Practical management algorithms for late complications after colorectal and anal cancer—Basic treatment of late complications

Abstract

Background

The aim of this work was to develop a basic treatment guideline set for late complications after treatment for colorectal and anal cancer. Furthermore, a prerequisite was that the guideline was appropriate and safe to use for all health care staff regardless of their educational level. Lastly, the set should cover the most common late complications for patients treated for colorectal and anal cancer, including stool, urinary, sexual, and depressive symptoms.

Methods

The treatment algorithms were developed by doctors in the Late Complication Clinic and afterward they were discussed to establish consensus with external experts in different fields such as surgery, gastroenterology, dietitian, gynecology, urology, sexology, general practice, anesthesiology, and psychiatry.

Results

We have developed a practical basic guideline set covering the most common late complications after colorectal and anal cancer treatment. The guideline set can be used by both nurses and doctors. The treatment algorithms are a combination of ordinary treatment principles and the best possible evidence in the field of late complications after colorectal and anal cancer.

Conclusions

We have developed a basic treatment guideline set for late complications after treatment for colorectal and anal cancers. There is generally little evidence in the field of late complications, and the evidence is mostly based on consensus. To establish higher-level evidence for late complication treatment after colorectal and anal cancer, it is important to monitor and adjust the treatment algorithms.

Abbreviations

-

- EORTC

-

- European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

-

- EQ-5D

-

- European Quality of life—5 Dimensions

-

- LARS

-

- Low Anterrior Resection Syndrome

-

- MDI

-

- Major Depression Inventory

-

- PROM

-

- Patient Reported outcome measures

1 INTRODUCTION

Bowel cancer is a common disease worldwide with around 1.93 million new cases of colon and rectal cancer every year [1]. The survival rates are relatively good after many years of research and development of treatment. The 5-year survival rate for colon cancer is 65%–73%, and for rectum cancer it is 73% [2]. Furthermore, the incidence of anal cancer worldwide is around 50,000 cases per year with a 5-year survival rate of 66% [3]. Because of the high incidence of colorectal and anal cancer and the improved survival rates, there is a growing number of patients living as long-term survivors, and this number is rising every year. As such, many patients with colorectal and anal cancer suffer from late complications either due to the cancer itself or to the treatment.

The most common late complications are bowel, urinary, sexual, and psychiatric symptoms [4-7]. Bowel symptoms may be present in patients undergoing both colorectal and anal cancer surgery as well as after chemo-radiation therapy. In colorectal surgery, overall 50% of the patients experience bowel symptoms such as diarrhea, stool incontinence, increased stool frequency and urgency, decreased stool-flatus discrimination, rectal bleeding, and incomplete evacuation [2]. When patients are treated for anal cancer, they have up to 62% risk of having stool incontinence, urge, and decreased stool-flatus discrimination [8, 9]. Urinary problems such as stress, urge, and overflow incontinence after rectal cancer surgery are not fully explored, but in some studies it is estimated to concern up to 70% of the patients [2, 10, 11], and 45%–48% of patients undergoing chemo-radiation therapy for anal cancer experience urinary incontinence and/or urgency [12]. Rates of sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery in men are estimated variously in the available studies, and it might be up to 76% who have erectile dysfunction and ejaculation problems [11, 13]. For women, there is also a fluctuation in the estimation of sexual dysfunction, and up to 56% can have vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and lower rates of sexual enjoyment after rectal cancer surgery [2, 11, 13]. Sexual dysfunction after anal cancer treatment remains rather unexplored in the literature. However, a single study reported that 67% of patients undergoing treatment for anal cancer experienced sexual dysfunction [9]. Depressive symptoms after colorectal cancer are seen in up to 19% of the patients being more depressed and anxious compared with the general population [2, 14]. After anal cancer treatment, it is reported that 70% of the patients have a lower quality of life [8, 9], and to our knowledge, there are no data available about depressive symptoms in this group of patients. Unfortunately, there is a lack of knowledge and standard care guidelines for bowel cancer survivors due to a small number of high-quality research studies investigating late complications after colorectal and anal cancer [5, 15].

Therefore, the aim of this paper was to present practical basic treatment algorithms for late complications after colorectal and anal cancers. The set of algorithms is meant to cover basic treatment levels, and the target group is nurses and younger doctors. We also aimed that the guideline set should be of low cost for the patient while still providing the best possible evidence-based treatment and including high patient safety.

2 METHODS

In October 2020, we started a nurse-led outpatient clinic for late complications in our surgical department [16]. The clinic invited all patients who had undergone surgery for colorectal and anal cancer. The clinic was operated by two nurses once a week, and once a month a surgeon and a gastroenterologist were available in the clinic. We prepared the patients and clinicians before the visits with a questionnaire based on patient reported outcome measures (PROM). The PROM was composed of validated questions regarding Low Anterior Resection Syndrome [17, 18], St. Marks Incontinence Score [19], Bristol Stool Scale [20], Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms [21], Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms [22], Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms [23], International Index of Erectile Function [24], the Female Sexual Function Index [25], Colostomy Impact Score [26], Rectal Cancer Pain Score [27], Education/labor market/physical activity and social contact [28], EORTC fatigue 12 [29], Major Depression Inventory (MDI) [30], and health-related quality of life–EQ-5D [31].

In addition to preparing the patients and nurses for the visit in the late complication clinic, we also wanted to have a standard set of initial treatment options. We conducted a literature search to identify basic treatment guidelines for late complications [5]. Furthermore, we participated in the development of two recent available treatment guidelines, which were made with a thorough literature search [15, 32]. They covered specialized treatment and not the initial and basic treatment for late complications because such literature did not exist. Since practical sets of basic treatment algorithms for the most common late complications after colorectal and anal cancer treatment were lacking, we decided to develop this as a combination of current practice and best possible evidence in the field of late complications after colorectal and anal cancer. The most common late complications were determined from experiences in the late complication clinic [16]. To develop the guideline set we decided to use a non-formal consensus agreement, we selected experts with expertise from the different fields represented in the guideline set. We also had a representation of the caregivers (nurses) who should provide the guideline set, and the target population (patient associations) who should receive the treatment. The medical experts were employed at the same University Hospital and had the treatment responsibility in their respective clinical fields. We selected experts from the same hospital to ensure that the guideline set was workable in a routine clinical setting, since the individual experts had to cooperate with the patients in the future. All the treatment algorithms in the guideline set were developed between the doctor in the late complication clinic and the experts in the different fields such as surgery, gastroenterology, gynecology, urology, sexology, general practice, anesthesiology, and psychiatry. The guideline set was reviewed and adjusted by nurses providing the care of patients in an outpatient clinic treating late complications, and in the end, the guideline set was also reviewed by patients suffering from late complications.

3 RESULTS

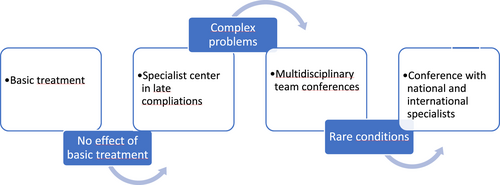

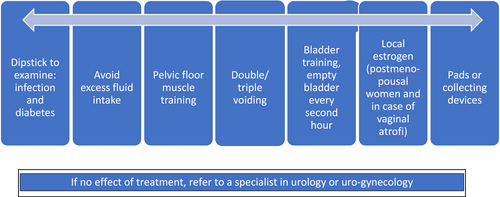

The treatment set described in this paper covers basic treatments for the most common late complication symptoms after colorectal and anal cancer treatment. If the basic treatment does not help the patients, we recommend a referral to a specialist level (Figure 1), and cooperation with specialists in surgery, gastroenterology, dietary, gynecology, urology, oncology, sexology, dermatology, general practice, anesthesiology, psychiatry, and palliative medicine may be beneficial.

Treatment of late complications according to the complexity of the symptoms.

3.1 Basic treatment for bowel symptoms

We have divided the symptoms into four categories (Figure 2): stool incontinence, abdominal pain or bloating, frequent bowel movements and urge, and incomplete emptying.

Basic treatment of stool problems. Follow the arrows to the next box if there is no effect of the treatment in the first box.

Incontinence for stool can be divided into incontinence for loose stool and incontinence for solid stool. When treating incontinence for loose stool, it is important to harden the stool as it will be easier to control bowel movements. The first-line treatment for incontinence is therefore stool regulation (Figure 2) [33, 34]. If there is no effect of stool regulation, we recommend the use of local agents such as small enemas or suppositories, for example, glycerol suppositories. This can help to empty the rectum or neo-rectum and thereby minimize the risk of incontinence. These local agents can be used either after every toilet visit or as required, for example, before the patient leaves home. If there is no effect of the above basic treatment, the patient should be referred to a specialist in functional stool problems and the following can be considered: pelvic floor muscle exercises with biofeedback, trans anal irrigation, or sacral nerve modulation.

Abdominal pain and bloating are often related to constipation. Even though the patients may pass normal stool rated on the Bristol Stool Chart [20], they can be constipated. This may be the case when the constipation is related to the right or transverse colon. For that reason, pain and bloating are treated as if they were constipated (Figure 2). If there is no effect of the basic treatment, and the patient is suffering from pain and bloating to a degree that affects them in daily life, they should be referred to a gastroenterologist (Figure 2).

Frequent bowel movements and urge are often due to loose stool or constipation [33, 34]. Loose stool is difficult to control and hold back; consequently, the patient has frequent bowel movements and urge. If constipation is present, the urge and frequent bowel movements are related to a high fecal load in the colon, which may trigger emptying and thereby frequent bowel movements. First-line treatment is therefore targeted to regulate the stool consistence (Figure 2) [33, 34]. Many patients will benefit from the use of small enemas or glycerol suppositories as these local agents can empty the rectum or neo-rectum, and the patient will have more control of when and where to pass stool because the rectum is emptied. If there is no effect of this basic treatment, the patient should be referred to a specialist in functional stool problems, and pelvic floor muscle exercise with or without biofeedback, trans-anal irrigation or sacral nerve modulation could be considered.

Incomplete emptying occurs when the patient is not able to evacuate all the stool from the rectum. This gives the patient a feeling of incomplete emptying and the patient can suffer from soiling, anal skin rash, and anal itching. Again, it can be due to underlying constipation or loose stool, and the basic treatment is stool regulation (Figure 2) [33, 34]. Often it is not enough to regulate the stool; therefore, the use of small enemas or glycerol suppositories can help the patient to empty the rectum or neo-rectum. If the above treatment does not have any effect, the patient should be referred to a specialist in functional stool problems. The specialist can examine and treat for other causes of incomplete emptying, such as mucosal prolapse, rectocele, or ulceration after radiation therapy. Moreover, loose stool could be caused by other medical conditions, such as colitis, bile acid malabsorption, or small bowel bacterial overgrowth [32]. Patients can also use pelvic floor muscle exercises with or without biofeedback and trans-anal irrigation.

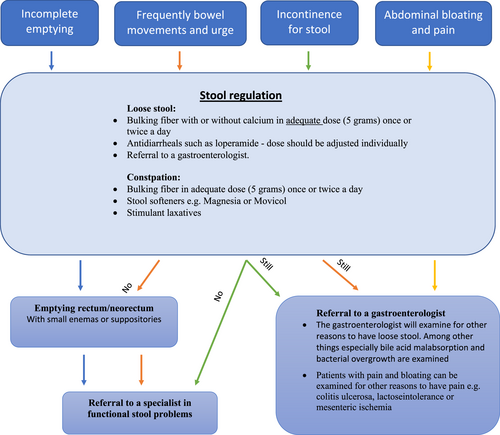

3.2 Basic treatment for urinary symptoms

The following treatment algorithms target patients with urinary problems after pelvic surgery. We have divided the symptoms into three main categories: stress incontinence, urge incontinence, and nocturnal incontinence. All patients presenting with urinary symptoms have a urine dipstick analysis and urine culture to examine and treat underlying urinary infection and diabetes. All patients were also screened for constipation as constipation can induce urine incontinence.

Stress incontinence is defined as urine leak when the patient is physically active, such as when coughing, laughing, sneezing, running, or when heavy lifting. This activity puts pressure (stress) on the bladder and the patient may leak urine. After surgery, it can be due to iatrogenic damage to the urethral sphincter and pelvic floor muscles. Yet another reason to experience stress incontinence after surgery may be bladder overflow, possibly due to altered sensation of the bladder because of damage to the nerves around the bladder and consequently the patient might not sense when to empty the bladder, the bladder volume can also be diminished due to surgery. Urge incontinence after pelvic surgery can also be due to iatrogenic nerve injury and thereby loss of control of the voiding reflexes. The symptom is a sudden and intense urge to urinate followed by involuntary leakage of urine [10].

The basic treatment for stress and urge incontinence is similar. Treatment is firstly based on the patient's fluid intake and urine output chart [10, 35]. Often basic corrections can be performed such as less fluid intake and regular voiding routines each or every 2 h to avoid overflow. The patients are also instructed to do double or triple voiding by use of abdominal pressure. Pelvic floor muscle training for both men and women is recommended [35] (Figure 3). In patients with fewer symptoms, the use of pads and collecting devices can be an option [35]. Specific for postmenopausal women and women with vaginal atrophy for other reasons, for example, radiation therapy, local estrogen is recommended [36] (Figure 3). If the patients have no effect of the above treatment, they should be referred to a urologist or uro-gynecologist.

Basic treatment of urine incontinence.

Nocturia can be a problem if a patient is emptying the bladder more than once during the night. Nocturia can be due to large amounts of fluid intake in the evening, general edema, untreated diabetes, urinary infection, or bladder overload. Basic treatment seeks to lower the urine production at night. Therefore, the patients are told to avoid inappropriate fluid intake in the evening, illustrated by a fluid intake and urine output chart. If the patient has general edema, it can generate a large urine output at night [10, 35]. Therefore, the treatment of general edema with diuretic medicine 6 h before bedtime can be a choice (Figure 3). If the patients have no effect of the basic treatment, they should be referred to a specialist in urology.

3.3 Basic treatment for sexual dysfunction

People have different sexual needs and the sexual need fluctuates during life. For that reason, it is different how patients react to altered sexual function after illness and treatment.

3.3.1 Sexual dysfunction in women

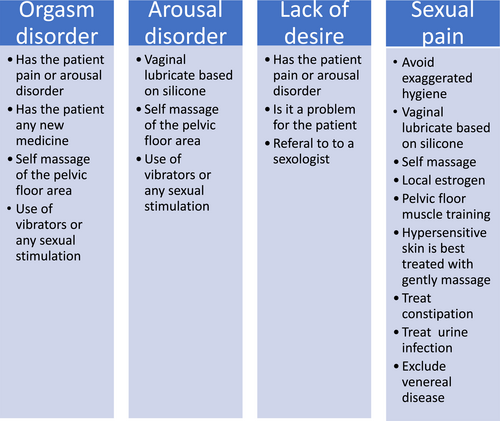

We have divided the sexual symptoms into four categories (Figure 4): sexual pain, orgasm disorder, arousal disorder, and lack of desire [25].

Basic treatment of sexual dysfunction in women.

Sexual pain can be due to vaginal dryness, radiation therapy, injury after surgery, or other reasons such as constipation, infection, or pelvic floor myalgia. Vaginal dryness is common in postmenopausal women, but it also occurs in younger patients treated for pelvic cancer because of chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and maybe even surgery can indirectly cause vaginal dryness because of nerve damage [12]. The symptoms of vaginal dryness are multiple, such as irritation, itching, burning, and pain during sexual stimulation and penetration, and difficulties in achieving sexual arousal. The basic treatment of vaginal dryness is to avoid exaggerated hygiene of the vagina and avoid the use of soap. Also, women should not use things that dry out the vagina such as tampons. We recommend vaginal lubrication based on silicon or hyaluronic acid therapy [37]. It can be used daily to prevent pain during daily activities such as walking. It can also be used when having sexual intercourse. We encourage the patients to stimulate the vagina with massage or any sexual stimulation to increase the blood circulation and thereby stimulate the mucous membrane to build up. If vaginal pain and dryness are due to lack of hormones, a local application of estrogen is recommended [38] (Figure 4). Radiation therapy can cause pain because of severe dermatitis, the wall in the vagina can be rigid and stiff, and in severe cases, agglutination and stenosis of the vagina can occur. The basic treatment is pelvic floor muscle training, and we encourage the patient to stimulate the vagina with massage and other sexual stimulation. Furthermore, we recommend treating hypersensitive skin with gentle massage, and by the time they will experience less pain by touch [37]. The severe cases should be referred directly to a gynecologist [37, 39]. Other reasons for sexual pain should be considered, such as constipation, myalgia, urinary infections, or venereal diseases. If the patients have no effect of the above treatments, they should be referred to a specialist in gynecology (Figure 4).

Orgasm disorder can be due to surgery and radiation therapy in the pelvis, which can damage skin and nerves. This can reduce the sensation, and when sensation is reduced, it is harder to achieve orgasm. The lack of orgasm can be secondary to sexual pain, arousal disorder, or lack of desire. If that is the case, treatment should be specifically pointed to that. Some medications can cause orgasm disorder, such as heart medications, anti-depressives, hormone treatment, and painkillers. The general treatment of orgasm disorder is to restore and enhance the sense of touch. Therefore, patients are instructed to do any or all of the following: self-massage of the pelvic floor area, use of vibrators, and sexual stimulation. Whenever the patient stimulates the area, the sense of touch is increased and there is a higher possibility of achieving orgasm. If the patient has no effect of the above treatment, they should be referred to a specialist in gynecology or sexology if available (Figure 4).

Sexual arousal describes how excited or turned on you get when you anticipate sex. When women become highly aroused, the blood flow increases to the genitals, triggering a spontaneous response of the vagina that releases a natural lubricant, vaginal enlargement and swelling of the vulva. Subjective arousal is how the woman feels about her bodily experience. Patients with arousal disorders are recommended to use vaginal lubrication, and they are instructed to do any or all of the following: self-massage of the pelvic floor area, to use vibrators, or to do any sexual stimulation. If the patient has no effect of the above treatments, she should be referred to a specialist in gynecology or sexology, depending on if it is related to physical or psychological factors (Figure 4).

Cancer treatment, medication, surgery, and tiredness after cancer treatment are all factors that can interfere with sexual desire, and it can be very difficult to maintain intimacy with a partner when the patient uses all resources to be healthy again. Low sexual desire generally shows up as a constant lack of sexual fantasies and disinterest in sexual activity. For patients with cancer, it is normal to lack sexual desire for a shorter or longer period. It is important to clarify whether the lack of desire is related to other factors such as pain or lack of arousal [40] (Figure 4). If the patient has no organic cause to lack desire and find that as a problem, the patient should be referred to a specialist in sexology.

3.3.2 Sexual dysfunction in men

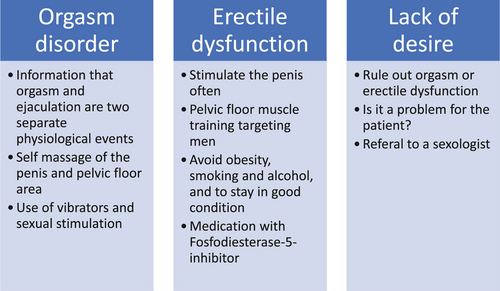

We have divided the symptoms into three categories (Figure 5): orgasm disorder, erectile dysfunction, and lack of desire.

Basic treatment of sexual dysfunction in men.

Mostly, men have orgasm and ejaculation at the same time, and orgasm and ejaculation typically occur 4–10 min after the start of stimulation. All men can experience a lack of orgasm or ejaculation every now and then. It is only a problem if it occurs often and if it interferes negatively with the overall sexual satisfaction. The general treatment of orgasm disorder is to restore and enhance the sense of touch. Patients are instructed to do any or all of the following: self-massage of the penis and pelvic floor area, use of vibrators, and sexual stimulation. Whenever the patient stimulates this area, the sense of touch is increased, and thus, there is a higher possibility of an orgasm over time (Figure 5).

Erectile dysfunction in patients treated for pelvic cancer can be due to physical changes after surgery, radiation therapy, or medication, but it can also be psychogenic. As for all other patients, it can also be due to diabetes, hypertension, atherosclerosis, obesity, smoking, alcohol abuse, medication such as antipsychotics, heart medications, anti-depressives, and hormones. In patients with physical origin of erectile dysfunction after treatment for cancer, symptoms normally occur immediately after the treatment [41]. Symptoms are weak erection, so weak it is not possible to conduct intercourse. The patient may lack morning erection but typically have normal libido. The treatment of erectile dysfunction should start early to avoid irreversible erectile dysfunction due to neuropraxia and/or affection of cavernous nerves resulting in hypoxia of the corpora cavernosum and permanent changes in the corpora cavernosum [42]. After pelvic surgery, it seems like there can be a better erectile function up to 2 years after surgery [42]. The patients are instructed to stimulate the penis often, and a weak erection is better than no erection. The patients are recommended to do pelvic floor muscle training targeted on men. Furthermore, we prescribe fosfodiesterase-5-inhibitor if the patients have no contraindications [41], and generally, we recommend avoiding obesity, smoking, and alcohol abuse to stay in a good physical condition. If the patients do not have any effect of the above mentioned, they are referred to a specialist in urology (Figure 5).

As for women, lack of desire is common during and after cancer treatment. It is important to clarify if the lack of desire is related to other factors, such as erectile dysfunction or orgasm disorder, which is to be treated otherwise. If the patients have a lack of desire and find that as a problem, the patient should be referred to a specialist in sexology.

3.4 Basic treatment for depressive symptoms

It is considered normal to be psychologically stressed after treatment for colorectal and anal cancers. In order to estimate the severity of the patient's psychological state and find patients with clinically significant symptoms of depression, we recommend patients to self-estimate depressive symptoms, such as MDI [30], health-related quality of life – EQ-5D [31], or other similar tools. Patients with mild depressive symptoms can benefit from consultations with a nurse trained to execute these essential conversations, but some symptoms are self-limiting. For patients with moderate or severe symptoms, we recommend a referral to the patient's general practitioner or psychiatrist to continue diagnosis and treatment [14]. In case the patient is suicidal or is considered to have a severe depression requiring acute help, the patient will be directly referred to a psychiatrist or a psychiatric hospital.

4 DISCUSSION

We have described a practical set of algorithms for basic treatments for late complications after colorectal and anal cancer. The guideline set is easy to implement and can be used by health providers at every level, both by skilled and less experienced personnel. We believe it is easier to ask patients about taboo subjects such as stool, urine, and sexual challenges when a guideline set exists including recommendations for when to refer patients for specialized treatment. The fact that this guideline set is designed to be used by nurses and that there is a low cost connected to the different treatments makes it easy and accessible to provide basic treatment for patients with late complications after colorectal and anal cancer. When treating late complications related to cancer, it is always important to consider any new symptoms as a risk of recurrence of cancer or development of a new cancer.

The strengths of this guideline set are that we have described the overall basic treatments for late complications after colorectal and anal cancers. These treatments have low cost and are at low risk of patients. The algorithms are based on the best available evidence. The algorithms are easy to approach and can be used in most outpatient clinics. Some might find this algorithm set to be simple and superficial, but it is our experience that many patients benefit from these basic recommendations. We also experience a demand from both patients and health providers for simple guidelines which can cover most of the basic needs for these patients. Nevertheless, for most of the algorithms there is only little scientific evidence, as they are mostly based on consensus and experiences. As we have not finalized the follow-up on the effects of these algorithms, there is a possibility that some of the recommendations will be adjusted according to our findings. This information will be available in the coming years. Because there is currently little evidence in this field and since the health care providers do not agree on what late complication treatment should cover [15, 32, 43], we did not find it possible to do a formal consensus agreement about basic treatment. However, in the future, when there will be more evidence about the basic treatment of late complications, we would recommend that formal clinical guideline development for basic treatment such as international Delphi rounds should be performed [44].

With this practical guideline set with cheap and easy assessable treatments we have met some of the challenges that may keep some of the health care providers from treating late complications, such as increased workload for the health providers and the increased financial burden of providing care for cancer survivors [5, 38, 45, 46]. Thus, with this guideline set we have made it possible to perform basic treatment for patients with late complications, and the patients do not need to be met with an array of different assessments and treatment modalities depending on the knowledge of the specific healthcare provider they visit [47, 48]. Moreover, as some late complications are not well known to healthcare providers, they will often be left undetected and not treated, but with more focus on the subject and more research we are able to distribute the knowledge [9].

We have implemented a late complication clinic, which is led by dedicated nurses. In our clinic, we screen survivors of colorectal and anal cancer for symptoms for 3 years after surgery and provide treatment when needed and desired by the patients. In our opinion, basic treatment for late complications should be performed in any surgical and oncological department treating colorectal and anal cancers. Patients who do not benefit from basic treatment should be referred to a specialized center for late complications. Such a specialized center for late complications should offer multidisciplinary conferences as well as individualized consultations, and the multidisciplinary team should consist of specialists in surgery, gastroenterology, urology, dietary, gynecology, sexology, psychiatry, dermatology, anesthesia, general practice, and palliative care. Options for multidisciplinary treatment should be an established part of these specialized clinics.

In this paper, we have presented a set of algorithms to treat late complications after colorectal and anal cancer. The treatment is basic and can be increased to a specialized level when needed. Because the algorithms only include basic treatment, it is important to have a supplementary structure for referring more complex cases to a specialized team.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Birthe Thing Oggesen: Conceptualization, data curation, visualization (lead); writing – original draft. Marie Louise Sjødin Hamberg: Data curation (supporting); investigation (supporting); writing – review & editing. Jacob Rosenberg: Data curation (supporting); project administration (lead); writing – review & editing (supporting).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the valuable support and help by Anne Kjærgaard Danielsen, who died during the research process. We hope we did you proud.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Jacob Rosenberg: Professor Jacob Rosenberg is a member of the Medicine Advances Editorial Board. To minimize bias, he was excluded from all editorial decision-making related to the acceptance of this article for publication. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

N/A.

INFORMED CONSENT

Not applicable.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data (papers and web pages) used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.