Smoking Cessation Practices in Australian Oncology Settings: A Cross-Sectional Study of Who, How, and When

Study presented: Sydney Cancer Conference 2022.

Funding: This project is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1169324); Cancer Council Australia; Cancer Council Victoria, Quit Victoria.

ABSTRACT

Purpose

Patients who smoke tobacco during and after a cancer diagnosis have poorer health outcomes. Oncology healthcare providers (HCPs) are crucial to providing smoking cessation support. The study examined the characteristics associated with differences in HCPs’ smoking cessation practices.

Methods

As part of the Care to Quit trial, a cross-sectional survey exploring smoking cessation practices was completed by HCPs across nine cancer centers in New South Wales and Victoria, Australia.

Results

One hundred and seventy-seven HCPs completed the survey. Over half of the HCP respondents reported asking patients their smoking status, but fewer than half advised patients about the benefits of quitting, referred patients to behavioral support such as Quitline, or offered pharmacotherapy medication. All components of the “3A's” model (Ask, Advise, Act) were more likely to be completed by doctors compared to registered nurses (OR: 7.86, 95% CI: 3.64, 16.95, p<0.001), by those with more years of practice (OR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.07−0.93, p = 0.039), and those who had received smoking cessation training (OR: 3.91, 95% CI: 1.80, 8.48, p = 0.001). Multivariate analyses also identified differences in the amount of cancer-specific advice provided between occupation type (p<0.001) and years of practice (p = 0.021).

Conclusion

The need for smoking cessation care training in oncology continues to be apparent. Training in prescribing pharmacotherapies (for doctors) or supporting the use of pharmacotherapies (for nurses) is a particular “gap.” Differences between the roles and engagement of doctors and nurses in relation to smoking cessation care should be carefully considered when developing site-specific models of cessation care and providing training.

1 Introduction

There is substantial evidence that smoking tobacco after a cancer diagnosis is causally linked to adverse health outcomes [1]. Cessation after diagnosis can improve treatment outcomes and decrease the chance of secondary cancers [2-10].

Globally, government and nongovernment bodies are providing governance and guidelines to address smoking cessation care within oncology [11-15] and have emphasized the importance of a brief smoking cessation intervention in oncology clinics. A brief intervention [12] is regarded as all oncology healthcare providers (HCPs) asking patients about their smoking status, advising patients of the benefit of quitting, and acting by providing referrals to cessation services (3A's model). Acting includes referral to the free national telephone cessation support service (Quitline; icanQuit.com.au) and providing pharmacotherapy (e.g., nicotine replacement therapy [NRT] or varenicline). Despite these guidelines, best-practice delivery of cessation support is suboptimal. Globally across repeated large-scale survey data of Oncology and physicians, asking and advising patients occurs often (>90%), but active referral is less common, with reports of less than 40% providing medication options and very few providing follow-up support [16-18].

Increased efforts are evident by government bodies to mitigate the risk of tobacco smoking after a cancer diagnosis. One example is the NSW Cancer Institute (CINSW) training and development of an automated option for referral to Quitline. Efforts to embed cessation practices are emerging with a smoking cessation checklist implemented within three NSW oncology services during 2019–2020, showing an increase in oncologist and nurse screening of current smokers (up to 92% uptake), with increased confidence to advise and refer patients to appropriate services, and one in four patients progressing with a referral [19]. However, the apparent momentum toward increased smoking cessation care in oncology was anecdotally reported to be affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated pressures on staffing and resources. There is also a lack of data regarding whether the whole oncology team is engaged in providing smoking cessation support, and how smoking cessation is framed in terms of the cancer-specific benefits of cessation.

-

To report on the smoking cessation practices of a sample of oncology HCPs (including doctors, nurses, and allied health) in nine oncology services.

-

To examine the demographic characteristics associated with differences in smoking cessation practices among oncology HCPs.

-

To describe provider views regarding training and the timing of smoking cessation support.

-

To examine the type of cancer-specific advice given by oncology HCPs and the demographic factors associated with benefit provision.

2 Methods

2.1 Recruitment

During initial trial meetings with the relevant departments, HCPs were provided with information sheets about the trial and asked to complete a baseline survey either electronically or in paper form [20]. Reminder emails were sent 1–2 weeks prior to the survey closing. Participation in the survey was voluntary and completion of the survey was considered implied consent. Ethics approval was obtained from the relevant committees and baseline recruitment occurred between 2021 and 2022.

2.2 Measure

The survey included demographic characteristics (occupation, doctors’ specialty, department, length of practice, training received). Ten questions asked respondents about the degree to which they asked, advised, and actively supported current smokers and recent quitters over the prior 6 months (e.g., What proportion of patients [who smoked (daily or occasionally) OR recently quit] did you advise to quit smoking?). Response options involved 11 response options in percentage increments (e.g., 0%, 10%, 20%, etc. or N/A). Eight additional questions explored the specific benefits mentioned (i.e., What benefits of quitting smoking have you mentioned when advising patients to quit smoking?) and the reasons for nonprovision of smoking cessation care (e.g., What are the main reasons that you do not refer patients who smoke to Quitline?). Five multiple-choice questions were asked about the appropriateness of providing smoking cessation to cancer patients and the appropriate timing, including “Yes/No” questions about the training received.

2.3 Analysis

Descriptive statistics (numbers, proportions, means) were applied to demographic characteristics, smoking cessation practices, and training received. The survey items with a percentage as the response were categorized as “mostly” (70−90%) and “always” (100%) in the interest of reporting findings. Multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the association between demographic characteristics (occupation, doctors’ specialty, number of departments, length of practice, training received) and total smoking cessation practice score, which was used to indicate the likelihood of provision. This score (ranging 0–50) was determined by combining the responses to the 10 questions pertaining to the 3A's, such that a response of “100% of patients” to any of the 10 items equated to 5 points, “70−90% of patients” equated to 4 points, and so forth, as developed by the research team. Further analyses were performed to evaluate the association between the same demographic characteristics and a total mention of benefits score. This score (range of 0–6) was determined by combining the responses to the number of benefits indicated when answering the question, “What benefits of quitting smoking have you mentioned when advising patients to quit smoking?”.

The associations between demographic characteristics and total score were performed using fixed effects ordinal logistic regressions. Odds ratio estimates with 95% confidence intervals were obtained comparing odds of achieving a higher total score for each level of the covariates.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic Characteristics

The sample characteristics are provided in Table 1. Twenty survey responses were removed from the analysis because they did not include patient contact or clinical roles. The overall response rate was 36% (177/487). The majority were doctors (42%; 74/177) including nurse specialists (30%; 52/177), registered nurses (20%; 36/177), and allied health providers (8%; 15/177). HCPs worked across multiple tumor groups.

| Sample characteristics | Frequency (n) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Occupation | ||

| Doctor (medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, surgical oncologist, and hematologist) | 74 | 41.81% |

| Nurse (enrolled nurse and registered nurse) | 36 | 20.34% |

| Nurse specialists (cancer care coordinator, clinical nurse educator, nurse unit manager, clinical nurse consultant and clinical nurse specialist, nurse practitioners) | 52 | 29.83% |

| Allied health professional (radiation therapist, physiotherapist, psychologist, social worker, and pharmacist) | 15 | 8.47% |

| Doctors: Specialty | ||

| Medical oncology | 45 | 60.81% |

| Radiation oncology | 16 | 21.62% |

| Surgery + Hematology + Respiratory medicine | 13 | 17.56% |

| Nurses: Departmenta | ||

| One department | 42 | 47.73% |

| Multiple departments | 45 | 51.14% |

| Years of practicea | ||

| 0−11 months | 10 | 5.68% |

| 1−5 years | 47 | 26.70% |

| 6−10 years | 24 | 13.64% |

| 11−20 years | 56 | 31.82% |

| More than 20 years | 39 | 22.16% |

| Local health district | ||

| Metropolitan local health district | 78 | 44.07% |

| Regional or rural local health district | 99 | 55.93% |

| Received smoking cessation care training specific to the care of patients with cancer who smoke | ||

| No | 148 | 83.60% |

| Yes | 25 | 14.10% |

| Missing | 4 | 2.30% |

- a Missing one respondent.

3.2 Smoking Cessation Practices

The proportion of respondents who provided the 3A's smoking cessation model of care are provided in Table 2. Of the 177 respondents, 62% (n = 110) reported that they asked most or all patients who currently smoke in the last 6 months about their smoking status, 58% (103/177) of HCPs advised most or all patients to quit, 32% (56/174) of HCPs recorded the advice given, and 49% (84/174) of HCPs advised most or all patients of the cancer-specific benefits of quitting.

| Provision of 3As to current smokers across all specialties | 100% of patients | 70−90% | 40−60% | 10−30% | 0% | Not applicable to my role | Total | Missing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| ASK | ||||||||||||||

| Ask if smoke tobacco/other tobacco products or confirm smoking status from patient records | 66 | 37.29% | 44 | 24.86% | 16 | 9.04% | 23 | 12.99% | 15 | 8.47% | 13 | 7.34% | 177 | 0 |

| ADVISE | ||||||||||||||

| Advised daily or occasional smokers to quit smoking | 60 | 33.90% | 43 | 24.29% | 26 | 14.69% | 14 | 7.91% | 22 | 12.43% | 12 | 6.78% | 177 | 0 |

| Recorded the given advise to quit smoking (daily or occasionally) | 24 | 13.79% | 32 | 18.39% | 29 | 16.67% | 34 | 19.54% | 40 | 22.99% | 15 | 8.62% | 174 | 3 |

| Advised on cancer-specific benefits to daily or occasional smokers | 44 | 25.29% | 41 | 23.56% | 28 | 16.09% | 24 | 13.79% | 26 | 14.94% | 11 | 6.32% | 174 | 3 |

| Advised to use nicotine replacement therapy to quit smoking or manage withdrawal symptoms | 21 | 12.07% | 19 | 10.92% | 29 | 16.67% | 38 | 21.84% | 42 | 24.14% | 25 | 14.37% | 174 | 3 |

| Advised to use Champix (varenicline) | 2 | 1.16% | 5 | 2.89% | 9 | 5.20% | 22 | 12.72% | 98 | 56.65% | 37 | 21.39% | 173 | 4 |

| Advised to talk to Quitline | 26 | 14.77% | 19 | 10.80% | 29 | 16.48% | 38 | 21.59% | 50 | 28.41% | 14 | 7.95% | 176 | 1 |

| Advised to talk to a general practitioner or Aboriginal Health Service | 30 | 17.05% | 29 | 16.48% | 27 | 15.34% | 35 | 19.89% | 44 | 25.00% | 11 | 6.25% | 176 | 1 |

| ACT | ||||||||||||||

| Prescribe nicotine replacement therapy or refer to general practitioner for a prescription | 8 | 4.55% | 8 | 4.55% | 19 | 10.80% | 34 | 19.32% | 66 | 37.50% | 41 | 23.30% | 176 | 1 |

| Prescribe Champix (varenicline) or refer to general practitioner for Champix (varenicline) prescription | 2 | 1.15% | 4 | 2.30% | 9 | 5.17% | 15 | 8.62% | 94 | 54.02% | 50 | 28.74% | 174 | 3 |

| Referred to Quitline | 6 | 3.43% | 6 | 3.43% | 21 | 12.00% | 30 | 17.14% | 96 | 54.86% | 16 | 9.14% | 175 | 2 |

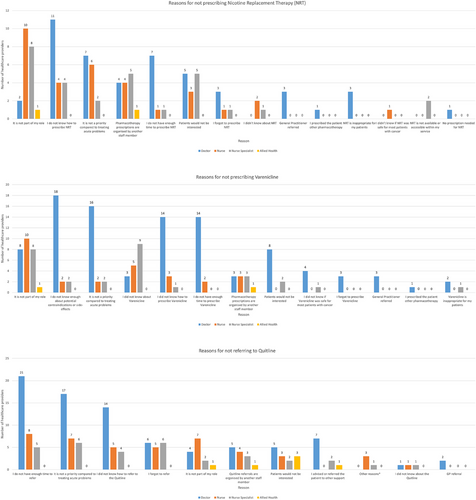

In relation to active referrals, only 9% (16/176) of HCPs prescribed NRT to most or all patients or referred them to a general practitioner for NRT prescription. Nurses (registered and specialist) indicated that prescribing NRT was not part of their role. Three percent (6/174) of HCPs prescribed varenicline to most or all patients or referred them to a general practitioner for varenicline. The main three reasons doctors indicated that they did not prescribe NRT and varenicline were because they “do not know how” (n = 11), “do not have enough time to prescribe(n = 7),” and it was “not a priority compared to treating acute problems” (n = 7) (Figure 1). Only 7% (12/175) of HCPs referred most or all patients to Quitline. Of the nurse specialists, 12% (6/51) indicated that they referred most or all patients to Quitline, while only 3% (1/36) of registered nurses reported referral.

3.3 Demographic Characteristics Associated with Differences in Smoking Cessation Practices

Table 3 provides the associations between demographic characteristics and the total smoking cessation core practice score. All components of the 3A's model were more likely to be provided by doctors compared to nurse specialists (OR: 2.55, 95% CI: 1.32, 4.95, p = 0.006), registered nurses (OR: 7.86, 95% CI: 3.64, 16.95, p < 0.001), and allied health providers (OR: 5.57, 95% CI: 1.90, 16.33, p = 0.002). Registered nurses were less likely to provide all components of the 3A's model compared to nurse specialists (OR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.14, 0.74, p = 0.008). HCPs were more likely to provide all components of the 3A's model if they had a longer time in practice (0−11 months vs. 11–20 years of practice; OR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.07−0.93, p = 0.039), and if they had received smoking cessation training (OR: 3.91, 95% CI: 1.80, 8.48, p = 0.001).

| Characteristic | Workflow comparison | Number of observations | Odds ratio | Contrast p-value | Type III p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Doctor versus nurse | 169 | 7.86 (3.64, 16.95) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Doctor versus allied health professional | 5.57 (1.90, 16.33) | 0.002 | |||

| Doctor versus nurse specialist | 2.55 (1.32, 4.95) | 0.006 | |||

| Nurse versus allied health professional | 0.71 (0.22, 2.26) | 0.558 | |||

| Nurse versus nurse specialist | 0.32 (0.14, 0.74) | 0.008 | |||

| Allied health professional versus nurse specialist | 0.46 (0.15, 1.41) | 0.173 | |||

| Doctors: Specialty | Medical oncology versus radiation oncology | 74 | 0.55 (0.19, 1.65) | 0.28 | 0.322 |

| Medical oncology versus surgery/hematology | 1.89 (0.60, 6.00) | 0.271 | |||

| Radiation oncology versus surgery/hematology | 3.43 (0.83, 14.17) | 0.087 | |||

| Nurses: Number of departments | One department versus multiple departments | 83 | 0.91 (0.42, 1.97) | 0.808 | 0.808 |

| Years of practice | 0−11 months versus 1–5 years | 168 | 0.15 (0.04, 0.53) | 0.004 | 0.018 |

| 0−11 months versus 6–10 years | 0.26 (0.07, 1.01) | 0.051 | |||

| 0−11 months versus 11–20 years | 0.26 (0.07, 0.93) | 0.039 | |||

| 0−11 months versus more than 20 years | 0.12 (0.03, 0.47) | 0.002 | |||

| 1−5 years versus 6–10 years | 1.76 (0.78, 4.01) | 0.173 | |||

| 1−5 years versus 11–20 years | 1.77 (0.88, 3.56) | 0.109 | |||

| 1−5 years versus more than 20 years | 0.84 (0.39, 1.82) | 0.656 | |||

| 6−10 years versus 11–20 years | 1.00 (0.44, 2.29) | 0.995 | |||

| 6−10 years versus more than 20 years | 0.48 (0.20, 1.16) | 0.103 | |||

| 11−20 years versus more than 20 years | 0.48 (0.22, 1.04) | 0.062 | |||

| Received training | Yes versus no | 165 | 3.91 (1.80, 8.48) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

3.4 Training

A quarter (24%; 41/174) of respondents had received smoking cessation care training generally (e.g., in-service, training video) and only 15% (25/173) received smoking cessation care training specific to the care of patients with cancer.

3.5 Appropriateness of Smoking Cessation Care (3A's Brief Model)

Most respondents (89%; 158/177) indicated on a multiple-choice question that the most appropriate time for the provision of smoking cessation care was at diagnosis, followed by during treatment (64%; 113/177) and after treatment (53%; 93/177).

Most respondents indicated that smoking cessation care was appropriate for patients with all cancer types (average 98.5%) and patients with curable disease (average 99.5%); however, there appeared to be slightly fewer nurse specialists agreeing to the appropriateness for patients with nontobacco-related cancers (94%; 49/52). Patients with incurable or metastatic disease were less likely to be considered appropriate by all specialties (average 75.7%).

3.6 Follow-Up

Twenty-nine percent (50/175) of respondents mostly or always ask again about smoking status. Nearly half of doctors (46%; 37/74) mostly or always follow-up, which is less for nurses (registered and specialists; 15%; 13/88) and allied health providers (0%). Less than a quarter mostly or always follow-up about whether patients have engaged with Quitline or used pharmacotherapy (6%, 11/174; 12%, 21/173, respectively).

3.7 Providing Cancer-Specific Advice on the Benefits of Quitting

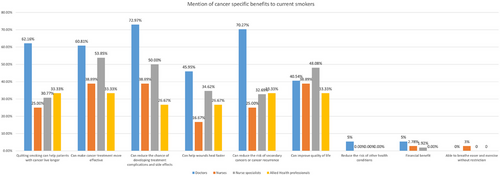

The HCPs who indicated they advised 10% or more of their patients of cancer-specific benefits of stopping smoking were asked to specify which cancer-specific benefits they mentioned to their patients who smoke (Figure 2).

3.8 Demographic Characteristics Associated With Cancer-Specific Advice Provision

Table 4 provides the associations between demographic characteristics and the total number of benefits mentioned by HCPs, which indicates the likelihood of providing all six of the benefits identified. There was an overall difference in the amount of cancer-specific advice provided between occupation type (type III p < 0.001) and years of practice (type III p = 0.021). There was no difference in total practice score between different doctor specialties (medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgery/hematology) (type III p = 0.147), between working in one or multiple departments as a nurse (type III p = 0.612) or receiving training (type III p = 0.159).

| Characteristic | Workflow comparison | Number of observations | Odds ratio | Contrast p-value | Type III p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Doctor versus nurse | 177 | 4.77 (2.25, 10.08) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Doctor versus allied health professional | 4.71 (1.65, 13.42) | 0.004 | |||

| Doctor versus nurse specialist | 2.40 (1.25, 4.60) | 0.009 | |||

| Nurse versus allied health professional | 0.99 (0.32, 3.08) | 0.984 | |||

| Nurse versus nurse specialist | 0.50 (0.23, 1.12) | 0.094 | |||

| Allied health professional versus nurse specialist | 0.51 (0.17, 1.51) | 0.223 | |||

| Doctors: Specialty | Medical oncology versus radiation oncology | 74 | 0.36 (0.13, 1.01) | 0.053 | 0.147 |

| Medical oncology versus surgery/hematology | 1.20 (0.32, 4.50) | 0.784 | |||

| Radiation oncology versus surgery/hematology | 3.29 (0.73, 14.90) | 0.119 | |||

| Nurses: Number of departments | One department versus multiple departments | 87 | 1.22 (0.57, 2.62) | 0.612 | 0.612 |

| Years of practice | 0−11 months versus 1–5 years | 176 | 0.30 (0.09, 0.97) | 0.044 | 0.021 |

| 0−11 months versus 6–10 years | 0.24 (0.07, 0.85) | 0.028 | |||

| 0−11 months versus 11–20 years | 0.63 (0.19, 2.03) | 0.436 | |||

| 0−11 months versus more than 20 years | 0.24 (0.07, 0.82) | 0.024 | |||

| 1−5 years versus 6–10 years | 0.80 (0.35, 1.84) | 0.595 | |||

| 1−5 years versus 11–20 years | 2.11 (1.06, 4.22) | 0.035 | |||

| 1−5 years versus more than 20 years | 0.81 (0.38, 1.74) | 0.582 | |||

| 6−10 years versus 11–20 years | 2.64 (1.13, 6.19) | 0.025 | |||

| 6−10 years versus more than 20 years | 1.01 (0.41, 2.51) | 0.979 | |||

| 11−20 years versus more than 20 years | 0.38 (0.18, 0.83) | 0.016 | |||

| Received training | Yes versus no | 173 | 1.73 (0.80, 3.71) | 0.159 | 0.159 |

Doctors were more likely to mention a greater number of benefits to quitting smoking to patients in comparison to nurse specialists (OR: 2.40, 95% CI: 1.25, 4.60, p = 0.009), registered nurses (OR: 4.77, 95% CI: 2.25, 10.08, p < 0.001), and allied health providers (OR: 4.71, 95% CI: 1.65, 13.42, p = 0.004). HCPs with a longer time in practice were more likely to provide a greater number of benefits to patients (0−11 months vs. 11–20 years of practice; OR: 0.24, 95% CI: 0.07−0.82, p = 0.024).

4 Discussion

This study provides a snapshot of the provision of smoking cessation practices in nine hospital-based cancer centers, covering two states of Australia. Unlike some other reports [17, 21], this study included responses from nurses and allied health providers and looked at the depth and breadth of the cessation support provided. Overall, there was variation in the provision of smoking cessation care practices across HCPs.

The starkest difference was that doctors were seven times more likely to complete all parts of the 3A's model of care (Ask, Advise, Act) compared to registered nurses. Of the doctors in the study, oncologists were the primary responders (82%). Australian data [17] indicated that oncologists were asking patients about their smoking status at the initial consultation (90%) and advising cessation (70−72%). However, less than one-fifth of oncologists regularly discussed cessation medication options (15−17%) or referred to a behavioral support program (15−22%; e.g., Quitline) [17]. Rates of referral to NRT (13%) were slightly lower in the current study and Quitline referral (5%).

A longer time in practice was positively associated with smoking cessation care practices. However, Warren and colleagues found that this was only true for the two initial parts of the 3A's model: asking about tobacco use/quitting and advising people who smoke to stop; but not significantly associated with discussing medications or actively treating patients [21]. Such findings are consistent with the fact that medication management would only be carried out by those who have received training. Often, NRT and varenicline training is provided early in oncologists’ training, and upskilling in pharmacotherapy is rare, with more senior oncologists receiving training only if they have an active interest in the topic. The majority of Australian oncologists have reported that they require more training (57−67%) and trainees would benefit from greater smoking cessation training (67−75% of medical and radiation oncologists) [17].

The most-cited reason for doctors not prescribing smoking cessation pharmacotherapies was a lack of knowledge. A lack of knowledge about pharmacotherapies can be addressed via training, including how pharmacotherapies can be used in conjunction with anticancer treatments. However, as oncology HCPs are not likely to frequently encounter patients who are eligible and interested in pharmacotherapies, refresher training and ready access to advice or support (e.g., via smoking cessation clinicians or addiction specialists) are likely to be important. Nurses largely reported that prescribing pharmacotherapies was outside of their role or someone else's role. Only a quarter of HCPs reported receiving any type of smoking cessation training in our study. Of those who did, their provision of the 3A's model was greater than those who received no training. Routine delivery of smoking cessation care in oncology requires upskilling of current hospital staff about both providing brief advice and prescribing pharmacotherapies for cessation. Nurses may benefit from training aimed to provide information which allows them to support the use of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation.

The equal second most-cited reasons for doctors not prescribing smoking cessation pharmacotherapies were insufficient time to prescribe and it being a low priority compared to treating acute problems. Nurses also reported pharmacotherapies were not prescribed due to being a low priority. Perceived lack of time and prioritization are closely related issues. It may be helpful to oncology clinicians if studies were to directly explore the relationship between the use of pharmacotherapy and treatment outcomes for people who report smoking near the time of a cancer diagnosis.

The appropriateness of smoking cessation care for cancer patients across the cancer care continuum also needs to be addressed. HCPs in the current study and elsewhere are more likely to address smoking behaviors, follow-up, and discuss medication options with curative cancer patients than they are to address these with palliative cancer patients [22]. Nevertheless, HCPs need to provide opportunities for all cancer patients to understand the benefits of quitting, even for patients with metastatic cancer where there can be survival benefits [23, 24], or in a palliative care setting where smoking cessation can improve a patient's quality of life (e.g., decreased shortness of breath, increased sense of accomplishment) [25]. It must be acknowledged that while the evidence for benefits in these settings is sparse, it suggests that such patients should be actively supported to quit, should they wish to do so.

The type of advice provided to patients about quitting also appeared to differ by HCP role. In general, doctors appeared to emphasize the benefit of quitting on treatment outcomes and overall survival, while nurses and allied health providers advised on the benefits to quality of life. Government and healthcare institutional guidelines [12, 26] recommend personalizing the benefits of quitting to the patient's situation and discussing the importance of quitting for cancer treatment. Personalization of the benefit of quitting to the cancer context and the patient's diagnosis has direct relevance to the needs and concerns of the patient (e.g., minimizing shortness of breath, increasing the ability to taste, reducing the toxicity of cancer treatment). In comparison to no intervention, advice to quit on medical grounds increased the frequency of quit attempts (risk ratio [RR] 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.16–1.33) and increased long-term abstinence by 47% ([RR] 1.47, 95% CI:1.24–1.75) according to a systematic review assessing the effects of physician brief smoking advice [27]. Nevertheless, referring to behavioral support or offering medication generated more quit attempts than advising to quit on medical grounds, which suggests that all components of the 3A's need to be offered to promote quit attempts (i.e., advising and acting). There are data to suggest that assessing a patient's willingness to quit without offering active referral to behavioral or medication support averts people who would otherwise be interested in quitting [27].

4.1 Limitations

The cross-sectional design of the study was an efficient and effective way to evaluate and gather a large sample of HCPs working across nine hospitals in two states of Australia. The higher response rates at large regional and rural centers have skewed the sample somewhat away from the metropolitan setting. Yet, at the same time, the cross-sectional design means that associations cannot be interpreted causally [28]. Other limitations include the low response rate. The low survey response rate raises the likelihood of responder bias, such that survey respondents are likely to be those who are more interested in smoking cessation care. In addition, as survey recruitment was part of the baseline of an intervention trial, there may also be responder bias in the direction of reporting higher levels of cessation care. That is, the data presented here may be an underestimation (or inflation) of the true provision of cessation care. Survey questions had the response option, “N/A,” which might have increased the number of respondents who chose this option because they do not consider the behavior important or are yet to engage in that behavior, leading further to underestimating the desired response. The smoking cessation practice total score is indicative of the provision of all aspects of the 3A's model of care, including tasks that most nurses would consider not applicable to their role (e.g., medication prescription), albeit nurse practitioners, represented a small sample. As such, the regressions are only indicative of the overall smoking cessation care provided.

5 Conclusion

This study confirms that the entirety of the recommended [12] active smoking cessation care is not provided to many patients in a number of oncology settings in Australia. Greater experience and training in smoking cessation care are related to the delivery of cessation care. Therefore, smoking cessation care training—including referral for behavioral support—should continue to be a focus of intervention efforts. Training in prescribing pharmacotherapies (for doctors) or supporting the use of pharmacotherapies (for nurses) is a particular “gap” which warrants attention. Doctors and nurses differ in their level of engagement with smoking cessation care and how they present the potential benefits of cessation. This role delineation seems appropriate and should be considered in the development of site-specific models of care and in training provision.

Acknowledgments

This project is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1169324); Cancer Council Australia; Cancer Council Victoria; Quit Victoria. Thank you to Stuart Szwec and Daniel Barker for statistical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.