Does education in special care dentistry increase people's confidence to manage the care of a more diverse population?

Abstract

Education in Special Care Dentistry (SCD) at undergraduate and postgraduate levels is often limited when compared with other dental specialities, even though dental professionals encounter people with Special Healthcare Needs (SHCNs) on a very regular basis. This literature review examined whether education at undergraduate and postgraduate level increases dental students’ and professionals’ confidence in managing a patient with SHCN. It also appraised whether there was a correlation between increased practitioner confidence and increased quality of care for people with SHCN. This review also examined educational efforts worldwide, and whether there is an increased emphasis on providing education in SCD to dental students. It was found that those who received high-quality practical and theoretical education on how to properly manage patients with SHCN reported having higher levels of confidence than those who did not. People also reported being far more likely to employ the proper behavior management techniques and were more likely to treat people with SHCN regularly. There has been an increased emphasis on providing education in SCD worldwide in recent years, but a number of barriers still exist to providing complete education in the area.

1 INTRODUCTION

People with disabilities encounter inequities in many aspects of their lives, not least in the medical and dental professions. Society is not yet oriented to cater to the needs of all. Many assume a downstream approach such as that of installing elevators and widening doorframes is the only necessary solution to increase access for those with special needs. While this is effective on a local scale, the upstream approach of educating those who will be caring for the public has proven to be an invaluable asset in the battle for equity. This paper examines the value of educating dental professionals on how to treat those with SHCN and whether it improves their confidence and proficiency.

The purpose of this review is to examine if education leads to increased confidence, and ultimately a change in behavior which leads to improved care for those with SHCN. Increased confidence was utilized as a proxy for behavior change in this review. There are so many factors which affect behavior, from culture to religion to gender to environment, that it is impossible to reasonably measure and predict it. Confidence acts as a good marker of behavior as it is relatively easy to measure and allows people to reflect and self-assess their own behaviors.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Defining special care dentistry

The International Association for Disability and Oral Health (IADH) describes SCD as dentistry for those with a disability or activity restriction which directly or indirectly affects their oral health.1 This may include but is not limited to people with intellectual, sensory or physical impairments, those with mental health issues, complex medical conditions and frail older people.2 Any combination of these special healthcare needs (SHCN) may leave a person unable to maintain their own oral hygiene, make attending a dental surgery particularly difficult or even increase their risk of oral disease based on a pre-existing condition.3-5 Most of these patients may be treated in a primary care setting but for those with more debilitating conditions, specialist treatment may be indicated. There is a paucity of literature describing the demarcation between those who do and do not require SCD. This indicates the importance of all dental practitioners being educated in SCD as patients with SHCN may present for treatment at any time.

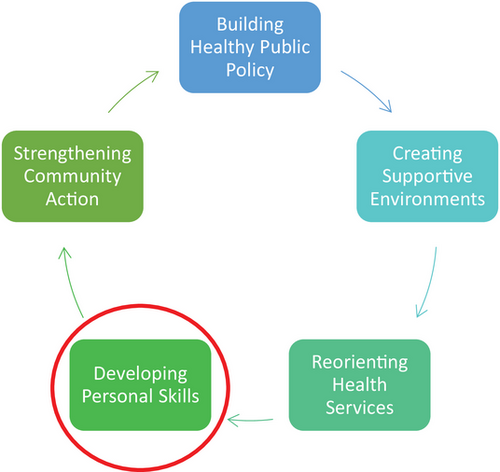

2.2 Developing personal skills

The first International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa, Ontario in 1986. Its main goal was to achieve “Health for All” by the year 2000 and beyond. Evidently, much work remains to be done to achieve this goal, but it did provide a framework, including five headings, to help move towards this ideal situation (Figure 1).6

The Charter recognized the importance of healthcare professionals developing their personal skills when it comes to reducing health inequalities and providing healthcare for all. It plays a vital role in creating a healthcare system in which all citizens, irrespective of socio-economic background, gender, sexual orientation, race or whether they have a disability have equal access to high-quality and effective healthcare.

2.3 Education as a solution—Does it increase confidence?

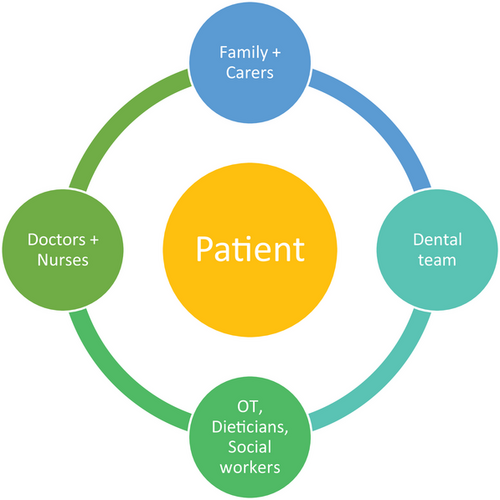

Most of the literature published on education in SCD pertains to dentists and dental students. It must be recognized, however, the importance of educating everyone involved in the care of people with SHCN, including the patients themselves. While the importance of the multidisciplinary approach to oral care for those with SHCN has been noted,7 there is very limited literature to examine whether education in the field increases their confidence to treat this more diverse population. Those involved in an interdisciplinary approach in delivering oral healthcare include carers, family, doctors, nurses, dental nurses, dental hygienists, social workers, dieticians, occupational therapists and physiotherapists (Figure 2).

For the purpose of this literature review, the main focus will be on the education of dentists and dental students as there is the most evidence-based literature available for these groups.

In their series of papers on access to SCD, Dougall and Fiske provided a step-by-step guide on how to educate people with disabilities on oral care.8 Evidence-based recommendations such as modifying toothbrush handles,9 using electric toothbrushes,10 using interdental bushes in lieu of traditional floss and education on denture care were outlined. It recognized the importance of people's right to bodily autonomy and empowering people to practice their own oral care where possible.7 Such guides allow people with disabilities to maintain their own oral hygiene with confidence and dignity.

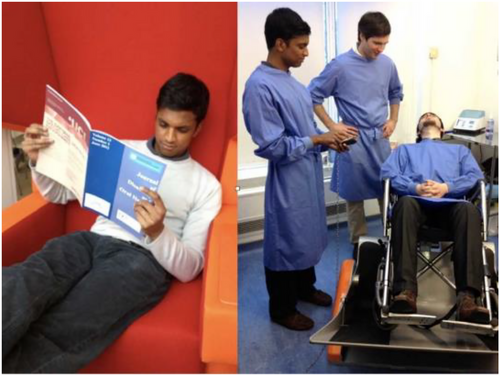

Rohani and Nor conducted a study in which they surveyed 70 fifth-year dental students who had visited a center for children with special needs in Madinah as part of their Special Care Dentistry curriculum. The center treated children with varying SHCN including physical and intellectual disabilities, learning difficulties and behavioral disorders. Figure 3 displays some qualitative data collected with first-hand accounts of their experiences at the center. The responses indicated a deeper understanding of individuals with disabilities along with increased confidence in treating them in a dental setting.11 (Figure 3)

Participants felt that the knowledge and skills gained from their visit to the center motivated them to change their behaviors in both social and professional contexts. This is an overwhelmingly positive result as people with disabilities deserve to be treated with the same respect and dignity as people without disabilities in both clinical and non-clinical settings. In total, 42% of students were able to connect the knowledge they gained with application to their dental practice.11

A study conducted in the USA examining general and pediatric dentists’ attitudes and opinions on education regarding patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) found the more prepared the practitioners felt, the more likely they were to provide care for these patients. The frequency with which pediatric dentists said they used appropriate behavior management strategies when treating patients with ASD was in direct correlation with the quality of their educational experiences.12

Waldman and Perlman described the importance of practical, first-hand experience in treating those with SHCN. They stated that graduates who do not have sufficient experience “will not feel confident inviting these individuals into their private practices.” They also observed that private practices may exclude people with SHCN from their patient pool, favoring referring them for specialist treatment. This may result in newly graduated dentists not attaining sufficient experience even after graduating. Consequently, this may result in dentists who lack confidence in treating people with SHCN and specialist services which cannot meet the demands of all the referrals from general practitioners.13

Casamassimo et al. reported that only about 25% of dentists who participated in their study in the USA had hands-on educational experiences with children with SHCN in dental school. Over 40% of respondents expressed a desire for further training on how to treat children with SHCN (CSHCN). Practitioners who reported receiving both practical and theoretical education on CSHCN were significantly more likely to report that they often or very often treated CSHCN. This strongly indicated a correlation between lack of education in SCD and lack of confidence in working in the area.14

Dao et al. conducted a study of qualified dentists in Michigan to investigate whether undergraduate dental education in SCD affects general dentists’ professional behavior and attitudes towards people with SHCN. The majority of respondents did not feel that their undergraduate dental education concerning the treatment of patients with SHCN had prepared them well. However, dentists who felt well prepared were more likely to treat CSHCN and to provide services for patients with more diverse needs than dentists who did not feel well prepared. Perhaps most importantly, it was found that the more educated and prepared dentists felt, the more confident they felt when treating people with SHCN.15

Ettinger highlighted that exposure alone is not sufficient to increase dental students’ confidence in treating patients with SHCN. The University of Iowa introduced a program in the 1970s to educate dental students in the field of gerodontology. As part of their education, students visited a nursing home to carry out oral screenings and educate residents on denture hygiene. The study found that students actually had more negative attitudes towards older patients after their visit. The study concluded that students did not have sufficient understanding of the normal physiological processes of ageing or the effects of oral disease on the oral cavity prior to attending the nursing home. This indicated the importance of all aspects of education, both theoretical and practical, when looking to improve confidence levels in practitioners.16

In 2015, Lewis et al. noted the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to the oral care of frail, elderly people. The Australian government endorsed the first Nursing Home Oral and Dental Health Plan in 2010. The plan promoted a multidisciplinary approach with doctors, nurses, care workers, dental hygienists and dentists sharing responsibility for oral health screening, daily oral hygiene and access to dental treatment for residents. In this way, it noted the importance of adequate education in oral health for every healthcare professional (HCP) involved in the care of elderly people with SHCN.17

Education is a gateway to improved equality in dental care for people with disabilities. It has also proven to be of benefit in reducing health inequalities for other marginalized groups in society. Dentists who perceived that their dental education had prepared them to treat patients of different ethnic backgrounds or different socio-economic groups than their own were more likely to treat patients in these groups than those who felt ill-prepared by their education. One study concluded that access to oral healthcare for patient cohorts who tend to be underserved could be improved by increased quality and quantity of education in dental schools.18

2.4 Educational efforts

SCD is gathering more recognition as being an integral speciality in dentistry. Postgraduate program are being developed in Australia and New Zealand to train in SCD.19 In Ireland, education on the treatment of patients with SHCN is provided at postgraduate diploma and doctorate levels for advanced dental specialties.3 A Membership Diploma in Special Needs Dentistry from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh has also become available.20 This indicates that dental professionals and educators are becoming aware of the importance of having well-educated, confident practitioners to allow for the safe and efficient treatment of patients with SHCN (Figure 4).

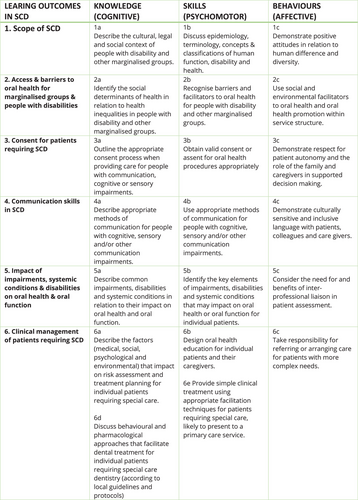

In 2017, the Association for Dental Education in Europe (ADEE) produced guidelines and recommended competencies which should be undertaken by all European dental students—“The Graduating European Dentist”. The ADEE sought to ensure that European graduates are prepared to provide high-quality oral health care for all patients. It also placed emphasis on the importance of the holistic dental team approach to patient care.22 These guidelines provide a framework which can be followed by dental schools to educate their students in SCD. They are not yet, however, a standardized requirement (Figure 5).

The most recent Darzi review of the NHS in the United Kingdom placed emphasis on every citizen, regardless of disability, receiving optimum healthcare to allow them to have the highest quality of life, to live independently, and to retain maximum dignity and respect when in the healthcare system. It encouraged dental practitioners to work in a new way, placing emphasis on educating all members of the dental team in the care of people with SHCN. It also motivated other healthcare providers to incorporate oral care into their holistic care of patients to allow them to have the highest quality of overall health.23

2.5 Barriers to education

- (1)

Inadequate curriculum time—lack of time in the clinical curriculum for new disciplines, an overcrowded overall curriculum and competition among clinical disciplines for curricular time.

- (2)

Inadequate funding—including lack of resources to support geriatric and special care clinics.

- (3)

Lack of trained faculty as teachers for the didactic and clinical courses.24, 25

As a result of these barriers, dental professionals may not be provided with adequate education on treating more vulnerable members of our society.

Ettinger recognized that although there are recommended competencies in SCD, there were no standardized requirements for all dental students. Some practical recommendations laid out in the literature included: revising dental school curricula to be more patient-centered, improving technology in schools, earlier clinical experiences for dental students and visiting community-based clinics. This drew on the concept of Reorienting Health services as outlined in the Ottawa Charter, although in this case, it was the education systems that needed to be reoriented. It is not enough for isolated dental schools to provide specialized education in SCD; there needs to be standard requirements for all graduating dental professionals.24

There is a challenge for dental educators to ensure students undertake the recommended competencies outlined by associations such as the ADEE, even if they are not strict requirements for graduating as a dentist. The literature indicates that increased education leads to increased confidence, and thus more equal access to healthcare for people with SHCN. This places an onus on dental educators to educate future dental professionals.26-29

It is difficult to examine any modern topic without looking at the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on it. The graduating year in the Dublin Dental University Hospital missed out on critical training in SCD which would normally would have been carried out in 3rd and 4th year. They would normally have had the opportunity to shadow a dental team in-person at SCD clinics across Dublin. Unfortunately, this had to be substituted for online lectures and seminars. As a result, the graduating year has had no practical experience in treating those with SHCN and will require either Postgraduate Training or Continued Professional Development (CPD) to gain confidence and experience in how to manage this diverse population. It is highly probable that dental schools across the world will have made the same difficult decisions during the pandemic and that thousands of students will have missed out on in-person educational opportunities. People with SHCNs have also been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic; those with compromised immune systems being required to cocoon or isolate themselves or being unable to be in contact with family and carers to do something as simple as drive them to a dental appointment.26

3 CONCLUSION

Professor June Nunn, one of the leading experts in SCD over the last few decades, is quoted as saying “for the specialty to progress, it is vital that we have accredited training program and external validation of the education and training gained therein.”27 This recognized the immense importance of education in reducing health inequalities and ensuring dental professionals have the confidence and expertise to treat all members of society.

However, more research needs to be carried out on this topic. SCD is a rapidly growing discipline. This means that inevitably there will be a delay in institutions and individuals recognizing its importance. Kraus et al. conducted a study on dental schools’ education in SCD in the USA and Canada. Only 22 of the 65 dental schools contacted responded to this survey. This could indicate a lack of interest and participation in the area of SCD.30

It will be interesting to examine in the coming years the impact the COVID-19 pandemic will have had on newly qualified dental professionals. As Ettinger observed, SCD is already an often-overlooked area in dental schools and the lack of in-person experience will likely have a profound effect on new graduates. The dental profession and education system will likely need to be updated to accommodate both the professionals and the patients who have been affected by the pandemic. This may take the form of mandatory CPD for those who missed out on vital training during the pandemic. Undoubtedly, it will lead to ongoing issues for the area of SCD, where education is already lacking and where patient cohorts were more vulnerable and had more issues with accessing dental care prior to the pandemic.

Education ultimately can only serve to improve dental professionals’ understanding of people with SHCN. With greater understanding comes deeper knowledge, respect and the ability to tackle issues or differences that may arise when treating this patient cohort. The literature indicates that those who receive education at undergraduate level are more confident in both treating those with SHCN and in interacting with them in social settings. When biopsychosocial models of disability, such as that outlined by the IADH are followed, there is a greater understanding that people with disabilities are not less able, merely that society is not oriented to cater to their specific needs. This indicates that HCPs must alter their methods of practise to treat a wider range of people with a variety of needs. While further research can only improve our understanding on the topic, the published literature and personal accounts of people who have experienced high-quality education in SCD indicate education leads to increased confidence and better treatment quality for patients with a diverse range of needs, and thus reduces health inequalities in society.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Open access funding provided by IReL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

There is no conflict of interest in the publication of this article.