The pathophysiology and current treatments for the subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma: An updated review

Abstract

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is a rare cutaneous T cell lymphoma, which is indolent in nature but could claim life if not correctly diagnosed and promptly treated. SPTCL is usually presented clinically as painless subcutaneous and erythematous nodules over the trunk or extremities. Active clinical vigilance for these subcutaneous nodules or panniculitis-like lesions is warranted. A biopsy must be performed in order to make a correct diagnosis. Positron emission tomography scan is utilized for disease staging and treatment follow-up. Due to the rarity of this lymphoma, a standard treatment protocol is not established yet. However, most cases of SPTCL could be treated well under immunosuppressive or polychemotherapeutic drugs except in cases with hemophagocytic syndrome. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be used in refractory or relapse cases. In this review, we presented a case of SPTCL with long-term complete remission. Meanwhile, since most clinical evidences and experiences of SPTCL are based mostly on case reports or small case series, and the understanding of the SPTCL pathophysiology is limited, we reviewed and updated the pathophysiology and treatments of SPTCL.

1 INTRODUCTION

As one of the most important lymphoid organs to defend exogenous pathogens, the skin, similar to the gastrointestinal system, is prone to develop extranodal lymphomas. In classical nodal lymphomas, B cell lineage lymphomas (such as follicular lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma) are more common than T cell lineage lymphomas (such as anaplastic large cell lymphoma). However, in extranodal cutaneous lymphomas, T cell lineage lymphomas outnumber B cell lymphomas. The most common cutaneous lymphoma subtype is mycosis fungoides (MF), a T cell lymphoma, which is characterized by its indolent disease course but may evolve from patch stage, plaque stage, to leukemia stage, namely, Sezary syndrome. We previously reviewed the non-MF cutaneous lymphomas in one major referral center.1 Non-MF primary cutaneous lymphomas include extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, peripheral T cell lymphoma (not otherwise specified), cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, adult T cell lymphoma, and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma (SPTCL). Disease features, treatment methods, and prognosis vary substantially among these different lymphomas. SPTCL is worth knowing because it manifests itself as several subcutaneous indurations and could be masqueraded as other nonmalignant panniculitis. First described by Gonzales et al. in 1991, SPTCL is typically involved in subcutaneous fat.2 In the WHO-EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas in 2005, SPTCL is defined as CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma expressing αβ T-cell receptors (TCRs) and CD4−, CD8+, and CD56− phenotypes, which is limited to subcutaneous fat and has a usually indolent clinical course (SPTL-AB).3 On the other hand, cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (CGD-TCL), previously called SPTL-GD, carries a distinctive phenotype (CD4−, CD8−, CD56+) and poor prognosis.4 Due to obvious phenotypic and prognostic differences between these two diseases, the term SPTCL refers only to SPTL-AB, while SPTL-GD should not be applied. SPTLC is uncommon among non-Hodgkin lymphomas.5 The prevalence of SPTLC in Japan from 2007 to 2011 was 2.3% among all the cutaneous lymphomas.6 Median age at presentation of SPTCL is 35 years, which seems to be younger than other cutaneous lymphomas.7 About 20% of SPTCL are associated with autoimmune diseases.8 Of note, 15%–20% of cases are complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS),5 which is often lethal and is characterized by uncontrolled systemic inflammation, hypercytokinemia, and multiple organ failure.9

In this article, we first presented a case of SPTCL to report the clinical manifestations and treatment courses. More importantly, due to the rarity of this disease, limited clinical experiences, and paucity of pathophysiological reviews, we reviewed the histopathology, pathophysiology, and clinical management of SPTCL from previous literature.

2 CASE PRESENTATION

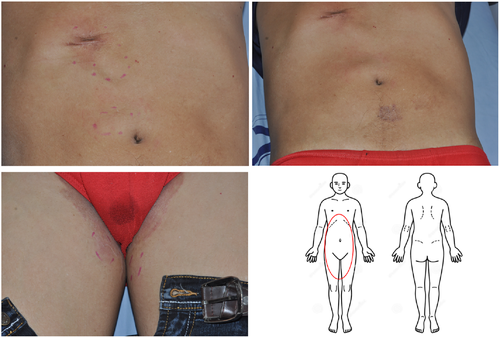

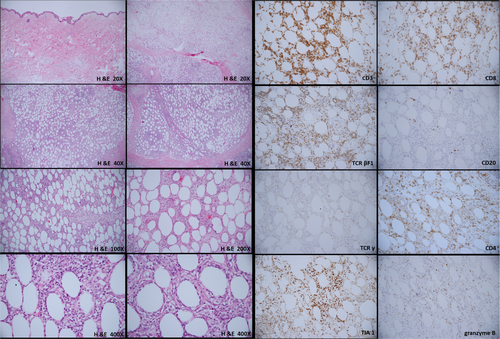

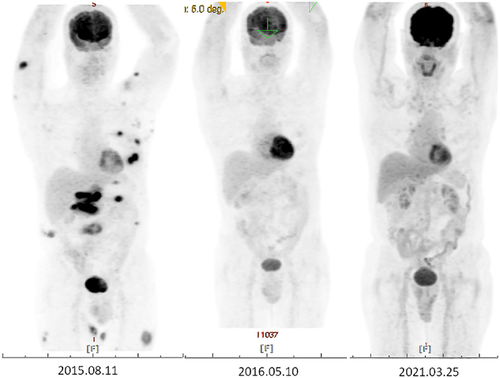

A 67-year-old man, with hypertension and benign prostatic hyperplasia, developed multiple erythematous, mild itching, but painless subcutaneous nodules over the abdominal area and groin for 3 months. He did not pay much attention to these lesions in the beginning. However, the nodule enlarged progressively, especially in bilateral thighs. The patient visited our outpatient department for help. He denied any systemic symptoms, including fever, weight loss, or other B symptoms. Physical examination showed several erythematous, well-defined plaques and nodules over the abdomen and inguinal area with some surface lichenification (Figure 1). Excisional biopsy of one of the abdominal lesions was performed and the pathology report showed subtle rimming of the atypical lymphocytes surrounding individual fat cells, admixed with foamy histiocytes and fat necrosis without the involvement of the overlying epidermis and dermis. These atypical lymphocytes show the immunophenotype of CD3(+), CD20(–), CD4(–/+), CD8(+), TIA1(+/–), granzyme B (+/–), TCR βF1(+), TCRγ(–), and CD56(–) (Figure 2). Based on these clinical and pathological findings, a diagnosis of SPTCL was rendered. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan, a procedure to detect metabolically active malignant lesions, showed extensive involvement of subcutaneous fat in the trunk and extremities, as well as plausible bilateral axillary lymph nodes involvement (Figure 3). Per stage IV of SPTCL, chemotherapy was initiated by ProMACE-CytaBOM (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, cytozar, bleomycin, vincristine, methotrexate, and prednisone)10 for three consecutive courses until October 2015, with incomplete remission. Subsequently, chemotherapy with ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone [solu-medrol], high-dose cytarabine [ara-C], and cisplatin)11 for two courses was administered because of incomplete remission of initial lesions. Unfortunately, residual tumors remained after these five courses of chemotherapy with two different regimens; auto-peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT) was performed in March 2016. The patient was successfully discharged 3 weeks later. Two months after the auto-PBSCT, the follow-up FDG-PET scan image showed metabolic complete remission of lymphoma. There is a long-term remission after auto-PBSCT. The follow-up FDG-PET scan in March 2021 showed no definite evidence of the lymphoma relapse. In summary, this 67-year-old patient received polychemotherapy with partial remission and then received auto-PBSCT, with durable long-term remission.

Below, we review histopathology, pathophysiology, and clinical management of SPTCL.

2.1 Clinical characteristics

Clinically, SPTCL is usually present with multiple subcutaneous, erythematous, painless plaques, or nodules over extremities.8 Ulceration is uncommon, compared to primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma. Systemic symptoms may include fever, night sweats, weight loss, pancytopenia, and myalgias, and lab exams may show abnormal liver function tests. In one Japanese study, they reviewed 22 cases based on summarizing previous case reports. They demonstrated that B symptoms (fever, night sweats, and weight loss) were more common in Japanese cases than those in European cases. However, the associations with autoimmune diseases in Japanese cases are lower than those in European cases.12 Lymph nodes and bone marrow are usually spared,8, 13 but the disease may progress and involve lymph nodes and bone marrow in advanced stages.

HPS is a life-threatening disease, characterized by prolonged fever, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, and hemophagocytosis by activated, morphologically benign macrophages.14 Biochemical profiles include high levels of triglycerides, ferritin, transaminases, bilirubin, and Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and a low level of fibrinogen.15, 16 This syndrome could be divided into genetic form (primary) or acquired form (secondary). Acquired form HPS could be divided into three categories: infection-associated, Epstein-Barr virus-associated, and malignancy-associated. Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (LAHS) is one of the malignancy-associated HPS.17, 18 The most common type of LAHS is T/natural killer (NK)-cell lymphoma.19 In a single-center retrospective study in China, 57 patients were diagnosed with LAHS, including 43 cases of T/NK cell lymphoma and 14 cases of B cell lymphoma. Among the 43 cases of T/NK cell lymphoma, most cases were extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (26 cases), and two cases were SPTCL.20 Based on one European statistical data, 15%–20% of SPTCL are complicated by HPS.5

2.2 Histopathology

The typical histological pattern of SPTCL is lobular panniculitis with spared interlobular septum, epidermis, and dermis. Dense atypical lymphocytes infiltrate adipose tissue. Hyperchromatism and irregular nuclear membranes (cerebriform-like nuclei) are noted in these atypical cells. Some cases show mucin deposition, plasma cell aggregates, vacuolar interface changes, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and periadnexal lymphocytes.21, 22 In immunohistochemistry, these neoplastic T-cells express CD8, βF1, and other cytotoxic T-cell markers including granzyme B, perforin, and TIA1. A high Ki-67 proliferation index is also recorded.6

Histologically, it is difficult to distinguish SPTCL from lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP). These two diseases share many similar histopathological features. Most of the time, LEP presents epidermal and dermal changes of LE, intradermal mucin deposition, lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers, infiltration of plasma cells, and aggregation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. No presence of atypical T cells and low Ki-67 proliferation index are two reliable histopathological features of LEP to distinguish these two diseases.21 The expression of MYC, an oncoprotein as a transcription factor, was higher in SPTCL than that in lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP).23 This marker could be used for differential diagnosis as well. It is noteworthy that CD8+, βF1+, granzyme B+, and monoclonal T-cell clone, which are typical features in SPTCL, could also be expressed in LEP.22, 24, 25

Microscopically, HPS is featured with a prominent and diffuse accumulation of lymphocytes and macrophages occasionally displaying hemophagocytosis. These findings are classically seen in the bone marrow but could be also in the spleen, lymph nodes, liver, skin, lungs, meninges, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and subcutaneous tissue.26-28 The diagnosis of HPS is very important. Aggressive treatments would be critical in SPTCL with HPS. Moreover, SPTCL with HPS shows a poorer prognosis than SPTCL without HPS. In one retrospective study, the 5-year overall survival rate of SPTCL with HPS declined to half, compared to SPTCL without HPS.4

2.3 Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of SPTCL remains largely unknown. A genetic study showed that biallelic HAVCR2 (TIM-3) germline mutations frequently exist in sporadic SPTCL.29 TIM-3, as a negative immune checkpoint, modulates the function of T lymphocytes.30 Intracellular signaling analysis study showed an obvious involvement in phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and JAK–STAT signaling pathways in 18 SPTCL cases in China.32 One study revealed the expression of CCR5 on neoplastic T-cell and ligands for CCR5 (CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5) located on the adipocyte membrane.13

The pathophysiology of malignancy-associated HPS remains elusive. The possible mechanisms could include aberrant cytotoxic pathway by the neoplasm through neoplastic cytotoxic cell itself or through malignancy-associated immune dysregulation.18 EBV infection could be a possible etiology of SPTCL with HPS, although usually lacking in sporadic SPTCL.32 The expression of SAP/SH2D1A gene is inhibited by EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), contributing to an increased cytokine secretion.33, 34 This mechanism is similar to the pathophysiology of the genetic form of HPS. In addition, the apoptosis of EBV-infected T cells is postponed through TNF-α/TNF receptor 1 via the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signal pathway.35

2.4 Management

So far, there is still no standardized treatment for SPTCL. The aims of treatment are (1) interrupting the proliferation of atypical T cells, (2) preventing cytokines from over-releasing, and (3) balancing the immune environment. Medical treatment could be roughly divided into immunosuppressive drug-based (corticosteroids alone or in combination with cyclosporine A or methotrexate) regimen or chemotherapeutic drug-based (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [CHOP] or CHOP-like) regimen (Table 1).12, 13, 36 Glucocorticoids, as an immunosuppressive drug, bind to glucocorticoid receptor in the cytoplasm. Activated glucocorticoid receptor binds to DNA, interrupting other transcription factors binding. As a result, the gene could not be transcribed.37 Another mechanism is that glucocorticoid recruits histone deacetylase to “close the chromatin structure” where NF-κB needs to bind.38 Glucocorticoids inhibit genes that code for the cytokines IL-1, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ. IL-2 plays the most important role in T cell proliferation.39 Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis through Bcl-2 is another mechanism.40

| Immunosppressive drug-based |

|---|

| SPTCL without HPS |

| Chemotherapeutic drug-based |

|---|

|

| Others |

|---|

|

|

Chemotherapy, including cytotoxic or antimetabolic agents to inhibit or interrupt the cell cycle, is commonly utilized in treating solid cancers and lymphomas. In one clinical report of 27 patients in France, they demonstrated that immunosuppressive drugs generate better treatment response in SPTCL than polychemotherapy does, with a complete remission rate of 81.2% and 28.5%, respectively.41 However, in another retrospective study of 70 patients also in France, there was no difference in complete remission rate between these two groups.42

Bexarotene, a retinoid, succeeded in treating SPTCL in combination with prednisolone in one case report in Germany.43 Bexarotene, selectively activating retinoid-X receptors, has a dual mechanism of action in cutaneous T cell lymphoma, by inhibiting the proliferation of T cells and inducing apoptosis through the p53/p73-dependent cell cycle inhibition pathway.44, 45 Recombinant human interferon α-1b (IFNα-1b) may have a role in the treatment of SPTCL,46 based on previous experience in the treatment of MF and Sezary syndrome. INF-α stimulates NK cells and CD8+ T cells and inhibits Th2 cytokines from malignant lymphoma cells, facilitating the recovery of Th1/Th2 imbalance.47 Besides, INF suppresses tumor cells by prolonging the tumor cell cycle, inhibiting oncogenes, and promoting the expression of tumor suppressor genes and antiproliferation genes.48, 49 Radiation treatment could be utilized in localized lesions in selective cases.50

Stem cell transplantation (SCT) can be performed in refractory or disseminated cases (Table 2).5, 13 SCT is a procedure in which a patient receives healthy stem cells to replace damaged stem cells. Most of the time, high doses of chemotherapy are given before SCT, namely, the conditioning treatment. Healthy stem cells, from autologous or allogenic source, are infused into the patient's bloodstream via central venous catheter. These stem cells travel to the bone marrow and form new healthy hemolymphatic cells. Clinically, SCT is a fully experienced method to cure leukemia or lymphoma. Taking our case for instance, the patient, suffering from a refractory SPTCL, has long-term remission after receiving auto-peripheral blood SCT.

| Initial treatment (immunosuppressive or chemotherapeutic drugs) failed, then followed by |

|---|

| Refractory or relapsed SPTCL |

|

Cyclosporine A showed an excellent response in relapsed and refractory SPTCL.51 Interestingly, in a case report in Korea, cyclosporine A was used for the first-line therapy that induced a long-term remission.52 Cyclosporine A reduces T-cell function by inhibiting calcineurin in the calcineurin–phosphatase pathway. Calcineurin dephosphorylates the transcription factor NF-AT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells), increasing the transcription of genes for IL-2 and related cytokines (IL-3, IL-4, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)).53

Chidamide, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, may play a role in refractory SPTCL case, proposed in a case report in China.54 Histone deacetylase inhibitors could modulate gene expression via hyperacetylation of histones and change nonhistone proteins via regulation at the epigenetic and posttranslational modification levels.55 Another kind of histone deacetylase inhibitor, Romidepsin, was also utilized in the treatment of one refractory SPTCL in Chicago by targeting PI3k/AKT/mTOR and the Jak/STAT pathways.56 Dysregulation of the JAK–STAT pathway has already been revealed in the pathogenesis of T-cell lymphomas.56 The activation of the JAK–STAT pathway causes tumor growth, antiapoptotic activities, and metastasis in cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Li et al. demonstrated that mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin and everolimus) reduced the viability of SPTCL cells in a dose-dependent manner in vitro.31 Pralatrexate, a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor with high affinity, was administered in refractory or recurrent SPTCL, in one retrospective study.57

If patients have concurrent HPS, high-dose corticosteroids with cyclosporine A or a stem cell transplant with chemotherapy may succeed in treatment (Table 3).8 In Taiwan, one group revealed that hematopoietic SCT is a suitable method to cure SPTCL patients with HPS and maintains remission for over 30 months.58 Ruxolitinib, a selective JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor for the treatment of myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera, was successful in the treatment of SPTCL patient with HPS, first published in a French case report in 2020.59

| SPTCL with HPS |

|---|

|

In conclusion, immunosuppression-based regimens (MTX and steroid) or chemotherapy-based regimens are considered as a first-line therapy in sporadic SPTCL. If the treatment fails or cancer recurs, cyclosporine A, pralatrexate, and histone deacetylase inhibitors could be used as the second-line therapy. SCT could be considered as well. If HPS is diagnosed, chemotherapy followed by SCT may be indicated. Ruxolitinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, may have an emerging role in treating SPTCL with HPS.

2.5 Treatment outcome

SPTCL generally has a good prognosis and outcome with a 5-year overall survival rate of 85%–91%.8, 22 However, a disease with concurrent HPS and upper extremity involvement may present poor prognosis.25

3 SUMMARY

SPTCL is a rare cutaneous T cell lymphoma, and a life-threatening complication, HPS, may occur. The diagnosis of SPTCL is majorly based on biopsies and immunohistochemistry. The pathophysiology of SPTCL remains unclear. With regard to the treatment of SPTCL, there is no current guideline. Immunosuppressive and chemotherapeutic drugs are most commonly utilized initially. The outcome of SPTCL is generally good but worsens with HPS. In refractory, relapse, or SPTCL with HPS, SCT is an appropriate treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the Information Management Office of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital for assisting with the search of all patients with SPTCL in our hospital.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.-H.H. and E.-C.L. conceptualized the idea of the study. J.-B.L. and Y.-H.F. curated and analyzed the data. E.-C.L. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. C.-H.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.H.H. performed supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital.

INFORMED CONSENT

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available from Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.