Innovative Exploration of Urban Nature Education: The Mini Botanical Garden Concept

城市自然教育的创新探索:小微植物园实践

Editor-in-Chief: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz | Handling Editor: Jin Chen

ABSTRACT

enMounting evidence reveals a growing disconnect between humans and nature, especially in densely populated urban areas. Despite many studies highlighting nature's vital role in human well-being, the opportunities and time for citizens to access quality natural spaces are diminishing, constrained by work schedules and urban environments. This study introduces the Mini Botanical Garden (MBG), a novel approach that involves the transformation of community green spaces aimed at enhancing urban residents' living environment and access to nature education, especially for children. Initially, a preliminary online survey was conducted to assess public satisfaction with existing community green spaces and gauge their acceptance of the MBG concept. Collaborating with local government departments and nature education institutions, we established four MBGs across communities in Ningbo city. Upon completion, various nature education programs targeting children were introduced in the gardens, including plant, insect, and bird identification, nature observation, handcrafts, and writing activities. To evaluate the effectiveness of the MBGs, 50 questionnaires were randomly distributed to local parent–child families. At present, all four completed MBGs feature both indoor nature education spaces and outdoor planting areas, showcasing over 100 plant species. The assessment results show that the MBGs have positively impacted the community environment and residents' lives, offering an easily accessible space for individuals—especially children—to reconnect with nature. In conclusion, the creation of MBGs offers a practical model for the popularization of urban nature education, addressing the growing issue of “nature-deficit disorder” caused by urbanization and promoting a harmonious relationship between humans and nature.

摘要

zh越来越多的证据表明, 人与自然之间日渐疏远, 特别是人口集中的城市地区。很多研究证实了自然在人类健康领域的重要作用, 但城市居民接触优质自然的机会和时间受工作和场地制约, 仍在不断减少。本文提出了一种新模式—小微植物园 (MBG), 它是对社区绿地的改造优化, 旨在为城市居民特别是儿童提供优质的生活环境和更多的自然教育资源。首先, 我们开展了一次网络调查, 以了解大众对于原有社区绿地的满意度, 及对社区内小微植物园落地的接受度。然后, 我们与宁波市的政府部门和自然教育机构合作, 在4个社区里建立了小微植物园, 并依托建成后的园区开展了丰富多彩的自然教育活动。此外, 为评估小微植物园的成效, 我们随机选择50个社区亲子家庭发放了调查问卷。截止目前, 已建成的4个小微植物园均包含室内自然教育场馆和室外种植区。其中, 室外种植区均展示超过100种植物。自然教育活动专为儿童设计, 涵盖植物、昆虫和鸟类识别、自然观察、手工制作和写作等主题。问卷结果显示, 小微植物园对社区环境和居民生活产生了积极影响, 为居民 (尤其是儿童) 提供了一个与大自然亲密接触的便捷空间。总之, 小微植物园的创建展现了重要的社会价值, 为普及城市自然教育提供了一个切实可行的参考模式, 有助于化解城市化进程中人的“自然缺失症”、促进人与自然和谐共生。

简明语言摘要

zh在人与自然渐行渐远的城市中, 社区绿地和自然教育被认为具有改善这种关系的潜在价值。在本研究中, 我们提出了一种名为 “小微植物园 (MBG)” 的新模式, 它可以为社区居民提供一个易到达易获取的自然空间。在政府部门和自然教育机构的帮助下, 我们在宁波市建立了四个小微植物园。每个园区都设有室外植物区和室内自然教育场馆。并且, 在这些小微植物园中, 为儿童设计了各种课程, 如动植物识别、自然观察笔记、手工制作和写作等。此外, 为了解社区家庭对小微植物园的态度, 我们进行了一次调查问卷。结果显示, 小微植物园对社区环境和居民生活产生了积极影响。所有家庭都认为, 小微植物园为社区居民 (尤其是儿童) 提供了一个亲近自然的场所。因此, 我们认为小微植物园是解决城市中人与自然疏远问题的一个值得推广的参考模式。

Summary

enIn cities, where people are becoming increasingly disconnected from nature, community green spaces and nature education have been recognized as effective ways to help people reconnect with the natural environment. In this study, we introduce the Mini Botanical Garden (MBG), a model that provides easily accessible natural spaces for community residents. With the support from the government and civil institutions, four MBGs were established in Ningbo city. Each MBG features outdoor plant areas and indoor nature education spaces. Various courses designed for children are offered at the MBGs, covering topics, such as plant and animal identification, nature observation, handcrafts, and writing. To gauge residents' attitudes toward the MBGs, questionnaires were distributed to families within the community. The results showed that the MBGs have positively impacted community environments and the lives of local residents, with all families agreeing that the MBGs provide a place for community members, especially children, to connect with nature. We believe the MBG model offers a practical solution to the problem of nature alienation in cities.

- ●

Practitioner Points

- ○

Community green spaces offer significant benefits for nature education. Urban planners and nature education organizations should create strategies to maximize their potential.

- ○

Establishing Mini Botanical Gardens (MBGs) is beneficial for the popularization of urban nature education. They provide a comfortable natural environment and rich natural experiences for local residents while also offering practical venues for various educational activities.

- ○

The maintenance and daily operation of MBGs require the collaborative efforts of management staff, botanical experts, educators, and community members. This ensures a shared platform for ongoing communication and engagement.

- ○

实践者要点

zh

-

社区绿地对自然教育普及大有裨益。城市规划者和自然教育组织应制定相关策略, 以更好地发挥其潜力。

-

建立小微植物园有利于普及城市自然教育。它们不仅能为当地居民提供舒适的生活环境和丰富的自然体验, 还能为各种教育活动提供便利的场地支持。

-

小微植物园的日常维护需要管理部门、专家学者、教育工作者和社区成员的共同参与, 这有助于建立一个可持续的共建、共享平台。

1 Introduction

An increasing number of studies indicate that proximity to nature benefits physical and mental well-being and boosts productivity and academic performance (Maddock and Johnson 2024; Fyfe-Johnson et al. 2021; Holland et al. 2021; Jeon et al. 2018). However, as urbanization accelerates, humans have become increasingly disconnected from the natural world in recent decades (Alvarez et al. 2022; Frumkin et al. 2017; Soga and Gaston 2016; Kahn and Kellert 2002). In the book Last Child in the Woods, American scholar Richard Louv (2008) coined the term “Nature-deficit disorder” to describe this phenomenon, while in his memoir The Thunder Tree, Pyle (1993) referred to it as the “extinction of experience.” This disconnection from nature can lead to an increased risk of health issues, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, depression, and anxiety (Frumkin et al. 2017; Louv 2008).

Nature education has emerged as one of the most powerful tools for establishing and strengthening emotional connections between humans and nature (Ives et al. 2018; Soga and Gaston 2016), helping individuals better interact with, learn from, and protect the environment. Ultimately, it encourages self-development and fosters a harmonious coexistence between humans and nature (Liu et al. 2023; Lin and Yong 2022; Li and Yu 2017; Uzun and Keles 2012).

Countries such as the United States, Japan, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, and the United Kingdom have long-established and refined nature education systems, with examples including the nature school models in the United States and Japan, the children's farm model in the Netherlands, the forest kindergarten model in Denmark and Germany, and the forest school model in the United Kingdom (Lin and Yong 2022; Yu and Qiu 2021; Zhang and Li 2019). These models provide great inspiration and valuable lessons for the development of nature education in China. Though nature education in the Chinese mainland started later, it has developed rapidly, especially since the early 21st century. Government agencies, experts, scholars, social organizations, and nonprofits are increasingly focusing on nature education, drawing on international experiences to explore and implement related activities (Lin and Yong 2022; Li and Yu 2017). A large number of national parks, nature reserves, botanical gardens, and urban parks are actively exploring and expanding their roles in nature education (Zhao 2023). By 2023, the number of organizations engaged in nature education in China had reached 21,556 (Huang 2024).

Natural venues are central to nature education, providing essential spaces for direct interaction with nature. In urban areas, where over half of the global population resides (United Nations 2019), green spaces are widely recognized for their physical and mental health benefits (Gianfredi et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2019). These urban green spaces, including botanical gardens and parks, are well-suited for nature education. Community green spaces, such as parks and surrounding green areas, are particularly accessible due to their proximity to residential areas, making them popular among residents (Mwendwa and Giliba 2012; Haq 2011). However, community green spaces often face challenges that hinder their ability to effectively promote nature education when compared to more suitable natural venues, like, botanical gardens and national parks. These deficiencies, which include low biodiversity (Ling 2014), disorganized landscape design (Taylor and Hochuli 2015), and a lack of clear educational signage or structured nature education activities, need to be addressed as soon as possible.

In response to these challenges, we propose a new model—the Mini Botanical Garden (MBG)—inspired by scientific botanical gardens as defined by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (Ren et al. 2022; Jackson 1999). The MBG model aims to provide urban residents, particularly children, with easily accessible nature experiences, helping them to establish a long-term connection with the natural world. A key element of this model involves transforming community green spaces to fulfill the main functions of a botanical garden, such as biodiversity conservation, science education popularization, nature education, and other services. In this study, we assessed the effectiveness of MBGs through feedback from local residents. Our findings indicate that the establishment of MBGs has had a positive impact on the community's outdoor living environment and provides easily accessible nature experiences for children.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Survey I

Before launching the project, we collaborated with Phoenix New Media to conduct an online questionnaire survey about the MBGs. The target audience was all users of the mobile application Ifeng News. The main body of the questionnaire consisted of a number of closed-ended questions. The survey aimed to publicize the MBG concept, assess public acceptance, and provide reference points to guide the project's implementation.

2.2 Project Design and Construction

To assess the feasibility of MBGs, we partnered with government departments and nature education organizations to identify suitable communities in Ningbo, China. The project's functional zoning, landscape design, and planting design were based on the Standard for Design of Botanical Gardens (CJJ/T 300-2019) and the Code for the Design of Public Parks (GB 51192-2016). Construction was carried out by professional landscaping companies.

2.3 Exploration of Nature Education Activities

Following the completion of the MBGs, we worked with the surrounding communities and nature education organizations to develop nature experience and science popularization courses tailored to these gardens. The educational institutions were responsible for course development and delivery, while Ningbo botanical garden provided professional guidance, and community members helped with logistical support. Course topics were typically aligned with the gardens' seasonal features, such as cherry identification during cherry blossom season. The courses were designed for children within the community, as early exposure to natural environments fosters a positive attitude toward nature (Cagle 2018; Chawla 2009; Evans et al. 2007; Wells and Lekies 2006). Recruitment for the courses was conducted through community bulletin boards and WeChat groups, with a target of 15 families per session. Courses were held once a week, usually on weekends or during holidays. All courses included outdoor nature experiences, which can strengthen children's connection to the natural world (Chawla 2020; Clayton and Myers 2015), stimulate their interest in nature, and enhance learning (Liefländer et al. 2013).

2.4 Survey II

A follow-up questionnaire was conducted to preliminarily assess the impact of the MBGs and their activities on community residents and their children. The questionnaire included both close-ended and open-ended questions. Fifty questionnaires were randomly distributed to families with children in the Wan'an community, where one of the MBGs was located.

To ensure the reliability of the survey data, responses were filtered based on the time taken to complete the questionnaire and whether all questions were answered. Responses with a completion time under 1 min were excluded, as they were deemed potentially unreliable. Descriptive analysis was performed using frequencies and percentages to summarize the data. Copies of the original questionnaires are provided in the Supporting Information.

3 Results

3.1 Analysis of Survey I

After filtering, 234 valid responses were obtained. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 1. Among the participants, 202 respondents (86%) were aged between 26 and 60 years old, and 221 respondents (94%) held a university degree or higher, indirectly indicating the authenticity and reliability of the data.

| Survey item | Number (percentage) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | Under 18 years old | 6 (3) |

| 18–25 years old | 9 (4) | |

| 26–30 years old | 16 (7) | |

| 31–40 years old | 57 (24) | |

| 41–50 years old | 58 (25) | |

| 51–60 years old | 71 (30) | |

| Over 60 years old | 17 (7) | |

| Education level | Junior high school and below | 4 (2) |

| High school | 9 (4) | |

| University | 169 (72) | |

| Postgraduate and above | 52 (22) | |

| Satisfaction with current community greening | Satisfied | 152 (65) |

| Indifferent | 16 (7) | |

| Dissatisfied | 66 (28) | |

| Whether the MBG is worth promoting and exploring for community greening enhancement | Worthwhile | 194 (83) |

| Unsure | 40 (17) | |

| Housing purchase willingness toward communities with an MBG | Willing | 208 (89) |

| Indifferent | 26 (11) | |

| Willingness to contribute to the MBG transformation in the community | Willing | 234 (100) |

| Indifferent or unwilling | 0 (0) | |

- Abbreviation: MBG, Mini Botanical Garden.

Of the respondents, 66 (28%) expressed dissatisfaction with the greening of their current residential community, while 194 (83%) believed that the MBG concept was a promising direction for enhancing community greening. When asked about their willingness to purchase a house, 208 respondents (89%) indicated they would prefer to live in a community with an MBG. Additionally, all respondents expressed a willingness to contribute to the construction of MBGs within their communities. These results suggest that the MBG concept aligns with societal needs and resonates with a society focused on ecological sustainability.

3.2 Implementation of MBGs

As of today, all four MBGs have been completed and are actively in use. Key details are shown in Table 2. Each MBG includes indoor education spaces and outdoor planting areas, spanning over 1000 m2 and featuring more than 100 plant species.

| Project | Outdoor planting areas (m2) | Indoor education venues (m2) | Plant species | Composition of nature elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wan'an | > 1000 | 90 | > 100 | Sequential arrangement of bryophytes, ferns, gymnosperms, monocots, and dicotyledonous angiosperms forming a path of plant evolution. |

| Vanke-1 | > 5000 | 145 | > 300 | Thematic gardens of spring, summer, autumn, and winter; five-sense garden. |

| Vanke-2 | > 2500 | 160 | > 180 | Plum garden, rock garden, cherry garden, and aquatic woody plant garden. |

| Vanke-3 | > 3000 | 140 | > 200 | Aromatic plant garden, dry creek garden, plum garden, and 24 seasons plants. |

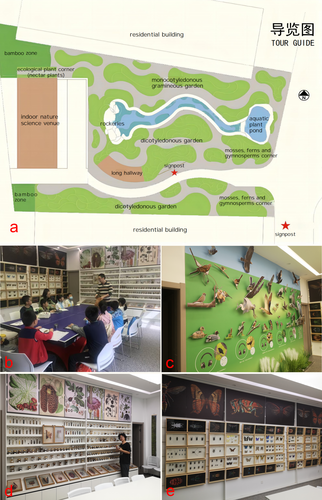

The Wan'an MBG was the first to be completed and launch educational activities. It involved the transformation and upgrading of existing community green space. The plant diversity in the outdoor planting area was greatly enhanced, with over 100 species of plants introduced and selected according to their growth characteristics and landscape requirements. Several mini specialized gardens were set up, including bryophyte, fern, and gymnosperm corners; a dicotyledonous garden; a monocotyledonous gramineous garden; a butterfly ecological plant corner (nectar plants); an aquatic plant pond; and a bamboo zone (Figure 1). The sequential arrangement of bryophytes, ferns, gymnosperms, monocots, and dicotyledonous angiosperms formed a path of plant evolution. Each plant species in the MBG was labeled with classification information, primarily for science popularization activities related to plants and for the use of community residents and plant enthusiasts.

The renovated indoor venue was transformed into a nature museum focused on birds, insects, and plants (Figure 1). The exhibits include a bird display wall showcasing 40 species of common birds in Ningbo, with Quick Response (QR) codes providing access to sounds, pictures, and text descriptions; an insect wall featuring 150 species from around the world, highlighting the most beautiful, largest, and most poisonous insects; and a seed wall displaying over 200 types of plant seeds, including those of medicinal herbs, grains, oils, rare species, timber, and spices. The seeds were categorized by different dispersal methods and fruit types. These elements serve as an introduction to natural science for children.

When collaborating with Vanke, we participated directly in the initial design stage of the green spaces as all three communities were newly built or still under construction. The outdoor planting area at Vanke-1 was much larger than the one at the Wan'an community and was divided into four themed gardens: spring, summer, autumn, and winter, featuring over 300 plant species. The five-sense garden in the summer thematic garden, covering an area of 180 m2, has been particularly popular. Children are able to experience more than 50 types of special plants through five dimensions: sight, smell, hearing, touch, and taste, hopefully sparking their curiosity about nature (Figure 2a). Each plant is labeled with its Chinese and scientific names, classification, and a QR code providing a voice introduction (Figure 2b). A number of insect houses have also been set up for children to observe (Figure 2c). The indoor nature experience venue is located next to the five-sense garden (Figure 2d).

3.3 Implementation of Nature Education Activities

Leveraging the easy accessibility and rich biodiversity of the MBGs, a number of diversified and systematic nature education courses were developed. These courses were organized into six categories: plant cognition, insect cognition, bird cognition, nature observation and note-taking, nature writing, and nature handcrafts. Taking advantage of the abundant plants and insect houses in the five-sense garden, plant identification and insect identification courses were offered. Most courses lasted 90 min, except for nature writing and nature handcraft courses, which lasted 120 min. The majority of children participating in the courses were primary school students or younger, typically under the age of 12.

During MBG activities, we emphasized direct observation and hands-on experiences to allow children to verify book knowledge and draw their own conclusions through their own observations of natural phenomena and interactive experiments (Figure 3). An example of the nature education courses offered in the MBG is shown in Table 3, which includes the course themes, objectives, and processes. In the “Poetry for Spring” course, most children were able to write about the spring they observed, either following a template or using free-form expression. With guidance, the children were able to relate aspects of their daily lives—such as food, clothing, and sound—to the plants or animals in the MBG, inspiring poetic phrases like “spring on the tip of the tongue and spring in the chirping of birds.”

| Item | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Activity theme | Poetry for spring | |

| Activity purpose | Guide children to observe spring in the MBG, learn about spring in ancient poems, and write their own poems. | |

| Activity process | Indoor introduction (20 min) | “What spring poems have you read?” Discuss spring using poems and engage children in a conversation about what they know, stimulating interest in the theme. |

| Outdoor nature observation (50 min) | Go outdoors to observe the spring features in the MBG, such as sprouting, blooming, or fruiting plants like magnolias and cherry, and traces of insects, like, beetles and moths. | |

| Indoor writing (30 min) | Guide children to write poems about spring they observed using the format “Where is spring, spring is ____.” | |

| Artwork showcase and summary (20 min) | Encourage children to share their poems and their experiences of spring. | |

- Abbreviation: MBG, Mini Botanical Garden.

Parents of participating children felt that poems derived from direct observation were more authentic and moving, suggesting that this approach should be used in children's writing education. Moreover, discovering real-life creatures during insect cognition, bird cognition, and nature observation activities brought immense joy to the children. Creatures commonly observed in the MBG include insects, like, praying mantises, katydids, damselflies, butterflies, and longhorn beetles, as well as birds, like, bulbuls, bead-necked doves, blackbirds, sparrows, and great tits. Some of the courses that have been popular with children are listed in Supporting Information Materials.

3.4 Findings of Survey II

Of the 50 questionnaires collected, 41 were valid. Table 4 summarizes the results of Survey II. In 37 (90%) of the families, at least one parent had received a higher education, with a college degree or above. The majority of children (40, or 98%) were under the age of 12. Additionally, 26 (63%) families were aware of and had visited the MBG and the indoor nature education venue. Among these, 10 (38%) had also participated in nature education activities within the MBGs. Families who were not familiar with the MBG expressed interest in learning more and hoped for more publicity from the community.

| Item | Number (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Age of the child | |

| Under 8 years old | 9 (22) |

| 8–12 years old | 31 (76) |

| Over 12 years old | 1 (2) |

| Education level of father or mother | |

| High school and below | 4 (10) |

| College and above | 37 (90) |

| Known and visited the MBG and indoor education venue | 26 (63) |

| Participated in activities within MBGs | 10 (38) |

| Gained something from activities | 9 (90) |

| Believed that the MBG played an active role for community residents | 41 (100) |

| Willingness to become a member of the MBG volunteer team | 41 (100) |

| Favorite courses | |

| Plant cognition courses | 38 (93) |

| Insect cognition courses | 35 (85) |

| Bird cognition courses | 35 (85) |

| Nature observation and noting courses | 34 (83) |

| Nature handcraft courses | 23 (56) |

| Nature writing courses | 20 (49) |

- Abbreviation: MBG, Mini Botanical Garden.

Of the families who had participated in activities, 9 (90%) reported that they gained valuable knowledge, learning more about animals and plants, getting closer to nature, and improving social skills. Furthermore, 7 (70%) families felt that the MBG activities were more relevant to everyday life, more accessible given their close proximity, and more convenient to participate in compared to similar activities offered elsewhere.

All participating families agreed that the MBG provides a valuable space for community residents, especially children, to get close to nature and explore its wonders. The MBG was seen as having a positive impact on the community environment and residents' lives, enhancing the overall esthetics of the community, encouraging more outdoor activities, and deepening residents' understanding and appreciation of nature. Families also expressed their willingness to join the MBG volunteer team and actively participate in future activities.

Survey results regarding the six types of courses already offered showed the following popularity ranking: plant cognition courses > insect cognition courses > bird cognition courses > nature observation and note-taking courses > nature handcraft courses > nature writing courses. This ranking will serve as an important reference for our subsequent event planning, publicity, and distribution strategies.

4 Discussion

Seppelt and Cumming (2016) argued that humans must reduce the cognitive distance from nature while increasing the distance of direct human impact on ecosystems to maintain Earth's life support systems. The MBG concept epitomizes this harmonious equilibrium, not only providing community residents with more opportunities to connect with nature, but also circumventing the potential for excessive anthropogenic interference that might imperil the integrity of pristine ecosystems. The main advantage of the current MBG model is that they are easily accessible and do not jeopardize the natural environment. While landscaping and biodiversity in the MBGs are enhanced, maintenance demands have increased compared to traditional community green spaces. With upgraded resources, the activities carried out have become more diverse, but the format has not seen significant innovation. These realities remind us of the need for further development and refinement of the MBG concept.

For the four completed MBGs, the outdoor planting areas and indoor education venues are the core components. As part of the outdoor green spaces, the planting areas provide habitats for plants, insects, and birds, while also offering a comfortable recreational environment for community residents (Reyes-Riveros et al. 2021). Additionally, they serve as quality biological resources and venues for nature activities, such as plant and insect identification (Mensah et al. 2016). Specialized gardens within the planting areas provide opportunities to explore various aspects of nature, such as using “the path of plant evolution” to learn about plant development or observing the blooming process of water lilies in the aquatic plant area. The selection of over 100 plant species, which are rich in diversity, enhances both the educational value and the beauty of the gardens. Therefore, the design of these outdoor planting areas should prioritize esthetic appeal and species richness, creating specialized gardens that promote ecological awareness and nature education. The selection of plant species should balance beauty, ease of survival, and availability.

The indoor education venues serve as multifunction classrooms, providing access to equipment and tools for teaching activities (Lu et al. 2015). They also function as museums, showcasing natural specimens for residents to enjoy (Alberti 2005). The combination of these two core components provides a comprehensive foundation for nature education in the MBGs.

In Survey II, some respondents expressed a desire to learn more about the MBGs and to participate in more activities, suggesting that the promotion and publicity of the MBGs and their programs in the communities were still insufficient. There is a need for more active guidance to engage additional residents. Furthermore, with the increase in plant species and the transplantation of nonnative plants, the existing community gardeners are stretched beyond their capacity. Addressing these challenges has become a top priority. Stukas et al. (2016) noted that volunteering is beneficial to both the community and the volunteers themselves, and that the volunteers are more motivated when the work aligns with their own interests. Gibson et al. (2024) mentioned that engaging community members who are not typically involved in community activities but have an interest in gardening or research can help broaden the diversity of the volunteer team. Providing volunteers with specialized skills training can also help them perform their tasks more efficiently (Dempsey-Brench and Shantz 2022). Therefore, recruiting volunteers and offering them professional training may be a practical solution to address the immediate challenges, particularly with regard to tasks like plant maintenance, guiding activities, and interpretation, which would greatly reduce the pressure on community managers.

In the past, the organization and development of activities were mostly undertaken by educators, with residents acting as passive participants. However, children and adults can also play a role in planning and innovating nature education activities (Yu and Qiu 2021). Encouraging community residents to participate in the planning and implementation of MBG activities helps foster their initiative and also serves as a form of innovation, expanding the influence of the MBGs. For example, community members with special skills, such as flower arranging, plant painting, or bamboo weaving, could be invited to teach at the indoor education venue. Similarly, children in the community could share interesting natural phenomena they observe in their surroundings, further enhancing engagement with the community.

Reflecting on our progress, we believe that the creation of the MBGs provides a universal public service that contributes to the development of ecological civilization and fosters a new generation of citizens with green literacy. We aspire for every child in the city to experience nature and receive quality nature education in an MBG in their community. Moving forward, we are committed to popularizing the MBG model in cities across China, establishing a network of MBGs covering all urban communities, and making nature education accessible and beneficial to all urban residents.

5 Conclusion

Urbanization has contributed to a growing “nature-deficit disorder,” which poses a threat to children's health and the sustainable development of humanity. This study introduces the MBG as an innovative solution, blending the functions of botanical gardens with community green spaces to popularize nature education in urban settings. The goal is to help city dwellers, especially children, establish long-term connections with nature, encouraging a lifelong relationship with the natural world. As a readily accessible nature space, the MBG practice improves the nature experiences of community residents, contributes to the popularization of urban nature education, and offers a promising way to address “nature-deficit disorder.” Looking ahead, expanding the MBG model nationwide and establishing a network of MBGs across cities will further advance nature education and contribute to the growth of ecological civilization.

Author Contributions

Aoqi Zhang: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Yue Chen: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing – review and editing. Yong Hu: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing – review and editing. Wenjun Luo: funding acquisition, project administration, resources, writing – review and editing. Yaling Wu: investigation, project administration. Shuang Liu: conceptualization, investigation. Kaiyuan Wan: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge high gratitude to Prof. Jin Chen and Prof. Xiupeng Li for providing guidance on this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.