Barriers to routine dental care for children with special health care needs

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this mixed method study was to identify barriers for children with special health care needs (SHCN) to receiving routine preventive dental care following restorative dental care with general anesthesia (GA).

Methods

Electronic health records were reviewed for inclusion criteria and demographic data. Caregivers of children with SHCN were contacted to participate in qualitative interviews. Interview topics explored child, family, and community level influences to accessing routine dental care. Qualitative analysis identified key themes of barriers and enablers to care.

Results

A total of 1708 children received dental care with GA during the 2-year study period, of which 498 (29.16%) had a diagnosis of a SHCN. The most common type of SHCN was neurodevelopmental disorders (28.51%). The mean age at time of GA was 8.6 years. Fifty caregivers completed interviews. Identified barriers to obtaining routine dental care included child stress/anxiety, finding an accepting provider, dismissive providers, and proximity of provider/transportation to dental care. Enablers to obtaining care included effective behavior management, continuity of provider/care, positive provider attitude, and referral to an accepting provider.

Conclusion

Adequately trained and local providers with an accepting attitude are essential to enabling children with SHCN to obtain equitable access to routine dental care.

1 INTRODUCTION

Children with special healthcare needs (SHCN), including physical, intellectual, and developmental disabilities, experience a disproportionate level of oral disease that is exacerbated by inequitable access to dental care.1 Providing access to preventive dental care to children with SHCN is an imperative step in improving and maintaining their overall health. 2

A known occurrence in children with SHCN is an increased risk of caries and a decreased prevalence of having a dental home.3-5 Disappointingly, despite the increased risk and prevalence of caries in the pediatric SHCN population, the utilization of preventive dental care in individuals with SHCN is lower than it is in those without SHCN.6

Additionally, many children and adolescents with SHCN receive dental treatment with general anesthesia (GA). While children with SHCN may have medical and behavioral indications for dental treatment with GA, it is also the most medically invasive and costly method of providing dental treatment.7 Furthermore, greater than three-fourths of children with SHCN develop new caries within a year after treatment with GA.8 Children with SHCN who do not access routine dental care following treatment with GA, are four times as likely to require additional dental treatment with GA in the future.ix

Dental caries is a multifactorial disease9 and this disease is inextricably tied to social determinants of health.10 As a result of this, in the current model of dental care delivery, children with SHCN are at increased risk for dental caries, have greater barriers to obtaining preventive dental care, and disproportionately experience GA for dental care. This model is flawed and is apt for intervention at the patient and population level to reduce and prevent dental disease and increase oral health equity. It is important to understand the barriers that families and caregivers face in obtaining dental care for their children. As these caregivers and their children are the primary recipients of interventions and care to improve oral health, understanding their perspective and barriers will enable the public health sector to design more informed interventions for this population.

The aim of this study was to identify barriers and enablers for the population of children with SHCN to receiving routine preventive dental care following dental treatment with GA.

2 METHODS

This study used a retrospective mixed methods design. Inclusion criteria for this study included children with SHCN who had dental treatment with GA at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) from January 1, 2016, through December 31, 2017, and their parents/guardians. SHCN was defined as any physical, developmental, mental, sensory, behavioral, cognitive, or emotional impairment or limiting condition that requires medical management, health care intervention, and/or use of specialized services or programs.11 This study was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board (IRB #21-34319).

2.1 Chart review

A retrospective review of records was completed for children who met the inclusion criteria. Pediatric patients who had received dental care with GA 5 years prior to the study and had a SHCN were included. This timeframe of inclusion was purposely selected, to analyze patients return for dental care over a substantial followup duration following GA. Variables that were collected included patient date of birth, home zip code, primary language spoken at home, the date of GA, and date(s) of visits to the UCSF dental clinic following GA. A primary medical diagnosis for each patient was collected and these diagnoses were categorized into one of 11 major categories of SHCN (See Table 1).

| Chart review demographics (n = , percent) | Interview demographics (n = , percent) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age at GA | 8.6 (SD 6.6) | 8.5 (SD 4.3) |

| Age at data collection for study | 14.5 (SD 6.7) | 14.2 (SD 4.4) |

| Primary language spoken at home | ||

| English | 384 (77.11%) | 42 (84%) |

| Spanish | 70 (14.06%) | 6 (12%) |

| Chinese (Cantonese and/or Mandarin) | 7 (1.41%) | 2 (4%) |

| Other | 7 (1.41%) | – |

| Unknown | 30 (6.02%) | – |

| SHCN primary indication for dental treatment under GA | ||

| Autism/Neurodevelopmental disorder | 142 (28.51%) | 15 (30%) |

| Genetic/Chromosomal abnormality | 98 (19.68%) | 14 (28%) |

| Developmental delay, Idiopathic | 73 (14.66%) | 7 (14%) |

| Cardiac abnormality | 63 (12.65%) | 5 (10%) |

| Cerebral palsy/Seizure disorder | 62 (12.45%) | 7 (14%) |

| Cancer/Oncology | 23 (4.26%) | – |

| Bleeding disorder | 10 (2.01%) | – |

| Skeletal/Connective tissue disorder | 9 (1.81%) | 1 (2%) |

| Non-syndromic craniofacial anomaly | 8 (1.61%) | – |

| Other | 8 (1.61%) | 1 (2%) |

| Dental anomaly (AI/DI) | 2 (0.40%) | – |

2.2 Semi-structured interviews

Parents/guardians of children with SHCN were randomly identified, recruited and consented to participate in qualitative interviews. Contact information for all families that met the inclusion criteria were collected from the electronic health record. This recruitment list was randomized. Each family was attempted to be recruited to participate in an interview two times. If after two attempts the family was not reached and consented, the next family on the randomized list was contacted. Purposeful sampling was also used to identify individuals who spoke different languages, representative of the languages in the larger sample. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish by study personnel, an interpreter was used to complete interviews in Chinese. Two of the authors conducted all of the interviews. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and if needed, translated.

Each interview consisted of a series of open-ended questions related to the parents/guardian's experience in obtaining dental care for their child with SHCN in the 5 years since their GA dental treatment (Appendix 1). This interview guide was designed, revised and piloted with the support of experienced qualitative researchers and an expert on the dental care of children with SHCNs. The semi-structured interview script was designed to follow the standard of trustworthiness in qualitative methods.12

2.3 Data analysis

For the retrospective chart review, descriptive statistics of variables were completed, including frequency for which patients returned for routine preventive visits following treatment.

An open-coding qualitative analysis was used to analyze the responses of the interview participants using qualitative software.13 Key themes of enablers and barriers to maintaining a dental home and accessing routine preventive dental care were identified. These themes included child, family, and community level influences to accessing healthcare, such as physical attributes, insurance, social support, transportation, health behaviors, health system characteristics and other influences as described by the social determinants of oral health model.

3 RESULTS

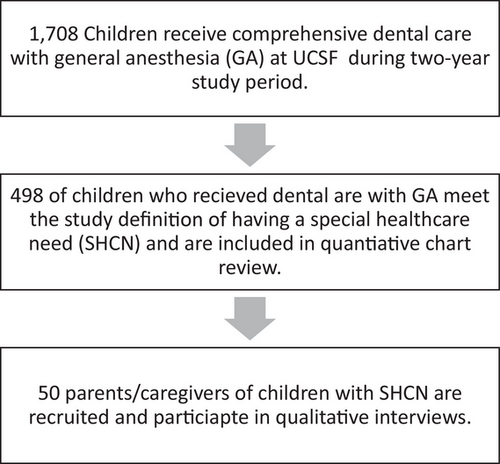

During the 2-year study period there were a total of 1708 children treated with GA at UCSF pediatric dentistry. Of those cases, 498 (29.16%) were children with SHCN that met the inclusion criteria for this study (Figure 1). Prevalence of SHCN by category are shown in Table 1, with autism spectrum disorder/neurodevelopmental disorder most prevalent.

The mean age of the patients at the time of dental treatment with GA was 8.6 years (SD 6.64). The mean age of the patients at the time of chart review was 14.5 years (SD 6.68). The primary language of the families spoken at home were: English (77.11%), Spanish (14.06%), Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin) (1.41%), Other (1.41%), and Unknown (6.02%). On average, families lived 65.8 (SD 55.75) miles from San Francisco.

About two thirds of patients (66.4%) returned to UCSF for at least one dental visit of any kind after their dental treatment with GA. On average, patients returned for their first visit following treatment with GA about 1.5 years (mean days 526.2, SD 409.43) after treatment. On average, patients returned for dental visits at UCSF about every 9 months following GA (sum of total visits during study period divided by total months in study period mean = 8.9 (SD 9.22)). These are both less than AAPD guidelines which would recommend that patients with high caries risk should return for routine dental care every three to 6 months.14

Fifty interviews were conducted with parents/guardians of patients with SHCN. The distribution of SHCN categories for the interviewed families are shown in Table 1.

Several themes about accessing dental care emerged through qualitative analysis of interviews and each was categorized as a barrier or enabler (Table 2). Each of the themes are described below.

| Key barrier themes identified | Key enabler themes identified |

|---|---|

| Child stress/anxiety | Effective behavior management |

| Finding an accepting provider | Continuity of provider/care |

| Provider rapport: Dismissive | Provider rapport: Positive attitude |

| Proximity of provider/Transportation | Referral to an accepting provider |

4 BARRIERS

4.1 Child stress/Anxiety

“He doesn't usually want to go. I have to talk to him and calm him down … he'll get upset and sometimes, he'll swing his arms and I'm driving. So I can't have him in the front, I have to put him in the back seat. He's like, no, I don't want to go.” (interviewee 27)

“He kicks, he throws himself on the floor. He starts hitting his head with his fists or hitting his head against the floor or the wall … Because when we are coming in the building, he starts crying, and whining, … We have to physically hold him in order to get him in. He doesn't walk because he wants to run back to the car.” (interviewee 11)

The parents see their child in distress, and they perceive the often-traumatic experience of going to the dental office as a barrier to maintaining routine dental visits.

4.2 Finding an accepting provider

“So we really couldn't find a dentist that wanted to see [my son]. He's non-verbal. He doesn't really follow instructions. Mentally, he's about 9 months old and he would move and most dentists just perceive that the risk is not worth the prices they charge to get the dental care done. So, the typical response that you get is ‘I'm not equipped to work with a patient that has special needs.’” (interviewee 37)

4.3 Provider rapport: dismissive

“But I just felt like when they [a dentist] see a special needs child or you tell them”, “Oh, my son has autism,” I just felt like they didn't even try. The doctor we had gone to initially wouldn't even look at him, wouldn't even try. He walked in the room and he saw that my son was upset and he was like, “Well, we can't do anything. He needs to be sedated. I won't even attempt’” (interviewee 7)

4.4 Proximity of provider/Transportation

“So we live in the [deidentified]. So from [deidentified] to [dental office] if there was no traffic or accidents, I feel like it would take maybe about, I'll say three-and-a-half, maybe four hours to get there. But if there is traffic, accident, or fires, then I feel like that could take up to 6 hours to get there.” (interviewee 24)

“If I do have to make an appointment, it has to be 2 hours [away] … So I'm kind of hoping like, ‘Oh, okay. Maybe the swelling or the redness will go down.’ Instead of calling the dentist right away. I feel like if it was closer, I might be more prompt to get an appointment for him to just be checked out. But because it's that drive, I hold off on taking him.” (interviewee 38)

“Unless I have that money for gas, I can't guarantee that I can get there because… I might have to cancel it because it is … maybe $300 alone just going down there because you have to pay parking, you have to pay all that, and that's not cheap.” (interviewee 42)

5 ENABLERS

5.1 Referral to an accepting provider

“[I was referred] from his pediatrician. I was having a hard time finding a dentist … So I asked his pediatrician if they can refer me to a dental specialist and they're the ones who referred me to the dentist.” (interviewee 9)

“I was trying to find on the internet, but nobody described anything about special needs appointments”. The only thing that worked was by word of mouth with parents … “Oh, we have the same problem of where to go.” And one of the parents mentioned, “Okay, you can try [deidentified] because they know what to do with special needs.” (interviewee 2)

5.2 Effective behavior management

“We usually use sensory lights to help him calm down, distraction, and I believe he just got his teeth cleaned. He did great. As long as he has all those distractions and they're helping him calm down, he seems okay.” (interviewee 25)

“And so I also have been doing a lot of visual schedules for him, just getting him prepared … I would think that it will be helpful that clinics have those visuals for kiddos as well. It just helps them transition better to things coming up, especially kids that have delays and need a little bit more help in understanding.” (interviewee 12)

5.3 Continuity of provider/care

“I think the main thing is just having the same staff work with him every time, because I think that they know what to expect” (interviewee 20)

“But what we've done is we've come enough and had the same dentist over and over, calm demeanor and desensitized him. So now he'll go in without crying and he'll sit in the chair … They go slow and tell them everything they're doing. And now he will hold his mouth open and let them check or brush or floss.” (interviewee 13)

5.4 Provider rapport: Positive attitude

“It was like, ‘I'm going to hang out with my friend [the hygienist] and [the dentist]. They have a big trunk with toys, and we hang out and we listen to music, and then we open my mouth and then we sing some more. Then we open my mouth again, and then we brush.’ I mean, toward the end, they could even use the cleaning machines and flossing.” (interviewee 35)

“And I went in there [a dental office] and you always know when you're working with someone who actually cares … the way he treated us, that was incredible. We had a wonderful experience.” (interviewee 37)

6 DISCUSSION

When comparing the findings of this study to a systematic review published in 2020 titled Barriers in Access to Dental Services Hindering the Treatment of People with Disabilities, there were some similarities.15 Both this study and the 2020 study highlighted the provider's ability and willingness to treat a patient with SHCN as a key barrier to dental care for this population. The major difference between the two studies was that that this study identified enablers and facilitators to accessing dental care, while the 2020 study did not. The facilitators identified in this study can inform future interventions to increase access to care.

An important finding in this study was that on average, children with SHCN complete dental visits less frequently than the recommended periodicity. According to the AAPD, periodicity of dental visits for children at high risk for caries with SHCN should be every 3 months. This study found that dental visits occurred about every 9 months. Prior studies have shown that children who receive dental care with GA are likely to develop future caries, and that more frequent recall visits are associated with less dental disease.16, 17

Another key finding from this study was the fact that on average, families drove 65.8 miles one direction to obtain dental care for their child at UCSF. This finding is supported by other studies that have identified that the healthcare systems capacity to provide dental care to those with SHCN is very low.18 Future initiatives to increase providers, especially in non-urban communities, who accept, are trained, and feel comfortable seeing individuals with SHCN could alleviate some barriers these families face.

Lastly, this study found that 66.4% of the study population returned to UCSF for dental care after their GA appointment. However, this does not indicate that other families did not have a dental home for their child with SHCN. The inability to understand access to dental care at providers other than UCSF is a limitation of this study. For the one-third of patients who never returned for dental visits, these families may have found a new dental home, moved out of the area, or may have sought dental care in some other location.

A strength of this study is the diversity of the SHCN population that was interviewed. Children with different SHCN may have specific challenges when accessing dental care, and this study made a conscious effort to include many different SHCN diagnoses. A large qualitative sample size was used in this study due to the homogeneity of the study population. Since this study was conducted on a specific population that is located in northern California these results may not be generalizable.

7 CONCLUSION

Children with SHCN face many barriers when trying to access routine dental care. Children with SHCN do not always return for routine dental care, follow up and prevention following dental treatment with GA. Child stress/anxiety, finding an accepting provider, dismissive providers, and the proximity of provider contribute to challenges in children with SHCN obtaining dental care. Effective behavior management, continuity of provider/care, positive provider attitude, and referrals to an accepting provider can help mitigate the lack of access to regular dental care that many of these family's face.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to Dr. George Taylor, DMD, MPH, DrPH and Dr. Kristin Hoeft, PhD, MPH for their contribution to the formulation of study design. This study was supported by the University of California San Francisco Population Health and Health Equity Scholars pilot award. This project was also supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) award number K0245715. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.