Exploring patient reported quality of life in lung cancer patients: A qualitative study of patient-reported outcome measures

Abstract

Objective

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death globally and provides a major disease burden likely to substantially impact quality of life (QoL). Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been identified as effective methods of evaluating patient QoL. Existing lung cancer–specific PROMs however have uncertain utility and minimal patient involvement in their design and development. This qualitative study aimed to evaluate the patient perspective of existing PROMs and to explore their appropriateness for population-based descriptions of lung cancer–related QoL.

Methods

A descriptive qualitative study was conducted consisting of semi-structured interviews with 14 patients recruited from the Victorian Lung Cancer Registry and Alfred Hospital using purposive sampling. Interviews first explored the factors most important to lung cancer patients QoL, and second, patient's perspectives on the appropriateness of existing PROMs. Thematic analysis was used to develop themes, and content analysis was conducted to determine PROM acceptability.

Results

Five novel themes were identified by patients as being important impacts on QoL: Personal attitude toward the disease is important for coping; independence is valued; relationships with family and friends are important; relationships with treating team are meaningful; personal and public awareness of lung cancer is limited. These patient-identified impacts are poorly covered in existing lung cancer–specific PROMs. Patients welcomed and appreciated the opportunity to complete PROMs; however, they identified problems with existing PROMs relevance, tone, and formatting.

Conclusion

Existing lung cancer PROMs poorly reflect the five themes identified in this study as most important to lung cancer patients QoL. This study reaffirms the need to review existing PROMs to ensure utility and construct validity. Future PROM development must engage key patient-generated themes and evolve to reflect the changing management and therapeutic landscape.

1 INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer globally, plagued by 5-year survival rates of around 20%1 and remains the leading cause of cancer-related death.2, 3 Severe symptoms and treatment side effects contribute to the highest disease burden of any cancer.4 It is therefore critically important to be able to evaluate the determinants and impacts of lung cancer on patient-reported quality of life (QoL).

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) reflects the patient's experience of how health status and medical interventions affect QoL.5 HRQoL can be measured using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) collecting information directly from patients without external interpretation.6

Healthcare increasingly targets patient-centered care, demanding inclusion of the patient voice in healthcare design and monitoring.7-9 Previous studies however demonstrate substantial discrepancy between patient and clinician priorities in healthcare, despite demonstration that increased patient communication and therapeutic collaboration can directly improve key patient outcomes including functional status, treatment adherence, and even mortality.10-16 PROMs provide an essential bridge for this communication gap.

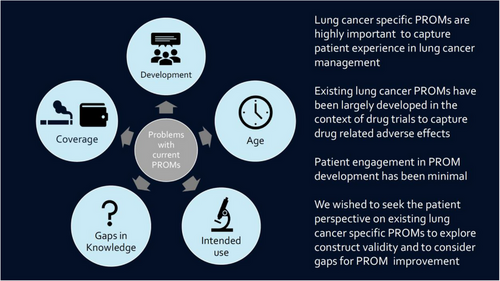

Historically, lung cancer HRQoL PROMs have been developed almost exclusively for use in clinical trials as outcome and toxicity measures for emerging treatments, thereby focused on aspects of health deemed important by researchers, rather than those necessarily prioritized by patients17 (see Figure 1). Patient involvement in the design and development of PROMs however is recognized as key to ensuring effective capture of patient experience by improving tool validity, accessibility, relevance and comprehensibility, and ultimately improving patient uptake.18 Despite these likely benefits and endorsement by bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration, scoping reviews reveal no patient involvement in the development of a quarter of all PROMs.6, 19

The promulgation of patient-centered care demands the evaluation of currently available lung cancer–specific PROMs20-24 to confirm their construct validity and patient perceived utility as measures of HRQoL. This study aimed to explore lung cancer patient experience and to identify outcomes considered important by patients in determining QoL. The specific objectives were to (1) conduct patient interviews to explore factors influencing QoL in lung cancer patients and (2) gain patient perspectives on existing lung cancer PROMs.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted to explore patient perspective of lung cancer HRQoL and perceptions of existing PROMs,25-27 and reported using the COREQ qualitative study criteria reporting guidelines (Table S1).28

2.2 Recruitment

Eligible patients were aged 18 years or over with primary non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Patients were excluded if cognitively impaired or required an interpreter. Purposive sampling was conducted to provide a range of age, gender, management types, and cancer stage.26 Recruitment occurred between March and September 2019, within the chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery outpatient clinics of The Alfred Hospital (Melbourne).29

Participants were provided information about the study, its purpose, type of interview questions, their rights, and researcher independence from the treatment team in order for them to make an informed decision about participation and provide consent.

2.3 Data collection

An interview guide was developed, in consultation with patient consumers, based on a literature review of existing lung cancer PROMs (Table 1), covering demographic information, experience of diagnosis, treatment, symptom burden, and how these factors impacted QoL. Clinical data were captured from the Victorian Lung Cancer Registry (VLCR).29 Finally, a cognitive debriefing activity was performed to evaluate major existing PROMs (European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire [EORTC QLQ-C30] and European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer, 13 questions [EORTC QLQ-LC13] and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung [FACT-L]), where patients were asked to evaluate PROMs in terms of content, tone, and method of administration.

| A. Question guide: quality of life questions | |

|---|---|

| Question wording was designed to loosely guide discussion without being suggestive or limiting relevant content. Probes were designed to encourage more detailed responses to certain questions and their inclusion was based on previous answers. | |

| Question number | Question |

| 1 | Tell me about your experience of being diagnosed with lung cancer. Probe 1: What was helpful? Probe 2: What was unhelpful? |

| 2 | Tell me about your experience of having treatment for your lung cancer. Probe 1: Have you had any side effects of treatment? Probe 2: Have they been managed? Probe 3: How have they affected your quality of life? |

| 3 | Tell me about the symptoms you have experienced as a result of lung cancer? Probe 1: How do they impact you? Probe 2: Which symptoms affect your quality of life the most? |

| 4 | As well as physical symptoms have you experienced an emotional response to having lung cancer? Probe 1: How have others responded to your diagnosis? What has the impact been of that? Probe 1 was included to open up conversation about experienced judgement and stigma. |

| 5 | What other areas of your life have been affected by having lung cancer? Probe 1: Is there anything to do with your disease you feel like you can't talk about with your treating team? Why? Probe 2: For example, relationships, social, spiritual, financial, occupational and leisure. Probe 2 was included to explore themes the consumer representative felt were important and may not be brought up otherwise |

| 6 | On a scale of 1–10, with 1 being the worst quality of life and 10 being the best, where would you rate your current quality of life? Probe 1: What do you consider to be good quality of life? What improves your quality of life? |

| 7 | How would you feel if your treating team asked you about the things we have talked about today? This question was included to explore people's opinion about including a PROM in their care. |

| 8 | What would your advice be to someone newly diagnosed with lung cancer? |

| 9 | How does your current quality of life affect your thoughts and emotions about your future? |

| B. Evaluation of existing tools | |

|---|---|

| Patients were asked to voice their thoughts while filling out the tools. They were then be asked the following questions about the tools. | |

| Question number | Question |

| 1 | What do you think about the length and number of questions? |

| 2 |

What do you think about the content? Probe: Is there anything missing? Is anything unnecessary? |

| 3 | How do you find the wording of the questions? |

| 4 | How do you find the response options and timeframe? |

| 5 |

Where and when would you feel comfortable filling out a form like this? Probe: Would you prefer electronic, telephone or paper form? |

| 6 | Overall opinion, any preference between the two (after completing both). |

- Abbreviation: PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

Patients were asked to complete PROMs via a recorded think-aloud interview where they spoke through their thought processes while completing the PROMs and responses were transcribed for analysis. The interviewer followed up by asking targeted questions about their responses.

2.4 Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Field notes recorded during and after the interview provided contextual details and non-verbal cues. Data were managed with the program NVivo (QSR International 2018). A coding guide was developed deductively based on the information from the literature review, existing PROMs, and the interview guide.

A coding guide was developed deductively based on the information from the literature review, existing PROMs, and the interview guide. These codes were applied deductively to the transcripts. Inductive coding was used to identify concepts from the data. To generate initial inductive codes, perspective, processes, encounters, relationships, meaning, and feeling about the diagnosis experience and the impact of lung cancer on QoL were coded.33, 34 The inductive and deductive codes were reviewed to identify themes. The themes were then defined and named and refined through discussion with all authors and iterative cycles of going back and forth between the transcripts, codes, and themes.33, 34 Coding integrity was checked by cross-coding by an independent researcher not involved in the project of >10% of interviews. EJ-M led the coding under the supervision of DA regularly checking coding processes and interpretations. RGS and JZ were involved in discussions of theme development and naming. RGS also read all transcripts to ensure familiarity with the data.

Think-aloud interviews were analyzed using content analysis, specifically categorizing content, tone, and administration.

2.5 Researcher positionality statements

EJ-M is a female fourth-year medical student completing her honors year under the supervision of DA and RGS. DA is a female health services and qualitative researcher with lived experience of four chronic health conditions (non-cancer). RGS is a male respiratory physician and the clinical lead of the Victorian Lung Cancer Registry. JZ is a male medical oncologist, academic lead of the Victorian Lung Cancer Registry, head of the cancer research program at the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine and the inaugural Tony Charlton Chair in Cancer Research at Alfred Health. RGS, DA, and JZ have an interest in PROMs, QoL, and quality of care.

2.6 Ethics

Ethics approval was given by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Alfred Health and Monash University (277/18).

3 RESULTS

Fourteen patients with NSCLC were interviewed with median age 69 (45–83) years and equal male and female representation (Table 2, with brief patient disease characteristics provided in Table S2). Time since diagnosis ranged from 1 week to more than 2 years. Patients had a range of smoking history, treatment types, and were of varied socioeconomic and insurance status. Interviews were conducted either face to face10 or by phone4 with median interview length of 35 min (range 28–130 min).

| Patients (n = 14) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 7 (50%) |

| Female | 7 (50%) |

| Age | |

| 60 | 4 (29%) |

| 61–70 | 5 (36%) |

| 71–80 | 4 (29%) |

| >80 | 1 (7%) |

| Living arrangements | |

| Alone | 4 (29%) |

| With family | 10 (71%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| High school or less | 9 (64%) |

| University or higher | 5 (36%) |

| Country born | |

| Australia | 9 (64%) |

| Overseas | 5 (36%) |

| Living | |

| Regional/rural | 3 (21%) |

| Melbourne | 11 (79%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 1 (7%) |

| Former | 9 (64%) |

| Current | 4 (29%) |

| When diagnosed | |

| <8 weeks | 3 (21%) |

| 8 weeks–6 months | 2 (14%) |

| 6 months to 2 years | 7 (50%) |

| >2 years | 2 (14%) |

| Stage | |

| I | 1 (7%) |

| II | 1 (7%) |

| III | 1 (7%) |

| IV | 11 (79%) |

| Treatmenta | |

| Chemotherapy | 7 (50%) |

| Radiotherapy | 5 (36%) |

| Surgery | 3 (21%) |

| Immunotherapy | 8 (57%) |

| ECOG status | |

| 0 | 2 (14%) |

| 1 | 8 (57%) |

| 2 | 4 (29%) |

| 3 | 0 (0%) |

| 4 | 0 (0%) |

- Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

- a Treatment percentages >100% total as most patients have more than one treatment type.

3.1 Patient identified QoL impacts

The following five themes were identified as important factors contributing to QoL in Victorian lung cancer patients (Table 3):

| Themes | Subthemes | Demonstrative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Personal attitude toward the disease is important for coping | Acceptance | “I go by the philosophy…accept the things you can't change…and change the things you can…well I can't change this, so I accept it.” (T11) |

| Dealing with uncertainty | “I might live another 20 years on this treatment or it might come back tomorrow, it's just really hard, so I kind of like, like I don't worry about things until they happen.” (T8) | |

| Coming to terms with mortality | “They told me I'm terminal…I guess you have to sort of come to terms with that, because you've got to live with it every day.” (T8) | |

| Positivity | “At the beginning, this nurse, he said to me, ‘have hope until they tell you otherwise,’ and I thought that was quite useful…so yeah just trying to stay positive and appreciate every day.” (T5) | |

| Determination to maintain health |

“I push myself, I never stay in bed.” (T2) “They said you're going to get very sick, you might get very sick to the point that you're going to lose so much weight that we're going to have to put you in hospital, put you on a drip…there's just little things that can make you feel better by being in control and I thought well I'm not going to end up on a drip, I'll keep eating.” (T5) |

|

| Being informed | “Early on I read ferociously…I couldn't get enough information.” (T3) | |

| Awareness about lung cancer is significant | Lack of individual awareness |

“I probably am still suffering from shock…even after all these months I can't believe that.” (T6) “There were no symptoms for lung cancer, no coughing…you know people cough up blood and stuff like that, I haven't had any of that.” (D2) |

| Lack of public awareness |

“I kind of missed the signs because there was never any mention of it so I didn't know what I was sort of looking for.” (T5) “It's almost like a dirty cancer; people don't want to talk about it.” (T8) |

|

| Guilt and blame |

“I don't blame the doctors, I don't blame anybody, I blame myself.” (T2) “It's such a taboo thing now and yet, my generation was sold it… I'm not going to disown my responsibility, it was my decision to smoke, but I'm not sure it really was a decision.” (D1) |

|

| Stigma |

“There's a terrible stigma with lung cancer…the first thing people ask you is ‘are you a smoker’ and that's truly insulting…it's almost like, oh well you smoked you deserve it! Does that mean you'd say to someone, ‘oh you got skin melanoma, did you stay out in the sun a lot, oh you deserve the cancer’…nobody deserves to get cancer, no matter what.” (T8) “They don't want to admit it but they keep on pointing the finger at me, telling me it's all self-inflicted.” (T9) |

|

| Relationships with family and friends are important | Support |

“The family, they're real good, very supportive.” (T1) “I've been overwhelmed by the kindness of people, genuine kindness.” (T3) |

| Strain | “My daughter that's looking after me, I want to go one way, she wants to go the other.” (D3) | |

| Concern for others | “Most people that are going to pass on know they are, and they can live with it, it's the ones left behind that can't live with it.” (D3) | |

| Responsibilities | “The worst thing is worrying about my kids and worrying if anything does happen that they're going to be ok.” (T8) | |

| Disclosure of diagnosis |

“I wanted people to know, not find out from someone else.” (D2) “I think if they knew…it's literally signing their death warrants.” (T7) “I did tell one very close friend and he said ‘oh, you'll be dead in a year.” (T1) |

|

| Relationships with treating team are meaningful | Trust | “It makes a difference to have a good treating team that you can trust, you need to be able to trust your doctors.” (T8) |

| Support | “I've found that the team has been really supportive.” (T8) | |

| Communication skills |

“The nursing staff are incredibly helpful…they include you in the process…they make sure you're informed, and that gives you confidence.” (T3) “I found explaining things in layman's terms very helpful so I understood what was going on.” (T5) |

|

| Miscommunication |

“Yeah well the radiographer was just about to tell me that I was cancer free and I told him, oh you obviously haven't seen my latest scan and then he was embarrassed, so, because the surgeons hadn't told him.” (T10) “A registrar came in and she sort of had a big smile on her face and she sort of said, ‘oh and you've got lung cancer,’ and I was like ‘what?’… it was two in the morning…I probably would have liked it broken to me a bit better than it was…I had no idea that it was cancer and so serious.” (T8) “I had a lot of different oncologists at the start… then I started interpreting that ‘oh because this [is].. a terminal case, its stage 4 lung cancer, you're pretty well stuffed so it doesn't matter which oncologist.” (T7) |

|

| Independence is valued | Mobility and fitness |

“I love getting out and going for a short walk often…I don't even mind if I rug up on a really cold winter day and go out for a walk, it's so good.” (T3) “I totally believe that independence, physical and mental independence is the most important thing.” (T4) |

| Caring for self | “I certainly don't want to become just lying in bed, waiting to die unless I can do things for myself.” (T6) | |

| Autonomy | “I'm able to manage my life independently up until now and I intend to keep doing so for as long as I can… I can't envisage myself not being responsible for myself.” (T3) | |

| Not being a burden | “I'd like the choice, ‘no, I'll go now thanks’… rather than be a burden on anybody.” (T11) |

- Note: Patient quotes elicited in either “diagnosis phase” (D) or “treatment phase” (T) with patient registration number.

3.1.1 Personal attitude toward the disease is important for coping

The most prominent and consistent theme throughout the interviews was how the patient's mindset and attitude toward their disease helped with their coping. For the majority of patients, acceptance of their disease was critical for their psychological well-being, and helped deal with symptom burden and intensive treatment demands as well as managing the uncertainty of their prognosis. For those with a terminal diagnosis, it helped in coming to terms with their mortality. Acceptance did not mean that these patients were devoid of hope, and maintaining a positive mindset was a dominant subtheme. Patients also often embraced a proactive and determined attitude to contribute to their overall health and therefore increased feeling of “control” about the disease management and trajectory. Similarly, the majority of patients educated themselves about lung cancer, finding knowledge “empowering,” and making the experience “not as frightening.”

3.1.2 Independence is valued

Independence was perceived by patients as one of the “most important” elements in QoL and most threatened by the diagnosis of lung cancer. Preservation of mobility, fitness, and exercise capacity was identified as critical to independence and improved mood. Independence, self-care and maintaining autonomy were highly valued and patients often used their mobility and ability for self-care as markers of disease progression and loss of QoL. Patients expressed lack of autonomy with third-person passivity including they sent me and they took me back. By contrast, end of life preparation could return a sense of control over their disease management by reassuring patients that they would maintain autonomy even once they had lost their independence. While maintaining independence had primary importance, it was equally important that patients not become a burden to other people.

3.1.3 Relationships with family and friends are important

The majority of patients identified relationships with family and friends as important, and conversely, the absence of a strong support network as detrimental. Most experienced that when diagnosed people rallied around them for which they were appreciative of support which positively impacted coping and experience of living with lung cancer. However, patients identified that such a serious diagnosis could also put a strain on relationships. Even more significantly, patients expressed concern for how family and friends were coping with the diagnosis. Surprisingly, this was often described as more distressing for patients than their health. Patients responsible for the care and welfare of others described this as an additional concern.

Disclosure of diagnosis was an important subtheme. Patients reported careful consideration of both the timing of disclosure and to whom the diagnosis needed to be disclosed. Patients described competing needs for support, a wish to avoid burdening others and also a fear of adverse judgment.

3.1.4 Relationships with treating team are meaningful

Patients emphasized importance of the relationship with their treating team impacting experience of living with lung cancer and overall QoL with trust in the treating team linked strongly with how patients perceived their disease management. In general, patients were willing to engage with their treating team and very happy to talk to them about anything. Patients appreciated the conversation about more than just physical symptoms, but also emotional coping, suggesting deeper compassion. Being supportive, sympathetic, and respectful were qualities identified as important in a treating team.

Similarly, allowing the patient to be an active participant in their care by include[ing] [them] in the process improved team–patient relationships. Communication skills, both good and bad, had profound effects on a patient's experience. Miscommunication, poor explanations, and appearing too rushed often led patients to believe their doctors lacked respect for them, especially around the highly stressful time of diagnosis. Multiple patients expressed disappointment when recalling how their diagnosis was delivered and a perceived lack of sensitivity from their doctors.

3.1.5 Limited personal and public awareness of lung cancer

A lack of individual awareness about lung cancer emerged with patients describing their diagnosis as a distressing shock. Many patients described a strange absence of symptoms before diagnosis, discrepant from their perceptions of disease severity. Patients described frequent misdiagnosis of symptoms as non-sinister in origin, for example, getting old or a cold highlighting the variety and lack of specificity in symptom presentation.

Patients perceived a lack of public awareness and stigma leading to experiences of guilt and blame about their smoking, with one patient revealing that their diagnosing doctor described their cancer as bigger than [a] pack of cigarettes.

In addition to the five themes patients identified above, patients were asked to rate their current overall QoL on a scale of 1–10. The average rating was 7.2/10, and patients were generally happy with the quality of life they had.

3.2 Patient acceptability of available PROMs

Overall, patients reported being happy to complete PROMs identifying a valuable opportunity to raise awareness about the experience of having lung cancer and to help out other people.

Content: Overall, patients reported the PROMs content as similar, however a preference was expressed for the FACT-L described as more emotional. It was expressed that the oncologist would know a lot of these physical type answers already; however, the psychosocial questions were less thoroughly covered. Patients believed that longer PROMs were necessary to get an overall picture and wouldn't take… too long to fill out. While some patients reported the questions were all relevant, with others reporting virtually none relevant. PROM relevance varied, for some it was too treatment specific, especially for those questioned in the diagnosis phase. For some with few symptoms, the symptom lists suggested a daunting list of symptoms they might have coming. Patients with advanced disease reported preferring questions on coping and meaning. Patients having immunotherapies found conventional chemotherapy side effect questions less relevant.

Tone: Patients expressed a desire for a more positive tone finding the FACT-L's use of statements very negative and dogmatic, while by comparison the use of questions were “more neutral” and allowed them to “formulate [their] own answer”.

Administration: Pen and paper was the most acceptable method of administration, and only a few patients said they would find electronic modalities acceptable reflecting the older demographic. The majority thought completion either while they're waiting for their treatment, or while having treatment in the case of chemotherapy and immunotherapy and were happy to complete it in a public space or at home.

4 DISCUSSION

This qualitative descriptive study identified five important determinants of HRQoL in lung cancer patients that are largely underrepresented in existing PROMs.

Patients identified acceptance and positivity to the diagnosis as contributing to QoL supporting previous reports that attitude toward disease are important for both coping with lung cancer and managing key personal challenges including coping with symptoms, uncertainty, experience of hope, networks and independence, thoughts of death, guilt, shame, sadness, and anger.17, 30-33 Other lung cancer patients have similarly reported that involvement in disease management and optimization of their health could increase their sense of control in a time of much uncertainty.17, 30, 32

The desire to maintain independence, autonomy, and mobility and therefore not become a burden on others is strongly supported by existing literature.30, 32, 34-36

Our patients confirmed the importance of support from family and friends reported widely in qualitative studies on lung cancer patient QoL.17, 32-35, 37-39 Studies have found the same contrast in how the diagnosis of lung cancer could lead to increased support but also strain some relationships.30, 33 The strong feeling of concern for others well-being experienced by many patients in our study was also identified in other similar studies of lung cancer patients.33

Patients reported comfort and confidence when the relationship with the treating team was identified as supportive and trusting and a key element derived from continuity of care through the disease pathway.32-34, 40 The profound impact of communication on patient trust has been identified with patients appreciating clear, consistent, and personalized communication, ideally provided by the treating physician, especially during diagnosis and potentially stressful changes in treatment.30, 32, 33, 41

Patients additionally identified an eagerness to be involved in their care and decision making, which is congruent with existing literature.40 Factors suggested to enhance patient-centered communication include balanced information exchange between doctor and patient, the sharing of power and responsibility in decision making, the development of therapeutic alliance based on patient desire, and the recognition of both patient and physician as person. These findings draw in the broader discourse in medicine of increasing patient participation as a likely contributor to improved QoL.16, 42, 43

Patients identified the major impact of shock of diagnosis in which a discrepancy between personal awareness, symptom burden, and the severity of the prognosis was associated with new diagnosis.17, 33, 41 Patients noted that this personal shock was delivered within a milieu of stigma and negative illness appraisals with 30% of lung cancer patients blaming themselves for their disease,44, 45 with Chambers et al. finding 49% of patients were significantly anxious, 41% were depressed, and 51% were distressed.46 Such stigma has been demonstrated to delay help-seeking, increase non-disclosure of diagnosis, and contribute to poorer adjustment, constraint of interpersonal discussions, and heightens feelings of threat, contributing to poorer psychosocial and health outcomes.32, 33, 46, 47

Importantly absent from the five themes identified in our study were the impacts of symptoms and side effects often identified in quantitative literature as the major contributor to burden of disease in lung cancer.4 Our question guide was based on existing literature and PROMs including an emphasis on lung cancer symptoms and treatment side effects, therefore expected to emerge as significant themes. Patients however instead reported symptoms only indirectly altered QoL by limiting or influencing the five main themes identified, accepting symptoms and treatment side effects as “part of lung cancer” in general reporting them as transient or well managed. Consistently, a 2017 qualitative study into the coping and well-being of lung cancer patients also identified patients having a higher threshold for symptom and treatment side effects than expected.17 Further, qualitative research identifies important psychosocial stressors independent of treatment type, having significant adverse impacts on HRQoL, including influences on families, family system impacts, and social environmental responses as key determinants of HRQoL, which remain largely undetected by currently available PROMs.48

Overall, interviewed patients had significant concerns around the relevance of the major PROMs to their point in the disease trajectory since diagnosis. Additionally, patients expressed concern regarding PROM design, presentation, and content, suggesting changes to question wording, response options, and the use of subheadings. Patients believed that longer PROMs were required to ensure that they measured the outcomes important to them. This highlights that a longer length of tool may still be acceptable if the questions are meaningful and promote engagement with clinical care. Guidance from the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care emphasizes the importance of developing PROMs in consultation with patients and indicate that the time required to complete a PROM should be no longer that 15 minutes https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/selecting-proms.

Existing lung cancer PROMs had little or no engagement of the five patient-identified themes reported as important to QoL (Table 4). While many asked about specific emotions, they were mainly negative, for example, “did you feel depressed?”. Few asked about attitude or positive coping mechanisms and our patients suggested the PROMs would benefit from a more positive tone. While some tools covered functional status well, none asked about independence, autonomy, and sense of burden to others. The two PROMs were mainly designed as symptom assessment tools; the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale (LCSS) and M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory-Lung Cancer (MDASI-LC) were especially poor in their coverage of these themes. Critically, none of the PROMs included any reference to the patients’ relationship with their treating team despite this being so significant to patients themselves. The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of PROM measures used in the measurement of health-related outcomes is of critical importance and may be further enhanced by appropriate evaluation using the COSMIN checklist.49

| Personal attitude toward the disease is important for coping | Lack of awareness about lung cancer | Relationships with family and friends are important | Relationships with treating team are meaningful | Independence is valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | — | — | 2 (general) | — | 1 (self-care activities) |

| EORTC QLQ-LC13 | — | — | — | — | — |

| EORTC QLQ-LC29 | — | — | — | — | — |

| FACT-L | 3 (general coping, acceptance, maintaining normality) | 1 (smoking regret) |

1 (responsibility) + 6 (support) |

— | — |

| LCSS | — | — | — | — | — |

| MDASI-LC | — | — | 1 (relationships) | — | — |

- Note: Number indicates number of included questions relevant to theme.

- Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; EORTC QLQ-LC13, European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer, 13 questions; EORTC QLQ-LC29, European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer, 29 questions; FACT-L, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung; LCSS, Lung Cancer Symptom Scale; MDASI-LC, M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory-Lung Cancer.

4.1 Strengths

This study engaged a rigorous interview-based qualitative research methodology. Numerous techniques were used to enhance trustworthiness, as per Lincoln and Guba's criteria, including consumer representation, researcher and data triangulation, the use of medical records for confirmation, and >10% of interviews being cross-coded.50

4.2 Limitations

Our study was restricted to NSCLC and largely to advanced stage disease and while the majority of Victorian patients are diagnosed in stage IV, it is important to explore potential differential in impacts in early stage disease.51 Patients agreeing to participate in an interview-based study may have different perspectives on QoL and PROM value compared to nonparticipants and this may invite selection bias. We attempted to reduce this impact by making the interviews as flexible and convenient for patients as possible to increase the range of patients recruited. Further, there is wide heterogeneity in NSCLC patient characteristics, treatment types, and treatment combinations. As an example, our study was conducted prior to universal government-funded access to immunotherapies and targeted therapies, and the study of these measures in emerging treatment populations will be highly important given the possibility of different treatment experiences on these agents. This diversity may limit generalizability to specific patient and treatment cohorts. The rapid evolution of NSCLC diagnostics and therapeutics provides an important opportunity to confirm the utility of lung cancer PROMs in diverse patient cohorts.

The European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Lung Cancer, 29 questions (EORTC QLQ-LC29) is a lung cancer–specific HRQoL measure published after the commencement of this study and was not available for evaluation in this study. Containing 29 questions, 26 were related to disease and treatment-related symptoms and three were related to worry about future health, fear of disease progression, and decrease in physical capability but importantly no questions in relation to the five important HRQoL determinants identified within our study.

An important opportunity exists to map existing HRQoL instruments in lung cancer to broader HRQoL and PROM conceptual frameworks52, 53 considering the core domains of biological and physiological factors, symptom status, functional status, general health perceptions, and perceived QOL to explore opportunities for further inclusion or enhancement of relevant individual, structure and process elements of disease, patient, and treatment-related factors.54

5 CONCLUSION

This study identifies five patient-identified themes that were deemed important determinants of QoL and were substantially under-represented within existing PROMs. Patients expressed concern regarding PROM relevance, noting that generic PROM tools may not be appropriate for patients with different stages, different phases of the disease pathway, and undergoing diverse treatments with distinct adverse event profiles. Patients supported the use of PROMs and identified this as a means for engaging participation in care and improving clinician–patient communication. Further research is needed to improve relevance and effectiveness of PROMs to enhance patient-centered lung cancer management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study. We gratefully acknowledge Claire Zammit, Margaret Brand, and the Victorian Lung Cancer Registry for assistance in patient recruitment and patient description. We also thank the VLCR consumer advisor for their feedback on the interview guide and Irushi Ratnayake for cross-coding the data.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.