Association of optimism and social support with health-related quality of life among Australian women cancer survivors – A cohort study

Julie Byles and Karen Canfell are Co-senior authors.

Abstract

Aim

Large-scale studies investigating health-related quality of life (HRQL) in cancer survivors are limited. This study aims to investigate HRQL and its relation to optimism and social support among Australian women following a cancer diagnosis.

Methods

Data were from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health, a large cohort study (n = 14,715; born 1946–51), with 1428 incident cancer cases ascertained 1996–2017 via linkage to the Australian Cancer Database. HRQL was measured using the Short Form-36 (median 1.7 years post-cancer-diagnosis). Multivariable linear regression was performed on each HRQL domain, separately for all cancers combined, major cancer sites, and cancer-free peers.

Results

Higher optimism and social support were significantly associated with better HRQL across various domains in women with and without a cancer diagnosis (p < 0.05). Mean HRQL scores across all domains for all cancer sites were significantly higher among optimistic versus not optimistic women with cancer (p < 0.05). Adjusting for sociodemographic and other health conditions, lower optimism was associated with reduced scores across all domains, with greater reductions in mental health (adjusted mean difference (AMD) = −11.54, p < 0.01) followed by general health (AMD = −11.08, p < 0.01). Social support was less consistently related to HRQL scores, and following adjustment was only significantly associated with social functioning (AMD = −7.22, p < 0.01) and mental health (AMD = −6.34, p < 0.01).

Conclusions

Our findings highlight a strong connection between optimism, social support, and HRQL among cancer survivors. Providing psychosocial support and addressing behavioral and socioeconomic factors and other health conditions associated with optimism and social support may improve HRQL.

1 INTRODUCTION

With advancements in the early detection and treatment of cancer in recent decades, cancer survivors are a large and growing population worldwide.1 In Australia alone, over 1.1 million people live with current cancer or a history of cancer, with 70% surviving at least five years after diagnosis.2 Despite many survivors being able to live a healthy and productive life, many experience a range of health complications as a consequence of cancer diagnosis and treatment. These can include diagnosis-related stressors, treatment burden, fear of recurrence, the need (or desire) to resume roles or daily activities, and uncertainty about current and future health conditions and life events. Such challenges can have a lasting negative impact on survivors’ health and emotional well-being. There is a lack of studies that assess long-term health outcomes using patient-reported outcome data.3

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) encompasses patients’ overall perception of their health and well-being across several dimensions, including physical, emotional, social, and psychological functions.4 Optimising HRQL is one of the key goals of cancer treatment and supportive care. In oncology research, HRQL is widely used as an important outcome in observational studies, interventions, and surveillance of health and well-being. Previous studies among selected cancer populations have suggested that cancer patients are more likely to experience poorer physical and mental functioning compared to the general population,5 and several sociodemographic,6 behavioral,7 and clinical factors8 can negatively influence their HRQL. Although a growing number of studies focused on the determinants of HRQL among cancer survivors, most have primarily concentrated on disease- and treatment-related variables and prognostic factors.9 Only a few studies have examined the psychological and social factors influencing HRQL, such as ‘optimism’ and social support.10, 11

Optimism, defined as the general expectation/belief that favorable outcomes will happen, is a crucial psychological asset that acts as a personal resource for maintaining a positive mood and overcoming adversity. This attribute plays an essential role across the entire lifespan in healthy development, resilience, and aging well among both the general population and medically ill patients, 12, 13 In the context of cancer, optimism has been shown to provide numerous benefits regarding physical, social, and emotional well-being.10, 14 Social support is another psychosocial variable that refers to the perceived psychological and material resources received from interpersonal relationships when someone needs help or support.15 Previous studies have shown that increased social support is associated with decreased cancer-related distress and better HRQL among cancer survivors.16, 17 Optimistic people are more likely to develop effective social relationships than those who are not optimistic.14 Therefore, they are more likely to receive greater social support, improving their QL.10 However, how these two variables work together in relation to HRQL domains in cancer survivors remains unclear.

The current evidence on psychosocial factors relating to HRQL among cancer survivors is limited and based on small or moderate sample sizes, and cross-sectional samples of selected cancer patients, and mostly does not consider time since diagnosis or phase of care. To our knowledge, no prospective cohort study has investigated the relation of optimism and social support with HRQL in cancer survivors. This study aims to assess HRQL in a cohort of Australian women cancer survivors and examines the association of psychosocial factors and HRQL domains, focusing on the roles of optimism and social support in relation to HRQL outcomes.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data and sample

The study used survey data from the 1946–51 birth cohort of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH), collected between 1996 (cohort aged 45–50 years) and 2019 (cohort aged 68–73 years) and incident cancer information from the linked Australian Cancer Database (ACD) between 1996 and 2017. Details about the ALSWH cohort, survey waves, and attrition rates have been published elsewhere.18 Briefly, participants were randomly selected using the Medicare Australia database, with oversampling from remote/rural areas. In total, 13,714 women completed a self-reported postal questionnaire at baseline (Survey 1, 1996; response rate 52%–56%). These women were first followed up in 1998 and thereafter followed up every three years. There has been a high retention rate (around 80%) between subsequent follow-ups, with 7956 women completing Survey 9 (8th follow-up) in 2019. There were 1171 deaths in the cohort between 1996 and 2019.

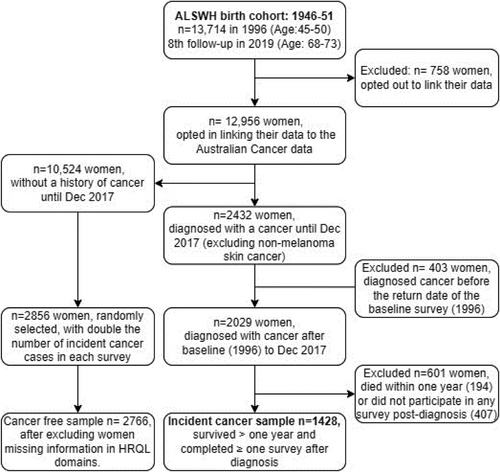

The cancer case sample included 1428 women diagnosed with primary invasive cancer after the baseline survey until December 2017 (as of the latest available data), who survived at least one year and completed at least one survey after cancer diagnosis. Women diagnosed with cancer before completion of the baseline survey (n = 403), those who did not complete any survey after a cancer diagnosis (n = 407), and those who died within one year of cancer diagnosis (n = 194) were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1) We excluded women who did not complete any survey after a cancer diagnosis because no data was available to assess their HRQL. Previous studies reported that those who missed surveys were likely to have poorer health than those who continued the survey.19, 20 The cancer-free control sample included 2766 women, randomly selected from those without a current or history of cancer who participated in different surveys, with almost double the number of incident cancer diagnoses recorded between subsequent surveys.

The ALSWH study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland. Access to the survey data was approved by the ALSWH data access committee. Approval for accessing the linked Australian Cancer Database was obtained separately for each state or territory, which the ALSWH data custodian managed as part of the approval of this study.

2.2 Ascertainment of cancer cases

Cancer cases between 1996 and 2017 were ascertained from the linked ACD data using the International Classification of Disease 10 codes (Table S1) and were categorized into six major groups: breast, melanoma of the skin, digestive organs, female genital organs and blood and lymphatic systems, and all remaining cancer types as other cancers.

2.3 Measures

All variables used in this study were obtained from the first survey completed after cancer diagnosis (median: 1.7 years with interquartile range: 0.8–2.4) and those in the control sample were from the respective survey they were selected.

2.4 Health-related QL

HRQL was assessed using the Medical Outcome Study (MOS) Short Form-36 (SF-36) self-reported 36-item questionnaire across eight domains/domains, including physical functioning, social functioning, mental health, general health, vitality, bodily pain, role emotional, and role physical.21 Raw scores were calculated as the sum of scale items in each domain and transformed to 0–100 using the formula: (Raw score—minimum possible raw score)/possible raw score range × 100, with higher scores indicating better outcomes. Role emotional and role physical domains were not included in the current analysis because of the non-normality/categorical nature of the derived score.

2.5 Social support and optimism

Social support was assessed using the 19-item MOS social support index (SSI)22 in all surveys except for Survey 3, where the 6-item abbreviated MOS SSI was used.15 The mean score of the MOS SSI items (5-point Likert scale) was calculated and categorized as support “all the time” (score > 4), “most of the time” (3 < score < = 4), “some of the time” (2 < score < = 3), “none or little of the time” (score < = 2). These four groups were merged into two broad groups ‘high’ who received support all or most of the time and ‘low’ who received support ‘some/little/none of the time’. Optimism was assessed using the 6-item Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R).23 Items are summed to produce a LOT-R score (range 0–24); higher scores indicate a more optimistic outlook. Based on the quartiles of the summed score, participants were categorized into four groups with a score < 13.5: very low, 13.5≤score < 16: moderately low, 16.0≤score < 18: moderately high, and a score≥18: very high optimism.24 For analytical purposes, very low and moderately low were merged into one group, ‘low optimism/not optimistic’, and the other two groups into ‘high optimism/optimistic’.

2.6 Demographic, behavioral, and health factors

Demographic characteristics included age at cancer diagnosis, area of residence, marital status, country of birth, educational qualifications, and ability to manage available income. Behavioral factors included smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and physical exercise.10 Clinical/health factors included time since diagnosis of cancer and major health conditions other than cancer, including diabetes, arthritis, osteoporosis, heart disease, stroke, hypertension, asthma, kidney disease, low iron level, and bronchitis. The number of other health conditions was categorized as ‘no other conditions’, ‘1–2 other conditions, and > 2 other conditions. Detailed categorization of these variables is provided in Table 1.

| Characteristics | n† | % | Characteristics | n† | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (Mean, SD) | 59.0 (6.3) | – | Body mass index (BMI) | ||

| Time since diagnosis | Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 21 | 1.6 | ||

| ≤1 year | 432 | 30.2 | Normal (18.5 ≤BMI < 25) | 471 | 35.3 |

| 1–2 year | 472 | 33.1 | Overweight (25 ≤BMI < 30) | 438 | 32.8 |

| 2–3 year | 525 | 36.7 | Obese (BMI≥30) | 406 | 30.4 |

| Median (IQR) | 1.7 (0.8-2.4) | – | Other health condition | ||

| Cancer site | 0 | 436 | 30.5 | ||

| Breast | 635 | 44.5 | 1–2 | 719 | 50.4 |

| Melanoma of skin | 208 | 14.5 | > 2 | 273 | 19.2 |

| Digestive organ | 153 | 10.7 | Physical activity | ||

| Female genital organs‡ | 124 | 8.7 | Sedentary | 290 | 22.1 |

| Blood and lymphatic system§ | 99 | 6.9 | Low | 330 | 25.2 |

| All other cancer | 209 | 14.6 | High | 420 | 32.0 |

| Area of residence | Low | 330 | 25.2 | ||

| Major cities | 561 | 39.3 | Smoking status | ||

| Inner regional | 562 | 39.4 | Never smoked | 838 | 61.0 |

| Remote/outer regional | 305 | 21.4 | Ex-smoker | 415 | 30.2 |

| Country of birth | Current smoker | 122 | 8.9 | ||

| Australia | 1113 | 78.5 | Social support | ||

| Other English-speaking countries | 179 | 12.6 | All the time | 784 | 57.5 |

| All other countries | 126 | 8.9 | Most of the time | 360 | 26.4 |

| Marital status | Some of the time | 154 | 11.3 | ||

| Married/De facto | 1019 | 71.4 | None or little of the time | 65 | 4.8 |

| Never married/divorced/separated/widowed | 409 | 28.6 | Optimism | ||

| Education | Very low | 339 | 25.4 | ||

| No formal | 195 | 13.7 | Moderately low | 351 | 26.3 |

| < = 12 years of education | 726 | 50.8 | Moderately high | 340 | 25.4 |

| > 12 years of education | 507 | 35.5 | Very high | 330 | 22.7 |

| Managing available income | |||||

| Difficult or impossible | 488 | 35.7 | |||

| Easy or not too bad | 879 | 64.3 |

- † Only the complete cases are reported. The frequencies in some variables may not add up to the total sample size n = 1428.

- † Included esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colorectal, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

- ‡ Included the cervix, uterus, ovary, vulva, and vagina.

- § Included Hodgkin/non-Hodgkin lymphoma, immunoproliferative, myeloma, and leukemia.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The distribution of cancer survivors by demographic, behavioral, and health factors was explored initially using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for discrete variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Mean scores for each HRQL domain by the levels of optimism and social support were calculated and compared using two-sample t-tests, for all cancers combined and for each cancer site separately. Multivariable linear regressions were performed separately for each domain, separately for all cancer combined, major cancer sites, and cancer-free controls to estimate the adjusted mean differences (AMD) or regression coefficients and 95% confidence interval (CI) for optimism, social support, and their interactions. All variables were entered into the model by a combination of forward stepwise selection (with p < 0.20 to stay in the model) and changes in the estimation criteria, including Akaike Information Criteria and Bayesian Information Criteria.25 BMI and smoking status were not included in the model, given the association with other variables, for example, smoking with other health conditions and obesity with physical activity. Simple effect analysis was used to follow up significant interaction of optimism and social support, enabling how the levels of one variable interact with the levels of another to influence the outcome variable. Residual plots against predicted values were checked to assess the fit of the models. Sensitivity analysis was performed with multiple imputations of the missing covariate information to examine potential variation in the results of the multivariable linear regression. We also performed separate analyses adjusting for BMI and smoking variables in the model to see whether any changes in the effect of optimism and social support. All analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

3 RESULTS

Of 1428 women cancer survivors included in the analysis, 44% were diagnosed with breast cancer, followed by melanoma (15%), digestive organs (11%), female genital organs (9%), blood and lymphatic system (7%) and all other cancers (15%, Table 1). The majority of survivors lived outside of major cities (60%), were married/de facto (71%), were able to easily or not too badly manage on available income (64%), and had at least one other health condition (70%). Approximately 30% of participants completed the survey within the first year of diagnosis, 33% in the second year, and 37% in the third year.

3.1 HRQL by optimism and social support

Mean scores across all HRQL domains significantly differed by the levels of optimism, with optimistic survivors likely to experience better HRQL (Table 2). For example, the mean score for optimistic survivors versus those not optimistic was 77 versus 66 (p < 0.01) for physical functioning. Those who reported receiving low social support had lower mean scores across all HRQL domains compared to those who received high social support, with significant differences in social functioning (77 vs. 64, p < 0.01) and mental health (76 vs. 64, p < 0.01) domains. Considering each cancer site separately, optimistic women who received high social support had a higher mean score across all domains. However, the differences for social support were not significant at p < 0.05 in various domains for most cancer sites.

| Mean score (SE) by social support | Mean score (SE) by optimism | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer sites | HRQL subscale | High | Low | p-value | High | Low | p-value |

| All cancers combined (n = 1428) | PF | 72.6(0.7) | 67.7(1.7) | p < 0.01 | 76.9(0.8) | 66.7(1.0) | p < 0.01 |

| SF | 78.0(0.8) | 64.9(1.8) | p < 0.01 | 81.0(0.9) | 68.7(1.1) | p < 0.01 | |

| MH | 76.0(0.5) | 65.2(1.2) | p < 0.01 | 84.2(0.5) | 66.8(0.7) | p < 0.01 | |

| GH | 62.4(0.7) | 55.2(1.6) | p < 0.01 | 68.0(0.8) | 54.0(0.9) | p < 0.01 | |

| BP | 62.9(0.7) | 59.6(1.7) | p = 0.08 | 67.7(0.9) | 57.0(0.9) | p < 0.01 | |

| VT | 56.5(0.7) | 48.6(1.5) | p < 0.01 | 62.1(0.9) | 47.8(0.8) | p < 0.01 | |

| Breast (n = 635) | PF | 74.2(0.9) | 69.8(2.3) | p = 0.08 | 77.4(1.1) | 69.3(1.4) | p < 0.01 |

| SF | 77.4(1.2) | 67.1(2.7) | p < 0.01 | 82.4(1.3) | 68.9(1.7) | p < 0.01 | |

| MH | 75.6(0.8) | 66.4(1.9) | p < 0.01 | 81.1(0.8) | 66.5(1.1) | p < 0.01 | |

| GH | 63.4(0.9) | 55.0(2.3) | p < 0.01 | 67.7(1.2) | 55.1(1.3) | p < 0.01 | |

| BP | 62.4(1.1) | 59.3(2.4) | p = 0.23 | 67.0(1.3) | 56.3(1.4) | p < 0.01 | |

| VT | 56.8(0.9) | 49.6(2.3) | p < 0.01 | 62.4(1.1) | 47.9(1.3) | p < 0.01 | |

| Melanoma of the skin (n = 208) | PF | 79.6(1.5) | 75.0(3.8) | p = 0.26 | 84.2(1.6) | 73.8(2.2) | p < 0.01 |

| SF | 86.0(1.6) | 66.2(4.4) | p < 0.01 | 88.9(1.9) | 76.0(2.4) | p < 0.01 | |

| MH | 79.2(1.2) | 68.2(3.4) | p < 0.01 | 84.0(1.2) | 70.0(1.8) | p < 0.01 | |

| GH | 70.7(1.4) | 68.7(3.6) | p = 0.60 | 77.9(1.5) | 62.0(2.0) | p < 0.01 | |

| BP | 67.2(1.8) | 62.2(4.5) | p = 0.31 | 73.5(2.1) | 60.1(2.6) | p < 0.01 | |

| VT | 63.1(1.6) | 53.1(4.3) | p = 0.03 | 68.5(1.9) | 53.4(2.2) | p < 0.01 | |

| Digestive organ (n = 153) | PF | 65.2(2.3) | 67.6(5.4) | p = 0.69 | 68.6(2.8) | 62.8(3.1) | p < 0.19 |

| SF | 72.4(2.4) | 62.5(5.9) | p = 0.15 | 75.5(3.0) | 67.0(3.3) | p < 0.07 | |

| MH | 75.1(1.3) | 63.4(3.8) | p < 0.01 | 80.0(1.4) | 68.3(2.1) | p < 0.01 | |

| GH | 57.9(2.0) | 55.7(4.5) | p = 0.71 | 61.4(2.7) | 54.2(2.8) | p < 0.07 | |

| BP | 60.1(2.1) | 65.6(5.9) | p = 0.31 | 62.3(3.1) | 58.9(3.0) | p = 0.52 | |

| VT | 54.4(1.8) | 47.6(4.2) | p = 0.18 | 57.4(2.6) | 48.9(2.4) | p = 0.02 | |

| Female genital (Cervix, uterus, ovary, vulva, and vagina, n = 124) | PF | 72.0(2.1) | 66.9(6.0) | p = 0.42 | 77.6(2.2) | 63.8(3.4) | p < 0.01 |

| SF | 76.6(2.5) | 67.2(6.3) | p = 0.18 | 79.1(3.3) | 70.7(3.7) | p = 0.08 | |

| MH | 78.0(1.7) | 66.8(2.9) | p < 0.01 | 83.1(1.7) | 67.7(2.4) | p < 0.01 | |

| GH | 62.0(2.3) | 52.9(5.6) | p = 0.14 | 69.6(2.5) | 49.2(3.2) | p < 0.01 | |

| BP | 64.6(2.1) | 56.6(5.9) | p = 0.21 | 68.4(2.4) | 56.8(3.1) | p < 0.01 | |

| VT | 55.7(2.2) | 46.9(5.1) | p = 0.12 | 61.1(2.6) | 46.1(2.9) | p < 0.01 | |

|

Blood and lymphatic system (Hodgkin/non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma, and leukemia, n = 99) |

PF | 67.3(2.9) | 55.6(6.2) | p = 0.10 | 71.0(3.9) | 59.1(3.5) | p < 0.05 |

| SF | 68.5(3.6) | 48.6(6.2) | p < 0.01 | 70.9(5.1) | 59.1(4.1) | p = 0.07 | |

| MH | 75.0(1.8) | 58.7(3.8) | p < 0.01 | 80.0(2.3) | 65.3(2.2) | p < 0.01 | |

| GH | 53.6(2.7) | 38.9(5.0) | p < 0.05 | 57.4(3.9) | 43.7(2.9) | p < 0.01 | |

| BP | 61.8(2.9) | 44.9(5.3) | p < 0.01 | 65.8(4.2) | 52.4(3.3) | p < 0.05 | |

| VT | 53.2(2.6) | 36.1(5.1) | p < 0.01 | 57.4(3.8) | 42.8(2.8) | p < 0.01 | |

| Other (n = 209) | PF | 65.8(2.1) | 55.6(5.3) | p = 0.07 | 73.4(2.5) | 56.9(2.8) | p < 0.01 |

| SF | 72.9(2.2) | 60.7(4.1) | p < 0.01 | 77.3(2.9) | 65.5(2.7) | p < 0.01 | |

| MH | 73.4(1.4) | 57.8(3.2) | p < 0.01 | 79.5(1.5) | 63.1(1.9) | p < 0.01 | |

| GH | 53.5(1.8) | 47.5(4.5) | p = 0.22 | 64.3(2.4) | 43.6(2.3) | p < 0.01 | |

| BP | 59.6(2.0) | 57.1(5.3) | p = 0.62 | 65.3(2.6) | 53.7(2.6) | p < 0.01 | |

| VT | 51.8(1.6) | 43.1(3.9) | p = 0.03 | 59.2(2.3) | 42.4(2.0) | p < 0.01 | |

- Abbreviations: BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; MH, mental health; PF, physical functioning; SF, social functioning; VT, vitality.

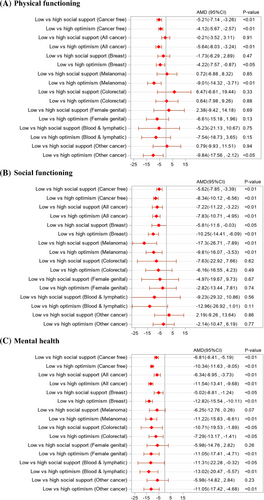

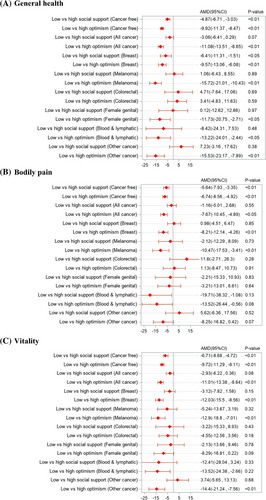

Results from the multivariable linear regressions reveal that women with low optimism had significantly lower scores in HRQL across all domains than those with higher optimism, for all cancers combined and those without cancer (Figure 2 and Figure 3). A significant relationship between low optimism and lower HRQL was also seen separately for some cancer sites (p < 0.05). For example, low optimism was associated with lower mental health scores for breast cancer (AMD = −12.82, 95%CI: −15.54, −10.11), melanoma (AMD = −11.22, 95%CI: −15.83, −6.61), digestive organs (AMD = −7.29, 95%CI: −13.17, −1.41), female genital (AMD = −11.05, 95%CI: −17.41, −4.71), blood and lymphatic (AMD = −13.02, 95%CI: −20.47, −5.57), other cancers (AMD = −11.05, 95%CI: −17.42, −4.68), and cancer-free controls (AMD = −10.34, 95%CI: −11.63, −9.05). While low social support was significantly associated with lower HRQL across all domains among women without cancer, the association was only significant in social functioning (AMD = −7.22, 95%CI: −11.22, −3.22) and mental health (AMD = −6.34, 95%CI: −8.95, −3.73) among cancer survivors, specifically, women with any cancer and women with breast cancer.

Considering the joint relation of optimism and social support to HRQL, no significant interaction was observed in any domain for women without cancer, suggesting largely independent relationships with the outcome (Table S2). However, a significant interaction effect was observed for women with cancer in some domains, with stronger relationships between low optimism and reduced physical functioning (p < 0.05), worse mental health (p < 0.05), and greater bodily pain (p < 0.01) in the presence of low social support (compared to high social support).

3.2 Relationship of other factors to HRQL

Several sociodemographic, behavioral, and a number of other health conditions were significantly associated with HRQL domains (Table S3). Time since cancer diagnosis was significantly associated with increased HRQL across all domains except for physical functioning (p < 0.05). For example, compared to those who completed the survey questions in the first year of cancer diagnosis, the adjusted mean social functioning score was 11.2 points and 14.9 points lower among those who completed the survey in the second and third year since diagnosis, respectively. While the area of residence, marital status, and educational qualifications were not significant at p < 0.05 for most domains among cancer survivors, ‘difficult or impossible’ compared to ‘easy or not too bad’ in managing available income was significantly associated with decreased HRQL across all domains (p < 0.01). Compared to moderate or high physical activity, low or no physical activity was significantly associated with lower scores across all domains, with a greater decline in social functioning (AMD = −12.1, 95%CI = −14.84, −9.35) followed by vitality (AMD = −10.4, 95%CI = −12.75, −8.04).

The results of the sensitivity analysis with multiple imputations for missing data are presented in Table S4. The direction and magnitude of the association observed with and without imputation were almost identical to that in the main analysis. Furthermore, the results of sensitivity analysis adjusting for the BMI and smoking status in the model are presented in Table S5 and reveal that the effect of optimism and social support is almost similar without including these variables.

4 DISCUSSION

This is the first prospective cohort study, to our knowledge, that investigated the relationship between optimism and social support with HRQL domains among Australian women following a cancer diagnosis and cancer-free peers simultaneously. The results show that higher optimism was associated with better HRQL across all domains for both women with and without cancer, adjusting for demographic, behavioral, and other health conditions. This is consistent with previous studies reporting optimism being positively associated with HRQL, spiritual coping, mental health, and well-being among cancer patients.10, 14, 26 Research in general populations also reported that optimism is a significant predictor of positive physical health outcomes27 and is associated with healthy development, resilience, aging well, and increased longevity among older adults.12, 13, 28 Consistent with others,16, 17, 29 we found that high social support was significantly associated with higher mean HRQL scores across all domains among women without cancer and some domains (including mental health and social functioning) for women with cancer. However, those domains of HRQL that were susceptible to cancer treatment effects (including physical functioning, general health, vitality, and bodily pain) were not significantly associated with levels of social support after adjustment of survivor's characteristics. This indicates that women with cancer may require targeted social support (e.g., information and service navigation) specific to their disease, treatment, and survivorship challenges for a better HROL across various domains.

There was a wide variation in mean scores across all HRQL domains between the major cancer sites, consistent with previous studies.30 This variation can be attributed to differences in cancer prognosis, patterns of treatment, and the implications for a diagnosis of a particular cancer type and stage at diagnosis for the prospects for survival, suggesting cancer-specific focus is needed in assessing the HRQL among cancer patients. We found that low optimism was significantly associated with lower HRQL across all domains among women with breast cancer or melanoma, adjusting for demographic, behavioral, and other health conditions. However, the association was not statistically significant across all domains (except for mental health) for those with other cancer sites. For example, women with cancer of the digestive organs who had low optimism reported significantly lower HRQL only in mental health. In terms of social support, we observed that lower social support was associated with significantly lower mental health scores among women with breast31 or digestive organ cancer.32 Lower social support was also associated with social functioning scores for women with breast cancer or melanoma but not for other cancer sites.

Optimism and social support were not independent in relation to the association with HRQOL among cancer survivors, particularly for some domains, including physical functioning, social functioning, mental health, and bodily pain. Low optimism was more strongly associated with reduced physical functioning, worse mental health, and greater bodily pain in the presence of lower versus higher social support. On the other hand, the association of low social support with HRQL in the presence of low versus high optimism was mixed, with reduced scores across all domains in the presence of low optimism but increased scores in physical functioning and bodily pain in the presence of high optimism. This mixed association of social support in the presence of low versus high optimism may partly be explained by the fact that optimism, in some situations, may moderate the relation of social support to HRQL outcomes; these two variables can be interdependent and may act as mediators or moderators of the relationship with HRQL among women with cancer.33-35 Moreover, optimism may also affect people's perceptions and ratings of social support.

This study also identified the relationship between a range of sociodemographic, behavioral, and health factors with different HRQL domains. Although increased age at diagnosis was associated with decreased physical functioning, most demographic factors, including area of residence, marital status, and educational qualifications, were not significantly associated with most domains. A recent US-based study reported that marital status and educational attainment are associated with physical health components but not the mental health component of the HRQL.36 Increased time since diagnosis was associated with an increased score in all HRQL domains except for physical functioning. This is consistent with physical functioning scores decreasing with age37 and disability and loss of physical functioning being common in cancer patients.5 Hence, the increased time since diagnosis was not sufficient to offset aging- and cancer-related losses in physical functioning. Consistent with others,8, 36, 38, 39 difficulties in managing available income, having no or low physical activity, and other health conditions were significantly associated with decreased HRQL across all domains among women with cancer and moderate the association of optimism and social support with HRQL domains.

The association of optimism and social support in relation to HRQL has implications for the future design of survivorship care interventions that could identify and focus on areas in which people require support following a cancer diagnosis. However, when designing intervention strategies to enhance optimism and social support among cancer patients, clinical characteristics and other factors that are negatively associated with HRQL, such as difficulties managing available income, low physical activity, and other health conditions, should also be considered. Interventions such as support groups tailored to patient characteristics could provide a platform where patients can share experiences and receive emotional and informational support.40 Additionally, interventions that integrate psychosocial support into routine cancer care, such as patient navigation programs, counseling, and survivorship care planning, may help to improve the psychological and social aspects of survivorship and thereby improve the HRQL.40, 41

Key strengths of this study are the use of in-depth survey data from a large prospective cohort of women and the ascertainment of incident cancers using linked data from the Australian Cancer Database. This design also enabled the inclusion of a non-cancer comparison group. Additionally, we conducted comprehensive statistical analyses, adjusting for time since cancer diagnosis and key sociodemographic characteristics. The use of separate models for each HRQL domain, as well as dedicated models by cancer site, allowed us to understand how optimism and social support were associated with each domain of the HRQL across different cancers.

However, our study has some limitations. First, the SF-36 questionnaire was used to assess HRQL, which is not specifically designed for cancer survivors and may not be sensitive enough to measure cancer and treatment-specific effects on HRQL. However, this tool provides a reliable and valid indication of general health in breast cancer survivors and for generic HRQL.42, 43 Second, we were also unable to exclude reverse causality in the observed relationships. It is possible that women who had better HRQL were more likely to be optimistic and/or to have higher levels of social support rather than the other way around. We could not establish causality due to a lack of prospective data that could be used to address simultaneity bias.44 Larger studies by cancer type with adjusting other clinical information are needed to understand the treatment-related potential differences in HRQL between cancer types and assess the connection between optimism and social support with HRQL domains by cancer type. Finally, those with missing covariate information were likely to have lower HRQL, as many of them could not complete the survey due to frail health conditions or disability.19 However, results from sensitivity analysis reveal an almost similar association between the outcomes and predictor variables when estimating after multiple imputations.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study provides insights into the connection between optimism and social support with HRQL among Australian women following a cancer diagnosis. Higher optimism and social support were significantly associated with better HRQL across various domains, suggesting these psychosocial factors are related to patients’ resilience, ability to cope better with disease and treatment processes, and post-treatment survivorship challenges. Additionally, identifying a range of sociodemographic and health factors associated with different HRQL domains enhances our understanding of the importance of considering these factors to better support women cancer survivors with improved HRQL and overall well-being. While we could not determine the direction of effect from this study, even without causality, the associations observed in our study can help identify people with a higher risk of low HRQL, informing the design and focus areas of potential future survivorship support interventions. Further studies focusing on specific cancer types with prospective data, including clinical characteristics, are warranted for the clinical implications of our findings.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Md Mijanur Rahman, Michael David, Karen Canfell, Julie Byles, and Emily Banks contributed to the study concept and design. Md Mijanur Rahman conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the submitted paper. Md Mijanur Rahman, Michael David, Julia Steinberg.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research on which this article is based was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health by the University of Queensland and the University of Newcastle. We are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for funding and to the women who provided survey data. We are also grateful to the State and Territory Cancer Registries and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) as the custodians of the Australian Cancer Database and assisting in the data linkage process.

Karen Canfell and Emily Banks are supported by the National Health and Research Council of Australia Leadership Investigator Grants (NHMRC; APP1194679 and APP2017742, respectively), and AEC is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (#2008454). Julia Steinberg is supported by a Cancer Institute NSW Fellowship (2022/CDF1154). Karen Canfell is co-PI of an investigator-initiated trial of cervical screening, ‘Compass’, run by the ACPCC, a government-funded not-for-profit charity. Compass receives infrastructure support from the Australian government and the ACPCC has received equipment and a funding contribution from Roche Molecular Diagnostics, USA. Karen Canfell is also co-PI on a major implementation programme Elimination of Cervical Cancer in the Western Pacific which has received support from the Minderoo Foundation and equipment donations from Cepheid Inc.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This data analysis was conducted under conditions approved by the relevant ethics committee(s). As a condition of approval, data are not sharable. Access to data by other individuals or agencies would require appropriate ethical approvals to be in place.