Gaps in the protection of the amphibians of Myanmar—threat status, endemism, protected area coverage and One Plan Approach conservation

缅甸两栖动物保护之不足——受威胁状况、特有性、保护区覆盖范围及“一揽子保护计划”(One Plan Approach)

Editor-in-Chief & Handling Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Abstract

enCurrently, 41% of amphibian species are threatened with extinction, leading to the ongoing amphibian crisis. In Myanmar, the amphibian diversity is still poorly understood, and, as a result, many conservation gaps remain. To increase the knowledge about Myanmar's amphibians and thus provide an opportunity to fill the gaps in conservation in the country, we assess the species in greater detail. To do so, we compile a species list of the amphibians of Myanmar through various sources and evaluate their threat status using the IUCN Red list. We perform richness analyses to compare the distribution areas of the amphibian species of Myanmar to the distribution of the protected areas (PAs) in the country. We evaluate the representation of Myanmar's amphibians in zoos worldwide through the Zoological Information Management System (ZIMS) to check the implementation of the One Plan Approach to Conservation. Our results suggest that there are 152 amphibian species extant in Myanmar, of which 25 are endemic to the country. 4.6% (n = 7) of all species are classified as threatened, but counting those with insufficient available data as possibly threatened increases the number to 44.1% (n = 67). Of them, 40 species are not covered by any of Myanmar's PAs. That includes 28.6% of the threatened, 35.7% of the potentially threatened, and 48% of the endemic species. According to the ZIMS database, none of Myanmar's threatened, potentially threatened, or endemic amphibian species are kept in any zoo or aquarium worldwide, suggesting that the One Plan Approach is not sufficiently implemented as a conservation measure for Myanmar's amphibians. With this study, we show conspicuous gaps in the protection of Myanmar's amphibians and provide a list of the 36 most threatened species, recommending a possible prioritization for upcoming conservation actions.

摘要

zh目前有41%的两栖动物物种面临灭绝之虞,且不见缓解。缅甸对两栖动物的多样性所知甚少,因此在保护方面仍有诸多不足。为了增进对缅甸两栖动物的了解,从而弥合该国在这方面的缺失,我们对此类物种展开更详尽的评估。为此,我们收集了多方数据,编制了缅甸两栖动物物种清单,并使用IUCN红色名录评估了它们的受威胁状况。我们进行了丰富度分析,将两栖动物分布区域与缅甸自然保护区的分布进行对比。我们通过动物信息管理系统(ZIMS)评估了缅甸两栖动物在全球动物园的比例,以检查“一揽子保护计划”的实施情况。评估显示,缅甸现存152种两栖动物,其中25种属于该国的特有种,4.6%(n = 7)被列为“受威胁”物种,但若将现有数据不足的物种视为“可能受威胁”,则该占比将攀升至44.1%(n = 67)。有40个物种栖息于缅甸的保护区之外,包括28.6%的受威胁物种、35.7%的潜在受威胁物种和48%的特有种。根据ZIMS数据库,缅甸的受威胁、潜在受威胁,或特有的两栖动物物种在全球的动物园或水族馆中均无饲养,表明该国两栖动物的“一揽子保护计划”保护措施没有得到充分落实。通过这项研究,我们指出缅甸在两栖动物保护方面的明显不足,列出包含36种最受威胁物种的清单,可为今后的保护行动提供优先级参考。

Plain language summary

enCurrently, 41% of amphibian species are threatened with extinction, leading to the ongoing amphibian crisis. The amphibians of Myanmar are not well studied, and as a result, many conservation gaps remain. To increase the knowledge about Myanmar's amphibians and thus provide an opportunity to fill the gaps in conservation in the country, we assess the species regarding their diversity, distribution, threat status, and their protection through protected areas (PAs), laying particular focus on endemic species (species only occurring in Myanmar). We found that 44.1% of Myanmar's amphibian species can be classified as possibly threatened, including 88% of the endemic species. Furthermore, 26.3% of species are not protected through any PA, including 48% of the endemic species. Most of these unprotected species are found in the south of Myanmar, which is why extended protection measures should concentrate on this part of the country for the time being. This study also compiles a list of the most threatened species, which should be used as a reference point for prioritization as well.

简明语言摘要

zh目前有41%的两栖动物物种面临灭绝之虞,且不见缓解。当前对缅甸两栖动物的研究还不够深入和全面,保护方面存在诸多不足。为了增进对缅甸两栖动物的了解,从而弥合该国在这方面的缺失,我们评估了物种的多样性、分布、受威胁状况以及自然保护区现状,尤其关注特有种(仅出现缅甸的物种)的生存状况。我们发现缅甸44.1%的两栖动物物种可被归类为“可能受威胁“,其中包括88%的特有种。此外,有26.3%的物种不栖息于任何保护区内,包括48%的特有种。这些未受保护的物种大多发现于缅甸南部,因此,新增的保护措施应集中于这些地区。本研究还编制了一份最受威胁物种清单,应将其作为自然保护优先等级的重要参考。

Practitioner points

en

-

44.1% (67 species) of Myanmar's amphibian species can be classified as possibly threatened, this includes 88% of the endemic species.

-

40 species of Myanmar's amphibians are not protected through any protected area, this includes 48% of the endemic species.

-

Most of the unprotected amphibian species are located in the South of Myanmar.

-

The One Plan Approach is not sufficiently implemented as a protective measure for Myanmar's amphibians.

-

This study provides a list of the 36 most threatened amphibian species, recommending a possible prioritization for upcoming conservation actions.

-

More information is needed about Myanmar's amphibian species and more protection measures should be put in place for them.

实践者要点

zh

-

缅甸44.1%(67种)的两栖动物可被归类为“可能受威胁”,其中包括88%的特有种。

-

40种缅甸两栖动物不栖息在任何保护区内,其中包括48%的特有种。

-

大多数未受保护的两栖动物物种生活在缅甸南部。

-

作为缅甸两栖动物的一项保护措施,“一揽子保护计划”并没有得到充分落实。

-

本研究列出了36种最受威胁的两栖动物物种,建议以此为据,对今后的保护行动进行优先等级排序。

-

需要进一步了解关于缅甸两栖动物的信息,并为它们采取更多保护措施。

1 INTRODUCTION

According to the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, 41% of amphibian species face an imminent risk of extinction (IUCN, 2023). Considering the number of amphibians listed as data deficient, the number of threatened amphibian species is estimated to be 55% (Silla & Byrne, 2018), which would correspond to over 4750 species. They are particularly vulnerable because of narrow habitat preferences and limited distributions (Meredith et al., 2016; Sheridan & Stuart, 2018), as well as their specific needs towards those habitats regarding conditions of moisture, temperature, pH, refuge, and food (Bishop et al., 2012). The permeability of their skin makes them unable to withstand significant changes in these factors, but, at the same time, they occupy the ecosystems currently experiencing the most drastic changes: freshwater ecosystems in tropical forests (Bishop et al., 2012; Meredith et al., 2016). A further problem results from their incomplete and still poorly understood taxonomy (Mulcahy et al., 2018). Amphibians comprise many cryptic species. Therefore, possibly threatened species may be overlooked and are driven to extinction before being recognized (Stuart et al., 2006). Furthermore, the available data on many already recognized species is still scarce likely hampering conservation efforts. This is particularly dangerous considering species with insufficient data are more likely to be threatened than species assessed adequately (Bland et al., 2014, cited after Meredith et al., 2016).

The causes of the amphibian crisis are numerous and include anthropogenic threats like habitat change, habitat destruction, or habitat loss (e.g., Auliya et al., 2023; Cheng et al., 2011; Zaw et al., 2020), overexploitation and the trade underlining it (e.g., Auliya et al., 2023; Rao et al., 2014; Silla & Byrne, 2018; Zaw et al., 2020). The trade entails risks, like the release of specimens in naïve habitats, therefore possibly displacing native species (Ribeiro et al., 2019) through predation, competition, or the introduction of diseases (Bishop et al., 2012; Collins & Storfer, 2003). Other general threats to amphibians around the world are pollution through (chemical) contaminants, and climate change (e.g., Blaustein et al., 2010; Hayes et al., 2010; Luedtke et al., 2023).

Countermeasures aimed at halting the extinction of amphibians include the establishment of protected areas (PAs), conservation breeding, the spreading of education and awareness about the amphibian crisis, legal protection, and policies, especially regarding the trade in amphibians (Fog & Wederknich, 2016; Hussain & Pandit, 2012; Silla & Byrne, 2018; Stiles et al., 2016). The approach of conservation breeding is auspicious as it has been successfully established for several threatened amphibian species (Silla & Byrne, 2018). It may be “the only practical conservation option left for some species whose habitats are dwindling” (Schwartz et al., 2017). Through this, it is possible to integrate ex-situ and in-situ conservation measures and follow the One Plan Approach to conservation, developed by the Conservation Planning Specialist Group (CPSG) of the IUCN (Byers et al., 2013). A multi-methodological approach that attempts to develop management strategies and conservation measures that combine the protection of wild populations and that of ex-situ populations (e.g., populations kept in a zoo) (CPSG, 2024a). It has been suggested in previous studies as an important conservation measure for amphibians (e.g., Krzikowski et al., 2022) and the case study on the Pickersgill's reed frogs in South Africa is one example showing the success of this approach (see CPSG, 2024b).

The establishment of integrated conservation measures focuses on the Southeast Asian area, among others, as it contains multiple biodiversity hotspots but at the same time faces one of the highest deforestation rates in the world (Krzikowski et al., 2022; Sheridan & Stuart, 2018). The largest country of mainland Southeast Asia that is often overlooked in studies concerning the area (A. Poyarkov Jr. et al., 2019; Zaw et al., 2019; Zug, 2022) and still has many conservation gaps, especially regarding its herpetofauna (Mi et al., 2023), is Myanmar (formerly Burma). It harbors approximately 150 species of amphibians (Zug, 2022), is an important component of the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot (Gan et al., 2020), and contains a diversity of ecosystems with lowland and montane habitats and varying climatic conditions (Huang et al., 2021; Huang, Morley, et al., 2023; Mandle et al., 2017).

Herpetologically, Myanmar is not well studied (Gan et al., 2020; Mulcahy et al., 2018; Zaw et al., 2019). The first more extensive studies of the herpetofauna in Myanmar started in 1997 with the research of Joseph B. Slowinski and George R. Zug (in collaboration with the Chatthin Wildlife Sanctuary staff). The Myanmar Herpetology Survey (MHS) of G. R. Zug started formally in 1999 and ended in September 2010. Daniel G. Mulcahy conducted further studies on a larger scale, like herpetological surveys of southern Tanintharyi, in collaboration with Fauna & Flora International's Myanmar Programme. The more open policy of the Myanmar government allowed further studies by other zoologists, such as the surveys of the karst habitats of Cyrtodactylus and other geckos by L. Lee Grismer's group. Other studies on Myanmar have been conducted, for example, by Steven G. Platt, Nikolay A. Poyarkov, Gunther Köhler, and their teams. But, since the return of the military to Myanmar in 2021, further studies are difficult to conduct, and the knowledge about the herpetofauna in Myanmar will remain incomplete (Zug, 2022).

However, planning conservation actions depends on accurate data to successfully counter population declines (Schwartz et al., 2017). To increase the knowledge of the herpetofauna of Myanmar and thus provide an opportunity to fill the gaps in conservation in this country, following the approach by Krzikowski et al. (2022) for the amphibians of Vietnam, this study assessed the amphibians of Myanmar regarding their distribution, their threat status according to the Red List of the IUCN, and their protection through PAs and different legislations and efforts, laying particular focus on endemic and threatened species. Considering the mentioned concept of the One Plan Approach to combine in-situ and ex-situ conservation, the representation of the amphibian species extant in Myanmar in zoos and aquariums worldwide was also conducted. Finally, we compiled a list of the amphibian species that are most at risk of extinction and should, therefore, be prioritized when planning future conservation measures in Myanmar.

2 MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1 Species list

First, a species list was created based on Zug (2022) and Amphibian Species of the World (Frost, 2023). Species only listed as possibly or probably occurring in Myanmar were excluded. In the next step, the list was cross-checked with those species marked as “Extant” in Myanmar by the IUCN Red List. This species list was then refined, starting with the species not matching between the three sources. Further sources were used in this process, like the website Amphibia Web (2023) and recent papers (A. Poyarkov Jr et al., 2019; Al-Razi et al., 2020; Chunskul et al., 2021; Dever, 2017; Dinesh et al., 2020; Gan et al., 2020; Garg & Biju, 2021; Hasan et al., 2019; Huang, Liu, et al., 2023; Köhler, Vargas, et al., 2021; 2021; Lalremsanga, 2022; Lalronunga et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020; Lyu et al., 2023; Mahapatra et al., 2022; Mahony et al., 2022; McLeod, 2010; Mogali et al., 2022; Muansanga et al., 2021; Mulcahy et al., 2018; Ojha et al., 2021; Pham et al., 2020; Rahman et al., 2022; Rao, 2022; Sailo et al., 2022; Schmitz & Ziegler, 2016; Sheridan & Stuart, 2018; Tang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Wangyal & Jamtsho, 2022; Wu et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022; Yu et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022; Zug & Mulcahy, 2020). The taxonomy of the online reference “Amphibian Species of the World” (ASW) from the “American Museum of Natural History” was adopted unless more recent papers suggested a different taxonomy. The cut-off date for the list was set for December 5, 2023. The final species list can be found in the Supporting Information S1: SI1.

The list was later analyzed to determine how many different families of the three orders of amphibians occur in Myanmar and how many species of each family are represented in the country. We analyzed the species list and their threat status (see below) using the program R version 4.3.0 (R Core Team, 2023) and RStudio (2023), and the packages “ggplot2” (Wickham, 2016), “ggrepel” (Slowikowski, 2023), “tidyverse” (Wickham et al., 2019), “dplyr” (Wickham et al., 2023), “ggforce” (Pedersen, 2022), and “scales” (Wickham et al., 2022).

A second list was created containing the species excluded from the official list because they were only listed as possibly or probably occurring in Myanmar in the sources used. The list also includes species where there were discrepancies between the different sources that could not be clearly elucidated until December 5, 2023, as there are still some gaps in the knowledge of some species. However, those species most likely occur in Myanmar as well and therefore should not be forgotten. The list can be found in the Appendix (SI2).

2.2 Distribution

Richness analyses were performed to compare the distribution areas of the amphibian species of Myanmar to the distribution of the PAAs in Myanmar. Therefore, the distribution data of most species was downloaded from the IUCN (2023). The distribution of species that were missing a polygon shapefile or point data in Myanmar or were not listed on the IUCN at all was assessed through literature confirming their occurrence in Myanmar, Amphibia Web (2023), and The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, 2023) (SI3). For the species Amolops latopalmatus, Feihyla wuguanfui, Kurixalus yangi, Leptobrachium rakhinense, Microhyla hmongorum, Micryletta aishani, Nanorana chayuensis, Occidozyga magnapustulosa, Odorrana andersonii, Oreolalax jingdongensis, Polypedates braueri, and Sphaerotheca cf. breviceps no specific coordinates were found and they were excluded from the spatial analyses. Sphaerotheca cf. breviceps represents most likely a cryptic species currently hidden under the name. The nominal form is unlikely to be found in Myanmar.

For each species, we downloaded habitat information from the respective IUCN Red List accounts using the “rredlist” package for R (Gearty et al., 2022). Subsequently, distribution and habitat information was combined by first rasterizing all vectorized distribution information in R using the “terra” package (Hijmans, 2023) to match the spatial resolution of gridded habitat data (Jung et al., 2020) matching the IUCN habitat categories. Finally, the number of species per grid cell of 100 × 100 m was summarized by overlaying all presence-absence maps.

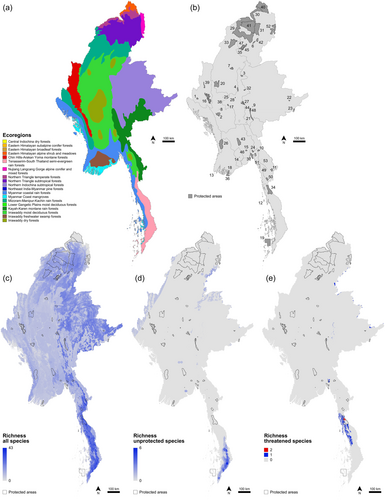

The PA information of Myanmar was taken from UNEP-WCMC and IUCN (2023), and the distribution of the species was described using the ecoregions of Myanmar (see Figure 1a).

We also analyzed which of the threatened, potentially threatened, and endemic species are protected by a PA and which are not. In this process, the mentioned species without a polygon or specific coordinates for Myanmar were excluded.

2.3 Endemism

Patterns of endemism may help prioritize conservation efforts (Morrone, 2008), as species with small distributions are particularly vulnerable to changes in their environment (Wake & Vredenburg, 2008) and therefore need specific conservation actions to prevent extinction. Considering the vulnerability of endemic species, this study focused on the species endemic to Myanmar and differentiated between three extents of endemism: species distributed in two or more ecoregions were classified as “Country Endemic” (CE), species only occurring in one ecoregion but in multiple different locations within this ecoregion were classified as “Regional Endemic” (RE), and species only occurring in one specific location (one specific village or township or only the type locality) were classified as “Microendemic” (ME).

2.4 Threat status

To classify the threat status of the species in Myanmar, this study used the threat status given in the IUCN Red List. The nine categories into which the species can be classified are: Not Evaluated (NE), Data Deficient (DD), Least Concern (LC), Near Threatened (NT), Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), Critically Endangered (CR), Extinct in the Wild (EW), Extinct (EX). Species classified as VU, EN, or CR were considered as threatened with extinction. The threat status is considered outdated 10 years after the last assessment (IUCN, 2023). The IUCN Red List status for each species was collected on August 28, 2023, and updated on December 5, 2023. These data were analyzed by comparing the number of species in each category, once for all amphibian species occurring in Myanmar and once specifically for the endemic species only.

As described above, the trade in amphibians significantly impacts their population declines. Therefore, the three appendices of CITES (The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) were searched for amphibian species occurring in Myanmar to further investigate the threat statuses of the species (CITES, 2023a). Myanmar joined the convention on June 13, 1997 (CITES, 2023b).

2.5 Zoological information and management system analysis

The One Plan Approach suggests to combine in-situ and ex-situ conservation efforts. Therefore, the number of amphibian species and their respective individuals kept in zoos and aquariums around the world was determined through the Zoological Information and Management System (ZIMS). The number of zoos and aquariums keeping species occurring in Myanmar and the numbers of specifically endemic and threatened species were also determined. The data was updated on December 15, 2023.

ZIMS is a web-based information system that zoos, aquariums, and wildlife institutions use to collect information about the animals they keep (ZIMS, 2023). While ZIMS contains the most extensive set of data for ex situ populations of wildlife worldwide, the use of ZIMS is not mandatory. So, not all ex situ populations and individuals can be found in the system. It is also important to note that the system is not always entirely up to date, as the institutions often do not report every change in their populations right away.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Species richness

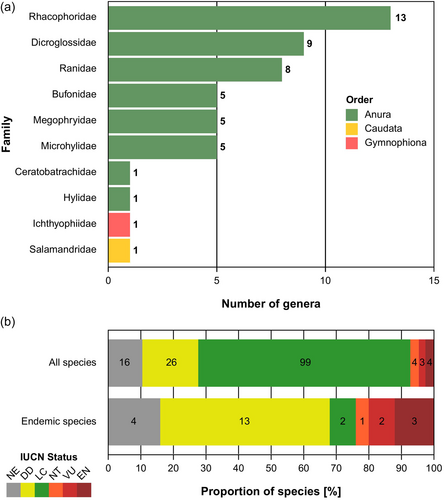

There are 152 amphibian species recorded so far from Myanmar (SI1). Of those, 145 belong to the order Anura (ca. 95%), five to the Caudata (ca. 3%), and two to the Gymnophiona (ca. 1%). They belong to 10 families (see Figure 2a) and 49 genera, with the genus Hylarana in the family Ranidae being the most species-rich in the country with 15 species.

3.2 Endemism

Of the 152 amphibian species occurring in Myanmar, 25 (16.4%) are endemic (see Table 1). 22 (88%) belong to the order Anura and three (12%) to the salamanders. No Gymnophiona extant in Myanmar is endemic to the country. The family with the most endemic species is Ranidae, with six frog species (24%), followed by the frog family Dicroglossidae with five endemic species (20%), and the frog family Rhacophoridae with four species (16%). After that, the three families, Bufonidae, Microhylidae, and the salamander family Salamandridae follow with three species (each 12%). The family with the least number of endemic species is the Megophryidae with one species (4%). Of the 25 endemic species, ten were classified as CE (40%), seven as RE (28%), and eight as ME (32%) (see Table 1).

| Species | IUCN status | Grade of endemism | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hylarana margariana | DD | CE | The eastern part of Shwegu township, west Bhamo, Kachin; generally Kachin |

| Amolops latopalmatus | NE | CE | Extreme southern Myanmar (Tanintharyi) |

| Amolops longimanus | DD | ME | Kambaiti Village, Kachin (2000 m asl) |

| Amolops marmoratus | LC | CE | Mon, Shan, Kayin, Kayah, Bago, Kachin, Mandalay, Tanintharyi |

| Ansonia kyaiktiyoensis | EN | ME | Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, Mon (1033 m asl) |

| Ansonia thinthinae | EN | RE | Me Kyauklonegyi Stream in Tanintharyi Nature Reserve |

| Duttaphrynus crocus | DD | RE | Two closely situated localities adjacent to Rakhine Yoma Elephant Sanctuary (Gwa Township, Rakhine) |

| Feihyla punctata | DD | CE | Gwa Township (Rakhine); Ngaputaw Township (Ayeyarwady) |

| Fejervarya kupitzi | NT | CE | Alaungdaw Kathapa National Park (Sagaing), Bago Yoma (Bago) |

| Hylarana oatesii | DD | CE | Bago, Yangon |

| Hylarana roberti | VU | CE | Dewei (Tanintharyi) |

| Kalophrynus anya | LC | CE | Chattin Wildlife Sanctuary (Sagaing); South-central Kachin |

| Leptobrachium rakhinense | EN | CE | Rakhine Hills (Rakhine, Bago) |

| Limnonectes bagoensis | NE | CE | Bago, Yangon |

| Limnonectes bagoyoma | NE | RE | Bago Yoma mountain range (Bago) |

| Microhyla fodiens | DD | ME | Kan Pauk (Yesagyo Township, Magway, 230 m asl) |

| Microhyla irrawaddy | DD | RE | Suburbs of Pakokku city on the bank of the Irrawaddy River (Pakokku, Magway); in the vicinity of Kan Pauk village (Yesagyo Township, Pakokku, Magway) |

| Nanorana feae | DD | RE | Kakhyen Hills (Kachin) |

| Occidozyga myanhessei | NE | RE | Dawei (Bago); East Yangon University, Mingalardon (Yangon) |

| Philautus cinerascens | DD | ME | Ataran River, east of Moulmein (Mon, Type locality) |

| Philautus tytthus | DD | ME | Htingnam (Kachin, Type locality) |

| Rhacophorus turpes | DD | ME | Htingnam (Kachin, Type locality) |

| Tylototriton kachinorum | DD | ME | Slopes of Ingyn Taung Mountain (Mohnyin Township, southern part of Kachin Hills, Kachin) |

| Tylototriton ngarsuensis | DD | ME | Baw Hto Chang in Ngar Su Village (Ywnagan Township, Taunggyi, Shan, 1212 m asl) |

| Tylototriton shanorum | VU | RE | Taunggyi, Kalaw, Pindaya, Nyaungshwe, Pinlaung townships (Shan) |

3.3 Threat status

Even though only seven (4.6%; Ansonia kyaiktiyonensis, Ansonia thinthinae, Hylarana roberti, Leptobrachium rakhinense, Nanorana yunnanensis, Oreolalax jingdongensis, Tylototriton shanorum) of the 152 amphibian species extant in Myanmar are classified as threatened, this number could be higher considering the 27.6% of species with insufficient available data. Counting those as potentially threatened increases Myanmar's threatened amphibian species to 49 (32.2%). Of those, 43 belong to the order Anura, four to the Caudata, and two to the Gymnophiona. The family with the most threatened species is Ranidae, with 13 species, then follow the families Dicroglossidae and Rhacophoridae, with eight species. For 22 (14.5%) of the 152 species occurring in Myanmar, the IUCN Red List threat status is older than 10 years (Figure 2b and Supporting Information S1: SI1).

Five of the seven species classified as threatened are endemic to Myanmar, and for over 65% of the endemic species, there is only insufficient information available. Considering those 17 species with insufficient data as potentially threatened, the number of threatened endemic species becomes as high as 22 (88% of all endemic species). The family with the most threatened endemic species is Ranidae, with five species, followed by Dicroglossidae and Rhacophoridae, with four species each. After that, follow the families Bufonidae and Salamandridae with three species and Microhylidae with two species. The family with the smallest number of threatened endemic species is Megophryidae, with one species. For two (8%) of the 25 species endemic to Myanmar, the IUCN Red List threat status is older than 10 years (see Figure 2b and SI1).

3.4 CITES

Six (3.9%) out of the 152 amphibian species in Myanmar are listed in the Appendices of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Out of those, only Hoplobatrachus tigerinus belongs to the order Anura. The other five species (Tylototriton kachinorum, T. ngarsuensis, T. panwaensis, T. shanorum, T. verrucosus) belong to the order Caudata. The six species are listed in Appendix II of CITES (CITES, 2023c). Half of the species are endemic to Myanmar; one is threatened, and three are potentially threatened.

3.5 Spatial analysis of species richness

Myanmar has 53 PAs, which cover 6.6% (44,289 km2) of the roughly 673,079 km2 land area, and 0.5% (2,457 km2) of the roughly 514,147 km2 marine and coastal area (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, 2023, see Figure 1b).

The number of amphibian species in Myanmar is generally high in the eastern part of the country along the Shan Plateau all the way down to peninsular Myanmar in the South, whereas on the western side towards the border to India and the coastal regions, there are rather fewer species. It is noticeable that in the far eastern and southern regions where the highest numbers of species are found, there is also a lack of larger PAs, as the biggest PAs are located in the North (Figure 1c).

Considering only species whose distribution is outside any PA the allocation is different. There is a peak in the far south of the country in the Tenasserim-South Thailand semi-evergreen rain forests in Tanintharyi, but elsewhere the number of species is relatively low. The only other minor peaks are in the northeast of Myanmar in southeast Kachin and northern Shan, as well as in the northwest of Myanmar in Sagaing and Chin on the border to India (Figure 1d).

3.6 Protected area coverage

Out of the 152 species occurring in Myanmar, the distribution area of 144 could be compared to the PAs of Myanmar. Our results suggest that 40 of the 144 species (27.8%) have a distribution area outside any PA. Out of those 40 species, two (Nanorana yunnanensis and Tylototriton shanorum) are threatened according to the IUCN (VU, EN, CR), and 15 are potentially threatened (IUCN status DD or NE). Of these 17 species, 12 are endemic to Myanmar. Hence, 28.6% of the threatened, 35.7% of the potentially threatened, and 48% of the endemic amphibian species in Myanmar are not protected through any PA (see Table 2 & Supporting Information S1: SI4).

| Species | IUCN status | Endemism status |

|---|---|---|

| Hylarana margariana | DD | CE |

| Amolops longimanus | DD | ME |

| Amolops panhai | LC | NoE |

| Amolops viridimaculatus | LC | NoE |

| Clinotarsus alticola | LC | NoE |

| Duttaphrynus crocus | DD | RE |

| Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis | LC | NoE |

| Hoplobatrachus litoralis | LC | NoE |

| Hylarana eschatia | LC | NoE |

| Hylarana malayana | NE | NoE |

| Hylarana oatesii | DD | CE |

| Hylarana tytleri | LC | NoE |

| Ingerana borealis | LC | NoE |

| Leptobrachium huashen | LC | NoE |

| Leptomantis cyanopunctatus | LC | NoE |

| Limnonectes bagoyoma | NE | RE |

| Microhyla mantheyi | LC | NoE |

| Nanorana feae | DD | RE |

| Nanorana yunnanensis | EN | NoE |

| Nyctixalus pictus | LC | NoE |

| Occidozyga myanhessei | NE | RE |

| Odorrana hosii | LC | NoE |

| Odorrana livida | DD | NoE |

| Orixalus carinensis | DD | NoE |

| Philautus cinerascens | DD | ME |

| Philautus tytthus | DD | ME |

| Polypedates discantus | NE | NoE |

| Polypedates megacephalus | LC | NoE |

| Polypedates teraiensis | LC | NoE |

| Pterorana khare | LC | NoE |

| Raorchestes andersoni | LC | NoE |

| Raorchestes longchuanensis | LC | NoE |

| Rhacophorus nigropalmatus | LC | NoE |

| Rhacophorus norhayatiae | LC | NoE |

| Rhacophorus turpes | DD | ME |

| Tylototriton ngarsuensis | DD | ME |

| Tylototriton shanorum | VU | RE |

| Tylototriton verrucosus | NT | NoE |

| Xenophrys glandulosa | LC | NoE |

| Zhangixalus dennysi | LC | NoE |

Twenty-three (16%) of the 144 species, whose distribution was compared to the PAs of Myanmar, are only covered by one PA. Three of those species (Ansonia kyaiktiyoensis, A. thinthinae, and Hylarana roberti) are considered threatened by the IUCN (VU, EN, CR), and eight are potentially threatened (NE or DD). Of those 11 species, six are endemic to Myanmar. There is one more endemic species on this list, that is classified as LC (Kalophrynus anya). Hence, 42.8% of the threatened, 19% of the potentially threatened, and 28% of the endemic amphibian species in Myanmar are only covered by one PA (see Table 3).

| Species | IUCN status | Endemism status | Protected area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amolops putaoensis | NE | NoE | Hponkanrazi Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Ansonia kyaiktiyoensis | EN | ME | Kyeikhtiyoe Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Ansonia thinthinae | EN | RE | Taninthayi Nature Reserve |

| Feihyla punctata | DD | CE | Rakhine Yoma Elephant Range |

| Hylarana humeralis | LC | NoE | Inkhain Bum National Park |

| Hylarana roberti | VU | RE | Taninthayi Nature Reserve |

| Ichthyophis multicolor | DD | NoE | Hlawga Park |

| Kalophrynus anya | LC | CE | Shwe-U-Daung Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Kaloula latidisca | DD | NoE | Lampi Marine National Park |

| Leptobrachium chapaense | LC | NoE | Shwe-U-Daung Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Limnonectes bagoensis | NE | CE | Hlawga Park |

| Limnonectes bannaensis | LC | NoE | Loimwe Protected Area |

| Limnonectes hascheanus | LC | NoE | Taninthayi Nature Reserve |

| Limnonectes kohchangae | LC | NoE | Taninthayi Nature Reserve |

| Micryletta lineata | LC | NoE | Taninthayi Nature Reserve |

| Nanorana arnoldi | DD | NoE | Hkakaborazi National Park |

| Nasutixalus jerdonii | LC | NoE | Hponkanrazi Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Odorrana macrotympana | DD | NoE | Htamanthi Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Rhacophorus verrucopus | NT | NoE | Htamanthi Wildlife Sanctuary |

| Sphaerotheca cf. breviceps | LC | NoE | Hlawga Park, |

| Tylototriton kachinorum | DD | ME | Hukaung Valley Wildlife Sanctuary (extension) |

| Zhangixalus burmanus | LC | NoE | Hkakaborazi National Park |

| Zhangixalus smaragdinus | LC | NoE | Taninthayi Nature Reserve |

3.7 ZIMS analysis

Of the 152 species occurring in Myanmar, 19 are held in zoos worldwide (12.5%). They almost all belong to the order Anura except Tylototriton verrucosus, which belongs to the Caudata. None of Myanmar's threatened or potentially threatened (DD, NE) species and none of the endemic species are kept in any zoo or aquarium worldwide (see Table 4 and Supporting Information S1: SI5).

| Species | IUCN status | Individuals | Hatchings | Total institutions (regions) | EAZA institutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duttaphrynus melanostictus | LC | 2026 | 270 | 24 (3) | 15 |

| Ingerophrynus parvus | LC | 11 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Phrynoidis asper | LC | 78 | 0 | 13 (2) | 3 |

| Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis | LC | 3 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hoplobatrachus tigerinus | LC | 3 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hylarana cubitalis | LC | 262 | 0 | 4 (1) | 4 |

| Hylarana erythraea | LC | 9 | 0 | 2 (1) | 2 |

| Hylarana nigrovittata | LC | 138 | 10 | 2 (1) | 2 |

| Occidozyga lima | LC | 72 | 0 | 2 (2) | 1 |

| Glyphoglossus guttulatus | LC | 1 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Kaloula pulchra | LC | 59 | 0 | 17 (5) | 7 |

| Microhyla butleri | LC | 8 | 0 | 2 (1) | 1 |

| Nyctixalus pictus | LC | 163 | 105 | 10 (2) | 5 |

| Polypedates leucomystax | LC | 193 | 0 | 12 (3) | 10 |

| Polypedates megacephalus | LC | 235 | 0 | 11 (1) | 10 |

| Rhacophorus kio | LC | 3 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Rhacophorus nigropalmatus | LC | 38 | 0 | 2 (1) | 2 |

| Theloderma asperum | LC | 32 | 0 | 5 (2) | 1 |

| Tylototriton verrucosus | NT | 133 | 35 | 15 (1) | 10 |

Concerning the One Plan Approach, all of the species which are currently kept are also found in other countries, so the individuals/populations are not necessarily descended from founder animals from Myanmar. Although they correspond to the same species, they should not be used for reintroduction in Myanmar. It is also important to mention again that this study only analyzed the ZIMS database. This database is not used by every zoo or aquarium, so some species may be kept somewhere else, e.g., there may be stations or other institutions in Myanmar that hold endangered or endemic species.

4 DISCUSSION

When compiling the species list of the amphibians in Myanmar, it became evident that for a number of species information on the distribution area is still scarce, and also the taxonomy of several species is unclear (Mulcahy et al., 2018). There are many species groups containing more than one species, and cryptic species associated with the country, and therefore, the number of amphibians occurring in Myanmar is certainly much higher than currently recognized.

That lack of information is also evident in the 16 species of this study not listed on the IUCN Red List, the 26 species only listed with insufficient data, and the 22 species whose last IUCN assessment was more than 10 years ago. With this total of 60 species, there is insufficient information on 39.5% of the amphibians in Myanmar. Considering that species with insufficient data are more likely to be threatened than those assessed adequately, this is particularly concerning (Bland et al., 2014, cited after Meredith et al., 2016). It could bring the number of threatened species in Myanmar from the officially classified seven to 67 species. This would correspond to roughly 43% of all amphibians in Myanmar. Furthermore, most of the endemic species in Myanmar (18 species, 72%) are not assessed adequately by the IUCN. This is all the more worrying because endemic species are inherently more threatened on their own due to their narrow habitat preferences and small distribution areas (Meredith et al., 2016; Sheridan & Stuart, 2018). Add to this fact that there is only insufficient information available about them, and the number of endangered endemic amphibian species in Myanmar could very likely include 23 species, not just the five species currently officially classified as threatened. That would correspond to 92% of the endemic species in Myanmar.

According to Luedtke et al. (2023), the overall proportion of amphibian species classified as DD on the IUCN Red List has decreased from 22.5% in 2004 to 11.3% in 2022. However, according to the results presented herein, this same proportion is still at 17.1% for Myanmar's amphibians, well above the average of 11.3%. Luedtke et al. explain the decline in this proportion for all amphibians in part by the fact that more information is available on amphibians compared to 2004. The fact that the figure for Myanmar's amphibians has remained high illustrates once again the lack of relevant knowledge about the species there and shows that Myanmar is not a high priority for herpetological research. Further studies on the amphibian species of Myanmar are necessary to assess which species actually occur in the country and which are threatened and need conservation actions. A lot more information is needed to be able to initiate appropriate protective measures should they be required.

The protective measures that already exist, for example, Myanmar's Conservation of Biodiversity and Protected Area Law of 2018 are not sufficient. The law has the objective to carry out the protection and conservation of wild fauna, wild flora, ecosystems and migratory animals. Therefore, the official list of protected species published in 2020 lists Myanmar's endangered species and categorizes them according to their degree of protection. However, Tylototriton verrucosus and T. shanorum are the only amphibian species represented on this list. Another example of insufficient protective measures for amphibians is the 53 PAs located throughout the country. It is noticeable in Figure 1c that most of the PAs in Myanmar are not located in the very species-rich areas in the east and south of the country. Those conservation gaps could stem from the fact that amphibians were not the focus of previous studies addressing the protection of Myanmar's nature (Mi et al., 2023; Zug, 2022). Thus, for future planning of PAs, amphibians should play a more significant role, and the focus should be mainly on the south of the country, as this is where most of the still unprotected species are located. Another reason for the lack of PAs in Myanmar's species-rich regions could be the fact that only 6.6% of the country's land area is covered by PAs anyways, which is not even half of the 15.1% protected land area average worldwide (Dinerstein et al., 2020; UNEP-WCMC and IUCN, 2023).

The lack of PAs can also be seen through the two (out of seven) threatened and 15 (out of 42) potentially threatened species with distributions outside of any PA. Out of those 17 species, 12 are also endemic to Myanmar. Further conservation measures should be considered for all these species to save them from extinction, with some of the species higher on the priority list as they are more vulnerable, like the species T. shanorum, as it is the only species threatened as well as endemic. However, other species like Hylarana margariana or Occidozyga myanhessei, who may only be considered possibly threatened should not be forgotten (see SI6).

The protection by one PA is sufficient for non-endemic species that are not threatened. Threatened and/or endemic species, on the other hand, need more protection, as PAs usually represent a static area that is limited in its ability to respond to external changes due to its insufficient dynamics and is therefore vulnerable to rapid environmental changes (D'Aloia et al., 2019). That is why, in this study, it was analyzed if any of the threatened, potentially threatened (again, here are only DD and NE species included, not species with an IUCN assessment older than 10 years), and endemic species, whom PAs cover, are only covered by a single one. This must be confirmed, as three (out of seven) threatened and eight (out of 42) potentially threatened species are only covered by one PA. Out of those 11 species, six are endemic to Myanmar. One more endemic species is covered only by one PA, which is not considered threatened. We suggest that all those species should be considered for further conservation actions, like for example ex situ protection, with the threatened species (Ansonia kyaiktiyoensis, A. thinthinae, and Hylarana roberti) at a higher level of priority, even though species like T. kachinorum, which is “only” possibly threatened but microendemic or the not threatened but endemic Kalophrynus anya should not be overlooked (see Supporting Information S1: SI6).

The analyses of this study demonstrate the large gaps still to be found in the protection of Myanmar's amphibians and the urgency behind taking further conservation action. It becomes clear how much the species suffer under the ongoing global amphibian crisis and yet are not the focus of attention when it comes to preserving the world's biomes, even though, with 41% of species threatened with extinction, they are the vertebrate group most at risk (IUCN, 2023). It should also be noted that the species whose last assessment by the IUCN was more than 10 years ago, but which are not classified as threatened (VU, EN, CR) or as DD or NE were not considered as potentially threatened in this study. Under the “worst case scenario”, these 18 species could also be threatened, adding to the list of species for which conservation action is needed. This could also be true for the eight species whose PA coverage could not be verified due to a lack of data regarding their distribution. Amolops latopalmatus, in particular, if not present in any PA, may require further protection measures as it is an endemic species. This shows once again that there is a knowledge gap for many amphibian species that needs to be addressed. Therefore, it is recommended to reevaluate all species whose last assessment by the IUCN was more than 10 years ago and study the distribution of the other species in greater detail.

Interpretation of our results needs to acknowledge data gaps and limitations. New species inventories may result in a better understanding of local amphibian diversity. This already becomes evident as some species lacking IUCN range data are listed in GBIF, which provides detailed coordinates of occurrences. Updating especially older IUCN assessments may hence result in a refined understanding of species distributions, likely enlarging ranges that might result in species being discovered in more PAs. On the other hand, ongoing habitat transformation may limit habitat availability and, ultimately also, ranges. Hence, the results of our spatial analyses provide a snapshot reflecting current knowledge, and they should be updated as soon as more data becomes available.

Another countermeasure that should be implemented is the mentioned conservation breeding, as none of the threatened, potentially threatened (again, here are only DD and NE species included, not species with an IUCN assessment, i.e., older than 10 years), or endemic amphibian species are being kept in any zoo or aquarium worldwide at the moment (at least none are recorded in ZIMS).

This is concerning because integrating ex situ and in situ protection, as stated in the One Plan Approach, may be “the only practical conservation option left for some species whose habitats are dwindling” (Schwartz et al., 2017, p. 2). Species that could fall into this category are Tylototriton shanorum, a threatened endemic species that is currently not protected by any PA, or Amolops longimanus, Philautus cinerascens, P. tytthus, Rhacophorus turpes, and Tylototriton ngarsuensis as they are microendemics considered as possibly threatened without protection through PAs. All those species could greatly benefit from ex-situ protection, and it would ensure that they do not become extinct while the planning of the protection of their habitats takes place. It would be beneficial if at least some of the holdings of the species were placed in facilities and stations in Myanmar itself, especially holdings of the country's endemic and endangered species. Some could already exist and are simply not recorded in the ZIMS database, which was used as the only means of verifying the species' holdings in this study.

5 CONCLUSION

This study serves as an overview of the situation of the amphibians in Myanmar and is intended to expand the work of Zug (2022) by analyzing and classifying amphibians specifically in terms of their threat status and conservation. The aim is to create an impetus to expand the protection of amphibians in Myanmar. Therefore, the results of this study have been compiled into a list containing the 36 amphibian species of Myanmar that are most in need of further protection and should, therefore, be prioritized in future conservation planning (Supporting Information S1: SI6). Also, this study has shown that there is still a significant gap in knowledge about Myanmar's amphibians, which should be addressed in future studies, and that although some conservation measures are already in place, especially Myanmar's threatened, and endemic amphibian species are still largely unprotected and thus at risk of extinction.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Marie Borgwerth: Writing—original draft; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software; visualization; data curation. Carolin Scholten: Writing—original draft; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software; visualization. Aung Lin: Writing—review and editing. Myint Kyaw Thura: Writing—review and editing. Larry Lee Grismer: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; writing—review and editing; resources. Thomas Ziegler: Conceptualization; investigation; writing—review and editing. project administration; resources; supervision. Dennis Rödder: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software; visualization; writing—review and editing; project administration; resources; supervision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Morris Flecks (Museum Koenig Bonn) for his valuable support in designing the figures and Ursula Bott (Museum Koenig Bonn) for technical assistance. This study is part of the BSc thesis of CS and MB without specific funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IUCN Red List (https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/grid) and the respective cited references. Data extracted from ZIMS are restricted to members only.