Fine needle aspiration cytopathology of pleomorphic dermal sarcoma

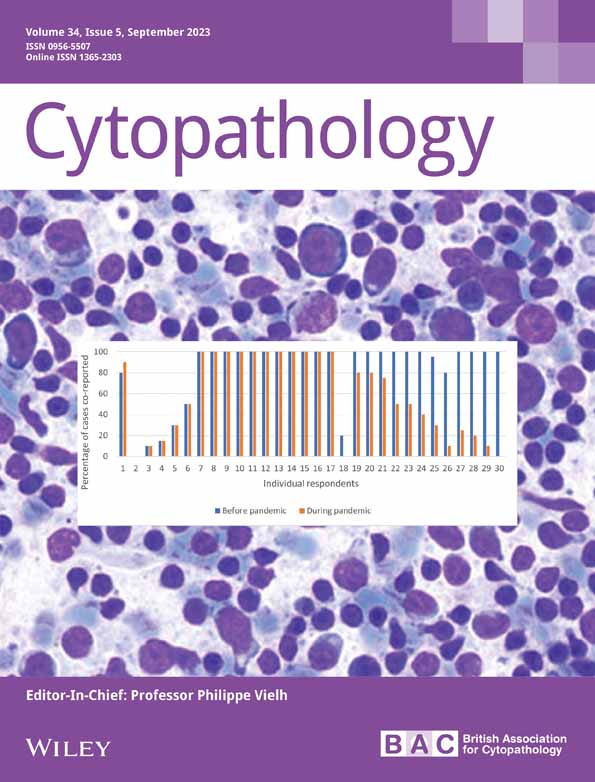

Abstract

Introduction

Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS) is an uncommon cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm. It is cytomorphologically identical to atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), but differs due to its invasion beyond the dermis. We undertook an examination of our experience with fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy cytology of PDS.

Materials and Methods

Our cytopathology files were searched for examples of PDS with concomitant histopathological verification. FNA biopsy smears and cell collection were performed using standard techniques.

Results

Seven cases of PDS were retrieved from four different patients (M:F, 1:1; age range: 63–88 years; mean age = 78 years). All patients (57%) presented with a primary tumour with one having an FNA biopsy of two local recurrences and a single distant metastasis. Five aspirates were from the extremities and two from the head/neck. Tumours ranged from 1.0 to 3.5 cm (mean, 2.2 cm). Specific cytological diagnoses were pleomorphic spindle/epithelioid sarcoma (3 cases), PDS (2), AFX (1), and atypical myofibroblastic lesion, query nodular fasciitis (1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining from FNA-generated cell blocks in two cases showed non-specific staining with vimentin in both cases; positive CD10, CD68, and INI-1 staining in one case; and smooth muscle actin expression in the other. Multiple negative stains were performed in both of these cases to exclude malignant melanoma, carcinoma, and specific forms of sarcoma. Cytopathology consisted of a mixture of spindle, epithelioid, and bizarre pleomorphic cells.

Conclusion

Coupled with ancillary IHC stains, FNA biopsy can help recognise PDS as a sarcomatous cutaneous neoplasm, but is unable to distinguish PDS from AFX.

Graphical Abstract

Reports of the fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytopathology of pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS) are rare with this being the only series on the subject to date. FNA biopsy smears consist of a mixture of large spindle, epithelioid, and bizarre pleomorphic cells. Distinguishing PDS from atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is not possible using FNA biopsy.

1 INTRODUCTION

Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS), occasionally designated in years past as undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) or malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), is currently defined in the most recent WHO classification of skin tumours as a malignant cutaneous neoplasm that is genetically, morphologically, and clinically related to atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX).1 Unlike AFX, however, the term PDS was proposed by Dr CDM Fletcher to describe an AFX-like dermal neoplasm not merely confined to the dermis, but demonstrating invasion into subcutaneous fat, skeletal muscle, or beyond and frequently displaying features not seen in AFX such as necrosis, perineural invasion, or vascular space invasion.2-4 To our knowledge, fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy cytopathology of PDS is the subject of a single case report.5 Nonetheless, it is possible that there may be prior cytological studies where the terms UPS or MFH were used for cutaneous neoplasms that we were unable to extract from the literature as being true cases of PDS. In this communication, we present the cytopathology, diagnostic challenges, and differential diagnostic possibilities encountered from a series of seven FNA biopsy cases of PDS.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

A review was made of our cytology and surgical pathology databases for cases interpreted as dermal sarcoma, and as AFX. Non-cutaneous soft tissue tumours were excluded from this study. Patient demographics, clinical presentation, and cytopathological diagnoses were recorded. A requirement for study inclusion was that all cytology cases have a confirmatory histopathological diagnosis of PDS.

Percutaneous palpation-guided FNA biopsy was performed on cutaneous nodules using standard technique with a 21-gauge needle without image guidance. Three to four passes were made into the mass, and each needle pass rinsed into RPMI-1640 balanced salt solution after expelling material onto glass slides to create conventional smears. No liquid-based slides were made. All smears were air-dried. Immediate microscopic assessment was made on half the smears after staining with a Romanowsky-based stain (R-stain). Subsequent Papanicolaou staining was performed on the remaining half after rehydration and alcohol fixation. Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded cell blocks (CBs) were made in all cases using the plasma thrombin technique from cells captured in the RPMI needle-rinsed solution. These were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. A panel of immunohistochemical (IHC) markers was performed if cellular material was present in the CB. IHC staining was performed using standard heat-induced epitope retrieval methodology and commercially available antibodies. No corresponding core needle or incisional biopsy was obtained at the time of FNA for any case.

3 RESULTS

Seven FNA biopsy smears and CBs of PDS were retrieved from four different patients (M:F = 1:1). No cytological cases of AFX were found or could be retrieved in our search. All patients presented with a primary neoplasm, and a single patient had FNA biopsies of her primary tumour as well as two subsequent local recurrences and a single distant metastasis over a 7 year time span. Patient ages ranged from 63 to 88 years (mean, 78 years). Tumours ranged from 1.0 to 3.5 cm (mean, 2.2 cm; Table 1). Specific cytological diagnoses were pleomorphic spindle/epithelioid sarcoma (3 cases), PDS (2), atypical fibroblastic proliferation suspicious for recurrent AFX (1), and atypical myofibroblastic lesion, query nodular fasciitis (1). One aspirate specifically interpreted as PDS was from a local recurrence, and the other with a PDS diagnosis was from a metastatic deposit. Three patients had a history of other tumours. Two had prior non-melanocytic, UV radiation-associated head and neck skin tumours (basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma). One of these patients also had a history of prostate cancer. The third patient had a history of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. All patients remain alive (follow-up 2-104 months, mean: 42.5 months).

| Case # | Age (years)/sex | Site | Presenting symptoms | Imaging findings | Cytological diagnosis | Tissue diagnosis | P/Re/M | Tumour size (cm) | Cell block ancillary testing | Other tumours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.a | 82/F | Left forearm | Minimally tender 4 cm soft tissue mass in left forearm | MRI: Homogenous, lobulated subcutaneous mass over posterior ulna | Atypical myofibroblastic lesion, query NF | PDS | P | 2.0 | No cells |

BCC of nose, multiple skin lesions (diagnosis unknown) removed 20 years earlier |

| 2.a | 83/F | Left forearm/elbow | Painful mass at previous surgical site in left forearm | MRI: Enhancing, lobulated nodule in surgical bed overlying dorsal cortex of proximal ulna |

Atypical fibroblast proliferation suspicious for recurrent AFX |

PDS | Re | 1.8 | No cells | See case 1 |

| 3.a | 85/F | Left forearm/elbow | Painless, firm, fixed mass over left ulna | MRI: Increased prominence of mesenteric enhancement around proximal ulna | PDS | PDS | Re | 1.5 | No cells | See case 1 |

| 4.a | 88/F | Left knee | Painless superficial soft tissue mass on left knee | MRI: Avidly enhancing ovoid mass in anterior subcutaneous tissue abutting vastus medialis | PDS | PDS | M | 2.0 | No cells | See case 1 |

| 5. | 69/M | Right ear | Enlarging, erythematous, exophytic, fungating lesion over right auricle | CT: Expansile 3.1 cm soft tissue mass involving posterior helix | Pleomorphic spindle/epithelioid neoplasm | PDS | P | 2.5 | + SMA, vimentin; neg. p40, CD31, CK AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, S-100, Melan-A, HMB-45, SOX-10, h-caldesmon | p16/HPV positive SCC of oropharynx |

| 6. | 63/M | Face | Slowly enlarging nodule on left cheek overlying the parotid gland | CT: Well-defined hypodense lesion in superior lobe of parotid | Pleomorphic sarcoma | PDS | P | Unknown | No cells | SCC of scalp, multiple non-melanoma skin cancers, prostate cancer |

| 7. | 75/F | Anterior tibia | Firm, mobile, subcutaneous mass over proximal tibia | MRI: Solid, avidly enhancing lobulated mass in subcutaneous fat along with anterior aspect of proximal tibia | Sarcoma with epithelioid features | PDS | P | 3.5 | + CD 68, vimentin, CD10, INI-1, TFE3 (nuclear); neg. Melan-A, HMB-45, SOX-10, ERG, CD34, CK AE1/AE3, claudin-4, EMA, desmin SMA, CAM 5.2, PAX-8, STAT-6, SS18. Negative RNA sequencing. | None |

- Abbreviations: AFX, atypical fibroxanthoma; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CK, cytokeratin; CT, computed tomography; M, metastatic; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NF, nodular fasciitis; P, primary; PDS, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma; Re, recurrent; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

- a Same patient.

3.1 Cytopathology

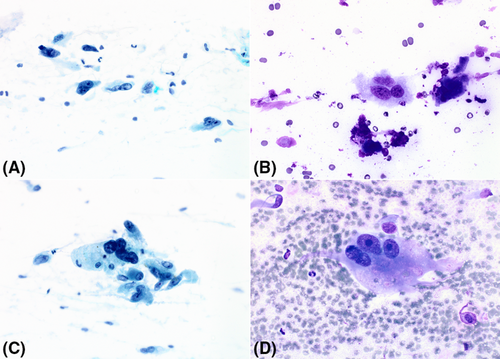

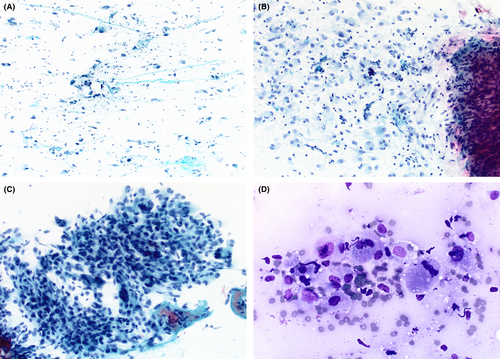

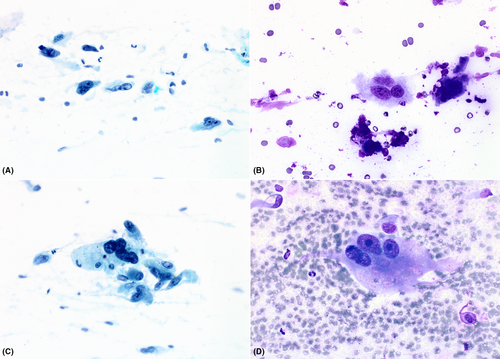

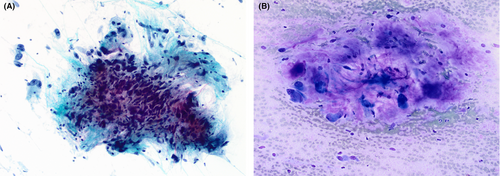

Smears varied from being only moderately cellular to markedly hypercellular, and composed of spindle and polygonal cells dispersed singly, and in both loose and tightly-aggregated clusters. Dense hypercellular three-dimensional groups were common. Spindle cells varied from being thin to larger forms exhibiting nucleomegaly, coarse to finely granular chromatin, variable-sized nucleoli, and having both short and long tapering cytoplasmic processes. Polygonal/epithelioid cells had variable amounts of finely granular cytoplasm with eccentrically positioned euchromatic as well as hyperchromatic nuclei. Infrequently, cytoplasmic microvacuoles were best seen in R-stained smears (Figure 1). Very large mono- and multinucleated pleomorphic cells were the third principal cell type encountered. These were randomly scattered within or adjacent to spindle/epithelioid cell clusters, and also commonly dispersed as single cells. They demonstrated marked hyperchromasia, irregularly contoured nuclei, and occasional macronucleoli (Figure 2). In some smears, tufts of collagenous stroma with a fibrillar edge were seen, while in other areas the stroma appeared as thin stringy wisps of collagen. In some smears, the stroma was more myxoid to fibromyxoid (Figure 3). Mitotic figures were present but uncommon, and somewhat surprisingly, background necrosis was largely absent.

Due to the lack of cells in accompanying CBs, IHC staining was performed in only two cases. These two that had adequate material for ancillary testing were the largest tumours (3.5 and 2.5 cm) in our series which could explain their higher yield compared to others. We are uncertain as to the reasons for the lack of diagnostic cells in the other five CBs. However, tumour size, the deep-seated nature of the lesion, and the decision of the cytopathologist to prioritise obtaining a higher smear yield over CB yield could have played a role in causing these results. IHC showed non-specific staining with vimentin in both; positive CD10, CD68, and INI-1 stain retention in one; and smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining in the other. Most of the negative stains listed in Table 1 in these two cases were performed to exclude other pleomorphic malignancies such as malignant melanoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and specific forms of sarcoma such as angiosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and synovial sarcoma. RNA sequencing in one case showed no specific pathogenic mutations.

4 DISCUSSION

PDS is an undifferentiated cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm with a definite risk for local recurrence, and for distant metastases.6, 7 As a condition of its uncertain histogenesis, it fails to immunohistochemically express epithelial, melanocytic, vascular, or myogenic markers. Given its propensity to arise in chronic ultraviolet (UV)-exposed skin, most examples have been reported in the head and neck region, particularly the scalp of elderly men.6, 8 PDS shares with AFX similar UV signature mutations in TP53, TERT promoter mutations, and frequent mutation in NOTCH1/2 and FAT1. Both have similar DNA methylation profiles and DNA copy number aberrations also.9-11 Two of our four patients had a history of prior cutaneous UV-associated skin malignancies, and two had head/neck tumours, while the other two cases were extremity-based neoplasms. Because of the histomorphological and genetic similarities to AFX, PDS is believed to represent one end of a common tumour spectrum.10, 12, 13 Four cases in our series had a tumour size of ≥2.0 cm consistent with findings in previous studies that showed PDS inclined to be ≥2.0 cm, while AFX usually tends to measure <2.0 cm.3, 14, 15 Of the two cases having tumours <2.0 cm in our series, both were recurrent tumours from the same patient. Their detection at this smaller size was likely due to close clinical follow-up following this patient's initial PDS diagnosis.

Cytomorphological findings from our series mirrors the histopathological intra-tumoral heterogeneity seen in histopathological descriptions of tissue specimens of PDS.3 We describe an admixture of large spindled cells, epithelioid cells, as well as multinucleated tumour giant cells having bizarre pleomorphic and anaplastic nuclei in smears from seven cases of PDS as seen in tissue specimens. However, additional features of PDS (that are absent in AFX) that cannot be appreciated in FNA cytopathology include invasion of subdermal structures such as subcutaneous fat, muscle, and underlying fibrous tissues including fascia, and the presence of perineural or venous invasion.16-18

Since most cutaneous nodules in adults are sampled using punch, shave, or excisional biopsy, it is not completely surprising that FNA reports of AFX and PDS are seldom encountered in most cytopathology laboratories. Ours represents the first FNA biopsy case series of PDS. The only prior report we uncovered regarding PDS cytology was that of a metastatic deposit to a regional lymph node by Smith et al.5 Those authors report cytological findings similar to those encountered in our seven aspirates. Five cases (71%) were correctly recognised as being malignant in this series. Two of our aspirates, one a local recurrence and one a metastasis from the same patient, were specifically interpreted as PDS cytologically. An additional two cases were correctly recognised as sarcomas with remaining cytological diagnoses being atypical fibroblastic proliferation suspicious for recurrent AFX, atypical myofibroblastic lesion query nodular fasciitis, and pleomorphic spindle/epithelioid neoplasm. Case #2 was interpreted cytologically as suspicious for recurrent AFX because this patient's original histopathological diagnosis was an incorrect diagnosis as AFX. Retrospectively, that tissue specimen was correctly recognised as PDS, not AFX, after her second surgical resection, and comparison of both tissue specimens. No case was interpreted as benign.

The major entity in the differential diagnosis of PDS is, of course AFX. Although FNA biopsy reports of AFX are completely lacking from our literature search, based on the fact that both tumours share the same cellular population, it is difficult to imagine one would be able to distinguish PDS from AFX based merely on cytomorphological features in smears, as invasive tumour depth is an inaccessible feature using FNA. Also, this distinction would still not be possible if a CB was acquired with the FNA biopsy—even if coupled with immunohistochemical data, since both tumours share the same immunohistochemical profile with expression of CD10, CD68, and SMA which unfortunately are relatively non-specific. Some features on aspirate smears such as necrosis and easily found mitoses could suggest the possibility of PDS over that of AFX. However, FNA biopsy smears lack the spatial advantages offered with a histopathological specimen whereby subcutaneous tissue invasion, muscle invasion, perineural invasion, and lymphovascular space invasion can be readily seen. Conversely, imaging may potentially help in this distinction. In our series CT or MRI from 6 of 7 cases showed a deep-seated subcutaneous lesion extending to or abutting the underlying bone.

Other diagnostic entities to be considered in an aspirate of PDS include a variety of primary pleomorphic cell cutaneous neoplasms and cutaneous metastases. As PDS is a diagnosis of exclusion due to a lack of tumour-specific markers,15 sufficiently cellular FNA-procured CBs are required to create a logical, but extensive IHC panel to exclude entities such as cutaneous poorly-differentiated angiosarcoma (ERG, CD31, CD34, MYC expression), sarcomatoid/spindle cell squamous carcinoma (expression of multiple pan-cytokeratin markers such as MNF116, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, cytokeratin 5/6, p63, and p40), leiomyosarcoma (SMA plus desmin positivity), and spindle cell and de-differentiated malignant melanoma (S100, SOX10, Melan-A, and HMB45 staining). Unfortunately, only two of our cases had sufficient cellular material to perform ancillary testing. In future cases, dedicating an entire aspirate directly for a CB should help increase cell yield thereby permitting a comprehensive IHC panel to be performed.

In summary, although the latest iteration of the WHO classification of skin tumours states that FNA cytopathology of PDS is clinically “not relevant,”1 we have demonstrated to the contrary that FNA is able to specifically recognise PDS in recurrent and metastatic cases, and is also able to suggest the possibility of that diagnosis in patients presenting with primary tumours. A larger series of PDS cases would assist in further clarifying the role of FNA cytopathology for this neoplasm. Although we had no FNA examples of AFX per se to compare with our PDS cases, nor any to compare with prior cytological descriptions of AFX from the literature, we believe that distinguishing PDS from AFX is not possible using this biopsy technique because of their widely documented clinical, morphological, immunohistochemical, and genotypic similarities.

5 AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Paul E. Wakely, Jr.: Study conception and design, collation of cases, formal analysis, project administration, validation, visualization, editing. Bindu Challa: Data curation, literature review, visualization, writing - original draft, resources, writing - review and editing. Jose A. Plaza: Review and editing, validation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare there is nothing to disclose.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.