The Mystery of Waugh Syndrome: Unraveling a Rare Diagnostic and Surgical Enigma

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Waugh Syndrome should be considered in a pediatric patient presenting with acute abdomen with features of intussusception, even when symptoms mimic acute gastroenteritis. Clinicians, particularly pediatric surgeons, must be aware of this condition for timely diagnosis and treatment to prevent the complications.

1 Introduction

Acute intussusception is a condition where there is telescoping of one bowel loop into the next section [1]. It is the most common abdominal emergency in early childhood and the second leading cause of intestinal obstruction after pyloric stenosis [2]. Its peak incidence is between 5 and 9 months of age, with only 10%–25% of cases occurring after 2 years of age [3]. Intestinal malrotation is an anomaly due to the abnormal rotation and fixation of the intestine [4]. In embryonic life, the midgut rotates to approximately 270° counterclockwise around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery [5]. Intestinal malrotation occurs due to arrest in the normal rotation of the embryonic gut, and its exact incidence is not known because rotational anomalies may become asymptomatic throughout one's life [6]. Association between intussusception and intestinal malrotation is a very rare entity, and this rare coexistence was first described in three boys, all aged below 3 years, by George E. Waugh in 1911 [7]. Later, in 1986, this association was named Waugh Syndrome (WS) by Brereton et al. [8] in their prospective study in patients with intussusception conducted between 1981 and 1983. To our knowledge, less than 100 cases of WS have been reported to date in the literature [9] and this is the first case to be reported from Nepal. This report underscores the importance of expanding our knowledge of this uncommon syndrome, aiming to understand its presentation, management, and outcome. Due to the limited number of reported cases, clear treatment guidelines have not been established. Preoperative preparation, involving intravenous fluids and electrolyte correction, is essential before surgical intervention. The typical and widely employed treatment approach in most of the reported cases involves open surgery to manually reduce the intussusception, followed by the Ladd's procedure for addressing intestinal malrotation. This case has been reported in line with SCARE 2023 criteria [10].

Herein, we present the case of a four-year-old child with Waugh syndrome, who initially presented with features of Acute Gastroenteritis (AGE). Upon evaluation for ileoileal intussusception as shown by abdominal ultrasonography (USG), the rare condition of WS was unexpectedly discovered during exploratory laparotomy. Along with the release of intussusception, the Ladd's procedure was performed.

This case is being reported to highlight its rarity and to discuss the diagnostic challenge associated with this syndrome.

2 Case History/Examination

A four-year-old male was brought to the pediatric out-patient department with a three-day history of loose stools, vomiting, and abdominal pain. The stool was initially watery but became mixed with blood and mucus over 2 days. He experienced around six to seven episodes of loose stool daily, with each episode measuring about 30 mL. The mother also noted vomiting, which was acute in onset, non-projectile, non-bilious, not blood-stained, and approximately 20 mL per episode, containing food particles. The child also reported pain in the abdomen for 3 days, localized to the periumbilical region, mild, non-radiating, with no clear aggravating factors, and relieved by defecation. There was no history of fever, headache, painful urination, jaundice, right iliac fossa pain, or constipation.

3 Methods (Differential Diagnosis, Investigations, and Treatment)

The patient was admitted to the pediatric ward and initially treated for AGE, but symptoms persisted. Blood investigations revealed leukocytosis (12,100/mm3), mild anemia (hemoglobin 11.4 g/dL), hypoalbuminemia (3.0 g/dL), and hypoproteinemia (5.8 g/dL). Serum electrolytes showed mild hyponatremia (Na+ 134 mmol/L), while potassium (K+ 4.8 mmol/L), urea (27 mg/dL), and random blood sugar (82 mg/dL) were within normal limits. Renal function tests revealed subnormal creatinine (0.5 mg/dL; reference: 0.72–1.18 mg/dL). Coagulation studies showed a marginally elevated prothrombin time (15 s; control: 14 s) with normal INR (1.09).

Stool examination revealed reddish, semi-solid stool, and positive for blood and mucus. Stool microscopy revealed plenty of red blood cells (RBCs) with 0–1 pus cell per high-power field. No cysts, ova, or parasites were detected.

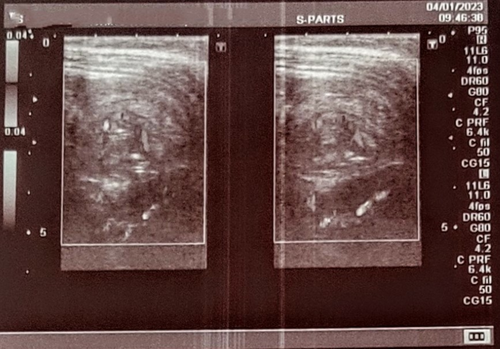

Abdominal USG revealed ileoileal intussusception in the left hypochondrium, measuring approximately 2.75 cm in diameter, with preserved blood flow on doppler imaging, along with enlargement of adjacent mesenteric lymph nodes (Figure 1).

Conservative management consisting of Nothing Per Oral (NPO), intravenous fluids, and antibiotics was started in line for mesenteric adenitis as a possible etiology in a view of spontaneous resolution of intussusception, but even after 24 h of conservative treatment, there was no resolution, and abdominal radiography showed features of bowel obstruction; thus, exploratory laparotomy was performed. Based on clinical and USG findings, the preoperative diagnosis was ileoileal intussusception. Considering the competency of the ileocecal valve, non-operative hydrostatic or pneumatic reduction was not attempted.

4 Treatment Outcomes and Follow up

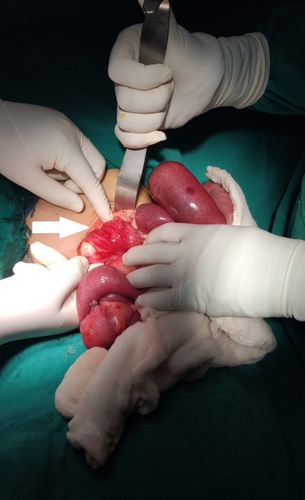

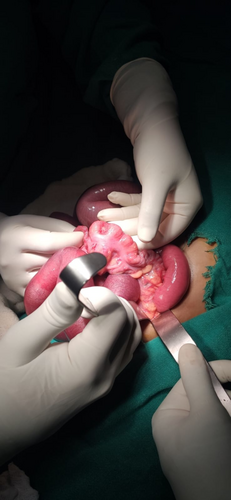

During laparotomy, ileocecal intussusception was confirmed, with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes at the ileocecal junction identified as the lead point (Figure 2). Hypertrophic Peyer's patches and viable intussusceptum were observed, along with an incidental finding of gut malrotation and Ladd's band (Figure 3). Thus, WS was diagnosed incidentally. Initially, manual release of ileocecal intussusception was performed (Figure 4). Then, the Ladd's procedure with appendectomy was performed. In the same setting, the cecum was fixed to the posterior abdominal wall to prevent its recurrence. Subsequently, there were no complications throughout recuperation for the child.

5 Discussion

The association of intussusception and intestinal malrotation is an exceedingly rare entity termed Waugh syndrome [5]. To date (as of 2024), less than 100 cases of this syndrome have been reported in the literature so far [9].

Intussusception occurs mostly at the ileocecal junction, although ileoileal, jejunojejunal, jejunoileal, or colocolic intussusception can occur. The diagnosis of intussusception relies on clinical observations, including abdominal pain and signs of bowel obstruction such as episodic colicky pain associated with drawing knees to the chest, and episodes of excessive crying and irritability, with the child appearing normal between episodes. Other features are vomiting, passage of red currant jelly stool, and a palpable sausage-shaped mass in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium on the abdomen. Though these classical features may not be present in all cases of intussusception, ultrasound is the initial investigation of choice in the diagnosis of intussusception [2]. Similarly, our case exhibited a range of symptoms including loose stools, vomiting, and abdominal pain, resembling AGE upon presentation. The presence of leukocytosis prompted us to initiate treatment consistent with AGE. However, as symptoms persisted despite initial conservative management, an abdominal and pelvic USG was performed, which revealed ileoileal intussusception in the left hypochondrium with enlarged mesenteric nodes. In approximately 90% of cases, the etiology of intussusception is idiopathic, most likely due to lymphoid hyperplasia acting as a lead point [11]. In our case, intra-operative findings revealed enlarged Peyer's patches and telescoping of the ileum into the colon, confirming the ileocecal type of intussusception. However, due to intestinal malrotation, the ileocecal intussusception was located in the left hypochondrium, which led to a false impression of an ileoileal type on USG. This underscores the diagnostic complexity of differentiating ileoileal from ileocolic intussusception in the setting of intestinal malrotation, where aberrant anatomy can distort typical imaging findings. Notably, the ileocecal intussusception in our patient presented atypically in the left hypochondrium—a location we had not previously encountered in clinical practice. This anatomical anomaly, compounded by malrotation, contributed to the preoperative misclassification as ileoileal intussusception. The unexpected displacement of the ileocecal junction underscores how rotational abnormalities can mimic small-bowel intussusception on imaging, reinforcing the need for heightened suspicion in atypical cases.

Computed tomography (CT) scans can be time-consuming for children, often requiring sedation, and expose them to significant radiation. Therefore, CT is typically reserved for cases where other imaging techniques, like ultrasound, fail to provide conclusive results or when further characterization of a pathological lead point in intussusception is needed [12]. Thus, a CT scan was not performed in our case, and the diagnosis of malrotation was purely an intraoperative incidental finding. Had we known about the possibility of underlying malrotation previously, then we would have definitely done a CT scan of abdomen, but there was no indication for CT since our preoperative diagnosis was solely ileoileal intussusception based on clinical and ultrasonographic findings. Thus, this case emphasizes the role of CT scan in any case of intussusception to look for associated malrotation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can serve as a cross-sectional imaging technique similar to CT for detecting signs of malrotation [13].

Intestinal malrotation is a rotational anomaly of the developing embryonic gut, and its exact incidence is not known since many cases are asymptomatic [6]. Ladd's band is a fibrous structure extending from the cecum and ascending colon to the upper retroperitoneum. This congenital band, if present with malrotation, causes intestinal obstruction [14]. Approximately 90% of cases with malrotation present within the first year of life, of which 80% present in the neonatal period [15], with characteristic bilious vomiting due to duodenal obstruction caused by midgut volvulus due to this band [16]. While older children beyond the neonatal period may have nonspecific symptoms like bilious or non-bilious vomiting, chronic abdominal pain with or without vomiting, malabsorption, and constipation, which may delay the diagnosis and management of malrotation in older kids [4, 14, 17]. Similar presenting symptoms of malrotation can be attributed in our case too. The discovery of Ladd's band alongside intestinal malrotation during surgery was an unexpected finding that likely contributed to the observed bowel obstruction.

In comparison to ileocolic intussusception, small bowel intussusception is more likely to reduce spontaneously, particularly if the intussusceptum is short. Also, it is less likely to respond to nonoperative reduction methods [12, 18]. The same principle was applied in managing our case, where after demonstration of ileoileal intussusception by USG, we did not try enema reduction considering the inability of air or fluid to pass beyond the ileocecal valve.

A prospective study by Brereton et al. reported a 40% incidence of malrotation among children with intussusception. The disparity between the frequent occurrence of WS in this study and its rare mention in published literature suggests that numerous cases may go undetected. This could be due to non-surgical resolution of intussusception through air or contrast enema, where radiological signs of malrotation might not be evident, especially when guided by ultrasound [8]. Thus, if exploratory laparotomy had not been conducted in our case, the diagnosis of WS might have been missed.

Therefore, when diagnosing intussusception, it is essential to consider WS. Clinicians, especially pediatric surgeons, must be aware of this rare syndrome for timely diagnosis and treatment to reduce morbidity and mortality due to this acute abdominal condition.

This case report underscores the rarity of this often-overlooked syndrome and emphasizes the necessity for additional research to enhance understanding of its actual incidence, pathophysiology, presentation, diagnosis, and clear treatment guidelines in a more comprehensive manner.

Author Contributions

Sanjay Dhungana: resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Jasmine Bajracharya: conceptualization, project administration, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Kshitiz Kayastha: writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Bineet Thapa: supervision, writing – review and editing. Bipu Dhakal: supervision, writing – review and editing.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.