Free-ranging dogs and their owners: Evaluating demographics, husbandry practices and local attitudes towards canine management and dog–wildlife conflict

自由放养的家犬及其主人: 评估数量、饲养方法以及当地人对家犬管理和犬与野生动物冲突的态度

Editor-in-Chief & Handing Editor: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz

Abstract

enDomestic dogs, numbering over 900 million worldwide, are commonly kept as service animals and companions. However, their interactions with wildlife have become a growing concern for conservation biologists studying human–wildlife conflicts. It has been reported that domestic dogs pose threats to at least 188 wildlife species, a figure that is likely underestimated. In regions like Southeast Asia, the actual impact could be up to five times the current estimates suggest. This study was designed to explore community perspectives on dog–wildlife conflict within protected areas in rural Thailand, focusing on dog husbandry and promoting effective population management strategies. To gather data on dog ownership, management practices and community perspectives on dog–wildlife conflicts, a structured questionnaire survey was conducted amongst households in settlements surrounding protected areas in Northern Thailand. The survey revealed a widespread presence of domestic dogs in rural Thailand, with half of all households owning dogs and over 40% of these dogs having unrestricted movements. Despite this high prevalence, the impacts of dog–wildlife conflicts were not widely recognised by respondents in the study area. Respondents agreed that dog owners were responsible for controlling their own dogs, while local governments were responsible for controlling dog populations. The most popular management options for dog populations were nonlethal methods, including free vaccinations and sterilisation for owned dogs and trap-neuter-vaccinate-return programmes for strays. The lack of awareness among respondents about dog–wildlife conflicts highlights the need for educational activities on the impacts of free-ranging domestic dogs. Protected area managers must enforce dog-free policies within these zones to mitigate the potential threats to vulnerable wildlife populations. However, the lack of veterinary practices in the area represents a significant challenge to effective dog population management. Developing strategies to overcome this issue is crucial. Overall, the findings suggest that effective dog population management requires a collaborative approach between dog owners, local governments and conservation managers.

摘要

zh全球家犬数量超过 9 亿只,通常作为服务和伴侣动物饲养。然而,家犬与野生动物的相互作用已成为研究人类与野生动物冲突的保护生物学家日益关注的问题。据报道,家犬至少对 188 种野生动物构成威胁,且这个数字很可能被低估了。在东南亚等地区,实际影响可能是目前估计的五倍。本研究旨在探讨泰国农村保护区内家犬与野生动物冲突的社区观点,重点关注家犬的饲养和促进有效的数量管理策略。为了收集有关家犬的拥情况、管理方法以及社区对家犬与野生动物冲突看法的数据,我们对泰国北部保护区周边居民点的住户进行了结构化问卷调查。调查结果显示,家犬在泰国农村地区广泛存在,占一半的家庭拥有,其中40%以上的家犬活动不受限制。尽管这种现象非常普遍,但研究区域的受访者并未普遍认识到家犬与野生动物冲突的影响。受访者一致认为,主人有责任控制自己的犬只,而地方政府有责任控制家犬的数量。最受欢迎的数量管理方法是非致命性方法,包括为家犬提供免费疫苗接种和绝育服务,以及为流浪犬实施捕捉、绝育、疫苗接种和放归计划。受访者对家犬与野生动物冲突缺乏认识,这凸显了开展有关自由放养家犬影响的教育活动的必要性。保护区管理者必须在这些区域内执行无犬政策,以减轻对脆弱的野生动物种群的潜在威胁。然而,该地区缺乏兽医诊所,对有效管理家犬数量是一个重大挑战。制定策略以解决这一问题至关重要。总而言之,研究结果表明,有效的家犬数量管理需要犬主人、地方政府和保护管理者之间的协作。

บทคัดย่อ

thสุนัขมีการเลี้ยงกันอย่างแพร่หลายมากกว่า 900 ล้านตัวทั่วโลก เพื่อช่วยเหลือและเป็นเพื่อนกับมนุษย์ อย่างไรก็ตามปฏิสัมพันธ์ระหว่างสุนัขกับสัตว์ป่า สร้างความกังวลเพิ่มมากขึ้นให้แก่นักชีววิทยาการอนุรักษ์ที่ศึกษาปัญหาความขัดแย้งระหว่างมนุษย์กับสัตว์ป่า โดยมีรายงานว่าสุนัขคุกคามสัตว์ป่าอย่างน้อย 188 สายพันธุ์ และคาดว่าจำนวนที่ประเมินอาจจะต่ำกว่าความเป็นจริง ทั้งนี้เฉพาะในเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้เพียงแห่งเดียวจากการประมาณสูงกว่าที่ประเมินไว้ถึงห้าเท่า การศึกษานี้มีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อศึกษาทัศนคติของคนในชุมชนเกี่ยวกับความขัดแย้งระหว่างสุนัขและสัตว์ป่ารอบพื้นที่อนุรักษ์ตามชนบทประเทศไทย ได้แก่ การเลี้ยงดูและการส่งเสริมวิธีการจำกัดจำนวนสุนัขอย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ โดยใช้แบบสอบถามเชิงโครงสร้างในการศึกษา ซึ่งได้ดำเนินการสอบถามครัวเรือนที่ตั้งถิ่นฐานรอบพื้นที่อนุรักษ์ทางภาคเหนือของไทย เพื่อเก็บข้อมูลผู้เลี้ยงสุนัข แนวทางปฏิบัติในการจัดการ และทัศนคติของชุมชนเกี่ยวกับความขัดแย้งระหว่างสุนัขกับสัตว์ป่า จากผลการวิจัยพบว่าการเลี้ยงสุนัขเป็นที่แพร่หลายในชุมชนชนบทของไทย โดยครึ่งหนึ่งของครัวเรือนที่ทำการสำรวจทั้งหมดเป็นเจ้าของสุนัข และมากกว่า 40% ของสุนัขเหล่านั้นเลี้ยงแบบปล่อยอิสระไม่มีการควบคุม ถึงแม้ว่าจะมีการเลี้ยงสุนัขแพร่หลายมากในพื้นที่ศึกษา แต่ผลกระทบจากความขัดแย้งระหว่างสุนัขกับสัตว์ป่ายังไม่เป็นที่รับรู้มากนักของคนในชุมชน ผู้ตอบแบบสอบถามเห็นพ้องกันว่าเจ้าของสุนัขมีหน้าที่ควบคุมสุนัขของตัวเอง ในขณะที่หน่วยงานรัฐระดับท้องถิ่นมีหน้าที่ควบคุมจำนวนสุนัข ทั้งนี้แนวทางการจัดการที่ได้รับความนิยมมากที่สุดสำหรับควบคุมประชากรสุนัขคือวิธีการที่ไม่ทำให้ถึงตาย อย่างเช่น การฉีดวัคซีนและทำหมันสำหรับสุนัขที่มีเจ้าของ และการดักจับ-ทำหมัน-ฉีดวัคซีน-ปล่อยกลับสุนัขจรจัด การขาดความตระหนักเกี่ยวกับความขัดแย้งระหว่างสุนัขและสัตว์ป่าในกลุ่มผู้ตอบแบบสอบถาม แสดงให้เห็นถึงความสำคัญของการให้ความรู้เกี่ยวกับผลกระทบของของสุนัขเลี้ยงแบบปล่อยอิสระ เจ้าหน้าที่ที่ดูแลพื้นที่อนุรักษ์ต้องบังคับใช้นโยบายปลอดสุนัขในพื้นที่อนุรักษ์อย่างเข้มงวด เพื่อลดภัยคุกคามที่อาจเกิดขึ้นกับประชากรสัตว์ป่าที่เสี่ยงต่อการสูญพันธุ์ อย่างไรก็ตามการขาดแคลนสัตวแพทย์ปฏิบัติงานในพื้นที่ดังกล่าวถือเป็นอุปสรรคสำคัญต่อการจัดการประชากรสุนัขอย่างมีประสิทธิภาพ และสิ่งสำคัญอย่างยิ่งคือการพัฒนากลยุทธ์เพื่อแก้ปัญหานี้ สรุปผลการวิจัยนี้ชี้ให้เห็นว่าการจัดการประชากรสุนัขที่มีประสิทธิภาพต้องอาศัยความร่วมมือระหว่างเจ้าของสุนัข หน่วยงานรัฐท้องถิ่น และนักการจัดการอนุรักษ์

Plain language summary

enThis study explores the interactions between domestic dogs and wildlife in rural Thailand, focusing on protected areas. With over 900 million dogs worldwide, their impact on wildlife, threatening at least 188 species, has raised concerns. The study aims to understand community perspectives on dog–wildlife conflicts and promote effective population management methods. A survey was conducted in Northern Thailand, revealing widespread dog ownership, with 50% of households owning dogs and over 40% allowing unrestricted movement. Despite this, respondents did not widely recognise the impacts of dog–wildlife conflicts. The community suggested that dog owners should control their own pets while local governments should be responsible for managing dog populations. Preferred management options included nonlethal methods like free vaccinations and sterilisation for owned dogs and trap-neuter-vaccinate-return programmes for strays. The study highlights a lack of awareness about the impact of free-ranging dogs on wildlife, emphasising the need for education. Enforcing dog-free policies in protected areas is crucial, but the absence of veterinary practices poses a challenge. Effective dog population management requires collaboration between dog owners, local governments and conservation managers to address this complex issue.

通俗语言摘要

zh本研究以保护区为重点,探讨了泰国农村地区家犬与野生动物之间的相互作用。全世界有超过9亿只家犬,它们对野生动物造成影响,至少威胁到 188 个物种,受到广泛关注。这项研究旨在了解社区对家犬与野生动物冲突的看法,并推广有效的数量管理方法。在泰国北部进行的一项调查显示,家犬饲养现象非常普遍,占50%的家庭,其中40%以上的家庭允许犬只不受限制地活动。尽管如此,受访者并未普遍认识到家犬与野生动物冲突的影响。社区建议狗主人应管理好自己的宠物,而地方政府则应负责控制狗的数量。首选的管理方案包括非致命性方法,例如为养犬者提供免费的疫苗接种和绝育服务,以及为流浪犬实施抓捕、绝育、疫苗接种和放归计划。该研究强调,人们对自由放养的家犬对野生动物的影响缺乏认识,因此需要开展教育。在保护区执行无犬政策至关重要,但兽医诊所的缺乏带来了挑战。家犬数量管理问题复杂,有效的家犬数量管理需要家犬主人、地方政府和保护管理人员之间的通力合作。

Plain Language Summary

thการศึกษานี้สำรวจปฏิสัมพันธ์ระหว่างสุนัขกับสัตว์ป่าในชนบทของประเทศไทย โดยเน้นไปที่พื้นที่อนุรักษ์ ด้วยจำนวนสุนัขมากกว่า 900 ล้านตัวทั่วโลก ก่อให้เกิดความกังวลเนื่องจากผลกระทบของสุนัขต่อการคุกคามสัตว์ป่าอย่างน้อย 188 สายพันธุ์ การศึกษานี้มีจุดมุ่งหมายเพื่อทำความเข้าใจมุมมองของชุมชนเกี่ยวกับความขัดแย้งระหว่างสุนัขและสัตว์ป่า และส่งเสริมแนวทางการจัดการประชากรสุนัขที่มีประสิทธิภาพ การสำรวจได้ดำเนินการในภาคเหนือของไทย ซึ่งเผยให้เห็นว่ามีการเลี้ยงสุนัขอย่างกว้างขวาง โดย 50% ของครัวเรือนทั้งหมดที่ศึกษาเลี้ยงสุนัข และมากกว่า 40% เลี้ยงแบบปล่อยอิสระ อย่างไรก็ตามผู้ตอบแบบสอบถามส่วนมากไม่ได้ตระหนักถึงผลกระทบของปัญหาระหว่างสุนัขกับสัตว์ป่า ข้อเสนอแนะจากคนในชุมชนเห็นควรว่าเจ้าของสุนัขควรควบคุมสุนัขของตน ในขณะที่หน่วยงานรัฐระดับท้องถิ่นควรจัดการควบคุมประชากรสุนัข การจัดการที่เหมาะสม ได้แก่ วิธีการที่ทำให้ไม่ถึงตาย เช่น การฉีดวัคซีนและการทำหมันโดยไม่เสียค่าใช้จ่ายสำหรับสุนัขที่มีเจ้าของ และการดักจับ-ทำหมัน-ฉีดวัคซีน-ปล่อยกลับสุนัขจรจัด การศึกษานี้แสดงให้เห็นถึงความสำคัญของการขาดความตระหนักเกี่ยวกับผลกระทบจากสุนัขเลี้ยงแบบปล่อยอิสระต่อสัตว์ป่า

Practitioner points

en

-

Community engagement and collaboration: Practitioners should engage in comprehensive community assessments, collaborating with members to understand local dog ownership norms. Incorporating community preferences into conservation plans fosters support, enhances the effectiveness of population control measures, and ensures solutions are culturally sensitive and community-endorsed.

-

Educational initiatives: Practitioners must prioritise educational initiatives emphasising the ecological impacts of free-ranging dogs. Raising awareness about these impacts can play a significant role in wildlife conservation within and around protected areas.

-

Promotion of responsible pet ownership: Alongside educational efforts, practitioners should promote responsible pet ownership practices. Emphasising the importance of vaccinations and sterilisation can help manage dog populations effectively and mitigate potential threats to wildlife, contributing to the overall success of conservation efforts.

实践者要点

zh

-

社区参与与合作:从业者应参与全面的社区评估,与社区成员合作了解当地的养犬规范。将社区的偏好纳入保护计划可促进支持,提高数量控制措施的有效性,并确保解决方案具有文化敏感性且得到社区认可。

-

教育活动:从业者必须优先考虑强调自由放养家犬对生态影响的教育活动。提高社区居民对这些影响的认识在保护区内及周边野生动物保护方面发挥重要作用。

-

推广负责任的宠物饲养:在开展教育工作的同时,从业者还应推广负责任的宠物饲养方法。强调接种疫苗和绝育的重要性有助于有效管理家犬的数量,减轻对野生动物的潜在威胁,从而让保护工作取得全方面的发展。

Practitioner points

th

-

นักการจัดการควรมีส่วนร่วมในการประเมินชุมชน ร่วมมือกับสมาชิกในชุมชน เพื่อทำความเข้าใจพฤติกรรมการเลี้ยงของเจ้าของสุนัข ผสมผสานความต้องการของคนในชุมชนไว้ในแผนการอนุรักษ์ ส่งเสริมให้มีการจัดการอย่างมีประสิทธิภาพในการตรวจสอบการควบคุมประชากร เพื่อให้มั่นใจว่าการแก้ปัญหาจะสอดคล้องต่อวัฒนธรรมชุมชน

-

นักการจัดการต้องจัดลำดับความสำคัญในการริเริ่มการศึกษาโดยมุ่งเน้นถึงผลกระทบทางนิเวศวิทยาของสุนัขที่เลี้ยงแบบปล่อยอิสระ และส่งเสริมแนวทางปฏิบัติในการเป็นเจ้าของสัตว์เลี้ยงอย่างมีความรับผิดชอบต่อสังคม เช่น การฉีดวัคซีนและการทำหมัน

1 INTRODUCTION

The dog (Canis familiaris) was, and is, the first and only large species of carnivore to be domesticated by humans. Fossil evidence of this domestication spans the globe, with the earliest remains recorded in Belgium, estimated to be 36,000 years old (Freedman & Wayne, 2017). Throughout history, dogs have significantly influenced human society, serving in various capacities such as home guards, hunting companions, herders on farms, service animals and sources of companionship (Hart & Yamamoto, 2016). Nowadays, they have been shown to improve their owners' lives in many ways, including increasing their level of physical activity and reducing psychological stress (Kramer et al., 2019). Despite this long-standing history of positive human–dog interactions, significant direct and indirect conflicts that arise due to domestic dogs remain.

1.1 Negative impacts from domestic dogs

The impact of domestic dogs on wildlife and the conflicts arising from these interactions have received increasing interest from conservation biologists studying human–wildlife conflicts. This surge in research interest is largely driven by the need to develop more evidence-based solutions for managing these risks (Young et al., 2011). Doherty et al. (2017) reported that 188 wildlife species were threatened by domestic dogs. However, in regions like Southeast Asia, the actual number is estimated to be five times higher (Marshall et al., 2022). Along with creating new vectors for disease transmission, domestic dogs can disrupt ecosystem function through competition, disturbance and predation (Hughes & Macdonald, 2013). Managing domestic dog populations presents social challenges due to the difficulty in distinguishing between different categories of dogs. For example, feral dogs are entirely independent of humans for resources. In contrast, stray dogs, which may be abandoned or are ownerless, often still depend on humans or live near human settlements to access resources (Makenov & Bekova, 2016). Free-ranging domestic dogs, though owned, are not confined and have the freedom to roam into natural habitats surrounding their community unaccompanied by their owner (Torres & Prado, 2010). In many low- and middle-income countries, dogs often lead free-ranging lifestyles, which geographically heightens the potential for conflicts with wildlife (Vanak & Gompper, 2009). Although most free-ranging dogs stay close to their homes, instances of them foraying up to 28 km away have been recorded. The length of forays is often influenced by factors such as age and sex, with older or male dogs tending to foray more intensely (Saavedra-Aracena et al., 2021). In response to the potential negative impacts on wildlife, managers of natural and protected areas often implement additional restrictions, such as requiring dogs to be leashed and restricting their access to certain areas. However, the enforcement of these regulations is not consistent and largely depends on the voluntary compliance of dog owners (Schneider et al., 2020).

In addition to the direct threats to wildlife from free-ranging dogs, global health authorities are increasingly concerned about their role in transmitting zoonotic diseases. Domestic dogs are known as major reservoirs for viral infections such as rabies and norovirus, and bacterial infections such as Leptospira, Salmonella and Pasteurella (Ghasemzadeh & Namazi, 2015), many of which can be fatal to humans. Additionally, free-ranging dogs pose physical dangers to humans, not only through attacks (Tenzin et al., 2011) but also as a significant cause of animal–vehicle collisions, with approximately 80% of such incidents involving dogs (Canal et al., 2018). Finally, these dogs can exacerbate conflicts with farmers and community members who keep livestock. In a study by Home et al. (2017), dogs were found to be the primary culprits of livestock depredation, more so than native carnivores, which are often unjustly blamed.

1.2 Conservation management implications

The body of knowledge regarding socioecological conflicts with dogs from across the world is growing; new insights from Madagascar (Kshirsagar et al., 2020), Chile (Schüttler et al., 2018; Silva-Rodríguez & Sieving, 2012) and Australia (Williams et al., 2009) have been instrumental in building a strong evidence base in support of the action. Despite studies highlighting the risks dogs pose to wildlife in Southeast Asia (Doherty et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 2022), data from this region remains limited. Thailand, in particular, has been identified as the most at-risk country, with nearly 70% of its natural areas perceived to be at risk from domestic dogs (Marshall et al., 2022). This is not surprising as only 22% of rural dogs in Thailand are restricted in their movements through leashes or confinement. Consequently, the majority of free-ranging dogs, which are also less likely to be vaccinated than their confined counterparts (Kongkaew et al., 2004), pose an increased risk of disease transmission to both humans and wildlife.

Protected area management remains the predominant approach for addressing biodiversity declines and safeguarding habitats (Watson et al., 2014). Typically, these areas tend to be established away from cities in lower income rural areas (Joppa & Pfaff, 2009). However, the creation of these protected areas can lead to restrictions on resources that local communities had historically accessed freely, potentially impacting their livelihoods (Coad et al., 2008). Therefore, community participation is vital to the success of these conservation projects, as it can effectively bridge the gap between environmental protection and local interests, thereby reducing potential conflicts. (Wibowo et al., 2018) Additionally, such participation is key in devising better solutions that can balance trade-offs between conservation goals and community needs (Rudd et al., 2011). Consequently, to better understand the community perspective of dog–wildlife conflict in protected areas and to promote effective population management methods, households across a rural district in Northern Thailand were interviewed to address the following objectives: (1) to provide information on current husbandry practices in the area, establishing a baseline for future comparative data; (2) to gain insights into the issues caused by domestic dogs within the community; (3) to examine local perceptions and experiences of dog–wildlife conflict; and (4) to explore population management options and identify parties responsible for their implementation.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study area

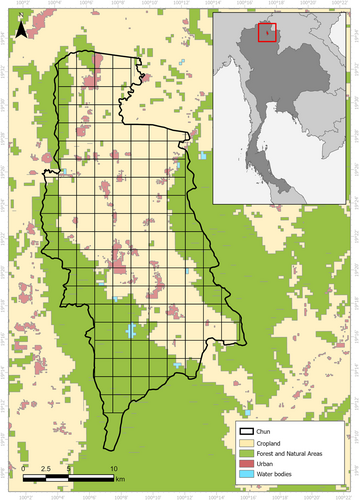

The survey was conducted across the Chun District (Figure 1) of Phayao Province, located in Northern Thailand near the border with the Lao People's Democratic Republic. This province is primarily inhabited by Eastern Lanna ethnic groups, known for their unique Northern dialect (Seangpraw et al., 2019). Chun District encompasses 86 villages, housing approximately 7062 households, with a population of 18,867 spread over an area of 570 km2. The province has a notably ageing population, most of whom work in agriculture and have little formal education (Seangpraw et al., 2019). Within this district, two protected areas can be found: Tub Phaya Lor Wildlife Nonhunting Area and Wiang Lo Wildlife Sanctuary. These protected areas consist primarily of dry dipterocarp and mixed deciduous forests. They serve as habitats for endangered species, including dhole (Cuon alpinus), Sunda pangolin (Manis javanica), green peafowl (Pavo muticus) and large-spotted civet (Viverra megaspila), all of which are perceived to be at medium or high risk from the presence of domestic dogs (Marshall et al., 2022).

2.2 Data collection

2.2.1 Sampling

A grid system, each measuring 2 × 2 km in size, was overlaid across the study area. This approach was adopted to ensure that study participants resided within the targeted district and to facilitate the ease of data collection. Grid cells with an area of less than 2 km2, particularly those located on the border of the district, were excluded from the study area. As a result, a total of 130 grid squares were included in the study. Interviews were conducted in January 2022, with up to 15 households interviewed in each grid square. In cases where a cell contained 15 or fewer households, all households were approached for participation. In cells that contained more than 15 households, random sampling points were generated, and households closest in proximity to these points were selected for interview. If a selected household was unoccupied at the time of the visit, the next closest household was selected. To ensure accurate data collection, respondents who were not available at their homes were asked to identify their household location on a map. This method was employed both to avoid interviewing respondents multiple times and to confirm their home was within the designated study area.

2.2.2 Instruments

Questionnaires encompassed a variety of questions on domestic dog husbandry, wildlife conflict and domestic dog management practices (Material S1). The survey consisted of 48 questions, split into seven sections. These sections requested information on dog ownership, care provided to respondents' dogs, free-ranging dogs in the local community, zoonotic diseases, dog–wildlife conflict, dog intervention methods and sociodemographic information. If participants did not own a dog, the section on dog husbandry was accordingly omitted.

The questionnaire consisted of both open and closed questions. Closed questions included single-selection, multiple-choice, or Likert-type scales. There were eight 7-point Likert-type item statements in the questionnaire. Respondents were asked to rate each statement ranging from one to seven, where ‘one’ signified ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘seven’ indicated ‘strongly agree’. In the analysis, each response was assigned its corresponding numerical value. Scores over 4 were interpreted as positive answers, those below 3 as negative answers and 3 as neutral answers.

2.2.3 Translation

The questionnaire was developed in English before being translated into Thai. Translations were carefully reviewed by bilingual colleagues against the original English version to ensure accuracy and clarity. The Thai version of the questionnaire underwent further revisions and edits based on feedback obtained during the pretesting phase, which included feedback from test respondents.

2.2.4 Research ethics and pretesting

Before the main survey, a pilot test was conducted on six respondents to identify and correct any ambiguous questions or mistranslations. In terms of participant eligibility, respondents were required to be part of a household within the Chun District, 18 or over, and only one respondent per household was permitted to participate in the survey. Participants were explicitly informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time or choose not to answer specific questions. Verbal consent was obtained from participants for the use of their data for publication. The surveys, conducted in Thai, were administered by three Thai researchers and responses were recorded electronically using Google Forms. The study received ethical approval from the human ethics committee of the King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT-IRB-COE-2020-055).

2.2.5 Statistical analysis

Initially, descriptive statistics were calculated to summarise basic demographic and husbandry information from the interviews. To assess differences in respondent preferences for various dog management methods, Pearson's χ2 test was used. Open-ended questions were sorted into distinct groups based on similar answers and coded accordingly. To visually represent common themes and their frequencies, word clouds were then generated using the ‘ggwordcloud’ package (Pennec & Slowikowski, 2019) in the R statistical environment.

To examine the factors influencing respondents' perceptions of dog–wildlife conflict and approaches to dog population management, cumulative link models (CLMs) were employed from the package ‘ordinal’ (Christensen, 2015) in the R programme. CLMs analyse ordinal response variables where responses are ordered and categorical. The models focus on determining the cumulative probabilities of observing a specific response category, or a category of higher order, based on various predictor variables (Christensen, 2015). The Likert statements ‘I think dogs negatively impact wildlife in my local reserve’ and ‘I believe that dog populations should be managed to stop them increasing’ were analysed using CLMs. For each statement, a ‘global model’ incorporating all relevant predictor variables was created (File: S2). To identify the most informative models, we employed the ‘dredge’ function from the ‘MuMIN’ package (Barton, 2018) to generate a set of candidate models. Before this, all variables were tested for correlation using Cramer's V from the package ‘rcompanion’ (Mangiafico, 2017). All models with a delta akaike information criterion < 4 were considered to be equally supported and were selected for further analysis. This subset of models was then used to create an averaged model, a technique beneficial for large model sets to account for model selection uncertainty (Grueber et al., 2011). The ‘model.avg’ function in the ‘MuMIN’ package was used to create the averaged model (Barton, 2018).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic characteristics of respondents

Overall, 350 responses were collected from Chun District, representing approximately 5% of the households in the area. Of these respondents, 199 identified as female (56.9%), and the remaining 151 as male (43.1%) (Table 1). Most respondents were aged between 40 and 60 (48.9%, n = 171). The most common occupation in the district was farming (43.7%, n = 153), although this was sometimes subsidised with a side business. Merchants comprised the next largest occupational group (19.7%, n = 69) (Table 1).

| Variable | Number (n = 350) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 199 | 56.86 |

| Male | 151 | 43.14 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 9 | 2.57 |

| 25–39 | 49 | 14.00 |

| 40–60 | 171 | 48.86 |

| 60+ | 120 | 34.29 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.29 |

| Person/household ratio | 3.4 | - |

| Occupation | ||

| Contractor | 30 | 8.57 |

| Farmer | 136 | 38.86 |

| Farmer with side business | 17 | 4.86 |

| Housewife/husband | 32 | 9.14 |

| Merchant | 69 | 19.71 |

| Retired | 17 | 4.86 |

| Other | 49 | 14.00 |

3.2 Husbandry practices in rural Thailand

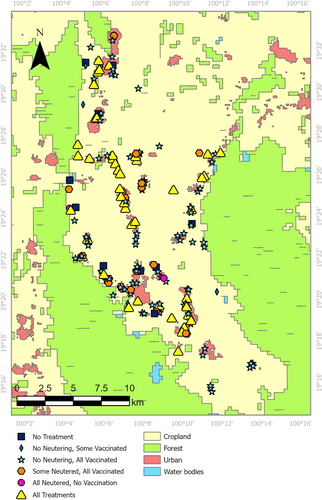

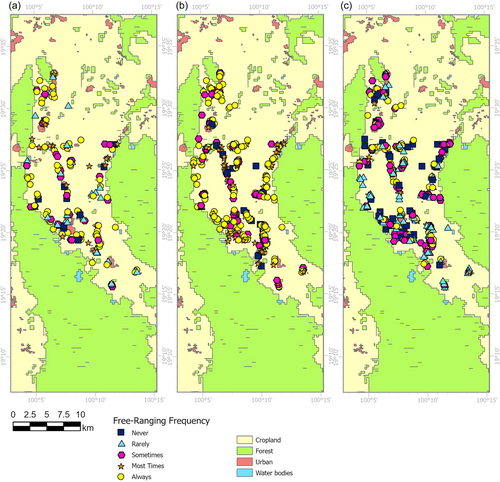

According to the survey, 174 (49.7%) households owned dogs (Table 2), accounting for a total of 370 dogs. The majority of these dogs had a free-ranging lifestyle, with 41.9% of respondents stating their dogs were always free-ranging and only 18.4% always restricting their movements. In terms of how these dogs were acquired, most had obtained at least one dog from their neighbours (71.8%, n = 125). Guarding was the primary reason for keeping dogs (70.7%, n = 123), followed by companionship (53.5%, n = 93). Farming (6.9%, n = 12) and hunting purposes (1.7%, n = 3) were the least common reasons.

| Variable | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Owns dog | (n = 350) | |

| Yes | 174 | 49.71 |

| No | 176 | 50.28 |

| Free-ranging | (n = 174) | |

| Never | 32 | 18.39 |

| Rarely | 11 | 6.32 |

| Sometimes | 31 | 17.82 |

| Most times | 27 | 15.52 |

| Always | 73 | 41.95 |

| Neutered | (n = 174) | |

| All | 47 | 27.01 |

| Some | 20 | 11.49 |

| None | 107 | 61.49 |

| Vaccinated | (n = 174) | |

| All | 155 | 89.08 |

| Some | 6 | 3.45 |

| None | 13 | 7.47 |

| Dog/household ratio | 1.06 | - |

| Items dogs are feda | (n = 174) | |

| Scraps | 116 | 66.67 |

| Dog food | 93 | 53.45 |

| Rice and meat | 41 | 23.56 |

| Special diet | 13 | 7.47 |

| Foraging | 11 | 6.32 |

| Hunting | 1 | 0.57 |

| Acquired dog froma | (n = 174) | |

| Breeder | 27 | 15.51 |

| Neighbour | 125 | 71.84 |

| Adopting a stray dog | 32 | 18.39 |

| Breeding own dog | 9 | 5.17 |

| Reason to keep dogsa | (n = 174) | |

| Guarding | 123 | 70.69 |

| Companionship | 93 | 53.45 |

| Like dogs | 62 | 35.63 |

| Empathy for stray dogs | 26 | 14.94 |

| Farming | 12 | 6.70 |

| Hunting | 3 | 1.72 |

- a Respondents could select multiple answers.

Owners reported a diverse range of feeding practices for their dogs. A significant proportion, two-thirds of respondents, stated they fed their dog(s) scraps (66.7%, n = 116). Several owners reported introducing new foods or varying the diet to prevent dogs from becoming bored with their meals. Over half of respondents fed their dogs commercial dog food (53.5%, n = 93). Among households with more than one dog, only two respondents reported feeding their dogs differently, attributing this to dogs' preferences and specific medical needs. Even though 96.6% of respondents stated that their dogs had slept on their property in the past week, only 21.4% of respondents purposely restricted their dogs' movements at night through fences, cages or keeping their dogs inside the house.

Regarding neutering practices, 27% (n = 47) of respondents indicated that all their dogs were neutered (Figure 2), whereas 61.5% (n = 107) had not neutered any of their dogs. The remaining 11.5% (n = 20) had neutered some but not all of their dogs. The main reason cited for not neutering all their dogs was due to a belief that male dogs do not need to be neutered (n = 59). Seventeen respondents mentioned their female dogs had been given contraceptive injections, and 12 stated that their dogs were too young to be neutered. There were 44 respondents who confirmed their female dog had had a litter of puppies that year. Finally, 89% (n = 155) of respondents had vaccinated all their dogs, while 7.5% (n = 13) had not vaccinated any, and 3.4% (n = 6) had vaccinated some.

3.3 Community perspectives on free-ranging dogs

The survey revealed that the predominant attitude towards dogs in the community was neutral (31.1%, n = 109). When asked to elaborate, the most common themes (Figure 3a) were the absence of problems related to dogs in their community (n = 85), enjoyment of having dogs around (n = 35) and that there were no strays in the area (n = 33). However, 22.2% of respondents (n = 78) strongly disagreed with the notion of enjoying dogs in the community. The most common negative responses were that free-ranging dogs attacked people (n = 32) and that they were loud (n = 23). Nearly half (49.4%, n = 173) of respondents stated that their neighbours habitually allowed their dogs to roam freely and alone (Figure 4). In comparison, only 2% (n = 7) indicated that their neighbours never let their dogs roam unaccompanied. When asked if they had seen any unknown dogs in their community in the past week, 36% (n = 126) had not observed any. On the other hand, 23.7% (n = 83) frequently encountered unknown dogs in their vicinity.

When it was inquired if they fed free-ranging dogs in the community, 59% (n = 207) of respondents answered that they never did so. In contrast, only 12.3% (n = 43) regularly fed community dogs, while 27.4% (n = 96) sometimes provided food to these dogs. A marginal 1.1% (n = 4) chose not to answer the question.

Lastly, when queried about what responsible dog ownership meant to them, the most frequently cited aspect by respondents (Figure 3b) was providing adequate food for the dogs (n = 84). This was followed by the importance of caring for the dog, with some respondents comparing it to the care given to children (n = 74). Other trends included restricting their movement (n = 47), ensuring vaccinations (n = 43), preventing them from disturbing neighbours and other community members (n = 41) and taking financial responsibility for any harm caused, such as medical expenses for attacks on people or pets (n = 33).

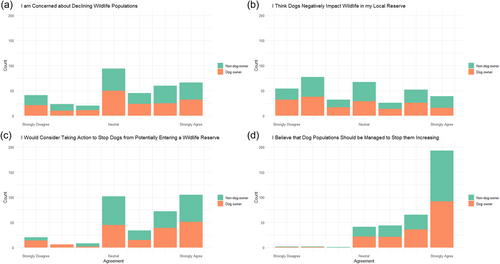

3.4 Dog–wildlife conflicts

The largest proportion of respondents gave a neutral response when asked if they were concerned about declining wildlife populations (26.9%, n = 94) (Figure 5a). However, when queried about the impact of domestic dogs on wildlife in the local reserve, the response was predominantly negative (Figure 5b). Factors that negatively influenced this response included dog ownership and being male (File: S3). Additionally, witnessing dogs attacking wildlife in the local reserve within the past month appeared to positively influence participants' perceptions regarding the impact of dogs on wildlife. Similarly, seeing stray dogs within the community, regardless of frequency, also seemed to positively sway respondents' answers. However, it is important to note that none of these variables reached statistical significance.

When asked about the possible negative impacts of domestic dogs on wildlife (if any), most respondents stated that dogs do not impact wildlife (38.6%, n = 135). However, 25.7% (n = 90) mentioned dogs chasing wildlife as a negative impact. Other notable responses included hunting (16.3%, n = 57), attacking wildlife (13.7%, n = 48) and transmitting diseases (3.1%, n = 11). Twenty (5.7%) respondents were unsure. When asked if they had seen dogs in the wildlife reserve in the past month, 18.0% (n = 63) stated that they had, whilst 48.9% (n = 171) stated they had not. A sizeable percentage of respondents (32.6%, n = 114) either did not know or had not visited the reserve during that time. Two respondents (0.6%) chose not to answer this question.

Regarding the observation of wildlife attacks by dogs in the past month, a majority of respondents, 50.6% (n = 177), reported not witnessing any, 40.9% (n = 143) were not sure, and one respondent chose not to answer (0.3%). Of the 29 respondents (8.3%) who had witnessed attacks, the species listed included junglefowl (G. gallus), green peafowl (P. muticus), Burmese hare (Lepus peguensis), tokay gecko (Gekko gecko), unidentified monitor lizards, snakes, tortoises, macaques, rats, squirrels and birds. In addition to the previously mentioned species, respondents were asked to identify other wildlife that they believed might be impacted by dogs. This list included larger mammals commonly targeted by hunters, such as wild boar (Sus scrofa) and unidentified muntjacs. Other species mentioned, not previously listed, were civets, cats, egrets, frogs, insects, moles and weasels. Interestingly, one respondent noted the interaction between domestic dogs and golden jackals (Canis aureus), describing it as an interaction rather than a chase or attack.

3.5 Dog management practices and responsibility

An overwhelming majority of respondents, both dog owners and nondog-owners, believed that dog populations did need to be managed (Figure 5d). Factors that positively influenced this belief included dog ownership, witnessing neighbours' dogs roaming freely, being over 25 and observing dogs in the local reserve in the past month, with the latter found to be statistically significant (p = 0.00) (File: S3). Negative predictors of this belief included being male if the respondent was a farmer, owning a dog and enjoying the presence of dogs in the community. Interestingly, a neutral stance on enjoying dogs in the community (Likert response 2) was found to positively influence the belief in the need for dog population management.

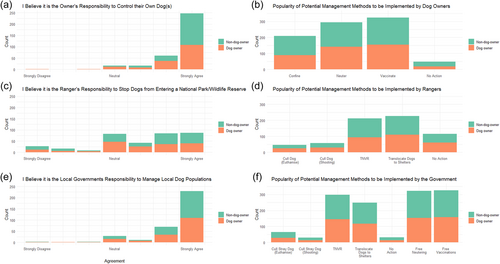

Most respondents strongly believed that dog owners should be responsible for controlling their own dogs (n = 246) (Figure 6) and acknowledged the duty of local governments in managing dog populations. In comparison, the emphasis on rangers' responsibility was less than that of owners or the government. Although a large portion of respondents expressed some degree of agreement in taking action to prevent their own and their neighbours' dogs from entering the reserve, a considerable number provided a neutral response to this question (n = 102) (Figure 5c).

When asked about measures that owners could implement (Figure 6), the most favoured option was vaccination (n = 324), followed by neutering (n = 295) and then confinement (n = 209). A smaller portion of respondents (48) chose ‘No action’, with the caveat that respondents could select multiple management methods. The age of respondents was found to be significant to their selection of management methods (File: S3), with the exception of vaccinating owned pets (p = 0.07). Dog ownership status also influenced choices; the majority (68%) of nonowners favoured confining owned dogs (p = 0), while vaccination was selected by 90% of owners (p = 0).

In terms of ranger-implementable measures, the most favoured option was translocating dogs to shelters (n = 226), followed by trap-neuter-vaccinate-return (TNVR) (n = 212). ‘No action’ was selected by 115 respondents. Less popular were culling methods; specifically, culling via lethal injection was chosen by 46 respondents, while culling via shooting was chosen by 58. The age of respondents significantly influenced their opinions on culling via injection (p = 0.01) and TNVR programmes (p = 0.03) (File: S3). Whether or not they worked as a farmer influenced their preference for ‘no action’ (p = 0.01) and for translocating dogs to shelters (p = 0). Dog ownership affected the selection of TNVR (p = 0.01), with over 65% of nonowners supporting this approach.

Preferences for government-implemented measures included offering free vaccinations to owned dogs (n = 326), providing free neutering for owned dogs (n = 322), TNVR programmes for unaccompanied dogs (n = 298) and translocating stray dogs to shelters (n = 249). Less popular options comprised culling stray dogs via lethal injection (n = 65), taking no action (n = 32) and culling stray dogs via shooting (n = 30). Respondents' age was found to be a significant variable for several management methods, including culling via shooting (p = 0), free neutering programmes (p = 0.03) and free vaccination programmes (p = 0.01) (File: S3). Additionally, whether the respondent worked as a farmer affected responses to culling via shooting (p = 0.04) and choosing ‘no action’ (p = 0.03). The only significant influence of dog ownership was observed in responses to the free vaccination programme (p = 0.03).

When asked about additional suggestions to address dog–wildlife conflict or other related thoughts, respondents suggested measures such as fenced houses, increased ranger numbers, dog registration and fines for owners whose dogs entered protected areas. Some mentioned relocating captured dogs to shelters rather than the community, although concerns were expressed about potential noise issues in shelters. Many respondents also stated that dogs were not a significant problem in the area, attributing wildlife decline in the forests more to human impacts than to dogs. The idea of restricting human access to the forest was mentioned based on the observation that dogs typically follow their owners into these areas.

4 DISCUSSION

In the rural landscapes of Southeast Asia, particularly in Northern Thailand, dogs are a ubiquitous presence. However, there is a limited understanding of how these dogs are cared for and the prevailing attitudes towards them within the local community. This knowledge gap makes introducing effective management practices to the area challenging. The concern is heightened with nearly 42% of dog owners in our study not restricting their dogs' movements, coupled with a dog-to-household ratio of 1.06:1. This high rate of unrestrained dog movement increases the potential for interactions between humans and dogs, as well as between wildlife and dogs. Such frequent contact can elevate the risk of disease transmission, attacks, harassment and other negative outcomes (Vanak & Gompper, 2009). Despite the potential impact domestic dogs can have on wildlife, it appears to be widely underestimated in the region. Only 18% of respondents reported having seen dogs in the reserve in the past month. According to a recent study, domestic dogs were found to be the second most detected species, excluding humans, in the neighbouring protected areas (Marshall et al., 2023). This marked discrepancy highlights the need for a more comprehensive assessment of community attitudes and perceptions regarding domestic dogs. A deeper understanding of the interactions between domestic dogs and wildlife is imperative to help produce informed conservation strategies.

4.1 Husbandry practices in rural Thailand

Our interviews revealed that nearly half the households in the area owned one or more dogs, with three-quarters of these dog owners acquiring them from their neighbours. This trend is corroborated by the fact that 44 respondent-owned dogs had had litters within the past year. A significant concern is the low rate of neutering observed in the region; over 60% of dog owners reported not neutering any of their dogs. This issue, coupled with the prevailing lack of movement restrictions among the majority of dogs, suggests a substantial contribution to the growth of the local dog population. The percentage of dogs neutered in Chun, while higher than some countries such as Mexico (3.1% and 11%) (Orozco et al., 2022; Ortega et al., 2007) and Guatemala (6.3%) (Pulczer et al., 2013), remains much lower compared to others such as New Zealand (78.5%) (McKay et al., 2009) Italy (65.8%), Bulgaria (32.6%) and Ukraine (27.9%) (Smith et al., 2022). In a study by Totton et al. (2010), a domestic dog population would remain stable with a neutering rate of approximately 31%. However, to achieve a population decrease from its original size, at least 69% of the population would need to be sterilised. As this study only focused on owned dogs, it is likely that the overall sterilisation rate is much lower than reported. Many respondents believed that only female dogs required sterilisation, and, whilst this may be true if the household does not want a litter of puppies from their own dog, it fails to consider any stray or community dogs in the area who have not been neutered. To effectively manage and decrease the overall dog population, sterilisation measures must extend beyond owned dogs to include stray and community dogs as well.

4.2 Community perspectives of free-ranging dogs

Even though many respondents expressed a neutral response to their stance on free-ranging dogs, prompting for further explanations revealed a list of negative impacts, including attacks, noise, disturbances and defecation. This neutrality may be influenced by social pressure, considering nearly 50% of respondents noted their neighbours' dogs lived a free-ranging lifestyle. In Chun District, the percentage of respondents who actively feed community dogs was much lower than in other areas, such as the Bahamas (53%) (Fieldling & Mather, 2000), Bangalore, India (52.2%) (Bhalla et al., 2021) and Goa, India 37% (Corfmat et al., 2023). Additionally, when asked about responsible dog ownership, a substantial portion of respondents mentioned actions that would decrease interactions between dogs and community members. These actions included stopping attacks, paying for injuries caused by dogs, preventing dogs from disturbing neighbours and overall control of their behaviour. This perspective contrasts with studies in the United Kingdom, where responsibility was primarily directed towards the dog itself rather than its impact on others (Westgarth et al., 2019). Although not the most frequently mentioned action, restricting dogs' movement could potentially address these issues, suggesting that promoting more stringent movement control may be a key aspect of fostering responsible dog ownership in the community. Interestingly, walking or exercising pets was not raised in discussions about responsible pet ownership, despite the recent rise in pet-friendly parks in the nation's capital (Marshall et al., 2022). This omission suggests that the concept of actively exercising pets is not widely incorporated into daily life in the study area, likely due to the independent nature of most dogs there. Consequently, although confining pets might resolve community issues, there is a possibility of welfare-related worries arising from insufficient exercise for confined dogs.

4.3 Dog–wildlife conflicts

The vaccination rates, in comparison to sterilisation rates, were much higher, with 89% of respondents indicating that all their dogs had received vaccinations. This finding is crucial considering the role of domestic dogs in the transmission of multiple diseases to wildlife, including rabies, canine distemper and canine parvovirus (Berentsen et al., 2013). A notable example is the suspected involvement of domestic dogs in an outbreak of canine distemper that led to a crash in lion (Panthera leo) numbers in the Serengeti in 1994 (Roelke-Parker et al., 1996). Domestic dogs also act as reservoirs for diseases that can affect vulnerable populations, including the endangered Southern river otter (Barros et al., 2022). The risks extend beyond wildlife, with significant implications for human health. In Bali, domestic dogs were responsible for 92% of rabies cases, all of which were fatal (Susilawathi et al., 2012). Similarly, in South Africa, domestic dogs were responsible for 75% of human rabies cases (Weyer et al., 2020), and in China, this figure was 84% (Guo et al., 2018).

Whilst a lack of vaccination and sterilisation of domestic dogs can impact wildlife through disease transmission and potential hybridisation (Hughes & Macdonald, 2013), wildlife can also be affected by disturbance, predation and interspecific competition (Doherty et al., 2017). Although only a small number of respondents witnessed domestic dogs directly attacking wildlife, notable incidents included attacks on green peafowl, a species vital for ecotourism in the area (Saridnirun et al., 2021). The number of respondents who reported negative interactions between domestic dogs and wildlife in our study was much lower than in comparable studies; Orozco et al. (2022) reported that 23% of respondents in Central Mexico had witnessed such interactions. Yet, the protected areas surrounding Chun District consist of fragmented forests where large, charismatic wildlife species have become locally extinct. Many respondents reported a perceived absence of wildlife remaining in the protected areas. This could possibly be due to limited time spent in the area or a narrow association of ‘wildlife’ with only the larger, charismatic species, such as tigers (Panthera tigris) and elephants (Elephas maximus), being well known in the country. Despite this perceived absence of wildlife by some locals, the protected areas are home to endangered and vulnerable species, including green peafowl, dhole (C. alpinus), Sunda pangolin (M. javanica), Northern pig-tailed macaque (Macaca leonina) and sambar (Rusa unicolor) (Marshall et al., 2023). Notably, species such as green peafowl, dhole and Northern pig-tailed macaque have been identified as being at high risk of impact from domestic dogs (Marshall et al., 2022). This information highlights the need for effective measures to prevent dogs from entering these areas. Given the ecological impacts of domestic dogs in protected areas, they should be classified as invasive species, highlighting the need to address these impacts and the necessity for their removal. The protected areas located in Chun District experience notable human and livestock traffic (Marshall et al., 2023), which necessitates a focused management strategy. The initial emphasis should be on mitigating this traffic and strictly prohibiting individuals from taking their dogs into the protected areas. Given the close proximity of these areas to settlements and their small size, completely eradicating dogs may not be feasible. Nevertheless, developing and implementing an action plan to diminish their presence is crucial, reducing their numbers in the surrounding areas and regulating access points, thereby helping to mitigate their ecological impact (Lessa et al., 2016).

4.4 Dog management practices and responsibility

The survey results indicate a general consensus amongst respondents that dog owners should be responsible for controlling their own dogs, while local governments should be responsible for managing their populations. Unsurprisingly, there was minimal support for lethal control in this study area, which aligns with the prevailing Buddhist beliefs in the region. These beliefs often extend to the reluctance of vets to practice euthanasia (Phutchu, 2021). Although translocating dogs to shelters was a common response as a viable management strategy, it presents a challenge since there are currently no known dog shelters in the area. The feasibility of using such shelters is also problematic, particularly if these facilities are not able to practise euthanasia and the trend of acquiring free dogs from neighbours continues. Under such circumstances, shelters risk becoming overrun, which could lead to potential welfare issues. Buddhist temples often serve as makeshift shelters for dogs, cats and other animals that have been abandoned. While these animals can find temporary respite on temple grounds, it is important to note that such facilities are not equipped to provide veterinary care (Thanapongtharm et al., 2021). As a result, the sheer volume of animals can quickly become overwhelming for the monks, given the limited resources available to them (Huo et al., 2019).

The most popular management options for the government to implement are providing free vaccinations and sterilisation for owned dogs, along with a TNVR programme for strays. The local government currently offers a free vaccination programme, which, due to the high number of dogs that have been vaccinated, appears to have been run successfully. This programme should undoubtedly continue, but priority should be directed towards increased sterilisation efforts to reach the 69% neutering rate recommended by Totton et al. (2010). Notably, owners who had not had their dogs vaccinated often stated that the vet had not visited the area or they had missed the visit. There appears to be a lack of veterinary practices in the district, with only one known vet who is also responsible for livestock. This scarcity poses a significant hurdle in effectively implementing a sterilisation programme and would need to be taken into consideration.

4.5 Conclusion

Addressing the issues associated with free-ranging domestic dogs requires a strong focus on education about their impact on wildlife and natural areas. Without community support and pressure, practices that allow domestic dogs to roam into natural areas and interact with wildlife will continue. Whilst the local government has made great steps by introducing free vaccination to the area, further initiatives are needed to encourage owners to confine their dogs on their property and to understand the importance of sterilising their pets, regardless of gender.

Often, when domestic dogs are seen to be impacting animals that have an economic benefit, such as livestock, action will be taken. However, this is rarely the case with species seen as providing only an intrinsic value (Villatoro et al., 2019). In the case of the green peafowl, which is widely celebrated in the area, park managers have an opportunity to extend this sentiment to a wide variety of local species, instilling a sense of pride and stewardship within the community. With the dangers that free-roaming dogs pose to wildlife being recognised around the world (Doherty et al., 2017; Hughes & Macdonald, 2013; Marshall et al., 2022; Villatoro et al., 2019), it is imperative that managers of protected areas take proactive steps to enforce policies to maintain these areas as dog-free zones. Such enforcement not only addresses the immediate threat to wildlife but also plays a vital role in shifting community perspectives towards more responsible dog ownership practices. Effective policy implementation and community education can reduce the number of dogs left to roam freely within protected areas, thereby safeguarding the diverse species that inhabit these crucial ecosystems.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Holly E. Marshall: Conceptualisation; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; supervision; validation; visualisation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. Meredith L. Gore: Conceptualisation; methodology; resources; supervision; writing—review and editing. Dusit Ngoprasert: Conceptualisation; formal analysis; methodology; resources; supervision; writing—review and editing. Tommaso Savini: Conceptualisation; methodology; resources; supervision; writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of Jiratchaya Tananantayot, Rawin Ruenroeng and Suthaphat Sangiam as our field assistants. Their hard work and dedication were crucial to the successful completion of our research project. We also extend our thanks to Jiratchaya Tananantayot and Prapasiri Sutthisom for their assistance with translations, which greatly enhanced the quality of our work. We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback, which greatly improved our manuscript. Lastly, we acknowledge the important logistical support provided by the Rangers of Wiang Lor Wildlife Sanctuary, which enabled us to carry out our research safely and effectively. H. E. Marshall was supported by King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi's Petchra Pra Jom Klao Ph.D. Research Scholarship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the human ethics committee of the King Mongkut's University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT-IRB-COE-2020-055).

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Archived research data sets are not available for this submission due to the confidential and anonymous nature of the data collected from human participants. The data can be made available upon request.