Fine Needle Aspiration of CD20-Negative Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma Presenting as an Anterior Neck Mass

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Abstract

Aggressive lymphoma of the neck presenting with life-threatening airway compromise requires quick diagnosis, which can be rendered with fine needle aspiration cytology. In atypical cases, using multiple B cell markers can be helpful to avoid misdiagnosis.

1 Introduction

High-grade lymphoma of the neck can swiftly cause airway compromise, and therefore prompt diagnoses are vital. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) can quickly differentiate lymphoma from other malignancies and can often subtype it [1]. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is aggressive but can respond well to chemoimmunotherapy [2]. Its diagnosis requires evidence of B cell lineage, usually assessed by CD20 immunohistochemistry [2]. Here, we present a case of an anterior neck mass clinically suspicious for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma but ultimately diagnosed as CD20-negative DLBCL. This case highlights the utility of FNAC in rapid diagnostic workup and emphasises the importance of using multiple B cell markers to assess lymphocyte lineage.

2 Case History

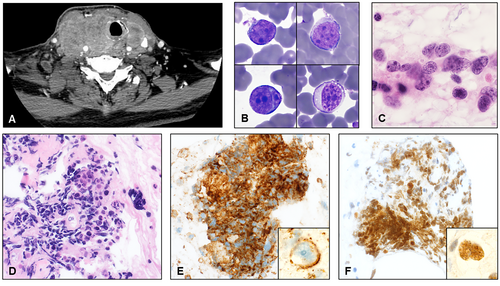

A 74-year-old man with a 30-pack-year smoking history presented to otolaryngology clinic with a neck mass with several weeks of brisk growth, dyspnoea, and dysphagia. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 10.2-cm anterior neck mass (Figure 1A), possibly arising from the thyroid, with extensive neck lymphadenopathy and multiple pulmonary nodules. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (7.534 microunits/mL) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, 687 units/L) were increased. Free thyroxine (0.69 ng/dL) and haemoglobin (12.4 g/dL) were decreased. Leukocytes numbered 8300/μL. Laryngoscopy demonstrated significant supraglottic oedema shifting the laryngeal structures and a narrowly patent airway.

3 Materials and Methods

Superficial aspiration was performed using a 25-gauge needle and 10-mL syringe by palpation. Rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) was performed using ethanol-fixed slides stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and air-dried, Diff Quik-stained slides. The cell block was made from 19 mL of bloody RPMI with particles and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

4 Results

Fine needle aspiration cytology was hypocellular and showed rare scattered, discohesive and partially crushed small- to medium-sized round cells with scant cytoplasm, large, hyperchromatic nuclei with smooth borders, vesicular chromatin, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B,C) in a background of blood elements and minimal follicular cells. Colloid, mitoses and necrosis were not identified. At the time of the procedure, a cytotechnologist performed a rapid on-site evaluation, which was deemed ‘adequate’. The case was reviewed soon after by the pathologist, and the diagnosis of ‘malignant cells present’ was rendered. Flow cytometry (FC) was not requested, and all residual material was sent for cell block (Figure 1D). The patient underwent emergency surgery to secure his airway and expedite workup of a suspected anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC). Meanwhile, cell block immunohistochemistry was positive in the lesional cells for CD45 and PAX8 (Figure 1E,F, respectively) and negative for calcitonin, TTF-1, thyroglobulin and pan-cytokeratin.

Open biopsy (Figure 2A) performed during surgery demonstrated fibrous tissue and skeletal muscle involved by a diffuse infiltrate of large-sized cells with irregular nuclei, vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli and moderate amounts of cytoplasm with large areas of necrosis. The lesional cells were notably negative for CD20 (Figure 2B) and CD79a but were strongly and diffusely positive for other B cell markers, including PAX5 (Figure 2C) and CD19, and for CD30 (Figure 2D) and MUM1. EBER in situ hybridisation was negative. PAX8 was again positive in lesional cells. FISH was negative for MYC, IGH::BCL2 and BCL6 rearrangements. This case was a nongerminal centre subtype per the Hans classification, featured a high Ki67 proliferation rate (> 90%), and showed a double-expressor phenotype, with diffuse positivity for MYC and BCL2 by immunohistochemistry. FC was not performed on the cytology specimen nor the open biopsy.

Unfortunately, the patient's disease was refractory to rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone chemotherapy, anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy (CAR-T) and several additional chemoimmunotherapy regimens. He ultimately passed away 1.5 years after presentation.

5 Discussion

Fine needle aspiration cytology can quickly provide actionable diagnostic information to guide patient management. This is particularly important when encountering rapidly growing neck masses compressing the airway. In this case, H&E and Diff Quik-stained smears were moderately cellular and demonstrated several clusters of atypical large cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios in a background of mostly blood. Colloid and necrosis were not present. The differential diagnosis was broad and included ATC, medullary thyroid carcinoma, high-grade lymphoma, high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, sarcoma, melanoma, germ cell tumour and metastatic carcinoma. On FNAC, lymphomas are almost always discohesive with scant cytoplasm, range from monotonous to pleomorphic, can have crush artefact on smearing and can feature stripped nuclei and lymphoglandular bodies. ATC is typically highly cellular with pleomorphic nuclei, moderate cytoplasm and necrotic debris. Tumour cells with more differentiation and squamous metaplasia can be clues to ATC. Medullary thyroid carcinoma can show variable cellularity and morphology, including plasmacytoid, pleomorphic and spindled forms. The lesional cells of this case were positive for PAX8 and CD45 and negative for calcitonin, TTF-1, thyroglobulin and pan-cytokeratin. ATC is frequently negative for TTF-1 and thyroglobulin but will stain for PAX8 and cytokeratin. Importantly, antibodies targeting the N-terminus of PAX8 can cross-react with the B cell transcription factor PAX5, due to sequence homology between the N-terminal domains of PAX8 and PAX5 [3]. Therefore, PAX8 positivity should be interpreted in the context of additional markers, including CD45, other B cell markers (i.e., CD20, CD79a, and CD19), and cytokeratins.

Differentiating lymphoma from nonhaematolymphoid malignancies is crucial as lymphoma is typically not treated with surgical resection. FNAC combined with FC can diagnose lymphoma with accuracy up to 99.3% [1, 4, 5]. Large-cell lymphoma yields the highest false-negative rate, due to poor aspiration and loss of cells during FC [1, 6]. Additional tissue sampling can be helpful. In a retrospective study of 65 patients with thyroid lymphoma who underwent FNAC as their first diagnostic test, core biopsy had a higher sensitivity than FNAC (93% vs. 71%, p = 0.006) and a lower false-negative rate (7% vs. 29.2%, p = 0.048) [7]. In this case, an open biopsy, prompted by the cytopathologic impression, allowed for definitive diagnosis, including exclusion of mediastinal grey zone lymphoma (MGZL), the leading haematopathologic differential diagnosis.

A diagnostic consideration was primary thyroidal lymphoma, such as DLBCL (PT-DLBCL) or marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (PT-MALT lymphoma). PT-DLBCL comprises approximately 0.5%–3.5% of thyroid malignancies and over half of thyroid lymphomas [8] and is most common in older female patients [8]. In a study of 58 patients with PT-DLBCL, the average size of the presenting neck mass was 3.8 cm, 41% had elevated LDH at presentation, and 38% had a history of lymphocytic thyroiditis [9]. Approximately 50% showed neck or mediastinal lymph node involvement [9]. PT-MALT is the second most common thyroid lymphoma comprising around 10% of cases [8, 10]. In contrast to PT-DLBCL, it has an indolent course [10]. Cytologically, PT-MALT is composed of mildly atypical, monomorphic lymphocytes, and distinguishing it from reactive lymphocytes is challenging without immunostudies [11]. It has a very strong association with Hashimoto thyroiditis, with some reports citing up to 72% of PT-MALT showing evidence or history of Hashimoto thyroiditis [10]. Notably, this patient had no history of lymphocytic thyroiditis. Given the absence of thyroid parenchyma on FNA and excisional biopsy and the equivocal imaging findings, we ultimately could not definitively determine whether this represented a primary thyroid lymphoma with extrathyroidal extension or a nodal lymphoma that spread into the central neck anatomy.

Positivity for CD20 is typically a reliable feature that can help identify B cell lymphomas of the thyroid region on FNAC [11, 12]. In Huang et al.'s study of thyroid DLBCL and MALT diagnosed on FNAC, CD20 IHC was positive in all 19 cases [11]. The lack of CD20 and CD79a expressions in this case was unusual. This, along with the strong, diffuse CD30 expression and the diffuse growth pattern, raised the possibility of MGZL. However, there was no mediastinal mass, and the lesional cells were strongly positive for CD45, PAX5 and CD19 and negative for CD15, making the overall morphology and immunophenotype best classified as DLBCL. This highlights the utility of using multiple haematolymphoid markers when evaluating FNAC for B cell lymphoma. Additionally, CD20 negativity suggested that the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab would have limited therapeutic effect. However, diffuse CD30 positivity provided an additional therapeutic target, and the patient received the anti-CD30 antibody–drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin for disease relapse following CAR-T therapy.

In summary, we present a CD20-negative DLBCL presenting as a large anterior neck mass. In cases of rapidly enlarging neck masses, particularly in emergent situations, FNAC can promptly distinguish lymphoma from other entities on the clinical differential, such as carcinoma or sarcoma, allowing for appropriate treatment. FC is a useful ancillary study when lymphoma is in the differential diagnosis. Finally, employing multiple B cell markers, through either FC or immunohistochemistry, can be helpful in resolving atypical cases and avoiding misdiagnosis.

Author Contributions

Connor Hartzell: manuscript writing, reviewing, editing, figures. Emily F. Mason: reviewing, editing, figures. Christopher O'Conor: conceptualization, reviewing, editing.

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to report.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data used to construct this manuscript can be made available upon reasonable request.