Translating the Lampung Oral Literature into Music for Educational Purpose: A Case Study of Pisaan on the Indonesian Island of Sumatra

Abstract

A large body of data concerning oral literature around the globe have been reported. Moreover, in Indonesia, a country with multilingual and multicultural contexts, the study of oral literature has become an important aspect of investigation. One of the oral pieces of literature that exists in Indonesia is Pisaan, an oral tradition that can be found in Lampung, a province located on the southern tip of the island of Sumatra. Although a considerable amount of oral literature research has been conducted in the Indonesian context; however, to our best knowledge, little research has been paid to Pisaan oral literature, which plays an essential role in the Lampung community. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the oral literature by translating and transforming the Pisaan oral literature into lyrics and musical elements to educate future generations. This study adopted a qualitative approach using several instruments, i.e., semistructured interviews and recording tools, for data collection. A total of four women who were cultural activists in the age range of 37–76 years of age took part in the current study. The collected data were analyzed using a content analysis and a melody structure analysis. The results show that Pisaan has simple syllabification, which dominantly consists of consonant–vowel (CV) and consonant–vowel–consonant (CVC). The rhythm of Pisaan is categorized into syllabic time syllables, emphasizing the stress word based on its syllables. From a musical perspective, the Pisaan oral literature has been successfully translated and written into musical notation with the aim of preservation, which, as far as we are aware, has never before been done. However, we realize that the Western music notation in this study only serves as the initial stage of analysis and does not aim to replace the distinctive native-cultural values of Pisaan, offering an alternative instructional path for improving Lampung oral literature teaching methods and a valuable strategy to diversify undergraduate courses through comparable interdisciplinary inquiries. Therefore, limitations and suggestions for future research are also discussed.

1. Introduction

A large body of data concerning oral literature around the globe have been reported [1–4]. Oral literature itself refers to a subset of the massive field of knowledge widely recognized as “oral tradition” or “orality,” a communication system in which information and messages are passed down verbally from one generation to the next. The terms “oral literature” and “folklore” are sometimes used interchangeably to refer to the aspects shared by a group, such as language and belief systems, contributing to a community’s cultural, and national identity [4]. In Indonesia, a country with its multilingual and multicultural contexts [5–7], the study of oral literature has become an important aspect of investigation [8–10].

One of the oral pieces of literature that exists in Indonesia is Pisaan, an oral tradition that can be only found in Lampung, a province located on the southern tip of the island of Sumatra [5, 11, 12]. Today, Pisaan serves to function as a tool to express oneself in various situations and conditions, for example, when releasing the departure of a child to get married, the grief left by the parents, and lamenting the state of themselves and others. It is also used by the people of Lampung to date as a medium for da’wah and to increase people’s appreciation of traditional arts and literature [13]. In some places, it is used as part of traditional processions and shows. On the one hand, these shows can be hardly found among the urban communities in Lampung, on the other hand, this kind of oral literature needs to be preserved as a means for teaching moral, ethical, and religious values to future generations [14], representing the Lampung identity. Therefore, various parties, including educators, academics, and government, should work hand-in-hand to “save” this oral tradition and one way to achieve this is through music [15].

It is well-accepted that oral literature departs from oral tradition in general [16], referring to what is said and sung [17], one of which is through music [18] to transfer educational values of the oral literature [19]. However, the medium of transferring the values through formal education institutions, such as elementary and secondary schools, has not been formulated yet. Hence, translating the Pisaan oral literature into music as an interactive and fun teaching medium to make the young generations take part in the preservation and educate them the moral values of the oral literature need to be taken into account.

Pisaan, such as poems, should be transmitted orally [17] through music. The melody of Pisaan should be well recorded and transformed into syllabification to find out the number of syllables within each line. The rhythm is considered to identify the intonation of the syllables for the whole Pisaan. Rhythm is related to articulation and pronunciation, and sound is categorized as the term melody. Melodies in musical studies require tones. Tone patterns will imitate through the scale (tone, barrel) tone. This study involves music analysis to determine the form of presentation of the Lampung literature in full, seen from the melodic, scale, and interval aspects. In the domain of melody and rhythm, the oral literature of Lampung has different prosody. The musical style determines the characteristics of pronunciation [20]. In so doing, it is expected that the Pisaan oral literature can be easily documented for preservation that can be passed down through generations. Therefore, although a considerable amount of oral literature research has been conducted in the Indonesian context, but to our best knowledge, little research has been paid to the Pisaan oral literature, which plays an essential role in the Lampung community. Hence, it was worthwhile to conduct this study by translating and transforming the Pisaan oral literature for the purpose of educating future generations.

2. Literature Review

Lampung is located in the Indonesian island of Sumatra’s southern tip. The province is home to various ethnic groups, with the indigenous Lampung, Javanese, Balinese, Sundanese, and Palembang constituting the majority. Lampung’s indigenous groups are classified as Saibatin and Pepadun. As a result, the two indigenous groups are collectively referred to as “sai bumi ruwa jurai” (a land consisting of two ethnic groups) [21, 22]. The Saibatin people are often referred to as “peminggir” due to their predominance in the coastal area [21, 23], while the indigenous people of Pepadun are primarily concentrated in interior places, such as Kotabumi, Gunung Sugih, Sungkai, Tulang Bawang, and Pubian [24, 25].

The indigenous Lampung people follow a philosophy called “pi’il pesenggiri.” The fundamental values contained in pi’il pesenggiri are as follows: (1) pi’il pesenggiri (moral, having a sense of shame); (2) sakai sambayan (assisting others, communal work); (3) nemui nyimah (politeness); (4) nengah nyappur (mingling with the community); and (5) bejuluk beadek (keeping a reputation) [22, 26–30]. Apart from being a way of life, pi’il is frequently used as a cultural defense mechanism against foreign communities and ethnic immigrants [29].

In addition, Lampung ancestors enjoyed expressing themselves through oral tradition. According to previous research, oral poetry literature is classified into different types: pepatcor, pattun (rhyme), Pisaan (a type of poetry), bebandung, and paradini [13]. The Lampung’s oral tradition was previously only passed down orally, raising concerns that it will become extinct, because oral traditions are only found in traditional ceremonies, such as when awarding a name to newly-born children in traditional activities (adok). In addition, students responded positively to the oral tradition after it was introduced into the school curriculum. As a result, schools play an essential role in preserving the Lampung’s oral tradition [31]. Pisaan can be used to help students improve their ability to appreciate literary works, especially when learning the Lampung language and culture [32].

The Lampung oral literature is spoken in Lampung language that is passed down orally and is distributed in a verbal form (now it has been inventoried, and many have been written). This oral tradition is anonymous and belongs to the Lampung ethnic collective. The oral tradition is widely distributed in the community, which is an essential part of Lampung’s ethnic culture and national heritage [33, 34]. Lampung literature is classified into two types: prose and poetry. Lampung prose is mostly myth, legend, and fable, while, poetry is in the form of pantun, syair, and Pisaan. All of the various types of Lampung literature have a purpose, either as an educational tool, religious advice, or entertainment [35].

Pisaan is a type of Lampung–Pepadun poetry that is prevalent in the Pubian, Sungkai, and Bunga Mayang communities. It is used as a prelude to traditional ceremonies, as a complement to dance, such as cangget, and as a form of leisure time entertainment [36]. According to a study of Pisaan of the Pubian community, it states that: (1) the theme of divinity and humanity dominates the inner structure of the Pisaan; (2) “speakers” tend to advise or patronize readers, namely entertaining and advising readers to choose things that are positive, both in the worldly and in the hereafter; (3) the emotional atmosphere that characterizes it is an atmosphere of longing for an ideal life, in accordance with religious and social norms; (4) the mandate offered in the chapters is quite varied, in that the reader is encouraged to be able to live life in accordance with Islamic religious norms as well as social norms; (5) its didactic values cover a wide range of topics, including intellectual and intelligence aspects, skills, self-esteem, social society, morals, beauty, emotional stability, behavior, divinity, and will; and (6) divine and human values predominate in the inner structure and values didactic [37].

Pisaan derives from folklore and contains many positive values such as moral and cultural education [19]. Pisaan research is still ongoing, and it even includes a musical approach [38]. Thus, as stated by Pratiwi et al. [31] and Amziyati et al. [32], it can foster special learning in the classroom. Smith and Raswan [39] have also recorded Pisaan in Lampung, though more research is needed to translate and analyze its text.

In terms of musical development, phonologists use the term syllable to describe any type of sound pronunciation that requires complex processing [40]. In this regard, music theorists use the term rhythmic, in which the unit that creates sound is correlated with note duration in music. Similar to syllables, rhythmic patterns can reveal durational structure and the relationship between notes and rest, enabling musicians and other practitioners to perform, read, and improvise rhythms more skillfully. Rhythmic music is recognized as a distinct form with sound and rest. Notation is used to help identify the sounds, along with their values for each sign, to make it easier to identify them.

3. Methods

This study adopted a qualitative approach using several instruments, i.e., semistructured interviews and recording tools, for data collection. A total of four women who were cultural activists in the age range of 37–76 years of age took part the in current study. The first informant was a 60-year-old woman with Lampung–Javanese ethnic group background. The second was a 37-year-old native Lampung woman. The third and the fourth were native Lampung women aged 58 and 76 years, respectively.

This study consists of multiple stages, including (1) recording, (2) scale recognition, (3) transcription of sonic sound into musical notation (staff), (4) synchronization of each stanza’s rhyming, and (5) conclusion (Figure 1). The recording process was conducted as a musical study of acoustic data. We evaluated the recorded speech (melody) using sonic sound, which was linked to the notation–translation process. Utilizing the synchronization rhyme, vocal and melodic patterns were compiled. When practicing Pisaan, each performer or research participant employed standard scales, such as pentatonic. Thus, the rhyming scheme and the melodic structure were connected. After then, a significant effort was made through the sequential process to complete the intricate Pisaan vernacular style.

The semistructured interviews were conducted with the participants to find out how they learned the Pisaan and look at their understanding of the oral literature more deeply. After the interviews, we asked them to write down the Pisaan lyrics. After the writing, we then asked them to sing it. Finally, we asked their permission for recording the tone of the Pisaan they were singing. The recording process was done in a soundproof room.

Once the recorded data of the oral literature were obtained, we transformed the pieces of the Pisaan into notations. We recorded using a laptop and a USB audio interface type Focusrite: Scarlett 2i2 studio (with specifications: Scarlett 2i2 audio interface, Scarlett Studio CM25 condenser mic, Scarlett studio headphones, 10′ microphone cable, exclusive software bundle). These tools were used to get clear and precise recorded voice accents because accents produce a melody since reading and singing are the same [41, 42].

The collected data were analyzed using content and melody structure analysis. The former, for analyzing the interview results, refers to the subjective interpretation of text data’s content via a systematic classification process that involves coding and identifying themes or patterns [43]. The latter refers to a music analysis to look at the tonality, scales, and interval of the Pisaan. We captured the melody’s notes on tape and then used precise pitch scales, such as diatonic and pentatonic, to interpret the melody’s pattern. The melodic production of each performer varies from the intended pitch, but overall, the pattern tends to fit into the existing Western-tone system. It should be noted that the use of Western musical systems in this paper only serves as an initial analytical tool and does not undermine the authenticity of indigenous culture in Pisaan. This analysis aimed to reflect a melodic pattern that will be used for educational purposes rather than impose local culture. Moreover, the Lampung people have more access to knowledge of Western music because they have been exposed to the formal curriculum in schools, including diatonic and pentatonic scales.

The next step was to use music analysis and description to explain the findings of the melody. The three criteria used to define scales were tonality, pitch, and interval. To examine scales, we analyzed the set of notes that composed the melodic system (tonality). Then, by observing pitch and interval, the melodic pattern related to the key signature was identified; the sound was then turned into a Western musical notation to clearly show our analysis. Our research participants produced a single-layer melody that followed their natural path. During recording, each participant creates musical lines, each with a unique set of frequencies. None of them had the idea of tuning systems, such as equal temperament. The recording session was conducted as naturally as possible. We drew an early conclusion regarding the melodic scale by identifying the scale’s key signature. Interval is a component of the melodic scale; it reveals the pattern of the distance between notes, whether they are close together on average or have a fairly large disparity.

The frequency of sounds was visualized (in Hz) during the initial recording for Pisaan vocalists using Tony-melodic transcription. The Center for Digital Music at the Queen Mary University of London was the original developer of this app [44]. This app easily identified notes by locating the waveform in a piano roll visualization layer. Then, a pitch track visualization played back the vocalists’ recorded files.

The procedures of the music analysis were as follows: the recording audio was changed into a “wave” file format with a bitrate of 16 bits and a sample rate of 44.1 kHz to analyze its form, analyzing the sequential intervals that rely on the aspects of the melody [45] in which there are notes, motives, phrases, sentences [46], and tone scales. The elements of musical parameters, melody intervals, and tone notes [47] were used to categorize the patterns. The patterns written in the notation were used as a communication tool [48] for Pisaan that can serve to function as a learning medium. The analysis was performed by equating the tuning to the piano instrument, A = 440 Hz. After the melody patterns were obtained, the next step was to determine the beginning and end tones at the end of each line and the Pisaan. This process was carried out to conclude the melody patterns used. After the musical transcription, once the Pisaan was fully illustrated using notation, we could finally form a system and develop a model for teaching and learning the Pisaan oral literature. Notation can be used as a visual tool to determine the extent to which Pisaan melodies can be taught, as well as the melody’s complexity and reproducibility. This phase is essential to the extrapolation of Pisaan-musical pedagogy. As a musical workflow, Western musical notation was paired with a Tony-melody transcription approach in order to examine Pisaan from multiple musical perspectives.

4. Results and Discussion

Pisaan is still used in traditional ceremonies and official government functions. Pisaan vocalists (singers) are indigenous to the Lampung people of Pepadun in Way Kanan, Sungkai, and Pubian areas. Pisaan text writing is done in accordance with the theme of the event or event under discussion. Each Pisaan text contains a piece of advice for anticipating future events or learning from history, transmitted based on oral tradition, which is still used today. Writing texts necessitates a wide range of specialized knowledge and experience. The four informants under investigation stated as follows:

Informant 1:

… Pisaan texts are still learned in villages, but they are rarely found in cities. I moved to the city for school and work, so I’ve missed out on a lot of Pisaan knowledge.

Informant 2:

Pisaan has extraordinary values, so it still has to be taught as Lampung’s identity. However, because of lack of interest, its existence is threatened with extinction. Singing Pisaan requires some skills and knowledge, with the ability to communicate fluently in Lampung’s native tongue.

Informant 3:

Pisaan’s values are very deep, especially moral, educational and divine values. The Pisaan study helps a person to recognize his/her identity as it teaches ethics that have been inherited from his ancestors.

Informant 4:

I learned Pisaan in the past from my uncle and grandfather; nearly all children were required to learn the oral tradition. With the passage of time, no Pisaan is now required to learn.

It is very clear from the results of the interviews that Pisaan contains very strong elements of local values. The development of recording technology, social media, and other broadcasting media can reduce the anticipation of extinction today. What needs to be considered now is how the younger generation can increase their interest in learning Pisaan. After the interviews, the lyric of the Pisaan was obtained from the informants and transcribed in three stanzas as shown in Table 1.

| Pisaan text | Meaning |

|---|---|

|

|

Regarding the syllabification of the lyrics in Table 1, Table 2 shows the identification of the syllabification with a number of syllables.

| Pisaan lyrics | Syllabification | Number of syllables |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Based on the analysis of syllabification, it could be inferred that the three stanzas of Pisaan consist of twelve lines comprising 7–9 syllables each line (Table 2). The number of syllables determines the rhythm of each line which would be discussed in the music elements. Table 3 shows the syllabification based on its pronunciation along with the vowel–consonant arrangement of each line.

| Phonetic symbol | Vowel–consonant arrangement |

|---|---|

|

|

Lampung language consists of V–CV–VC and CVC. It means that the language does not have a consonant cluster. The sounds of “ng” and “gh” in words ngalimpugha in Line 2, ghamik in Line 3, ghua in Line 6, dang in Line 7, gham in Line 8, and ceghita in Line 9 do not mean a consonant cluster because they are consonants of /ŋ/ and /ɣ/. Thus, the vowel–consonant arrangements are categorized into CV. The following explanation is how this syllabification determines the musical elements. The change of the chord occurs at the end of the syllable of each line. By using the standard frequency of A = 440 Hz, we obtained the musical analysis as shown in Table 4.

| Analysis results | Description |

|---|---|

|

|

While recording, the Pisaan vocalists produce varied pitches, although they all use the same pentatonic scale. Without a tuning device, they perceive their fundamental notes and have innate knowledge of their frequency. In order to see the recorded melodic patterns, the audio frequencies are transposed onto the music staff. This step employs a keyboard and guitar with an A = 440 twelve-tone equal temperament to do manual transcription. Based on the standard tuning tone, the pentatonic scale consists of C#–D–E–G#–A and intervals of ½–1–2–½ (Table 4). The four female vocalists created melodic patterns with similar measurements. Based on the sound frequencies of the four Pisaan vocalists, the scale has a similar pentatonic scale pattern (Table 5).

| Vocalist | Melodic lines | Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | C#–D–E–G#–A | ½–1–2–½ |

| 2nd | A#–B–C#–F–F# | ½–1–2–½ |

| 3rd | G#–A–B–D#–E | ½–1–2–½ |

| 4th | G–G#–A#–D–D# | ½–1–2–½ |

5. Pentatonic Scale

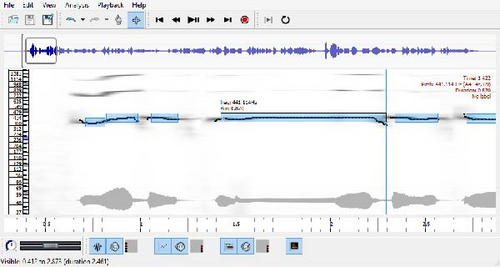

Western musical tradition has commonly equated pentatonic scales with “Chinese,” “exotic,” and “oriental” scales [49, 50]. Almost all Southeast Asian nations, including China, Japan, Indonesia, India, Australia, and Turkey, use the five-tone scale. It is even present in European countries [50]. In this instance, the term “pentatonic” refers to a five-notes-per-octave scale. On the basis of the identification of melodies in all four Pisaan vocalists, the melodic lines and intervals construct nonstandard five-note scales. Similar to the Pelog scale of Javanese gamelan, this sound is produced. Nonetheless, it has overall varying measurements (in cents). Scales in Nusantara music are difficult to standardize because each has a unique character [51]. It is difficult to trace the roots of the pentatonic scale, including in Indonesia, due to the country’s diversified scale notion. Pentatonism asserts that there is no unique pentatonic scale; the five-tone scale notion applies to all traditions worldwide [50]. Geography, ethnicity, and musical traditions have an influence on pentatonic systems. Prior to the conception of pentatonic–Western music, the purportedly prepentatonic musical scale existed. It was an idea in which ancient musical traditions and their scale came first. Figure 2 shows an illustration of a waveform captured by using the Tony-melody app.

As seen in the display of the Tony-melodic transcription program, the default waveform (naturally recorded file) is positioned at the layer A frequency. A has a pitch frequency of 441.114 Hz, which is as near to 440 Hz as the rest note (Figure 2). This waveform represents a sample of the music produced by the first vocalist, and each melodic line approximates each standard frequency in twelve-tone equal temperament. In waveform visualization, the pitch (scales) close to the pentatonic form is frequently displayed. The pentatonic form was utilized regularly throughout the pieces of Pisaan. The sonic sound input to the Tony-melodic transcription also follows the A frequency scales (Figure 3). Thus, the pentatonic form strongly indicates the Pisaan melodic structure or scales.

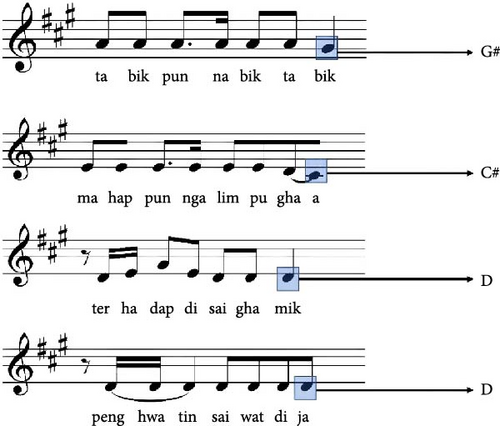

The staff visualization (notation) is used to provide the melody pattern and the endpoint of each pitch or rhyme. In the first stanza, the final pitch has an arrangement of G#–C#–D–D (Figure 4). The endpoint we followed was used to confirm the previous argument regarding pentatonic. As previously stated, the pentatonic form was repeatedly applied to the Pisaan’s melodic structure. The pitch at the conclusion of the melody sound correlates with the acoustic visualizer and notation transcription. Despite the fact that each pitch rhyme does not share the same frequencies, the melodic line in scales is comparable and consists of note groups in A scales principle. We also attempted to ensure the musical structure of each piece by using scales, and observing the repetition of the pentatonic form at the end of the note (Figures 4–6).

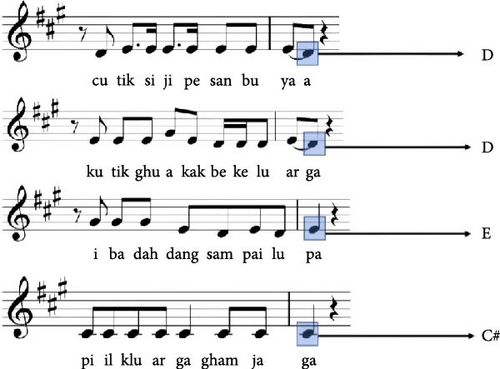

In the third stanza, the endpoint of the pitch has an E–C#–D–C# form. The G#–C#–D–D, D–D–E–C#, and D–D–E–C# patterns are still on the tonality path (Figure 6). Thus, at this stage, we can create a pattern for classroom instructions using a pentatonic scale pattern of tonality and alignment (5 tones). At intervals, the distance of C# to D is half, D to E = 1, E to G# = 2, and G# to A = half.

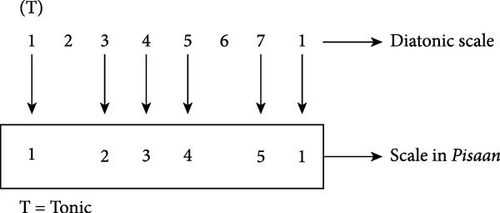

The analysis results show that the melodic pattern contained in the Lampung Pisaan forms a nonstandard pentatonic scale. This result still concludes that the melodic pattern formed has a high tendency for similarity in each note. The melodic patterns that are formed always move constantly in the corridor of the same tone scale, even though the tonality at which they start is different. We employed tonality or standardized frequency to compare how the Pisaan vocalists formed melodic lines and scales. As a result, the pentatonic line frequently forms the Phrygian mode (Table 6). Each Pisaan is composed of multiple repeated stanzas and movement of the melody. This melodic movement appears to exist in all four Pisaan Lampung fragments, but much investigation is required to conclude that it occurs in all Lampung oral literature. Although the scale is widely recognized throughout the archipelago, including Lampung, no records of a specific pentatonic scale in Lampung have been found, nor has any analysis of a unique scale for Lampung music or oral literature been conducted. As a result, the melodic analysis findings are simply contrasted with the following conventional diatonic scale to be comprehended by general readers (Figure 7).

| Musical parameters | Prescription | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Tonality | A = 440 Hz | Frequencies on musical instruments used to discern melodic lines and scales (tempered scale) |

| Scales | Pentatonic–Phrygian |

|

| Interval (pentatonic) | ½–1–2– ½ |

Although we recognize that this melodic movement (pitch) is not particularly exact in the frequency visualization of the waveform, it structurally leads to the previously indicated five-tone pentatonic scale structure. As a result, a more appropriate notation approach is required for future research. We begin the capture of Pisaan in this discussion because oral literature participates in pentatonism. Future studies could address this issue.

Poetry, like speeches, is determined by the speaker, who chooses which words to emphasize and which clauses to include [52]. Music is in its structure by emphasizing the words and clauses. As a result, as initial research, this paper begins with a music analysis approach. In terms of Pisaan, musical elements have contributed to the dialectic song–poem manifest [53]. The identified melodies in Pisaan form a scale with pentatonic tendencies, which is similar to the Javanese pelog system. Pisaan vocalists produce sounds with different tone centers; one person has an E with four sharps (4#), and the rest have different key signatures. However, they all tend to form the same scale, which is pentatonic.

Musical language interface research has extensively investigated the similarities and differences between poetic and musical meter, but has largely ignored melody [54, 55]. The finding of this study indicates that melody serves as the primary unit of analysis for identifying scales. The musical analysis approach seeks similarities in the melodic patterns that comprise the scales; as a result, the pentatonic scales tend to emerge after being analyzed. Hanauer [56] claimed that the parallelistic pattern of melodies can help improve poetry memory due to the supporting memory elements. This paper focuses on the Pisaan, which has an integrated melody. Researchers can easily establish a collective pattern that is used as a general pattern by identifying melodies or scales. This study’s empirical findings support the argument that the melodic aspect of poetry is inherent in the verbal material [54, 57].

In addition, although they tend to form pentatonic scales, as is often the case in West Java and Balinese oral literature, such as pupuh, the number of lines, syllables, and vowel sounds at the end of a phrase may be the same [58], but the contours of the melody differ. The Pisaan has different central tones that, once identified, have similarities with each other. Furthermore, compared to the pentatonic character in Javanese–Sunda, the melody correlates with other local music, such as gamelan degung, whereas there has been no correlation with certain background music in Pisaan.

The transcription of oral literature has composed of oral and written traditions. The process requires remembering, copying, and writing [17, 59]. Oral and written traditions are almost always present simultaneously in the community. The Pisaan poet learns self-taught oral literature. The process involves patterning, sorting, and distinguishing sounds, commonly known as phonemic awareness [60, 61]. If this ability is well managed and organized, it will undoubtedly give birth to new methods to carry on this tradition. Literacy is an indispensable component for poets or chanters of oral literature, such as Pisaan. However, this tradition can be inherited through appropriate teaching methods. A set of skills, abilities, knowledge, and social practices to understand ideological values becomes capital in literacy [62].

Detecting and recognizing individual sounds in music is an essential part of perception [63], although it should emphasize that music notation is primarily designed to serve the sound of production and not for the auditory model. Music notation results from melodic transcription analysis in Pisaan are used as a communication or literature tool for those who teach it later. Although there is no certainty that the foothold is particular, patterns can be made of pitchings or in the literary language of lines, arrays, and sides.

According to the audio data analysis results, the most noticeable results for the media and teaching methods are using the pentatonic tone system, which is nearly identical to Pelog dissolution in Java. Future research should look into ornaments and pronunciation styles. The next stage of the investigation will involve tracing several clans that are still connected to the Lampung Pubian family ties. This medium must be used to determine the character or style of pronunciation. Literacy in musical transcription will give oral traditions such as Pisaan a broad consideration, and people will come to learn, read, practice, and discuss them. Pisaan spread throughout the community via notation. Tradition may soon have an impact on illiteracy. Recognizing local values through literacy learning, particularly notation, will unleash the power of literature [64].

6. Conclusion

In this study, the Pisaan oral literature has been successfully translated and written into musical notation with the aim of preservation. As far as we are aware, this has never before been done. With conscious awareness, we realize that the Western music notation, which in this context had never before been written in any notation, only serves as the initial stage of analysis and does not aim to replace the distinctive native-cultural values of Pisaan. This work represents the initial step in extrapolating the musical pedagogical strategy found in Lampung oral literature, particularly Pisaan, offering an alternative instructional path for improving Lampung oral literature teaching methods and a valuable strategy to diversify undergraduate courses through comparable interdisciplinary inquiries. In other words, in order to teach local oral literature, this work will offer alternative techniques and cultural approaches from a musical perspective.

Moreover, as explained by the informants that Pisaan contains educational values that represent the characters of the indigenous Lampung community, documenting Pisaan through recording media is a perpetual work that continues to be done. Following the current findings of the Pisaan musical elements, future studies could concentrate on the values of Pisaan from the viewpoints of contemporary music, phonology, and other linguistic phenomena, and vocal expressions, such as speech acoustics, musical phrases, and syllable systems, with larger sample size and key informants, to provide more comprehensive conclusions.

The analysis of the musical elements reveals the use of pentatonic scales and tone sounds at the end of phrases is nearly identical to each other; nevertheless, the syllables have distinct characters, distinguishing them from other types of oral literature in Java, like Pelog or Slendro. The tendency of the scales’ similarity to the Javanese version requires further investigation involving more comprehensive anthropologists and cultural experts. Furthermore, it is noteworthy to acknowledge that the pitch inflections of perfect notes in Pisaan are equally outstanding. Other significant characteristics, such as the differentiation of timing, the pitch of contours between notes, loudness, and other auditory characteristics, correspond to each participant. Additional research should investigate some of the aforementioned points in greater depth.

The findings of this current study can also be used to further research to develop an instructional model that integrates syllables and music. The Pisaan musical learning method is expected to pique the younger generation’s interest. By determining the set of melodies using a musical approach, it is anticipated that the Pisaan oral literature will continue to survive. Some young generations may be musically literate while others are not, but a Pisaan musical learning approach is still required.

Given the complexity of Western music notation, which is widely used, we also recommend conducting additional research to provide a more ideal model for learning Pisaan oral literature. In addition, Pisaan is a vocal music form that incorporates microtones. Some melodic notes could be unmeasured or absent from Western common music notation. It is crucial to emphasize that it is strongly recommended that Pisaan be taught in person, using all the required tools and oral traditions, in order to preserve natural characteristics, such as inflection and melodic contour. Finally, this work is undoubtedly only a beginning.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Universitas Lampung, Sunan Gunung Djati State Islamic University, and Universiti Utara Malaysia for their support. In addition, the authors also thank all parties who helped carry out this research.

Open Research

Data Availability

The data and materials used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.