WHO Reporting System for Lung Cytopathology: Insights Into the Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-Diagnostic, Atypical and Suspicious for Malignancy Categories and How to Use Them

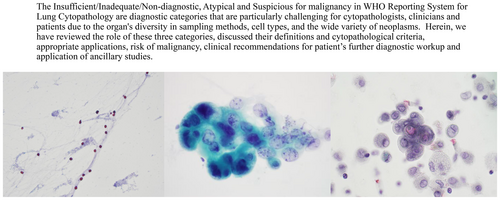

ABSTRACT

The World Health Organization Reporting System for Lung Cytopathology (WHO System) is an international effort aiming to serve patients worldwide in all medical resource settings and improve patient care globally. It is an evidence-based standardised reporting system applicable to all respiratory cytopathology specimens. The WHO System consists of five diagnostic categories including Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic, Benign, Atypical, Suspicious for malignancy and Malignant. Each category has an associated risk of malignancy established from the current literature and recommendations for further management to establish as precise a diagnosis as possible. The key diagnostic cytopathological criteria for each entity are established, a differential diagnosis based on cytopathological features that is globally applicable is discussed, and best practices in appropriate ancillary studies are presented. The Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic, Atypical and Suspicious for malignancy are diagnostic categories that are particularly challenging for cytopathologists and clinicians and patients due to the organ's diversity in sampling methods, cell types and the wide variety of neoplasms. Herein, we have reviewed the role of these three categories, discussed their definitions and cytopathological criteria, appropriate applications, risk of malignancy, clinical recommendations for patient's further diagnostic workup and application of ancillary studies. The aim was to increase cytopathologists and clinicians understanding of the three categories and provide a framework for the essential discussions that should follow.

Graphical Abstract

The WHO System is an international effort to standardise category definitions, establish the key diagnostic cytopathological features of entities of the lung, propose the best use of ancillary tests in lung specimens, encourage the use of standardised pathology reports containing essential components in an integrated report and propose estimates of the risk stratification for each diagnostic category based on the current literature, and recommend further diagnostic management. The ultimate aim was to improve patient care globally regardless of the available local medical resources by creating a common language between cytopathologists and clinicians, but the Inadequate/Insufficient/Non-diagnostic, Atypical and Suspicious for malignancy categories can often lead to miscommunication or frustration. There has to be clear discussion between pathologist and clinician because these categories frequently require additional cytopathological evaluation, CNB, appropriate ancillary tests and discussion in tumour boards whenever available to establish a specific diagnosis.

Insufficient, Atypical and Suspicious for malignancy categories in the WHO system for lung cytology are challenging. The clinician's expertise in obtaining specimens, the cytopathologist's diagnostic skill, the lesion's size, site and characteristics, ROSE access, specimen triaging and preparation techniques, ancillary tests and CNB are contributing factors.

1 Introduction

The landscape of pulmonary cytopathology is complex. Advancements in imaging technologies have markedly enhanced the detection of pulmonary masses and nodules, playing a critical role in both diagnosing and staging lung cancer. Notably, approximately 70% of lung cancers present at an advanced stage and are deemed inoperable or metastatic at the time of diagnosis, positioning cytopathology as a crucial first-line diagnostic tool within the diagnostic tissue algorithm for lung cancer [1]. Pulmonary cytopathology is challenging with multiple methods of specimen collection, variations in anatomical sites including peripheral, peribronchial and central that affect accessibility, and variations in size, cellular components and concepts of specimen adequacy for different specimen types.

Endobronchial ultrasound-guided (EBUS) fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is a routinely performed procedure to evaluate the nature of central lung nodules. Ancillary studies such as immunocytochemistry are performed to enhance and, in many cases, provide a definitive diagnosis whenever the cytomorphology is challenging [2, 3], and molecular studies, particularly next-generation sequencing (NGS), are routinely required in non-small cell lung carcinoma cases. Given the advanced stage at which lung cancer often presents and the limited availability of surgical specimens, diagnosis largely relies on cytopathological findings and materials, such as cell blocks, complemented by core needle biopsies (CNB) when feasible, to achieve specific diagnoses that guide therapeutic strategies. Therefore, a pulmonary cytopathology report should use standardised terminology, a standardised descriptive language and provide as specific and accurate a diagnosis as possible in a cytopathology report that integrates cytopathological, immunocytochemistry (ICC) and NGS findings in a format that includes these components. The exact format will vary based on the local laboratory information systems and established practices. This integrated report is crucial for the management of patients with a lung nodule/mass with or without suspicious imaging findings where the nature of the nodule requires clarification through cytopathology biopsy techniques.

The need for a structured reporting system with hierarchical categories has driven the development of a universal reporting system in lung cytopathology, the WHO System, which aims to standardise diagnostic reporting and improve clinical outcomes worldwide.

The journey to establish a standardised reporting system for lung cytology commenced in 1999 with the publication of the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology (PSC) guidelines [4]. Although these initial guidelines set a precedent, their global adoption was very uneven, leading to significant updates in 2016 [5, 6] and again in 2019 [7]. The Japan Lung Cancer Society and Japanese Society of Clinical Cytology system was released in 2020 [8]. These efforts aimed to standardise terminology with tiered classification systems to better align cytopathologists and pathologists with clinicians for a more unified approach in managing patient care. The revisions offered detailed outlines of specific diagnostic categories, anticipated risk of malignancy (ROM) rates and suggested management of the patient in terms of recommendations for further diagnostic workup.

The International Academy of Cytology (IAC) has collaborated with the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which is the organisation of the WHO that has the role of developing and promulgating multiple editions of the Classification of Tumours (the ‘blue books’, to develop a specialised series of WHO reporting systems [9] for cytopathology including lung cytopathology. The primary aim of this collaboration is to establish universal standardised reporting systems that have standardised terminology and establish by international consensus the key diagnostic cytopathological criteria for entities to ensure robust cytopathological diagnoses globally, including accommodating and supporting laboratories with limited resources in low- and middle-income countries [10].

The WHO System was published in 2022 [10, 11], and is the first international, evidence-based reporting system designed to serve all patients globally. The WHO System provides a structured reporting system for standardised reporting of lung cytopathology both exfoliative and FNAB specimens, that facilitates communication between cytopathologists and clinicians with the fundamental aim of improving patient care [9]. The WHO System includes five diagnostic categories—Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic, Benign, Atypical, Suspicious for malignancy, and Malignant—each with an associated ROM and tailored recommendations for further diagnostic and clinical management [12, 13]. These categories are defined and detailed in separate chapters, and entities in the Benign and Malignant categories are presented as to their key diagnostic cytopathological criteria, their cytopathological differential diagnosis and appropriate best practice ancillary testing, and linked to the detailed presentations in the WHO Thoracic ‘blue book’ [9]. The unique features of this reporting system are that it is applicable to all respiratory cytopathology specimens including exfoliative specimens, sputum, bronchial brushing and washing as well as FNAB, and that a differential diagnosis based on the cytopathological features is emphasised so that the WHO System can be used globally in all high-income countries (HICs) and low middle–income countries (LMICs) cytopathology services. Categories applied to pulmonary cytopathology assist communication between cytopathologists and their clinicians, but ultimately the aim of any cytopathology report is to provide as specific a diagnosis as possible.

The recommendations for the application of ancillary studies, include ICC and molecular studies for optimal patient care. There are also detailed guides in sampling methods and specimen preparation, the strategic use of rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) to increase the cost-effective and efficient triaging of specimens to optimise the handling of specimens, and discussion of the multidisciplinary approach [12].

While Benign and Malignant categories are the ‘traditional’ diagnostic categories with a definitive diagnosis and clear clinical approach in most instances, the Insufficient and particularly the indeterminate Atypical and Suspicious for malignancy categories reflect cases that present challenges in diagnosis and potentially further diagnostic management. The Atypical category includes cases that carry a low Suspicion for malignancy, but cannot be diagnosed as Benign. On the other hand, the Suspicious for malignancy category is intended for cases that have a high suspicion for malignancy, but qualitatively or quantitatively the material falls short for a definitive diagnosis of malignancy [14].

In this review, the specific focus will be on the Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic, Atypical and Suspicious for malignancy categories, which often contribute to complex challenges in patient management [11, 15, 16]. The diagnostic criteria for each category, along with associated challenges and future opportunities for addressing and better understanding these issues, will be discussed [9].

2 Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-Diagnostic Category

The success of any reporting system depends on it being practically applicable and reproducible and assisting the clinician in managing their patient. This requires a clear definition and associated recommendations for further workup for each category. From a very practical point of view, a fundamental starting point for each specimen is to establish as far as possible that the sample is representative of the targeted lesion. The proposed reporting system of the Japanese Society for Clinical Cytology (JSCC) reflects this by not even categorising lesions that are not adequate [8].

Specimen adequacy in lung cytopathology lacks universally accepted criteria, complicating the standardisation of diagnostic processes [17]. Despite the establishment of some criteria, such as requiring more than 10 alveolar macrophages per 2 mm2 for bronchial washes and BAL samples, or more than 40 lymphocytes per high power field in EBUS-FNAB of hilar lymph nodes [4], the reproducibility, sensitivity and specificity of these metrics remain low [17, 18]. This is largely attributed to the lung's complexity as an organ, characterised by diverse pathological entities, cell types and sampling techniques. These factors collectively impede the establishment of universally applicable criteria for specimen adequacy based on the number of any particular cell type present in a cytopathology sample. These challenges may have also contributed to the limited global acceptance of previous respiratory cytopathology reporting systems [17].

In the WHO System, specimens are categorised as ‘Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic’ when they do not contain adequate cellular material or exhibit technical issues that prevent a reliable diagnosis [9]. The samples in this category include inadequate cellular material, various preparation and obscuring artefacts such as poor smearing, staining, air-drying artefact in alcohol-fixed and Papanicolaou-stained smears, slow air-drying artefact in air-dried Giemsa-stained smears, or the presence of obscuring blood or mucus (Table 1). While the terms ‘Insufficient’, ‘Inadequate’ and ‘Non-diagnostic’ are often used interchangeably, it is required that each cytopathologist or institution consistently use one term [9].

|

No pathological infectious microorganisms, including bacteria, fungal elements, parasites, parasite ova, or larvae, in the intracellular or extracellular space No nuclear or cytoplasmic viral cytopathic effect No abundance of inflammatory cells (e.g., lymphocytes, neutrophils, or eosinophils) to suggest an inflammatory or allergic reaction No granulomatous inflammation No diagnostic matrix or acellular material such as fat, amyloid, clean mucin, proteinaceous fragments or foreign material Pulmonary macrophages that do not contain haemosiderin pigment, melanin pigment, fat vacuoles or other pathological substances suggestive of a pathological condition No cytopathological atypia of nuclei or cytoplasmic differentiation Sputum sample devoid of any pulmonary macrophages, or insufficient material to prepare two smears |

Designed to reflect global practices, the WHO System provides flexibility in categorising specimens with plentiful benign cells, such as bronchial epithelial cells and macrophages and other inflammatory cells as ‘Benign’, in an approach that gives primacy in the cytopathology report to actually reporting what is seen on the slides. The WHO System also emphasises the importance of correlating the cytopathological findings with clinical, imaging and microbiological findings in a ‘Triple test’ approach; therefore, when benign cells are accompanied by suspicious radiological images, it is mandatory in the diagnosis of such cases to add a caveat, stating that the material may not accurately represent the target lesion, and that further cytopathological assessment is required [9]. The WHO System recognises that practice varies, and an alternative approach to this situation categorising such a case as ‘Non-diagnostic’ is totally acceptable, with the same recommendation for the need for further cytopathological assessment. Above all else, clear communication with the clinical team as to which categorisation for these cases is being used by the cytopathologist is an absolute requirement. It is argued by some cytopathologists that categorising lesions with abundant benign material when there is an imaging target as ‘Benign’ may inevitably lead to higher ROM rates in both the ‘Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic’ and ‘Benign’ categories [9, 12].

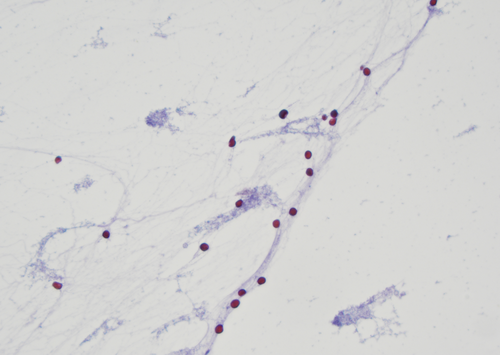

As detailed in Vuorisalo et al.'s study [19], which included a fishbone diagram analysing the causes of Insufficient, Inadequate and ‘Non-diagnostic’ samples, understanding the root causes for this categorisation is crucial for refining future editions of the WHO System. The study reviewed 248 EBUS-TBFNAB samples, categorising them into 46 insufficient samples, 60 with low cellularity and 142 adequate samples. The study highlighted that insufficient EBUS-TBFNAB samples can be due to human factors, diagnostic methods, sampling techniques and laboratory processing, and well-known issues including poor sampling technique (Figure 1) and suboptimal slide preparation are significant contributors to elevated Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic rates. To mitigate these challenges, the WHO System extensively details these factors in dedicated chapters on techniques of obtaining and handling exfoliative and FNAB specimens providing comprehensive guidelines aimed at enhancing the quality of cytopathological specimens [9].

3 Atypical Category

In lung cytopathology, the term ‘atypia’ has been used in a variety of ways over a long time [16] without any structured definition or recommendation until the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology for Respiratory Cytology definition [6, 17, 20]. In the WHO System, the Atypical category is defined as specimens with mainly benign features but which also exhibit some cytopathological features that are concerning as they may suggest a malignant neoplasm. The atypical specimen has insufficient features to make a definitive diagnosis due to qualitative or quantitative issues [9]. The acceptable rate of the Atypical category is approximately 3%–5% in different practice settings and variable types of cytopathology specimens and services [17]. The ROM is estimated to be 50%–60% [6, 17], although a better term is to regard this as the ‘rate of malignancy’ [21].

The ROM and recommendation for further diagnostic management is defined based on the method of specimen collection. The ROM for FNAB specimens is between 46% and 55% [22], while the ROM for sputum is 86%–100%, bronchial washing 62%–86% and bronchial brushing 79%–100% respectively [9, 17, 22, 23]. These are estimates based on the literature, which at this stage is based on varying patient cohorts and varying definitions of atypia, and further research is required to establish more precise ROM in both exfoliative and FNAB specimens.

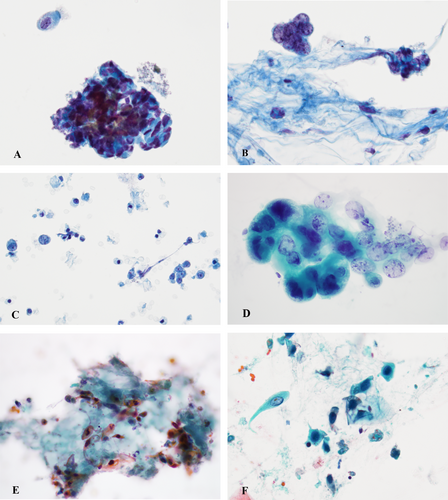

The contributing factors to an atypical specimen include the inherent characteristics of the target lesion such as nodule size, anatomical site and accessibility to sample, for example, central or peripheral, cellular component, the expertise of the operator, technical issues related to collecting the specimen, such as the patient's general health condition and proximity of the lesion to the vital organs, specimen preparation deficiencies such as the quality of the smearing, air-drying artefact of alcohol-fixed Papanicolaou stained slides and the pathologist's experience (Figure 2A–F) [17, 20].

In evaluating atypical cases, as with all respiratory specimens, it is required that the cytopathologist review clinical and imaging studies when the material on the slides is assessed as atypical [5, 17]. In imaging, the lesion's characteristics such as a solitary nodule versus multiple, well-defined mass versus ill-defined, and solid versus cavitating, assist the decision as to how to further work up the patient to reach as specific a diagnosis as possible [23]. Clinical history plays an important role, and may reveal a prior history of malignancy, previous or current infection, prior treatment for malignancy such as chemotherapy and radiation, and the status of the patient's immune system. Any current microbiological findings such as mycobacterial, viral or other infections also should be part of the assessment.

Atypical cells when present should be carefully evaluated for their cytomorphology. It is of paramount importance to distinguish if the atypical cells favour a neoplastic lesion vs. a reactive process [5, 14]. It is recommended that the cytopathologist in all atypical cases should provide a description of the cellular material detailing the atypical features and cell type such as epithelial, neuroendocrine features, inflammatory cell or rarely spindle cell. The Atypical category is not intended to be a waste basket of uncertain cases, and providing a description of the specific atypical features and a statement as to the possible aetiology is recommended. The cytomorphological features of the Atypical category are summarised in Table 2.

| Feature | Atypical category |

|---|---|

| Nuclear atypia | Mild to moderate nuclear enlargement and irregularities; low N:C ratio |

| Nucleoli | Small, occasional nucleoli |

| Chromatin | Mild hyperchromasia; occasionally coarse |

| Nuclear membrane | Slight irregularities |

| Cellular architecture | Minimal architectural distortion; no crowding |

| Presence of cilia | Often present (especially in reactive changes) |

| Associated conditions | Reactive changes, viral infections, treatment effects (chemotherapy/radiotherapy) |

| Interpretative guidance | Generally assessed with caution and context-dependent, considering clinical history |

| Recommended next steps | Further clinical, imaging correlation, possible follow-up FNAB |

Recommendations for the further workup of the patient and specific cytopathological procedures once a case is categorised as Atypical are related to the specimen type. For all respiratory specimens, correlation of the cytopathological findings with clinical, imaging and microbiological findings is required. Each FNAB case categorised as Atypical should be discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting. If the consensus favours a benign condition, then the patient can have routine follow-up in 3–6 months. However, if the overall conclusion is that there is uncertainty as to the diagnosis, then repeat FNAB, preferably with ROSE, is recommended with or without CNB [9]. Similarly, in cases of sputum specimens, bronchial washing and bronchial brushing, if the overall assessment is that of an infective or benign neoplastic process, then a watch-and-wait approach with clinical and/or imaging and/or microbiological follow-up can be recommended, and if the overall assessment remains uncertain, then FNAB with ROSE and/or CNB when appropriate is recommended [9].

Assessment of atypical epithelial cells or lymphoepithelial cells can be difficult due to low cellularity, and the same applies to spindle cells with bland cytomorphology, and in all cases limited material will preclude ancillary studies such as ICC, and lead to an increased incidence of Atypical categorisation [14]. It is not possible to strictly define universal criteria for atypia in pulmonary cytopathology, but the WHO System provides considerable discussion and illustration of the features of atypia in various specimen types. Reactive changes, inflammatory processes and infectious agents can present with cellular atypia such as post-chemotherapy and radiotherapy, metaplasia and hyperplasia, viral cytopathic effect and changes associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome [20].

Reactive and reparative changes may cause pronounced atypia characterised by nuclear atypia including nuclear enlargement, irregularities in the nuclear membrane and chromatin, and occasionally loss of cilia, although the N:C ratio generally remains low with cytomegaly and reactive bronchial cells nuclei remain oval with chromatin changes consistent within tissue fragments [14]. Metaplastic changes can be associated with atypia such as squamous metaplasia and goblet cell hyperplasia, concerning for squamous cell carcinoma and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, respectively [14].

Iatrogenic effect related to chemotherapy and radiotherapy may cause cellular atypia characterised by enlarged cells with pleomorphism, nucleomegaly and cytoplasmic vacuolisation while N:C remains unchanged or lowered [14].

Reserve cell hyperplasia can present as atypical cells characterised by tissue fragments of small cells with a high N:C ratio and round relatively uniform, hyperchromatic nuclei [14]. Table 3 summarises the non-neoplastic conditions manifesting as atypia.

| Non-neoplasctic atypia | Cytomorphological features |

|---|---|

| Inflammatory conditions | Disorganisation of the fragments with nuclear crowding and loss of architectural polarity |

| Viral infections |

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and other viral infections Enlarged cells with large round to oval nuclei, HSV with multinucleation, nuclear moulding and clearing of viral inclusions, CMV with owl-eye nuclei |

| Squamous metaplasia | Chronic infection or chronic irritation; round to oval squamous cells with high N:C ratio and hyperchromatic nuclei, occasionally associated with keratin debris, can mimic squamous cell carcinoma |

| Post-chemotherapy and post-radiotherapy changes | Cytomegaly with low N:C ratio, vacuolated cytoplasm and nucleomegaly with hyperchromatic nuclei |

| Reserve cell hyperplasia | Mostly encountered in bronchioalveolar lavage and bronchial brushing; small 3D fragments and sheets of cells with high N:C ratio, small cells with scant cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei, can mimic small cell carcinoma or neuroendocrine tumours |

| Type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia | Encountered in viral infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute respiratory distress syndrome; tissue fragments with variable degree of nuclear crowding and overlapping, enlarged nuclei with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli Abundant cytoplasm can mimic mucinous adenocarcinoma |

In general terms, a mild degree of increase in N:C ratio, anisonucleosis, nuclear membrane irregularities, unevenly distributed chromatin and nuclear crowding are cytomorphological features seen in the Atypical category [16, 20].

Background material in the absence of neoplastic cells may be categorised as Atypical, including necrosis, thick abundant mucin and keratinous debris [14].

Ancillary studies should be attempted to further characterise the atypical cells. If ROSE suggests atypical lymphoid cells, material can be sent for flow cytometry, while microbiology studies should be requested in cases that raise the possibility of infectious disease [24]. If ROSE cannot be performed, the cytopathologist should establish a set protocol for FNAB cases and for exfoliative specimens, where samples are provided that can be used for cell block, flow cytometry and microbiology in addition to cytopathology, and these should be discussed with and provided by clinical teams. A cell block and/or additional smears can be prepared for special stains for infections and ICC [24, 25]. Adequate material for ancillary studies may change the diagnostic category from Atypical to Benign, Malignant or Suspicious for malignancy. It is not recommended to perform ancillary studies on paucicellular specimens [24, 26].

4 Suspicious for Malignancy Category

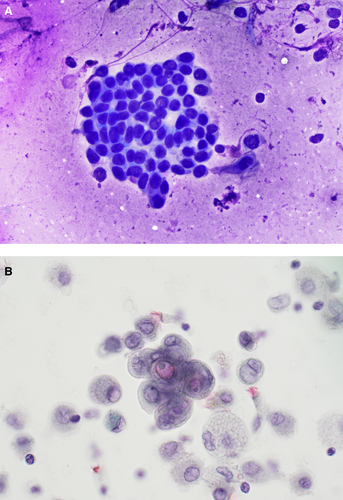

Suspicious for malignancy is a diagnostic category for cases expected to be most likely malignant, but the diagnostic features fall short in quantity or quality for a definitive and unequivocal diagnosis of malignancy (Figure 3A,B). This diagnostic category is applicable to all types of respiratory specimens, with an estimated ROM that is relatively high at 75%–88% for FNAB specimens, and an even higher ROM for exfoliative specimens of 100% for sputums, 83%–100% for bronchial washing and 75%–100% for bronchial bushings [9, 27]. As with the Atypical category, the Suspicious for malignancy category remains very subjective with a high inter-observer variability [28].

Factors contributing to this categorisation include the cytopathologist's experience, specimen type and cellularity, preparation methods, technical faults and the degree of architectural and cytopathological atypia. This diagnostic category is used to maintain the high PPV of the malignant category and to avoid a false positive diagnosis of malignancy and unnecessary intervention [6, 8, 13]. No discrete cytomorphological features are defined for this category, but marked nuclear atypia and/or architectural atypia are usually present including variability in cell size and shape, anisonucleosis, nuclear enlargement, irregular nuclear membranes, presence of prominent, large or spiculated nucleoli, and hyperchromatic or coarse chromatin and perinucleolar clearing, referred to in many cases as ‘vesicular’ nuclei [13, 14]. Architectural atypia includes loss of nuclear polarity, and nuclear crowding, overlapping and nuclear moulding in tissue fragments [14, 23].

Well-differentiated lung adenocarcinoma remains a diagnostic challenge due to the lack of classic malignant features in most instances and despite specimen adequacy. Therefore, most cases are categorised as Suspicious for malignancy. A very cellular FNAB specimen with extensive mild to moderate atypia nuclear in the presence of a mass lesion should trigger a differential diagnosis that includes well-differentiated adenocarcinoma [14].

When a specimen is categorized as Suspicious for malignancy, the pathology report should describe the specific cytopathological findings and cell type that are Suspicious for malignancy and state which malignancy is being considered likely and the differential diagnosis in challenging cases. For instance, ‘the cytopathological findings are suspicious for non-small cell carcinoma, although metastatic carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis’.

The Suspicious for malignancy category is linked to two main differential diagnoses: atypia resulting from reactive and reparative changes, and true malignancy [14]. But as with the Atypical category, there are no specific cytopathological findings to define the Suspicious for malignancy category. As detailed above in the atypical section, the WHO System discusses the cytopathological features for which a Suspicious for malignancy category is appropriate. Reactive changes can cause cytomegaly, nuclear enlargement, increase in N:C ratio, hyperchromatic nuclei, and occasionally nucleoli and irregularity in nuclear membrane. Viral cytopathic effects like those seen in cytomegalovirus infection, reactive changes after lower respiratory tract infection and treatment effects after chemotherapy and radiotherapy can cause atypia that is highly Suspicious for malignancy, and assessment of residual and recurrent lung carcinoma after treatment remains a challenging area. The presence of cilia on bronchial cells is a useful diagnostic clue for reactive changes.

As discussed in the Atypical category, squamous metaplasia can show reactive changes varying from mild to marked atypia, leading to false diagnoses of squamous cell carcinoma [13], and atypia of squamous cells should be evaluated in the context of imaging and clinical history.

Overall, studies support that ROSE reduces the rate of the Suspicious for malignancy category [26]. However, factors like small tumour size, extensive necrosis, fibrosis and prior treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy may contribute to the low cellularity of the specimens [14]. Ancillary studies including ICC on cell blocks or cytopathology slides can be helpful to reach a definitive diagnosis of malignancy in a subset of cases initially assessed as Suspicious for malignancy in up to 5% of cases in one study [9, 17].

The recommended diagnostic management for the Suspicious for malignancy category to further workup a patient, as with the Insufficient/Inadequate/Non-diagnostic and Atypical categories, is to correlate cytopathological findings with clinical, imaging and microbiological findings and then to discuss the case in a multidisciplinary meeting. If all findings favour a malignant process, then in most cases, repeat FNAB ideally with ROSE and triaging for ancillary tests and CNB where available will be recommended. However, the patient in some circumstances may be treated for malignancy. However, if the cytopathology findings do not correlate with clinical, imaging and microbiology findings, then repeat FNAB with ROSE with or without CNB is recommended before any definitive treatment [9]. The cytomorphologic features of Atypical and Suspicious for malignancy categories are summarised in Table 4.

| Feature | Suspicious for malignancy category |

|---|---|

| Nuclear atypia | Marked nuclear atypia, variability in cell size and shape, and high N:C ratio |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, large or spiculated nucleoli |

| Chromatin | Hyperchromatic, coarse, with perinucleolar clearing or ‘vesicular’ nuclei |

| Nuclear membrane | Irregular, often with folding or notching |

| Cellular architecture | Loss of polarity, nuclear crowding, overlapping and nuclear moulding |

| Presence of cilia | Usually, absent |

| Associated conditions | High likelihood of malignancy, requiring further evaluation |

| Interpretative guidance | High Suspicion for malignancy but lacking enough criteria for definitive diagnosis of malignancy |

| Recommended next steps | Repeat FNAB with ROSE, ancillary testing (ICC), potential CNB if available |

5 Conclusion

The WHO System is an international effort to standardise category definitions, establish the key diagnostic cytopathological features of entities of the lung, propose the best use of ancillary tests in lung specimens, encourage the use of standardised pathology reports containing essential components in an integrated report, and propose estimates of the risk stratification for each diagnostic category based on the current literature, and recommend further diagnostic management. The ultimate aim is to improve patient care globally regardless of the available local medical resources by creating a common language between cytopathologists and clinicians, but the Inadequate/Insufficient/Non-diagnostic, Atypical and Suspicious for malignancy categories can often lead to miscommunication or frustration while the diagnosis still remains very subjective. There has to be clear discussion between the pathologist and clinician because these categories frequently require additional cytopathological evaluation, CNB, appropriate ancillary tests and discussion in tumour boards whenever available to establish a specific diagnosis. The clinician's expertise in obtaining exfoliative or FNAB specimens, the skill of the cytopathologist and the collaboration between these specialists are crucial for accurate and effective pulmonary cytopathology practice. Factors such as the site and size of the target lesion, its characteristics that may include solid, cystic or necrotic components, the availability of ROSE, efficient and cost-effective specimen triaging, specimen preparation techniques and access to ancillary tests, including CNB, all play a role in determining the rates of these three diagnostic categories. In addition to these technical aspects, open and detailed communication between cytopathologists and clinicians has long been emphasised in practice. The WHO System aims to establish a new framework—a common language—to better address these well-known challenges in patient management.

This review serves as an explanatory guide for applying these three strategic categories in patient management, building on established practices and enhancing clarity in diagnostic communication.

Author Contributions

All three authors contributed to the concept of the article, its writing and editing.

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to report. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Notre Dame Australia, as part of the Wiley - The University of Notre Dame Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.