The role of stereotactic body radiation therapy in the management of pulmonary metastases: a systematic review

Abstract

While pulmonary metastases are often managed through metastasectomies, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is a relatively novel treatment that has shown promise for this disease. This review aimed to summarize the current findings of SBRT in the treatment of pulmonary metastases. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL were searched for articles that examined the use of SBRT for patients with pulmonary metastases. Primary outcomes included overall survival, disease-free survival, and progression-free survival. Results were pooled where appropriate. Risk of bias was assessed through the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies tool. After screening, 13 studies with 545 patients conducted between 2006 and 2020 were included in this review. Primary tumor localizations included gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and bone, among others. Pooled overall survival at 1 year was 81%, 41% at 3 years, 34% at 4 years, and 26% at 5 years. Pooled progression-free survival at 1, 2, and 3 years was 60%, 41%, and 31% respectively. Local control at 1, 2, and 3 years were 90%, 79%, and 77%, respectively. Preliminary evidence regarding SBRT for treatment of pulmonary metastases shows promising benefits for overall survival and local control. Further high-quality prospective trials are required to investigate the effectiveness and treatment-related adverse effects of SBRT, and should compare it with metastasectomy.

1 INTRODUCTION

The lung is a common site of metastatic disease occurrence.1 Pulmonary metastases may originate from lung cancers or extrapulmonary malignancies, such as colorectal cancer, sarcoma, malignant melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, or germ cell tumors, through lymphovascular or transcoelomic spread.2 Metastasectomies are often involved in the management of lung metastases and have become a common procedure in thoracic surgery, mainly in cases of colorectal cancer with pulmonary involvement.3 Often considered a “standard” in the treatment of lung metastases, there have been several investigations exploring the effectiveness of metastasectomies, most notably the landmark study by Pastorino et al., who reported an overall survival (OS) rate of 36% at 5 years, and 22% at 15 years for 5206 patients postmetastasectomy.1 However, although routinely performed and extensively studied, there remains a paucity of strong evidence on the survival benefit of metastasectomies, with no randomized trials completed to date.3 Furthermore, improved outcomes after metastasectomies have only been shown in a highly selected patient population, and the identification of individuals that would most benefit from surgery has been difficult.3

More recently, less-invasive therapies have been successfully involved in the treatment of lung metastases, which are especially attractive in the cases of patients who are not surgical candidates.4 Chemotherapy and immune therapy have shown potential in treating low-volume metastases, and radiofrequency ablation, cryoablation, microwave ablation, and laser-induced thermal therapy are all techniques that have been utilized as alternatives to surgical intervention.2 One technique that has shown recent promise is stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), which utilizes a summation of a large number of small dose radiation beams within a tight margin.4 As a relatively recent advancement in the realm of cancer treatment, there continues to be a degree of controversy and lack of high-level evidence regarding the involvement and benefit of SBRT. Therefore, this systematic review aimed to summarize and present current evidence on the effectiveness of SBRT in the management of pulmonary metastases.

2 METHODS

2.1 Search strategy

We searched the following databases covering the period from database inception through March 2021: MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL. The search was designed and conducted by a medical librarian with input from study investigators. The search strategy included keywords relating to SBRT and lung metastases (Appendix 1). We also searched the references of published studies and searched gray literature manually to ensure that relevant articles were not missed. This systematic review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta–Analyses (PRISMA) and the Synthesis Without Meta–Analysis (SWiM) guideline.5, 6

2.2 Outcomes assessed

The primary outcomes of interest in this review were OS, disease-free survival, and progression-free survival (PFS) after SBRT. Secondary outcomes included treatment response, recurrence (locoregional and distant), local control (LC), and treatment-related complications. Comparative treatment groups aside from SBRT and specific dosages were also obtained with the purpose of conducting subgroup analyses.

2.3 Eligibility criteria and study selection

Studies were included if they investigated the effects of SBRT on survival, treatment response, or morbidity for patients aged ≥18 years with pulmonary metastases. We included randomized controlled trials and cohort studies (prospective or retrospective). Exclusion criteria included: studies that did not report the use of SBRT, no relevant outcome of interest, studies that did not examine pulmonary metastases, case reports, conference abstracts, editorials, review papers, and basic science articles. We did not discriminate study texts by language.

Study selection based on title, abstracts, and full text was performed in duplicate. At the title and abstract stage, any discrepancies were automatically included to ensure inclusion of all relevant studies. Discrepancies identified at the full-text or data-abstraction stage were resolved by invoking a third independent reviewer to resolve conflicts.

2.4 Data extraction and risk of bias

Data extraction was independently complete by two authors. The following a priori data were abstracted from studies: baseline study characteristics (author, year, country, study type), patient characteristics (age and sex), SBRT fractions and dosage, and location of primary tumors. All data were entered into a standardized data extraction database, and were grouped into study tables based on baseline characteristics, treatment information, outcomes, and risk of bias. Data were synthesized according to study outcome where applicable. Risk of bias was assessed with the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) instrument. Any conflicts between the two independent data extractions were resolved through consensus.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study characteristics

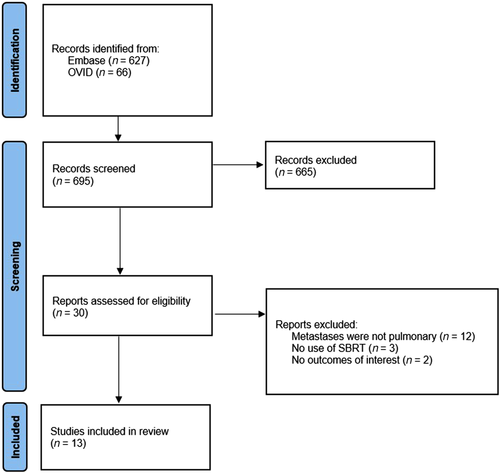

Our initial search yielded 693 potentially relevant citations. After screening was completed, a total of 13 studies with 559 patients were eligible for inclusion after screening.7-19 A PRISMA flow diagram is provided to outline the selection process (Figure 1). All studies were cohort-based, with five of them being prospective and eight being retrospective. One study had a comparison group, with the remainder being single-armed. The studies were conducted between 2006 and 2020. Within the included patients, 40.1% (n = 224) were female, and the median age of all patients was 63 years (range 15.0–89.0 years). The most common primary tumor localizations in patients were gastrointestinal (n = 169), pulmonary (n = 80), bone (n = 59), and head and neck (n = 39). A list of all primary tumor locations, and other patient and study characteristics can be found in Table 1.

| Age, years (SD/range) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study author and date – location | Type of study | Location of primary cancers – N (%) | Type of treatment | N analyzed (# of lesions) | % Female | Mean | Median | Overall follow-up, months (SD/range) |

| Agolli, 2015 – Italy | Retrospective cohort | Lung – 4 (18) | SBRT | 22 (29) | 32 | 66 (52–88) | – | 18 (4–53) |

| Brain – 3 (15.5) | ||||||||

| Adrenal gland – 2 (9) | ||||||||

| Bone – 1 (5) | – | |||||||

| Dhakal, 2012 – USA | Retrospective cohort | Uterine – 6 (12) | S + CT | 37 (–) | 46 | 53 (–) | 56 (18–88) | – |

| Mediastinum – 2 (4) | ||||||||

| Others – 12 (23) Unknown –1 (2) | ||||||||

| SBRT | 14 (74) | |||||||

| Inoue, 2013 – Japan | Retrospective cohort | Intestinal – 37 (42.5) | SBRT | 87 (189) | 41 | – | 63 (34–88) | – |

| Breast – 12 (13.8) | ||||||||

| Head and neck – 9 (10.3) | ||||||||

| Bone/soft tissue – 5 (5.7) | ||||||||

| Testes – 3 (3.4) | ||||||||

| Bladder – 3 (3.4) | ||||||||

| Esophagus –2 (2.3) | ||||||||

| Uterus – 2 (2.3) | ||||||||

| Thyroid – 1 (1.1) | ||||||||

| Ovary – 1 (1.1) | ||||||||

| Melanoma – 1 (1.1) | – | |||||||

| Janssen, 2016 – Germany | Retrospective cohort | Lung – 18 (39.1%) | SBRT | 46 (–) | 39 | – | – | – |

| Colorectal – 13 (28.3%) | ||||||||

| Melanoma – 5 (10.9%) | ||||||||

| Other – 12 (26%) | ||||||||

| Kim, 2008 – South Korea | Prospective cohort | Colorectal – 13(100) | SBRT | 13 (18) | 54 | – | 54 (45–74) | – |

| Kim, 2012 – USA | Retrospective cohort | Head and neck – 5 (23.8) | SBRT | 21 (33) | 52 | – | 61 (42–79) | 20.1 (9.9–36.3) |

| Sarcoma – 4 (19) | ||||||||

| Colorectal – 5 (23.8) | ||||||||

| Breast – 2 (9.5) | ||||||||

| Melanoma – 2 (9.5) | ||||||||

| Lung – 1 (4.8) | ||||||||

| Squamous cell/skin – 1 (4.8) | ||||||||

| Uterus – 1 (4.8) | ||||||||

| Navarria, 2015 – Italy | Prospective cohort | Soft tissue sarcoma – 28 (100) | SBRT | 28 (51) | 53 | – | 64 (23–89) | – |

| Norihisa, 2008 – Japan | Prospective cohort | Lung – 15 (44.1) | SBRT | 34 (-) | 35 | – | 71 (30–80) | – |

| Colorectal – 9 (26.5) | ||||||||

| Head and neck – 5 (14.7) | ||||||||

| Kidney – 3 (8.8) | ||||||||

| Breast – 1 (2.9) | ||||||||

| Bone – 1 (2.9) | – | |||||||

| Okunieff, 2006 – USA | Prospective cohort | Breast – 10 (20.4) | SBRT | 49 (125) | 55 | 60 (-) | 60 (37–86) | – |

| Colorectal – 14 (28.6) | ||||||||

| Lung – 8 (16.3) | ||||||||

| Other – 17 (34.7) | ||||||||

| Rusthoven, 2009 – USA | Prospective cohort | Colorectal – 9 (23.7) | SBRT | 38 (63) | – | – | 58 (29.9–83.3) | 15.6 (6–48) |

| Sarcoma – 7 (18.4) | ||||||||

| Renal cell – 7 (18.4) | ||||||||

| Lung – 5 (13.2) | ||||||||

| Melanoma – 3 (7.9) | ||||||||

| Head and neck – 3 (7.9) | ||||||||

| Breast – 2 (5.3) | ||||||||

| Other – 2 (5.3) | ||||||||

| Siva, 2014 – Australia | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal – 20 (31) | SBRT | 65 (85) | 42 | – | 69 (61–79) | – |

| Lung – 16 (25) | ||||||||

| Head and neck – 7 (11) | ||||||||

| Bone and soft tissue – 5 (8) | ||||||||

| Other – 17 (25) | ||||||||

| Von Einem, 2020 – Germany | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal – 34 (100) | SBRT | 34 (45) | 44 | – | 65 (41–77) | – |

| Zhang, 2011 – China | Retrospective cohort | Lung – 13 (18.3) | SBRT | 71 (172) | 37 | – | 59 (15–84) | – |

| Colorectal – 11 (15.5) | ||||||||

| Head and neck – 10 (14.1) | ||||||||

| Sarcoma – 8 (11.3) | ||||||||

| Hepatic – 8 (11.3) | ||||||||

| Renal cell – 6 (8.5) | ||||||||

| Breast – 5 (7) | ||||||||

| Other – 10 (14.1) | ||||||||

- Abbreviations: CT, chemotherapy; mo, months; N, number of patients; S, surgery; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

3.2 SBRT treatment

SBRT was administered at various degrees within the included studies, and varying methodologies were implemented within each study. The number of dose fractions ranged from one to 10, with the most common being four. Furthermore, the total dosage ranged from 18 to 86.4 Gy, depending on the number of fractions implemented. Although SBRT was the primary treatment used, some studies included adjuvant treatment for certain patients, which included chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. Information on the specific treatment regimen used by each study can be found in Table 2.

| Study author and date–location | Type of study | Type of treatment | N analyzed (no. of lesions) | No. fractions (SBRT) | Total dosage | Other therapies used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agolli, 2015 – Italy | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 22 (29) | 1 for small tumors; 3 for large tumors | 30 Gy; 45 Gy | Chemotherapy in 9 patients |

| Dhakal, 2012 – USA | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 14 (74) | 10 | 50 Gy | Chemotherapy used on some patients after surgery |

| Inoue, 2013 – Japan | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 87 (189) | 4 | 48 Gy | – |

| Janssen, 2016 – Germany | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 46 (–) | 8 | 52.5–86.4 Gy | – |

| Kim, 2008 – South Korea | Prospective cohort | SBRT | 13 (18) | 3 | 39–51 Gy | – |

| Kim, 2012 – USA | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 21 (33) | 3–5 | 40–50 Gy | – |

| Navarria, 2015 – Italy | Prospective cohort | SBRT | 28 (51) | 4 | 48 Gy | – |

| Norihisa, 2008 – Japan | Prospective cohort | SBRT | 34 (–) | 4–5 | 48 Gy or 60 Gy | – |

| Okunieff, 2006 – USA | Prospective cohort | SBRT | 49 (125) | 10 | 50 Gy | 37/49 patients received prior chemotherapy |

| Rusthoven, 2009 – USA | Prospective cohort | SBRT | 38 (63) | 4 | 48–60 Gy | – |

| Siva, 2014 – Australia | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 65 (85) | 1 | 18 Gy or 26 Gy | – |

| 4 | 48 Gy | |||||

| 5 | 50 Gy | |||||

| 7 | 49 Gy | |||||

| Von Einem, 2020 – Germany | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 34 (45) | 1 | 26 Gy | 15 patients had previous radiotherapy |

| Zhang, 2011–China | Retrospective cohort | SBRT | 71 (172) | 3-5 | 30–60 Gy | – |

- Abbreviations: Gy, gray; N, number of patients; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therap.

3.3 Survival outcomes

OS related to SBRT was examined by all included studies to varying extents between a 1- and 5-year follow-up. The pooled OS value at 1 year was 81% (95% CI 73–88%, I2 = 75%, 13 studies), at 3 years it was 41% (95% CI 34–48%, I2 = 50%, 11 studies), at 4 years it was 34% (95% CI 28–40%, I2 = 8%, six studies), and at 5 years it was 26% (95% CI 20–33%, I2 = 15%, 5 studies). Only two studies analyzed this outcome at 8 years, and reported values of 14% and 15%.

PFS was only examined in 50% (n = 650) of the included studies, with a limited number of follow-up points. At 1 year, the pooled PFS was 60% (95% CI 47–72%, I2 = 63%, 6 studies). All seven studies reported on PFS at 2 years and had a pooled value of 41% (95% CI 24–59%, I2 = 84%). At 3 years, the pooled PFS was 31% (95% CI 15–51%, I2 = 81%, 4 studies). One study (n = 87) examined PFS at 4 and 5 years, and acquired values of 28% and 11%, respectively. Information on all survival outcomes can be found in Table 3.

| Study author and date | Type of treatment | N analyzed (# of lesions) | Follow-up in months | Overall survival | Progression-free survival | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | ||||

| Agolli, 2015 | SBRT | 22 (29) | 6 | 95 | 21 | 81 | 18 |

| 12 | 86 | 19 | 79 | 17 | |||

| 18 | 78 | 17 | 38 | 8 | |||

| 24 | 49 | 11 | 4 | 9 | |||

| Dhakal, 2012 | S + CT | 37 (–) | 12 | 33 | 12 | – | – |

| 24 | 17 | 6 | – | – | |||

| 36 | 11 | 4 | – | – | |||

| 48 | 8 | 3 | – | – | |||

| 60 | 8 | 3 | – | – | |||

| 72 | 3 | 1 | – | – | |||

| 84 | 3 | 1 | – | – | |||

| SBRT | 14 (74) | 12 | 80 | 11 | – | – | |

| 24 | 53 | 7 | – | – | |||

| 36 | 46 | 6 | – | – | |||

| 48 | 46 | 6 | – | – | |||

| 60 | 20 | 3 | – | – | |||

| 72 | 14 | 2 | – | – | |||

| 84 | 14 | 2 | – | – | |||

| 96 | 14 | 2 | – | – | |||

| 108 | 14 | 2 | – | – | |||

| Inoue, 2013 | SBRT | 87 (189) | 12 | 77 | 67 | 67 | 58 |

| 24 | 47 | 41 | 40 | 35 | |||

| 36 | 32 | 28 | 28 | 24 | |||

| 48 | 30 | 26 | 28 | 24 | |||

| 60 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 10 | |||

| Jassen, 2016 | SBRT | 46 (–) | 12 | 66 | 30 | – | – |

| 24 | 56 | 26 | – | – | |||

| Kim, 2008 | SBRT | 13 (18) | 12 | 100 | 13 | 46.2 | 6 |

| 24 | 75.5 | 10 | 11.5 | 1 | |||

| 36 | 64.7 | 8 | 11.5 | 1 | |||

| Kim, 2012 | SBRT | 21 (33) | 6 | 100 | 21 | – | – |

| 12 | 90 | 19 | 52 | 11 | |||

| 24 | 78 | 16 | 32 | 7 | |||

| 36 | 40 | 8 | – | – | |||

| Navarria, 2015 | SBRT | 28 (51) | 12 | 89 | 25 | – | – |

| 24 | 56 | 26 | – | – | |||

| 36 | 43 | 12 | – | – | |||

| 48 | 43 | 12 | – | – | |||

| 60 | 43 | 12 | – | – | |||

| 72 | 22 | 6 | – | – | |||

| Norihisa, 2008 | SBRT | 34 (–) | 6 | 100 | 34 | 80 | 27 |

| 12 | 91 | 31 | 47 | 16 | |||

| 24 | 84 | 29 | 35 | 12 | |||

| 36 | 54 | 18 | 30 | 10 | |||

| Okunieff, 2006 | SBRT (all) | 49 (125) | 36 | 83 | 41 | – | – |

| SBRT (curative) | 30 (–) | 12 | 71 | 21 | – | – | |

| 24 | 38 | 11 | 25 | 8 | |||

| 36 | 25 | 8 | 16 | 5 | |||

| SBRT (palliative) | 19 (–) | 12 | 52 | 10 | 21 | 4 | |

| 24 | 19 | 4 | 6 | 1 | |||

| 36 | 6 | 1 | – | – | |||

| Rusthoven, 2009 | SBRT | 38 (63) | 12 | 66 | 25 | – | – |

| 24 | 39 | 15 | – | – | |||

| 36 | 24 | 9 | – | – | |||

| 48 | 24 | 9 | – | – | |||

| Siva, 2014 | SBRT | 65 (85) | 12 | 93 | 60 | – | – |

| 24 | 71 | 46 | – | – | |||

| 36 | 52 | 34 | – | – | |||

| Von Einem, 2020 | SBRT | 34 (45) | 12 | 88 | 30 | 39 | 13 |

| 24 | 65 | 22 | 34 | 12 | |||

| 36 | 52 | 18 | 34 | 12 | |||

| 48 | 43 | 15 | – | – | |||

| 60 | 29 | 10 | – | – | |||

| Zhang, 2011 | SBRT | 71 (172) | 12 | 79 | 56 | – | – |

| 24 | 52 | 37 | – | – | |||

| 36 | 41 | 29 | – | – | |||

| 48 | 34 | 24 | – | – | |||

| 60 | 25 | 18 | – | – | |||

| 72 | 20 | 14 | – | – | |||

| 84 | 15 | 11 | – | – | |||

| 96 | 15 | 11 | – | – | |||

- CT, chemotherapy; N, number of patients; S, surgery; SBRT, stereotactic body radiation therapy.

3.4 Local control and treatment response

Within the included studies, LC was presented as either related to patients or the specific lesion. For LC based on patients, the respective pooled values at 1, 2, and 3 years were 90% (95% CI 86–94%, I2 = 23%, 7 studies, n = 291), 79% (95% CI 69–87%, I2 = 67%, 7 studies, n = 291), and 77% (95% CI 64–88%, I2 = 74%, 5 studies, n = 220).

For LC of lesions, the respective pooled values at 1, 2, and 3 years were 86% (95% CI 75–94%, I2 = 88%, 6 studies, n = 472), 84% (95% CI 76–91%, I2 = 76%, 6 studies, n = 425), and 82% (95% CI 75–89%, I2 = 78, 6 studies, n = 564). Three studies reported on recurrence, and within them 75% (n = 52) of patients experienced some form of recurrence. Four studies provided some information on treatment response; however, reporting was inconsistent. All extracted study data on SBRT treatment response, LC, and disease-free survival can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

3.5 Treatment-related complications

SBRT-related complications were sparsely reported, with just seven studies including any information on it. Of the available data, the prevalent complications were lung fibrosis (35%, n = 10, 1 study), dermatitis (28%, n = 24, 2 studies), atrial arrhythmia (14.3%, n = 3, 1 study), chest wall pain (10%, n = 7, 2 studies), and pneumonia (7%, n = 8, 2 studies). Information on these and the other reported complications can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

3.6 Risk of bias

The risk of bias within the studies was assessed using the MINORS tool. Overall, the 13 non-comparative studies showed a mean score of 11.4, whereas the one comparative study had a score of 18. With a total possible score of 16 for comparative and 24 for non-comparative studies using this instrument, it indicates an overall fair quality of evidence. All studies had a clearly stated aim, adequate patient inclusion, endpoints, follow-up period, and loss to follow-up. However, certain studies did not have a prospective collection of data or a baseline equivalence between groups. Furthermore, no study provided sufficient information on end-point assessment blinding, or calculation of required study size. The comprehensive risk of bias assessment can be found in Table 4.

| Non-comparative studies (max 16) | Comparative studies (max 24) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agolli, 2015 | Dhakal, 2012 | Inoue, 2013 | Jassen, 2016 | Kim, 2008 | Kim, 2012 | Navarria, 2015 | Norihisa, 2008 | Okunieff, 2006 | Rusthoven, 2009 | Von Einem, 2020 | Zhang, 2011 | Siva, 2014 | |

| Clearly stated aim | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Inclusion of consecutive patients | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Prospective collection of data | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Unbiased assessment of study endpoint | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Follow-up period appropriate to aim of study | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Loss to follow up less than 5% | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Prospective calculation of study size | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Adequate control group | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Contemporary groups | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Baseline equivalence of groups | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Adequate statistical analysis | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Total | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 18 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.4 (0.51) | 18 | |||||||||||

- LEGEND: 0 = not reported; 1 = reported but inadequate; 2 = reported and adequate.

4 DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that primarily examines current evidence on the effectiveness of SBRT in the treatment of pulmonary metastases. In this review of 545 patients, the most common primary tumor localizations were intestinal, pulmonary, bone, and otolaryngological. A total of 13 studies were included, and OS ranged from 1- to 5-year follow-up, with two studies looking at 8 years. Overall OS was found to be 81%, 38%, and 26% at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. PFS was reported in half of the included studies and, on average, was found to be 60% at 1 year and 41% at 3 years. PFS at 5 years was 11%, although only reported in one study. When examining patients, overall LC was found to be 90%, 79%, and 77% at 1, 2, and 3 years. Similarly, pooled LC of lesions was 86% at 1 year, 84% at 2 years, and 82% at 3 years. Very few studies reported on SBRT-related complications; however, of the available data, the most common complications were lung fibrosis, dermatitis, atrial arrhythmia, chest wall pain, and pneumonia.

Although this is the first systematic review to evaluate the effectiveness of SBRT in the treatment of pulmonary metastases, studies of a similar nature have been conducted with limited reporting of survival outcomes or a specific primary tumor histology. In a review by Silva et al. focusing on SBRT for pulmonary oligometastases, 2-year weighted LC and OS were reported as 77.9% and 53.7%, which are comparable to the present findings of 79% LC and 57% OS at 2 years.4 Furthermore, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Cao et al. examined SBRT for pulmonary metastases exclusively from colorectal cancer.20 That study reported estimated 3-year OS to be 52%, and LC as 81%, 66%, and 60% at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively.20 Although coinciding with the 3-year OS determined in the current study at 41%, the present findings show a higher LC based on both patients and lesions. This may be attributed to the lower rates of LC noted by the authors when comparing colorectal pulmonary metastases with non-colorectal primaries. Clinical evidence on the use of SBRT in pulmonary metastases have reported analogous findings. A single-institution retrospective analysis of patients with one to three pulmonary metastases found OS at 2 and 3 years was 66.5% and 52.3%, and that LC was 89% and 83.5% after SBRT.21 Similarly, a prospective, multi-institution study determined OS and LC as 54.4% and 81.2% at 2 years in patients with inoperable lung metastases treated with SBRT.22

Metastasectomy remains the current standard in treatment of lung metastases; however, outcome comparisons to SBRT are made difficult by the varying rates of OS reported. One descriptive analysis of metastasectomies found OS to be 96%, 77%, and 56% at 1, 3, and 5 years, whereas an alternate investigation of long-term results after metastasectomy reported OS as 36% at 5 years.1, 23 A systematic review of literature comparing SBRT with surgical approaches determined that there was no difference in short-term survival between pulmonary metastasectomy and SBRT.24 However, the authors noted conclusions could not be drawn regarding the superiority of one therapy over another due to the disparity in SBRT protocols and inherent differences between the two treatment modalities.24 It has also been suggested that there is a lack of strong evidence to support pulmonary metastasectomies as a standard of care. A review of the current literature showed that publications consisted of almost entirely follow-up, with an absence of clinical trials or comparative analyses on metastasectomies.3 Furthermore, study populations were subject to selection bias, as only 2–3% of patients have metastasectomies, and surgical candidacy is determined based on stringent criteria involving favorable patient and disease characteristics.3 Finally, although evidence is sparse, complications of SBRT have a lower degree of morbidity when compared with those associated with pulmonary metastasectomies. Of the reported SBRT complications, we identified that lung fibrosis, dermatitis, atrial arrhythmia, chest wall pain, and pneumonia were the most prevalent. A multicenter prospective study reported similar complications after pulmonary metastasectomies; however, 0.9% of patients underwent reoperation and the overall mortality rate was 0.4%.25 Therefore, when considering the nature of complications associated with invasive procedures, as well as the longer recovery periods after surgery, SBRT might be an appealing alternative for patients already deconditioned by systemic therapies and disease. The promising implications identified in our study prove that further research needs to be conducted on SBRT. Specifically, randomized control trials and comparative analyses investigating the long-term outcomes of SBRT and its effectiveness against traditional therapies may yield firm evidence on benefit, and justify the use of SBRT over metastasectomies when clinically appropriate.

The results of the present systematic review should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. Primarily, a small sample size was acquired, as only a limited number of studies met the inclusion criteria, with many examining only select patient populations. However, our search strategy was created with the intention of capturing a broad range of studies involving SBRT and pulmonary metastases. Although including patients with multiple different primary tumor sites might have created heterogeneity with an unknown effect on our results, doing so was necessary to obtain a sufficient sample size. Therefore, it can be argued that this is not an inherent limitation of this study itself, but rather a result of the general lack of prospective evidence on SBRT, with a majority of existing evidence being observational and retrospective in nature, and lends further justification of the need for clinical investigations involving SBRT. Second, we noted that there was inconsistent reporting of recurrence, treatment response, and complications among the studies included, which might have led to an inaccurate estimation of these variables. Regardless, we did identify that all studies had reliable reporting of OS and LC, which provides a foundation for the potential effectiveness of SBRT in the treatment of pulmonary metastases, but requires further analysis before a conclusion can be drawn. Finally, SBRT treatment methods were different among the studies included, with varying approaches and radiation dosages utilized. Given that SBRT is a relatively new intervention for pulmonary metastases, there is yet to be a consensus on proper dosage and technique. The impact on our results is unknown with limited evidence available, we kept our search strategy broad to capture as many approaches as possible.

5 CONCLUSION

Although pulmonary metastasectomies are considered standard in the treatment of secondary disease occurrence in the lung, there has been recent interest in exploring less-invasive therapies. The use of SBRT is beginning to increase in popularity, with preliminary evidence showing promising benefits to OS and LC. The results of this study can be used as justification for establishing randomized controlled trials, as further high-quality prospective trials are required to fully investigate the effectiveness of SBRT. Future studies should compare the use of SBRT with metastasectomy for pulmonary metastases, and also determine treatment-related adverse effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This paper received no funding for its work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have read the article and there are no competing interests.

APPENDIX 1

SEARCH STRATEGY

-

exp lung/

-

pulmonary.mp.

-

exp pleura/

-

pleural.mp.

-

endobronchial.mp.

-

bronchial.mp.

-

exp metastasis/

-

metastatic.mp.

-

stage 4.mp.

-

stage IV.mp.

-

secondary malignancy.mp.

-

resection.mp.

-

metastasectomy.mp.

-

exp stereotactic body radiation therapy/

-

stereotactic body radiotherapy.mp.

-

sbrt.mp.

-

or/1–6.

-

or/7–11.

-

or/12–16.

-

17 and 18 and 19.