Metastatic Malignant Phaeochromocytoma in Ascitic Fluid: Cytological Diagnosis of a Rare Entity

Funding: This work was supported by Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland; BRC NIHR Newcastle; BDIAP.

Graphical Abstract

In summary, a review of the literature showed that there are only isolated case reports of ruptured pheochromocytoma and to the best of our knowledge this report is the first to document metastatic phaeochromocytoma in peritoneal fluid within the cytopathology literature. Our case report emphasises the importance of clinical history in the context of the cytopathologic evaluation, and good cell block preparation, which allows the use of IHCs in challenging cases as it may lead to the discovery of unusual metastatic sources.

1 Introduction

Phaeochromocytomas are rare neuroendocrine neoplasms originating from chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, which are responsible for catecholamine production [1]. These tumours are part of the spectrum of paragangliomas when arising extra-adrenally. They have a 5%–15% [2-4] lifelong risk of metastasis to bone, lung, liver, and lymph nodes [5]. Malignancy according to the World Health Organization (WHO) is based on metastatic potential rather than histologic criteria. There is no single histologic feature that can predict metastatic risk; various multi-parameter scoring systems (e.g., Phaeochromocytoma of the Adrenal Gland Scaled Score (PASS), Grading of Adrenal Phaeochromocytoma and Paraganglioma (GAPP), and Composite Phaeochromocytoma/Paraganglioma Prognostic Score (COPPS) [6-8]) have been proposed [9]. Adverse histological findings include high proliferative fraction, comedonecrosis, diffuse growth pattern, and high cellularity.

Phaeochromocytomas exhibit significant molecular heterogeneity, and specific genetic mutations are associated with an increased risk of metastatic disease [10]. Succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit B (SDHB) germline mutations are strongly associated with malignancy, particularly with metastatic potential [11]. Somatic mutations in ATRX and SETD2, high total somatic mutation burden, MAML3 fusions, WNT-altered pathway, and TERT activation have all been associated with an increased risk of metastatic disease [10].

In addition to molecular and histologic findings, clinical parameters such as tumour size (> 5 cm) and biochemical activity (catecholamine hypersecretion) may also indicate aggressive behaviour. In this report, we present a case of metastatic phaeochromocytoma and specifically discuss the cytopathologic features of tumour involving peritoneal fluid.

2 Case Presentation

Clinical histology: We present a case of a 53-year-old woman, who presented to the emergency department with a one-month history of left-sided abdominal/flank pain and 4–5 days of hematuria. Imaging revealed a large complex left kidney mass measuring 11.6 × 9.5 × 9.9 cm. Computed tomography (CT) scan also revealed multiple sub-centimetre nodules in both lung fields that are extremely concerning for metastases. Emergency radical nephrectomy revealed an adrenal-based mass. The patient had no known underlying conditions.

Histopathology: Gross examination showed a 12.3 cm yellow to red, solid adrenal tumour, which effaced the adrenal gland and invaded into the upper to mid-renal pole, renal sinus, and into the periadrenal and perirenal adipose tissue.

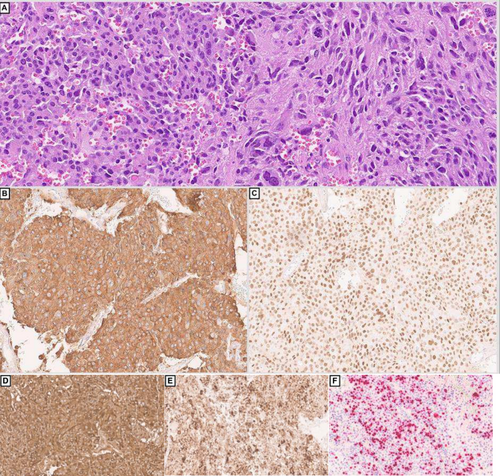

Microscopically, the neoplasm showed a predominantly infiltrative pattern with focal solid sheets, and a minor component with nested architecture. There were multiple areas of lymphovascular invasion. The neoplasm showed a mixture of cells, including markedly pleomorphic bizarre cells (30%), spindle cells (15%) and epithelioid cells (Figure 1A). The tumour showed diffuse staining for the following immunohistochemical (IHC) markers: GATA-3 (Figure 1C), CD56, synaptophysin (Figure 1B), chromogranin, alpha-methylacyl CoA racemase (P504S), and vimentin. Focal/patchy staining was noted for carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9) and S100, while the following are negative: EMA, cytokeratin-903, cam 5.2, AE1/AE3, pancytokeratin, calretinin, inhibin, PAX8, CD10, CK7, CD117, uroplakin II/III, thrombomodulin, p40, p63, Melan A, SOX-10, HMB-45, cathepsin K, desmin, smooth muscle actin(SMA), myogenin, CD99, CD34, ERG, TLE1, STAT6, ALK. The tumour cells demonstrated preserved SDHB and INI expression and showed cytoplasmic beta catenin staining. The KI-67 proliferation index was approximately 40% overall, but hotspot areas reached nearly 80%. The overall features were consistent with a phaeochromocytoma with high-risk features for metastasis. Serum and urine catecholamines were negative. The modified GAPP (M-GAPP) Score of the lesions was high risk 9/10 (Ki-67 index ≥ 3%: 2 points; presence of necrosis: 2 points; vascular or capsular invasion: 1 point; cellularity: 1 point; large tumour size ≥ 5 cm: 1 point; elevated plasma norepinephrine or normetanephrine: 0; and large and irregular cell nests: 1 point).

Molecular analysis showed only a NF1 mutation p. Y2285Tfs*5, with a low tumour mutational burden (1.0 Mutations/Mb).

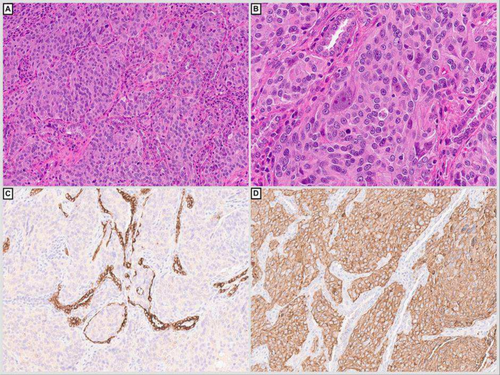

A few months later, a CT scan showed worsening of the bilateral sub-centimetre lung parenchymal nodules, as well as mediastinal, bilateral axillary and subpectoral lymph nodes. Right middle and lower lung lobe wedge resection demonstrated multiple foci of metastatic phaeochromocytoma (Figure 2A–D). The patient was treated with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy.

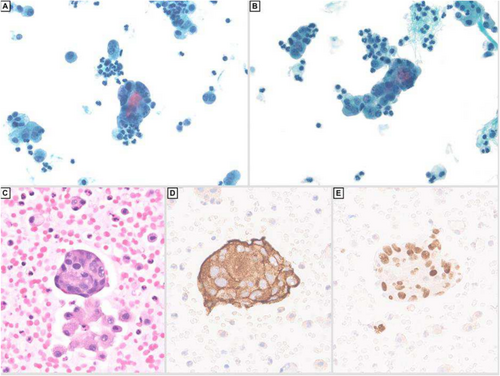

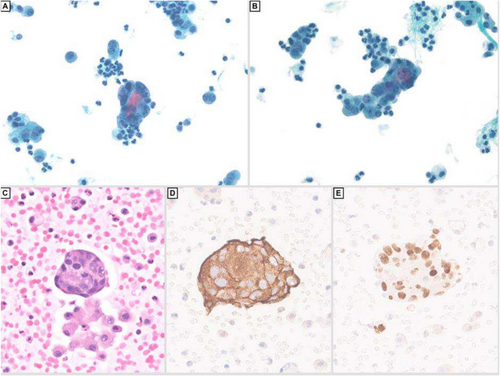

She eventually developed ascites, which was drained and sent to cytology. The fluid showed irregular clusters and single highly pleomorphic cells with increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, irregular nuclear outlines and salt and pepper chromatin (Figure 3A–C). The tumour cells were positive for synaptophysin (Figure 3D) GATA-3 (Figure 3E), focally positive for chromogranin, while negative for calretinin, CA9, BerEP4 and cytokeratin AE1/AE3. These features were compatible with involvement by metastatic phaeochromocytoma. The patient was investigated through imaging, which revealed metastasis of the tumour to the lung, liver, spleen, spine and pelvis. Unfortunately, the patient passed away 1 week after obtaining this ascitic fluid.

3 Discussions

Ascitic fluid involvement by malignant phaeochromocytoma is rare. Typically, malignant phaeochromocytomas metastasise to lymph nodes, bones, lungs, and liver [5]. There are only a few case reports reporting peritoneal tumour spread or implantation [12-15]. They mainly describe disruption of the tumour during biopsy [16] or surgical intervention, and subsequent seeding into the abdominal cavity [17]. In contrast, our case presents at an advanced stage at initial diagnosis with no tumour disruption during surgery. The M-GAPP scoring system evaluates several histologic criteria and provides a cumulative score that categorises tumours into groups with increasing metastatic potential [2]. The primary tumour in our case has a high risk for metastasis, based on this scoring system (see above).

The absence of intact architecture and possibility of sampling bias in cytology specimens limit the application of the M-GAPP scoring system. However, it is important to document certain features such as necrosis and presence of mitotic figures. Nonetheless, cytopathologic evaluation remains a valuable diagnostic tool, offering insights that can guide management decisions and provide material for molecular studies, especially in inoperable cases. Careful review of clinical and imaging findings is paramount in the evaluation of serous fluid specimens to ensure that certain entities and primary sites are not missed. This is important in uncommon malignancies such as a phaeochromocytoma, which can be mistaken for a neuroendocrine tumour or carcinoma, and other epithelial malignancies. By IHC, adenocarcinomas, neuroendocrine tumours and neuroendocrine carcinomas would express epithelial markers, while phaeochromocytoma would express neuroendocrine markers with negative epithelial markers. Cytology-histology correlation, and a focused panel of IHCs can help with confirming the diagnosis and ruling out other considerations.

4 Conclusions

In summary, a review of the literature showed that there are only isolated case reports of ruptured pheochromocytoma, and to the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to document metastatic phaeochromocytoma in peritoneal fluid within the cytopathology literature It emphasises the importance of clinical history in the context of the cytopathologic evaluation and good cell block preparation, which allows the use of IHCs in challenging cases as it may lead to the discovery of unusual metastatic sources.

Author Contributions

Scarlet Brockmoeller: manuscript preparation and review, diagnosis of the case, concept, literature search and editing. Sigfred Lajara: figure preparation, editing and review of manuscript. Samer Khader: diagnosis of the case, concept, manuscript review, figure preparation and editing.

Acknowledgements

Scarlet Brockmoeller: BDIAP Innovation Grant Report for the support of a Cytology Placement at Department of Cytology, UPMC, University of Pittsburgh, The Pathological Society of Great Britaina & Ireland (118650) and Scarlet Brockmoeller is further supported by the NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The NIHR Newcastle BRC is a partnership between Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle University and Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). Dr Brockmoeller is supported by the NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.