are generally well-adapted. According to her, this Machiavellian strategy involves striking a balance between “getting along” and “getting ahead.” Similar strong males were perceived as athletic, cool, and popular, but also as aggressive. Teachers and parents may reach quite diverse conclusions about a student’s traits when they are distinct enough to allow a firm assessment but not excessive. For roughly half of the kids, they do not agree. The cluster that was prosocial according to the parent but antisocial according to the teacher exhibits one of the most glaring contrasts. In order to more accurately account for social development, they suggested that it would be incomplete and distorted to describe the complexity of adolescents if one group of behaviors were studied without the other [16].

“Causes of Students’ Antisocial Behavior at Secondary Level Schools”

A study titled “causes of students’ antisocial behavior at secondary level schools” was done [17]. Their research concluded that teachers can play an important role in the course of students because they are in a position to offer assistance in improving the students’ behavior and suppressing negative behavior. A positive relationship between teachers and students presents scaffolding for normal social and behavioral skills. Peers’ actions can either result in prosocial or antisocial behavior among students as they spend plenty of time in the streets, classrooms, and schools [17]. The study assisted us in understanding the interaction among each other leads to their adoption of the same behavior and helped us to understand how the same children from one friend’s group were acting the same way. The involvement of parents at home as well as in school-related activities plays a huge role in modifying and reshaping the behavior of their children. The association of academically underachieving and socially outcast peers enhances deviant conduct in the absence of effective therapies and is the cornerstone of deviant clique structures and deviant subcultures. These aberrant subcultures provide normative norms for individuals who join, they serve to organize and guide deviant behavior, and they both model and encourage current and previous antisocial behavior in a variety of contexts.

“Neighborhood Contextual Factors and Early-Starting Antisocial Pathways”

The research was conducted [18] about neighborhood contextual factors and early starting antisocial pathways. It studied the hypothesis that the neighborhoods of a child may directly or/and interactively impact early-onset pathways. Their study considered various samples from different kinds of literature and helped us to understand the preadolescent stage of children starting to develop antisocial behavior through various surveys and questionnaires.

Earlier, the neighborhood factors were thought to be only indirectly related to the early beginning of antisocial behavior as most of their impact was through parenting. However, this research suggests that neighborhood constructs may be more directly associated with early-onset problems. That is to say, neighborhood factors like violence and danger, exposure to deviant peers, and economical disadvantages may actually “trigger” or at least increase the risk of serious delinquency. Thus, psychological, sociological, and ethnographic researches were presented to examine the relationship between neighborhood constructs and antisocial behavior [18]. The research had mixed results. It looked that neighborhood contextual factors associated with early onset of antisocial behavior in complicated ways were based on the concepts and measures of these variables while other individual and family-based variables also had to be considered.

“Leisure Activities and Antisocial Behavior for Adolescents”

The most convincing proof of a decrease in antisocial conduct is seen in longitudinal analyses of adolescent leisure activity participation and adjustment. The ability to participate in numerous community activities that were organized by highly qualified adults was a key intervention component. The results showed that among the young people who took part, there were significantly decreased levels of hostility and antisocial behavior. Youth leisure activities have been associated with an increase in antisocial conduct and have been conceptualized as “attractive diversions” from school and other intellectual endeavors. They have also been implicated as being the cause of peer rejection and exclusion based on socioeconomic status [19].

Offending patterns are described as offending trajectories, which vary according to developmental processes. Therefore, distinct offending trajectories capture the distinctive impact of many known and unknown explanatory variables for each group of trajectories. It is increasingly obvious that not all young people who commit juvenile offenses have the same developmental trajectory; variances in developmental trajectories are crucial to comprehend the causes of juvenile offending [20]. Based on this fact, we predict that juveniles who share an offending trajectory will have substantially more comparability on a wide range of background characteristics than youths who have separate offending trajectories.

Sports sponsored by schools and communities, music ensembles, and church groups are a few examples of highly regimented activities. The majority of youth leisure activities, in contrast, are highly unstructured, lack official guidelines or adult leaders, and have few objectives that are tied to skill development (e.g., watching television, or hanging out with peers). To some extent, all teenagers partake in these unstructured leisure activities. As a result, there might not be a strong link between deviance and unstructured activity. However, compared to highly structured leisure activities, unstructured leisure activities offer more potential for antisocial conduct [19].

Unstructured recreational activities may provide the perfect environment for starting, continuing, and accelerating antisocial conduct, particularly if the social context of the activity contains a significant percentage of deviant peers.

“Young students at risk for antisocial behavior: The utility of academic and social skills interventions”

When schools try to help adolescents with externalizing behavior patterns, they face a serious conundrum. Many problems and behaviors lead to this conundrum. First, many kids with behavior disorders go undiagnosed and, as a result, unserved throughout the early years of their educational careers because the educational system takes a reactive approach to dealing with behavior problems and because there is a lack of definitional clarity. The provision of services to students who exhibit antisocial behavior patterns is frequently postponed until a learning disability is discovered or clear signs of serious underachievement emerge. Second, studies have shown that as kids get older, they become much more resistant to assistance.

Early, efficient, and effective solutions that address behavioral and academic issues must be found. Since research on best practices has shown that parent education and training is an efficient intervention technique, it is ideal that these treatments involve the parents. Unfortunately, parent participation in training programs is not always possible because antisocial behavior patterns are frequently passed down through generations. In these situations, the school will bear the primary obligation for intervention [21].

Students who are unable to complete the assigned duties may act out to avoid them. Academic skill deficits would be the ideal target behaviors for rehabilitation if this causal model of behavior problem development is correct. According to the second causal paradigm, externalizing practices result in poor academic performance. Students are more prone to miss out on important academic material if they are not academically engaged due to involvement in other disruptive nonacademic activities. If this causal hypothesis is accurate, the best therapies would concentrate on reducing problematic behaviors [21]. Finally, it is possible that externalizing behavior and underachievement have a transactional relationship. If both of these factors act in concert, an intervention aimed at improving academic skill deficiencies and problematic behaviors would be required.

“Male antisocial behavior in adolescence and beyond”

When they were young, LCP males exhibited higher than average levels of risk in the areas of parenting, neurocognitive growth, and temperament/behavior (panel b, left). The only risk factor for which AL boys had higher scores than the cohort average was teenage peer misbehavior. According to personality tests, LCP boys were impulsive, angry, alienated, skeptical, cynical, and have a callous and cold attitude toward people [22]. His personality was in stark contrast to that of the AL lads, who had unusual ideals and were willing to dominate others to advance (such as approval of drug legalization). According to personality tests, AL boys preferred close relationships over LCP boys. LCP men were 2.5 times more likely than AL men to have been convicted of an adult crime by the time they were in their late 20s.

“Fostering academic competence in Latinx youth: The role of cultural values and parenting behaviors”

Structured teams and organizations draw kids with a range of social and intellectual aptitudes. Participating in the activity gives teenagers with low or marginal competence the chance to develop relationships with peers who are more competent than they are. Structured activities can impose organization on adolescents’ free time, which may enhance parental monitoring techniques and trust by enhancing parental awareness of the adolescent’s whereabouts, activities, and companions. Additionally, parents and other adults may be more likely to encourage their children to participate in organized leisure activities by being involved themselves or by providing assistance [23].

In contrast, low-structure activities frequently lack traditional social interactions, and some unstructured leisure activities seem to be predominately participated in by troubled teenagers. Youth may be at risk for antisocial conduct in unstructured leisure activity environments through social influence to the extent that exposure to deviant youth augments behavior problems. Due to the irregularity of meetings and the nature of the social associates involved in such activities, regular participation in unstructured leisure activities may impede parental monitoring attempts and reduce parental knowledge and trust in children’s leisure activities.

“Adolescents’ antisocial behavior and their academic performance: The case of high schools in Jimma town”

Low academic achievement leads to a loss of self-esteem, low commitment to school, and frustration, which in turn, results in delinquency and antisocial behavior. That means underachievement leads to problematic behavior. Not only this, problem behavior heralds and causes underachievement. That means, the amount of time children is engaged in meaningful learning activities is reduced due to their time spent acting out or being disciplined for aggressive behavior [24]. Additionally, aggressive children may also develop negative relationships with teachers and peers or negative feelings about school, and as a consequence be less inclined to exert effort on academic work.

4. Research Questions

-

(RQ1) What is the impact of antisocial behavior on academics in teenagers?

-

(RQ2) What is the role of schools in antisocial behavior in teenagers?

-

(RQ3) What are the root causes of antisocial behavior?

5. Methodology

Research method: We used different types of research methods to carry out this research. Quantitative analysis was implied to know the impact of antisocial behavior on academics and the educational-related causes of such behavior in teenagers. The state of Delaware in the United States of America (USA) was chosen by us to conduct our study. We specifically chose the USA because antisocial behavior is more prevalent in Western countries or cultures. This may be due to several factors such as the individualistic cultures these countries follow; children are independent and low cohesiveness among the family members. Delaware is among the Middle Atlantic states located on the Northeastern part of the Delmarva Peninsula in the USA. The data were collected through email and telephone interviews.

Participants: We got in touch with the head of the administration of 15 private schools in Delaware. We received the email ids of teachers who taught teenagers and got a sample of 170 students from these 15 schools. Out of 170, 96 were boys and 74 were girls and their ages ranged from 13 to 15. It is worth noting that to meet the ethical requirements, the researchers earned the participants’ consent. For this purpose, before running the main study, the participants’ parents who were willing to participate in the study signed written consent and submitted them to the researchers.

Data collection: On average, three to four teachers volunteered to fill out our checklist.

An agreement was signed by the participant’s parents, which guaranteed the nondisclosure of the students, the participants; and the schools’ names. The participants gave full consent to the conditions of the agreement as set mutually by both parties. It was a simple checklist with 10 questions where a teacher just had to mark yes or no to get in-depth information about the children. This was a subjective interview where we asked different questions from different teachers. However, a set of basic questions was asked to all of them, enlisted below.

- (i)

Do the students get angry quickly?

- (ii)

Are the children often absent from school?

- (iii)

Do the children hit others frequently?

- (iv)

Are the children unable to control their temper?

- (v)

Do they use abusive terms with their peers?

- (vi)

Do they deliberately disobey authority?

- (vii)

Do they feel better after the hitting?

- (viii)

Do they indulge in stealing?

- (ix)

Is truancy common for them?

- (x)

Do they harm the school property?

- (xi)

Are their parents aware of their behavior?

- (i)

Gender of the student

- (ii)

Do they get distracted in all the classes or some classes?

- (iii)

How is their academic performance?

- (iv)

What kind of relationships do they have with their peers?

- (v)

Do they behave in the same way at the home too?

- (vi)

What triggers their behavior?

6. Results and Discussion

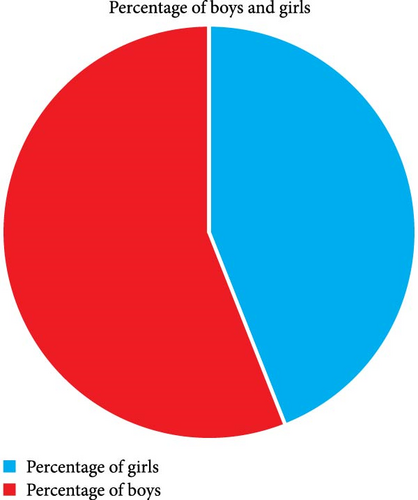

Our sample consisted of 127 children from 15 schools in Delaware, USA. The number of boys to girls who had antisocial behavior in our sample is shown in Figure 1.

Assault, theft, and fraud are just a few of the various ways that antisocial behavior can appear, and these manifestations might alter over time. Antisocial conduct has a metamorphic element, which begs the question of how such disparate actions are related to one another and what fundamental characteristics or functions underlie the diversity of behaviors.

During the juvenile years, disruptive, antisocial, and delinquent conduct can refer to a wide range of potential behaviors that might vary in severity and in terms of whether or not criminal laws are broken. Disruptive conduct is the term used to describe children’s enduring negative emotional behavior patterns, including tantrums, persistent oppositional behavior, and challenging temperament in newborns. Typically, persistently disruptive child behaviors often elicit negative responses from peers or caregivers such as anger, impatience, punishment, or even avoidance [25].

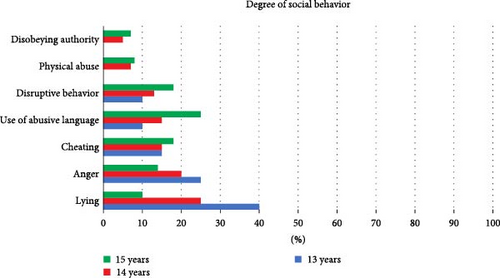

The most common form of antisocial behavior and to least common are shown in Figure 2.

- (1)

Lying

- (2)

Anger

- (3)

Cheating

- (4)

Use of abusive language

- (5)

Disruptive behavior

- (6)

Physical abuse

- (7)

Disobeying authority (inside as well as outside school).

Figure 2 shows the degree of antisocial behavior. We can interpret that 40% of 13-year-old children were lying, 20% of them showed aggression, 15% of children were cheating, 10% of them were using abusive language, and the same percentage of children showed disruptive behavior. However, no child from our sample in this age group was involved in physical abuse and disobeying authority. We can say that they were mildly antisocial.

Again, we can see that 25% of the children aged 14 were lying and 20% of them showed aggressive behavior. There was no change in the percentage of children who cheated at the age of 13 and 14. Twelve percent of children showed disruptive behavior. Very few, i.e., <10% of children indulged in extreme forms of antisocial behavior like physical abuse and disobeying authority.

With age, the symptoms of antisocial behavior changed, and it became severe. It is very clear from the given graph as only 10% of children of 15 years were lying. The number of children who cheated increased as it is 18%. Twenty-eight percent of children were using abusive language and 12% showed disruptive behavior. The children tended to physically abuse others and disobey the authorities as 8% of the children were involved in both.

Each classroom has established regulations that specify how pupils will be graded and how praise or gold stars will be awarded. Students try to accumulate as many points (rewards) as they can under this system, which has been likened to a game, although a serious one. A wide range of incentives are available, including positive reinforcers, which can range from the internalized satisfaction of having done one’s best (which supports learning goals) to public recognition for doing better than others (reinforcing performance goals) or at least being praised for playing by the rules, which supports prosocial behaviors like deference to authority figures and a willingness to put forth effort. Additionally, there are many negative reinforcers for disregarding a work ethic, from the prospect of failing grades to instructor warnings and the forced isolation of rule breakers. Therefore, in addition to being mediated by cognitive mechanisms, the causal relationships between accomplishment goals and future academic performance are also influenced by the incentive structures in place in the classroom. In recent years, two incentive schemes have been the focus of extensive investigation [26].

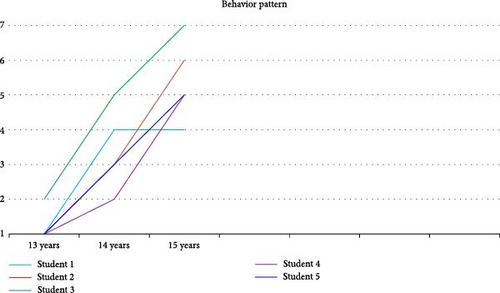

We took a random sample of five students and asked the teachers about the degree of rise in their antisocial behavior (Figure 3).

Our results were based on the checklist we sent to the teachers where they just had to mark yes or no, the basic set of questions we asked them over our telephone interview, and the questions we further asked them. Our first finding shows that antisocial behavior is more prevalent in boys than girls, which resonates with earlier studies conducted on antisocial behavior in teenagers as well, where gender difference was the focus [27]. As our sample consisted of children aged 13–15, only a few were involved in extreme types of antisocial behavior like truancy and substance abuse. Lying is the most common type of antisocial behavior as mentioned above. This research aimed to study the impact of such behavior on academics in teenagers and how schools play a role in antisocial behavior in teenagers.

In this research, we found a negative relationship exists between antisocial behavior and academics. Teenagers dealing with antisocial behavior get lower grades, and due to their aggressive attitude, they also tend to drop out of school and engage in earning money. This finding has been justified by research works on antisocial behavior engaging children to take impulsive and wrong decisions [28]. The teenagers who do not perform adequately at school are probably involved more with substance abuse, smoking, drinking, and drugs; those involved in risky behavior also tend to have low academic performance.

It has been observed that antisocial behavior limits the chances of meaningful academic achievements. As it is known that teenage is a very crucial time when children face changes, puberty is seen affecting them [29]. Absenteeism, which is a common characteristic of antisocial behavior, reflects more in teenagers due to the changes they confront. Absenteeism is not good for their academic achievements, self-esteem, promotion, etc. because they fall behind their counterparts in the same class. This increases their probability of dropping out of school [30].

Aggression, violence, delinquency, etc. are externalizing behaviors. These are typical characteristics of most antisocial teenagers. These tend to be more stable over the years, more defiant to intervention, and as a result are challenged by a worse diagnosis for treatment. Teenagers with such behavior patterns function at lower levels in academics, cognitive, and social areas [6].

Regarding the gender gap in antisocial conduct and academic achievement, men were shown to be more likely than women to engage in antisocial behavior in this study. This gender disparity shows that the male sex is related to characteristics that are either biologically, psychosocially, or both etiologically responsible for a significant portion of antisocial conduct. For instance, there might be sex-specific genes impacting antisocial behavior or environmental factors that only affect men that cause antisocial behavior. Alternately, it is possible that both sexes share all of the same risk factors for antisocial conduct, but that males are more likely than girls to experience these risk factors or are more susceptible to them.

Antisocial teenagers are also characterized by below-average academic performance, acquisition deficits in academics, and low rates of academic engagement. So, they become the most challenging to deal with [31, 32]. Taking into account how the environment impacts the behavior of teenagers, it is commonly evident that schools can either foster or inhibit abusive traits. Researchers in this area try to find out how the “personality” of a school contributes to such behavior in teenagers [33]. Every school has its personality just like an individual. Our research found out that effective schools have a positive impact on teenagers irrespective of their home conditions, social status, gender, race, and ethnicity [34].

School climates that are known to foster antisocial behavior have low expectations for excellence, lack commitment to building students’ efficacy, and inefficient administration. Such schools encourage antisocial behavior in their children as well as witness more academic failures [35]. Teenagers who tend to face repeated failures in academics and also cocurricular activities may lead to a tainted self-image which will probably decrease their dedication to student roles, reduce their motivation to do good academically and they become more alienated from school [36].

Teenagers who struggle academically are more prone to engage in risky behavior, and those who do so will see a decline in their academic performance. Therefore, it becomes crucial to comprehend how to mitigate the impacts of risky conduct on learning outcomes. However, the association between conduct and academic achievement was shown to be quite low in China Habin’s study, whereas it is highly significant in this one. This may be explained by cultural influences and other local variations in components. Finally, scholars have also suggested that two key indices of success for school-age children should be excellent academic achievement and behavioral competence.

Regarding gender differences in antisocial and academic performance, boys engage more in such behavior than girls which was quite evident from our sample. The difference suggests the reason/s behind this are either biological or psychological or both [37]. Academic failures bring with them a loss of self-esteem and school alienation. Alienated and uncommitted teenagers are probably seen negatively by peers and teachers. They become prime targets for involvement in peer groups of other antisocial and alienated teenagers, trying to get support for their behavior [24].

Next, we researched the factor behind the antisocial behavior of teenagers. The factors were divided into three categories namely family, socioeconomic status, and peers.

Boys were seen to have greater indications of antisocial conduct at both ages 13–14 and 16–17, which is a well-known sex difference. Girls had a larger heritability of antisocial conduct at ages 13–14 and 16–17 than boys, but there were no gender differences in the three psychopathic personality traits.

Family support includes actions like love, nurturance, empathy, guidance, information, acceptance, and material support. All these have a big influence on teenage behavior. Lack of family involvement, low level of a parent–child relationship, and family negligence act as the building blocks of antisocial behavior [38, 39].

The relationship of parents with their children and the background of a family are the most important reasons for aggressive behavior. Domestic problems play a huge role in the behavior of a child. An unstable or disturbed home environment and regular clashes between family members hurt their mindset.

Socioeconomic status includes parents’ education, parental income, and family occupation. This allows us to get a fair idea about the social, financial, and human capital of any family. It is a significant indicator that influences antisocial behavior in teenagers. The influence of peers on a teenager’s behavior cannot be denied. The involvement of peers with their deviant peers increases the probability of such behavior. Antisocial teenagers choose like-minded folks as their playmates [20]. The other side of the coin is that aggressive children are rejected by their peers. This rejection becomes a major reason to bond with like-minded people. Later on, in their lives, this bond can lead to gang memberships as well.

Recently, the significance of simultaneously examining prosocial and antisocial conduct has been emphasized because it is debatable whether examining one will necessarily reveal information about the other. We specifically considered the possibility that kids might behave antisocially according to one informant and prosocially according to another as we discussed the concurrent research of pro- and antisocial conduct.

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

We concluded from the study that a negative impact falls on the student’s academic performances if they possess antisocial behavior. We also dug through the causes for having antisocial behavior and it took us to the problems or behavior in the family. Usually, a family having a low socioeconomic background will frequently be dealing with monetary problems, which would lead to the child being forced into working from a younger age to bring in the flow of cash. It might also happen that frequent fights among family members encourage the children to indulge in rude behavior which they might feel is something correct to do. Stealing is something that a child would do when they are not fulfilled with their needs, and that is what we exactly got to understand from our survey. Antisocial behavior in teenagers has become one of the biggest hurdles to their adjustment in schools, peers, family, and society. Their negative and disruptive activities/actions indicate maladjustment. Therefore, the present research was an endeavor from our side to find out the impact of such behavior on academics in teenagers and the role of schools in it. It also has a negative relationship with academics. This means that when the abusive behavior starts to show more frequently, academic performance decreases.

- (i)

Teacher training

- (i)

School environment

- (i)

Further research

Research is needed to build effective interventions. Further research is needed to understand student–teacher relationships so our future teachers know the skills they need to help them in the classroom.

- (i)

The study was done with a small sample, and the reverts that were given by the tutors of the sample schools were very less.

- (ii)

Very few teachers were counselors who could give out half-hearted information due to the nondisclosure agreement between the patient and doctor but with the information, our implications could be derived.

- (iii)

The research was done based on teenagers but the age bracket taken was only 13–15, the research can be extended with this domain and a more authentic data set can be achieved.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of private schools in Delaware (No. 1156235-201637-219-06).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.