A Framework of Nature Education

自然教育的框架

Editor-in-Chief: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz; Handling Editor: Sifan Hu

ABSTRACT

enThis article presents a framework of nature education principles designed to support the professional growth of nature educators. Created by Cornell University's Civic Ecology Lab, the framework is based on an unstructured literature review. This framework has been applied and refined through the Nature Education global online courses, taken by over 2000 educators and other participants in 2021–2023. Course discussions and additional literature informed revisions to the framework, which now covers the foundational concepts, engagement approaches, and desired outcomes for nature education programs. University professors and educator trainers can use this framework to design relevant lectures, case studies, and other learning materials in their nature education courses and workshops intended for aspiring and current nature educators. Practicing nature educators can use this framework to evaluate and enhance their existing programs. This adaptable framework encourages further critique and modifications, and invites future research that will further define and conceptualize the field of nature education.

摘要

zh本文介绍了一个自然教育原则框架, 旨在支持自然教育工作者的职业发展。该框架由康奈尔大学公民生态学实验室创建, 以非结构化的文献综述为基础。在2021–2023年由2000多名教育工作者和其他学员所参加的《自然教育》全球在线课程中, 该框架获得了应用和完善。课程讨论和其他文献为修订该框架提供了资料, 使当前的框架涵盖了自然教育课程项目的基本概念、参与方法和期望成果。大学教授和教育工作者培训师可在其自然教育课程和面向有志从事自然教育工作和当前从事自然教育工作的人员举办的研讨会中, 利用该框架来设计相关讲座、案例研究和其他学习材料。自然教育从业者可利用该框架来评估和改进其现有的课程项目。该框架具有广泛适用性, 愿意进一步的批评和修改意见, 并欢迎未来开展相关研究, 以进一步定义自然教育领域并使其概念化。

Plain Language Summary

enNature education helps people develop a deeper connection with nature, fostering appreciation and stewardship of the environment. This article introduces a framework of nature education principles to support educators in designing and enhancing learning experiences. Developed through literature review and refined in Cornell University's global online courses, the framework includes foundational concepts (such as equity and multiple ways of knowing), engagement strategies (such as nature play and inquiry-based learning), and desired outcomes (such as nature connection and ecological integrity). Educators can apply this framework to update curricula, assess programs, and create meaningful nature-based learning opportunities. By strengthening human–nature relationships, nature education advances both human well-being and ecological sustainability.

科普摘要

zh自然教育帮助人们与自然建立更深层次的联系, 从而促进对环境的重视和管理。本文介绍了一个自然教育原则框架, 旨在支持教育工作者设计和提升学习体验。该框架在文献综述的基础上开发, 并在康奈尔大学的全球在线课程中得到完善, 涵盖了基本概念 (如公平和多种认知途径) 、参与策略 (如自然游戏和探究式学习) 和期望成果 (如自然联系和生态完整性) 。教育工作者可利用该框架来更新课程体系、评估课程项目, 并创造有意义的基于自然的学习机会。自然教育通过加强人类与自然的关系, 促进人类福祉和生态可持续性。

Summary

enThis article presents a conceptual framework of twelve nature education principles derived from nature education literature and practice. These principles are organized into three categories: foundational ideas (e.g., equity, multiple ways of knowing), engagement strategies (e.g., nature play, inquiry-based learning), and outcomes (e.g., nature connection, ecological integrity). This framework serves as a guide for the professional development of nature educators by helping them familiarize themselves with the concepts shaping this field. By aligning these principles with historical and contemporary environmental thought, the article highlights the critical role of nature education in promoting human well-being, addressing current environmental crises, and fostering a reciprocal relationship between people and the natural world.

- ●

Practitioner Points

- ○

Educators can apply the proposed nature education framework to design, refine, and evaluate their programs.

- ○

The framework helps curriculum developers ensure that nature education programs and activities incorporate three key areas: foundational ideas, engagement strategies, and desired outcomes.

- ○

The framework is adaptable, allowing its principles to be updated to reflect different educational settings, cultural contexts, and local ecosystems.

- ○

实践要点

zh

-

教育工作者可利用本文提出的自然教育框架来设计、改进和评估其课程项目。

-

该框架可帮助课程体系开发人员确保自然教育课程项目和活动中包含三大关键领域:基本概念、参与策略和期望成果。

-

该框架具有广泛适用性, 可根据不同的教育情境、文化背景和当地生态系统更新其原则。

1 Introduction

The relationship between people and nature is essential to the well-being of both society and the Earth systems. Nature education includes a wide range of programs, learning objectives, and teaching methods. Organizations such as nature centers, museums, botanical gardens, nature reserves, and schools involve people in nature-focused activities intended to foster a deeper appreciation of ecosystems and promote environmental stewardship. Participants may engage in activities such as hiking on nature trails, collecting scientific data, school gardening, shoreline cleanups, or simply enjoying time outdoors. Despite the variety of nature education programs, they all share a common goal: to cultivate a meaningful bond between people and nature, and to help society become more compatible with the biosphere through learning, stewardship, restoration, and civic engagement.

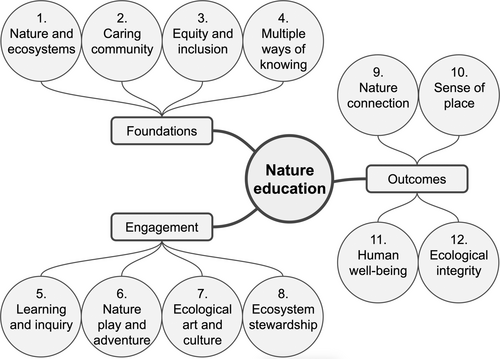

Nature education is still an emerging field of practice without a universally accepted definition or boundaries. Yet educator professional development requires at least a preliminary conceptual framework to help educators engage with the broad literature related to nature education. An example of educator professional development in this area is Cornell University's “Nature Education” global online courses. In this 4-week course, educators discuss relevant case studies, explore useful concepts such as nature connection and sense of place, and apply new ideas to their own nature education by creating or updating their curricula and activities. To create a cohesive learning environment in this course, a framework of nature education was developed through an unstructured literature review, akin to snowball sampling. This nature education framework combines several principles that give shape to nature education practice that can be discussed, modified, and applied by nature educators (Figure 1).

This framework has been used to develop materials and discussions in the Nature Education online courses offered three times in 2021–2023. Over 2000 participants, including teachers, nonformal educators, and university students have taken these courses, each time providing narratives and anecdotes from their programs, which led to minor revisions in this framework to reflect not only the literature but also the topics educators were interested in. In its current state, the framework's principles are divided into three categories: foundations, engagement, and outcomes. Foundations reflect program settings, such as local ecosystems, and values, such as a commitment to equity and inclusion. Engagement strategies capture diverse teaching and learning approaches, community involvement, and collaborative stewardship practices. Finally, desired outcomes include any results of nature education programs that can be measured or observed among participants, communities, or ecosystems.

Based on a broad body of literature, this framework is still emerging and tentative. While its principles reflect common themes and practices of nature education, this framework can help university professors and workshop instructors design professional development activities for nature educators. In addition, nature educators can use these principles to reflect on and refine their existing programs. Finally, this framework can inspire hypothesis-making, future systematic literature reviews, and empirical studies that will further advance nature education. Next, we will explore each principle for the current framework of nature education.

2 Nature Education Foundations

- (1)

Nature and ecosystems: Nature, including ecosystems, landscapes, and species, is central to nature education. The settings of nature education programs vary widely, from wilderness areas offering freedom of exploration (Haluza-DeLay 1999), to single trees used for climbing (Chawla 2007), and to green rooftops, linear parks, botanical gardens, and nature centers that bring nature into cities (Beatley 2011). Educators teach about nature in both rural and urban environments, often through specific lenses such as ecological corridors that connect habitats (Hilty and Worboys 2020), biodiversity threats driving a new wave of extinction (Kolbert 2014), regenerative cultures that support ecosystem restoration (Wahl 2016), and deep ecology emphasizing nature's intrinsic value (Drengson and Devall 2008).

- (2)

Caring community: Nature educators create welcoming spaces for children and families to explore nature and strengthen social bonds. They establish cultural expectations around nature-based activities and facilitate social learning among participants who learn about and care for nature (Chawla 2009). People from diverse backgrounds and generations come together through culturally relevant, nature-based activities, often involving recreation, sports, games, or wildlife observation (Price 2024). These programs cultivate communities of practice and shared nature-based experiences, helping participants develop stronger social capital, support one another, and contribute to local ecosystem improvement.

- (3)

Equity and inclusion: Nature education strives to eliminate barriers to learning about and experiencing nature, aligning with principles of equitable and inclusive education (Lawrence-Brown and Sapon-Shevin 2015). Factors such as low income, cognitive and physical abilities, lack of role models, low expectations, and structural injustices can exclude people from nature-based activities (Waite et al. 2023). Educators promote equity and inclusion by using trauma-informed approaches (Evans 2023; Hernández 2023), making programs more accessible, and addressing the historical roots of marginalization (Aguilar et al. 2017).

- (4)

Multiple ways of knowing: Nature education embraces various ways of engaging with nature beyond a science-focused approach, incorporating diverse cultural perspectives and knowledge systems. Participants are encouraged to bring their cultural heritage and lived experiences into their interactions with nature and their learning community. Educators also advocate for learning from traditional ecological knowledge of local and indigenous people (Kimmerer 2012), queer and emancipatory ideas (Gough et al. 2024), and the recognition of animal and nature rights (Kopnina and Cherniak 2015).

3 Nature Education Engagement

- (5)

Learning and inquiry: Outdoor and indoor nature education activities, often aligned with science learning standards, can support learning through unstructured exploration and formal inquiry. Nature interpretation, where guides share scientific facts and stories about natural phenomena, facilitates outdoor exploration (Zimmerman et al. 2006). To engage in interdisciplinary learning, systematic observation, and deep reflection, students can practice nature journaling (Arbor and Matteson 2024). They can also contribute to research through inquiry and citizen science projects, such as tracking bird migrations and conducting plant diversity surveys (Dickinson and Bonney 2012; Shirk et al. 2012). In addition, educators can involve people in community science, which emphasizes exploration driven by community needs, local knowledge, and a commitment to stewardship (Charles and Loucks 2020).

- (6)

Nature play and adventure: Unstructured play in nature supports positive child development (Taylor and Kuo 2009), and fosters strong social relationships (Dowdell et al. 2011). However, urbanization, technology, parental concerns, and narrow educational priorities often limit children's time in nature (Louv 2008). Despite these challenges, adventure education, outdoor recreation, camping, as well as forest and nature schools are gaining popularity among children and adults (Harper and Obee 2021). These activities promote outcomes such as self-confidence, social competence, and leadership (McLeod and Allen-Craig 2007), comfort in outdoor settings, and a sense of awe (Gilbertson et al. 2022).

- (7)

Ecological art and culture: Creating and exploring art related to nature, ecology, and the environment helps people appreciate the beauty and fragility of the natural environment (Thornes 2008). As a means of expression, introspection, and communication, various forms of art and culture—such as drawings, photography, designed landscapes, performance, exhibits, collections, and narratives—convey stories, emotions, possibilities, and values, shaping experiences and identities (Dutton 2006). Educators use ecological art to foster intellectual development and raise awareness about nature and environmental issues (Song 2012).

- (8)

Ecosystem stewardship: Engaging in ecosystem stewardship allows people of all ages to learn about and care for nature, including by designing nature-based solutions (Beatley 2011) and rewilding damaged habitats (Martin 2022). Activities like community gardening (Krasny and Tidball 2012), beach cleanups (Jorgensen et al. 2021), and mangrove restoration (Woon 2023) connect participants to nature and help them contribute to tangible restoration efforts. Effective stewardship relies on conservation policies and public support of nature protection (Bennett et al. 2018; Chapin et al. 2022), which can be enhanced by nature education programs. If ecosystem stewardship is sustained by participants beyond the duration of nature education programs, it can be viewed as an outcome of these programs.

4 Nature Education Outcomes

- (9)

Nature connection: Nature education aims to foster participants' nature connection, which is rooted in humans' intrinsic need to belong to the natural world (Wilson 1984; Kellert and Wilson 1993), and reflects how individuals understand, appreciate, identify with, engage with, and steward natural landscapes (Salazar et al. 2020; Krasny 2020; Couceiro et al. 2023). Strengthening nature connection brings people closer to ecosystems, increases their interest in outdoor activities, and forges a sense of responsibility for ecosystem stewardship. In addition, nature education aims to foster closely related concepts such as ecological identity, which reflects one's self-view in relation to nature, ecological processes, and the Earth (Thomashow 1996). Because people tend to enact their identities that are important and salient to them (Eccles 2009), nurturing identities that include nature and ecological values can improve an individual's environmental cognition and behavior (Walton and Jones 2018). Further, educators can foster students' interest in nature, one's desire to be captivated by nature, which may facilitate proenvironmental behaviors (Neurohr et al. 2024).

- (10)

Sense of place: Nature education can also influence one's sense of place, including place attachment, which is the bond between people and places, and place meaning, which is the symbolic significance or meanings ascribed to a location (Stedman 2002). An important aspect of the sense of place is “ecological place meaning,” which shows how ecosystems and nature-based activities become integral symbols of a place for individuals, influencing their proenvironmental behaviors (Kudryavtsev et al. 2012). Educators shape participants' sense of place, for example, through place-based education that grounds learning in the local community and environment (Sobel 2005), by incorporating nature-related artwork, storytelling, and writing storybooks (Jamal et al. 2024), as well as through social learning with peers and role models (Russ et al. 2015).

- (11)

Human well-being: Contact with nature offers numerous benefits to humans, including improved physical health, enhanced mood, strengthened social connections, and child development (Russell et al. 2013; Sia et al. 2020). Nature exposure promotes focused attention, physical exercise, and autonomy, which are key components of well-being (Capaldi et al. 2015). After recognizing these benefits, some healthcare providers have started prescribing nature-based activities—such as hiking, nature meditation, animal-assisted therapy, and horticulture programs—to patients for their physical and mental health (Kondo et al. 2020; La Puma 2019). In addition, the growing demand for nature-based well-being experiences is fueling the expansion of businesses and job opportunities, including outdoor yoga and wellness clubs (Price 2024, see at 11:45), ecotourism ventures (Skanavis et al. 2004), and campgrounds (Wang et al. 2016).

- (12)

Ecological integrity: While human activity has transgressed several planetary boundaries, threatening biosphere stability (Richardson et al. 2023), nature education aims to mitigate these impacts through ecosystem restoration and fostering societal transformation. Education programs involving habitat restoration report measurable ecosystem improvements (Ardoin et al. 2020). Beyond direct restoration, nature education can drive transformative changes in culture, social norms, government policies, economic systems, and civic engagement, enabling human society to coexist with thriving ecosystems. For example, educators and participants of nature education programs can advocate for biophilic urban zoning (Beatley 2011), mobilize support for large-scale land conservation (Wilson 2016), petition against excessive plastic use polluting ecosystems (Jorgensen et al. 2021), and contribute to establishing legal frameworks and cultural practices that recognize ecosystem personhood (Łaszewska-Hellriegel 2023).

5 Perspectives

This framework of nature education is rooted in the history of several overlapping branches of education—including nature study, conservation education, environmental education, outdoor education, place-based education, and sustainability education. Over a century ago, Cornell University professors Bailey (1911) and Comstock (1911) responded to the growing disconnection from nature among children and adults by developing nature study to foster scientific knowledge and esthetic appreciation of the natural world. These ideas are still present in contemporary practices of nature-based recreation, inquiry, and citizen science. Later, scholars and educators began to focus more on promoting a respectful relationship with ecosystems (Leopold 1949), which led to the introduction of conservation education in schools (American Association of School Administration 1951; Dambach and Finlay 1961). A similar emphasis on ecosystem conservation is evident in today's nature education programs and the proposed framework.

Further, the alarming scale of ecological degradation, combined with prominent environmental movements and a growing interest in interdisciplinary learning, led to the establishment of environmental education, whose goal is to enable people to solve complex environmental issues (Stapp 1969; Dillon and Herman 2023). Some consider that environmental education encompasses or greatly overlaps with nature education because both areas draw from a broad range of disciplines and teaching approaches. In addition, nature education borrowed ideas from outdoor education, which emphasizes the importance of outdoor play, outdoor skills, and the development of empathy towards living things (Martin 2004; Louv 2008), place-based education, which calls for engaging students with local communities and ecosystems (Sobel 2005), and sustainability education, which underscores that the health of natural systems is interlinked with human well-being, social equity, and economic prosperity (Marouli 2021).

While a broadly accepted definition of nature education has not yet been established, we observe that it is based on an assumption that spending time in nature and learning about nature contributes to human well-being and appreciation of nature in the short term, and to the protection of species, ecosystems, and the biosphere through changes in behavior, policies, and institutions in the long term. The proposed framework of nature education reflects these assumptions, the educational traditions mentioned above, and the reviewed literature.

This framework of nature education will continue to evolve in response to climate change, ecosystem degradation, and urbanization, as well as advancing ecological knowledge, and shifting ethical perspectives. For example, the “ecological integrity” principle becomes increasingly significant as the biosphere suffers severe damage (Richardson et al. 2023), many species are pushed towards extinction (Kolbert 2014), and climate change threatens the health of ecosystems (Malhi et al. 2020). In addition, environmental ethics increasingly calls for the protection of animal rights (Singer 1975), the advocacy for rights of nature (Gilbert et al. 2023), the recognition of intrinsic values in both humans and non-humans (Brennan and Lo 2021), and the promotion of people–nature reciprocity (Ojeda et al. 2022). By embracing such evolving social and environmental perspectives, educators and scholars will continue to shape nature education to enhance human well-being, foster ecological stewardship, and strengthen the human–nature relationship.

6 Conclusion

The nature education principles presented in this article were initially developed as an open-ended and flexible framework to guide educator professional development. This framework proved effective in structuring Cornell University's “Nature Education” online course, and was gradually modified in 2021–2023 to incorporate ideas that course participants express interest in. However, the goal of researchers is not only to synthesize mainstream literature and established practices of nature education, but also to help nature education introduce new topics and educational approaches that reflect emerging discourses in ecological restoration, policy-making, and ethics. Thus, the presented framework offers only an initial collection of nature education principles; it is open to development, critique, and adaptation to specific educational contexts. Finally, this framework paves the way for future literature reviews and empirical studies that will further advance the field of nature education.

Chinese Language Summary

本研究提出一个包含十二条自然教育原则的概念框架, 这些原则源自自然教育的文献和实践。该框架将这些原则归纳为三个类别:基础理念 (如:公平、多元知识体系) 、参与策略 (如:自然游戏、探究式学习) 以及预期成果 (如:自然联结、生态完整性) 。这一框架可作为自然教育者职业发展的指南, 帮助他们熟悉塑造该领域的核心概念。通过将这些原则与历史上和当代的环境思想相结合, 本文强调了自然教育在促进人类福祉、应对当前环境危机以及培育人与自然之间的互惠关系方面的重要作用。

Author Contributions

Alex Kudryavtsev reviewed the literature, developed the framework, and wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

The development of the Nature Education online course, which led to the creation of the nature education framework presented in this article, was generously supported by the Alibaba Foundation. Gratitude is extended to Dr. Marianne Krasny and Dr. Yue Li for providing useful feedback for the course lectures, which influenced the initial version of nature education principles discussed in this article. The author also thanks the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The author has nothing to report.