Myocardial considerations in type 2 diabetes: 2018

2型糖尿病患者的心肌问题:2018年

Heart failure (HF) continues to be one of the biggest public health problems in the 21st century, affecting 5.7 million adults in the US and accounting for one in nine deaths. Half of those developing HF die within 5 years of diagnosis. The cost associated with HF (i.e. for healthcare services, medications, and missed days of work) is estimated to be US$30 billion dollars per year.1 The leading causes of HF continue to be coronary heart disease (the most common), hypertension, and diabetes.2

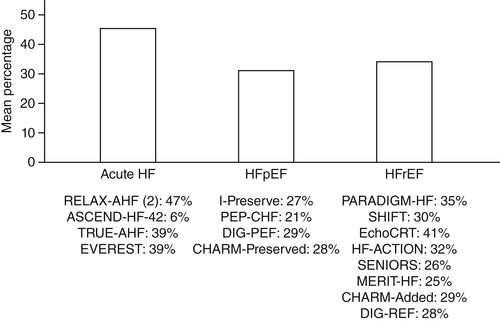

In recent years, increasing numbers of patients with diabetes developing shortness of breath have been found to have left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction. This is found in approximately 28% of asymptomatic and 81% of symptomatic patients with HF and is referred to as HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Currently, there is no good treatment for HFpEF, with a number of failed trials.3 Moreover, recent landmark HF trials had only a low prevalence of diabetes patients (see Fig. 1).

Bursi et al.5 prospectively evaluated 556 patients from Olmsted County (MN, USA) using echocardiograms, finding that 44% of patients in that community had isolated LV diastolic dysfunction. At 6 months, mortality was 16% for both preserved and reduced ejection fraction (EF; age- and sex-adjusted hazard ratio 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.61–1.19; P = 0.33 for preserved vs reduced EF).5

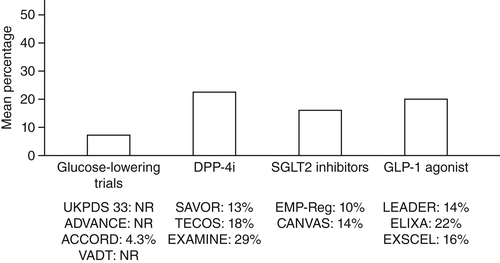

In summary, HF is found and well recognized in diabetes patients. It is also frequently reported as diastolic dysfunction with normal EF, commonly found in hypertensive patients with diabetes. In a recently published HF position paper,4 in current type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) trials the prevalence of HF is approximately 20% (Fig. 2). Moreover, the prevalence of T2DM in HF trials is approximately 35%.4 There have been numerous HF trials completed, but only three major trials found a significant increase in adjusted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (Table 1).

| HFrEF | Drug | HR for significant increase in adjusted all-cause mortality in T2DM | HR for significant increase in adjusted CV mortality in T2DM |

|---|---|---|---|

| PARADIGM-HF | Sacubitril/valsartan | 1.4 | 1.54 |

| Echo-CRT | CRT | 2.08 | 1.79 |

| SOLVD | Enalapril | 1.29 | NA |

- HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; PARADIGM-HF; Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure; Echo-CRT, echocardiography guided cardiac resynchronization therapy; SOLVD, Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; HR, hazard ratio; T2DM, Type 2 diabetes mellitus; CV, cardiovascular.

Matrix matters and insulin resistance

Patients with diabetes frequently have associated hypertension. In recent large prospective randomized cardiovascular safety trials, such as SAVOR (Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with Diabeted Mellitus),6 EXAMINE (EXamination of cArdiovascular outcoMes with alogliptIN versus standard carE),7 TECOS (Trial EvaluatingCardivascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin),8 and EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes),9 hypertension was present in approximately 80% of study patients. A prospective cohort study in the US reported that, compared with normotensive patients, T2DM was almost 2.5-fold more likely to develop in subjects with hypertension.10 Similarly, people with diabetes have an increased risk of developing hypertension.11

Important research in diabetes found that one of the leading causes of hypertension in diabetes patients originates from a greater volume of exchangeable sodium due to hyperglycemia. Feldt-Rasmussen et al.12 reported that, in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients, the exchangeable sodium was approximately 2800–3000 mEq/1.73 m. This was approximately 10% higher than in healthy, normal, non-diabetic control patients, without significant differences in circulating plasma volume. The exchangeable sodium mass was positively correlated with mean arterial pressure. Elevated levels of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) may increase reabsorption of both glucose and sodium, suggesting another important benefit to the use of SGLT2 inhibitors.12-14

Insulin resistance has long been associated with hypertension, which can lead to end organ vascular (LV hypertrophy) damage associated with cardiovascular events. Moreover, many of these hypertensive diabetes patients have myocardial fibrosis (LV hypertrophy by echocardiography) with a consequent stiff, poorly compliant left ventricle, which causes diastolic dysfunction.15 Part of the risk of HF is due to myocardial fibrosis involving increased deposition of inflexible collagen, with thickening of small coronary vessels and the basement membrane.16 In the setting of elevated insulin and glucose levels, the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous system activate the transforming growth factor-β1 pathway, dysregulating extracellular matrix degradation.17

In summary, insulin-resistant patients usually have activation of the RAAS. In addition, sodium and water retention progressing to higher mean blood pressures lead to increased myocardial matrix stiffness, increasing the risk of HFpEF in most diabetes patients. Moreover, a systematic analysis of 65 studies showed evidence of association of both blood pressure and diabetes with arterial pulse wave velocity, a measure of arterial stiffness, further suggesting a role for increased myocardial matrix stiffness in hypertensive diabetes patients.18

Cardiomyocyte and power

Ischemic coronary artery disease is one of the most important causes of HF with reduced EF. However, patients with diabetes and a normal EF can present at a younger age with shortness of breath, but without evidence of coronary disease. Cellular fuel source abnormalities have been found to be another cause of diastolic dysfunction in this setting.

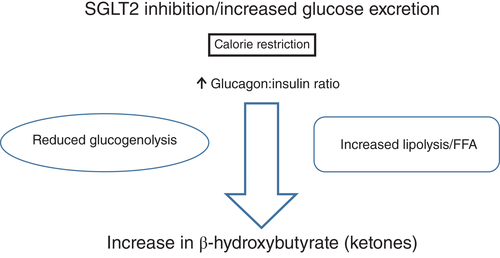

Increased free radicals with inflammation, endothelial cell dysfunction, and other metabolic abnormalities are common in diabetes patients. Cardiomyocyte fuel sources continue to be glucose and free fatty acids (FFAs). The balance between these two well-known fuel sources is affected in patients with diabetes. Activation of lipolysis increases FFA levels as a fuel source, leading to ketogenesis during the fasting state but, during the fed state, glucose is converted to glycogen with an increase in muscle glycogen. Recently, Ferrannini and DeFronzo suggested the potential of ketones as a “superfuel”.19 This originates, in part, from Veech,20 who advocated ketone bodies as “superfuel” for their superiority over glucose or FFAs in safeguarding efficient cardiac metabolism (Fig. 3).20 Frequently overlooked in diabetes HF are abnormalities seen in calcium metabolism. Multiple defects in transporters (e.g. troponin C, plasma Ca2+ pump, sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, myofilament sensitivity) impair ionized calcium handling, increasing the action potential duration and prolonging diastolic relaxation time.21, 22 These abnormalities play key roles in the development of cardiac diastolic dysfunction, adding to the matrix abnormalities discussed previously.

The expression of small non-coding RNA molecules (i.e. microRNAs [miRNAs]) that function in RNA silencing and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression is increased in diabetes, resulting in abnormalities in reactive oxygen species production, calcium handing, autophagy, and matrix formation.23, 24 This may prove to be another mechanism of development of HF in diabetes.

Treatment considerations and conclusions

Heart failure in insulin-resistant (diabetes) patients is complex. Increased wall stiffness and metabolic and molecular protein abnormalities are all involved in the development of HF in diabetes. Aggressive control of known cardiovascular and diabetes risk factors is our best currently available approach, but, unfortunately, many patients do not seek medical attention until they develop these diseases. The process may begin with genetic abnormalities in some people, but continued exposure to excess nutrients with consequent increased metabolic abnormalities must be targeted early in life. The American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) guideline25 suggest diuretics as the initial treatment of HFpEF for symptomatic patients. Recently, the American Diabetes Association26 has suggested screening for T2DM in an effort to prevent the development of ischemic heart disease. However, it is sobering to observe that the Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetes Trial did not find nuclear imaging helpful in improving cardiac event rates.27 However, evidence is strong for revascularization (coronary artery bypass grafting–left internal mammary artery or percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]) for reducing cardiovascular events and improving survival in diabetes patients with asymptomatic ischemia.

Heart failure with reduced EF in diabetes is significantly related to myocardial ischemia, whether silent or symptomatic. Nuclear testing or fractional flow reserve in the catheterization laboratory can answer the question whether these patients are having physiologic myocardial ischemia. Furthermore, asymptomatic patients with diabetes and silent myocardial ischemia are in many ways at the highest risk of an adverse outcome. In a study of 1126 asymptomatic patients, the presence of ≥10% ischemia by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was independently associated with death or myocardial infarction (MI) over a median follow-up of 6.9 years (hazard ratio [HR] 2.67; 95% CI 1.31–5.44; P = 0.007).28 Hachamovitch et al.29 studied 10 627 patients with quantitative stress SPECT, with early revascularization in 671. In that study, the mean 1.9-year cardiac mortality rate in non-revascularized patients increased from 0.7% in those with no ischemia to 6.7% in those with >20% ischemia.29

In an Italian study of 2835 patients, the presence of ischemia was a strong independent predictor of mortality in patients with diabetes (HR 1.71; 95% CI 1.34–2.18; P < 0.0001).30 Revascularization by PCI is beneficial by identification of hemodynamically significant flow-limiting lesions during hyperemia with adenosine in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) has been correlated with death and MI in medically treated patients. In a collaborative meta-analysis, the rates of death or MI and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were inversely related to FFR at a median follow-up of 16 months.31

In addition, the 2017 AHA/ACC guidelines suggest the use of biomarker testing with N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) useful for establishing prognosis or disease severity in chronic HF.25 Pharmacologic treatment of HF with normal EF from the current guidelines recommends global risk reduction and the use of diuretics for symptomatic relief.27 Recent exciting data from two SGLT2 inhibitor trials, namely EMPA-REG OUTCOME with empagliflozin and CANVAS32 with canagliflozin, could revolutionize the treatment of HF in diabetes, but further studies are necessary.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the editorial assistance provided by Nicole L. Meyer (Janey and Dolph Briscoe Division of Cardiology, UT Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA).

Disclosure

None declared.

心力衰竭(Heart failure,HF)目前仍然是21世纪最大的公共健康问题之一, 有570万名美国成年人受累, 在每9名死亡的患者中就有1名死于HF。在HF患者中有一半的人在诊断后的5年内就会死亡。据估计与HF相关的成本(即医疗保健服务、治疗药物以及失去工作的时间)每年都达到了300亿美元1。HF的主要病因仍然是冠心病(最常见)、高血压以及糖尿病2。

近年来, 越来越多出现呼吸急促的糖尿病患者被发现合并有左心室(LV)舒张功能障碍。在大约28%无症状以及81%有症状的HF患者中可发现合并有左心室舒张功能障碍, 被称为保持射血分数的HF(HF with preserved ejection fraction,HFpEF)。目前, 针对HFpEF还没有很好的治疗方法, 只有一些失败的试验3。此外, 最近针对HF的里程碑式试验只研究了较低比例的糖尿病患者(图1)。

Bursi等5使用超声心动图前瞻性地对556名来自Olmsted County县(MN, USA)的患者进行了评估, 发现在该社区中有44%的患者都单独合并LV舒张功能不全。第6个月时, 在保持射血分数(EF)以及射血分数下降的患者中总死亡率为16%(保持EF与EF下降的患者相比, 年龄与性别校正之后的危险比为0.85;95%置信区间[CI]为0.61-1.19;P=0.33)5。

总之, 在糖尿病患者中可以发现HF,目前人们已经很好地认识到了这一点。它也经常被报告为舒张功能障碍合并正常EF,常见于合并高血压的糖尿病患者。在最近发表的HF立场声明文件中4,目前2型糖尿病(T2DM)试验中的HF患病率大约为20%(图2)。此外, 在HF试验中T2DM的患病率大约为35%4。目前已经完成了许多HF试验, 但是只有3项主要试验发现糖尿病患者校正后的全因以及心血管死亡率显著增加(表1)。

基质问题与胰岛素抵抗

糖尿病患者经常合并高血压。在最近大型的前瞻性随机心血管安全性试验中, 例如SAVOR(Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with Diabeted Mellitus,糖尿病患者使用沙格列汀治疗后的血管结果记录评估)6、EXAMINE(EXamination of cArdiovascular outcoMes with alogliptIN versus standard carE,使用阿格列汀或者标准治疗后的心血管结果调查)7、TECOS(Trial EvaluatingCardivascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin,评估西格列汀治疗后心血管结果试验)8、以及EMPA-REG OUTCOME(Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes,2型糖尿病患者使用恩格列净治疗后的心血管结果以及死亡率)9,在研究的患者中大约有80%的人存在高血压。据美国一项前瞻性队列研究报告, 与血压正常的患者相比, 合并高血压的受试者发生T2DM的可能性几乎要高2.5倍10。同样, 合并糖尿病的患者出现高血压的风险也增加了11。

既往关于糖尿病的重要研究中发现, 糖尿病患者出现高血压的主要原因之一就是因为高血糖带来了大量可交换钠最终导致了血压升高。据Feldt-Rasmussen等12报告, 在1型糖尿病患者中, 可交换钠大约为2800–3000 mEq/1.73 m。与健康、正常、非糖尿病对照组患者相比大约要高10%,但是循环中的血浆容量却无显著性差异。可交换钠数量与平均动脉压之间呈正相关。高水平的钠-葡萄糖共转运体-2(SGLT2)可以增加葡萄糖与钠的重吸收, 这意味着使用SGLT2抑制剂治疗具有额外的显著获益12-14。

胰岛素抵抗长期以来都与高血压相关, 这可能导致与心血管事件相关的终末器官血管(LV肥大)损害。此外, 在高血压合并糖尿病的患者中有很多人都出现了心肌纤维化(超声心动图提示LV肥厚),随后就出现了心肌僵硬, 左心室顺应性差导致舒张功能障碍15。HF的部分风险是由于心肌纤维化, 包括硬性胶原沉积增加、小冠状血管以及血管基底膜加厚16。在胰岛素与葡萄糖水平都升高的环境中, 肾素-血管紧张素-醛固酮系统(renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system,RAAS)与交感神经系统会激活转化生长因子-β1通路, 导致细胞外基质降解失调17。

总之, 胰岛素抵抗患者通常都会激活RAAS。另外, 水钠潴留进展到更高的平均血压后, 可导致心肌基质硬度增加, 在大部分的糖尿病患者中都会导致HFpEF的风险增加。此外, 对65项研究进行系统分析后发现, 血压以及糖尿病与动脉脉搏波速度、动脉僵硬度测量结果之间都有相关性的证据, 这进一步表明了在合并高血压的糖尿病患者中心肌基质硬度增加的影响18。

心肌细胞与能量

缺血性冠状动脉疾病是HF合并EF下降最重要的病因之一。然而,EF正常的低龄糖尿病患者也会出现呼吸急促, 但是却没有冠状动脉疾病的证据, 目前已经发现在这种环境下细胞能量源异常是另外一个可导致舒张功能障碍的原因。

在糖尿病患者中经常能够见到伴随炎症而增加的自由基、内皮细胞功能障碍以及其他代谢异常。心肌细胞的能量源一直都是葡萄糖与游离脂肪酸(FFAs)。在糖尿病患者中, 这两种众所周知能量源之间的平衡受到了影响。激活脂解作用后升高的FFA水平可作为一种能量源, 导致在空腹状态期间生成了酮体, 但是在进食状态下, 葡萄糖被转化为糖原, 同时肌糖原也在增加。最近,Ferrannini与DeFronzo建议可将酮类当做潜在的“超级能量”19。这有一部分是源自Veech20的观点, 他主张将酮体作为“超级能量”, 因为酮体在保障有效心脏代谢方面优于葡萄糖与FFA(图3)20。在合并糖尿病的HF患者中经常被忽视的是钙代谢异常。多种转运蛋白都有缺陷(例如肌钙蛋白C、血浆Ca2+泵、肌膜上的Na+/Ca2+交换器、肌丝敏感性),这些都会导致离子钙处理受损, 增加动作电位持续时间并且延长舒张期弛豫时间21,22。这些异常在心脏舒张功能障碍的发生过程中有着关键的作用, 可作为先前讨论的基质异常的补充。

在糖尿病患者中, 小的非编码RNA分子(亦即microRNAs)的表达增加, 其功能是使得RNA保持沉默以及转录后调控基因的表达, 这导致活性氧的产生、钙处理、自我吞噬以及基质的形成都出现了异常23,24。这很可能是糖尿病患者发生HF的另一种机制。

治疗需要考虑的问题以及结论

胰岛素抵抗(糖尿病)患者出现心力衰竭的原因很复杂。心室壁硬度增加以及代谢与分子蛋白异常都与糖尿病患者发生HF有关。我们目前可用的最好方法就是积极控制已知的心血管以及糖尿病危险因素, 但是, 不幸的是, 许多患者在发生这些疾病之前都不去就医。这一过程在某些人中可能始于遗传异常, 但是若持续暴露于过量的营养物质环境中, 随后增加的代谢异常就必须在生命的早期就得到控制。据美国心脏协会(AHA)/美国心脏病学协会(ACC)指南25建议, 有症状的HFpEF患者的初始治疗可选择利尿剂。最近, 美国糖尿病协会26为了预防缺血性心脏病的发生建议对T2DM患者进行筛查。然而, 我们要清醒地看到, 在无症状的糖尿病患者中检测缺血的试验(Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetes Trial)中, 没有发现核成像有助于改善心脏事件发生率27。然而, 有强力证据表明, 对于合并无症状缺血的糖尿病患者来说, 血运重建(冠状动脉旁路移植术-左乳内动脉或经皮冠状动脉介入治疗[percutaneous coronary intervention,PCI])能够减少心血管事件并且提高生存率。

在糖尿病患者中合并EF下降的心力衰竭与心肌缺血显著相关, 无论是静默型还是有症状型心肌缺血。核素试验或者在导管实验室中检测到的分数流量储备可以回答这个问题, 亦即这些患者生理上是否存在心肌缺血的问题。此外, 合并糖尿病与静默型心肌缺血的无症状患者在许多方面都存在发生不良结果的最高风险。在一项纳入了1126名无症状患者的研究中, 经过中位数为6.9年的随访, 使用单光子发射计算机断层扫描(SPECT)检查后发现, 存在≤10%的缺血与死亡或者心肌梗死(MI)独立相关(危险比[HR]为2.67;95% CI为1.31-5.44;P=0.007)28。Hachamovitch等29使用定量负荷SPECT对10627名患者进行了研究, 其中671名患者进行了早期血管重建术。在该研究中, 非血管重建患者平均随访1.9年的心脏病死亡率从无缺血患者的0.7%增加到缺血> 20%患者的6.7%29。

在意大利的一项纳入了2835名患者的研究中, 存在缺血是糖尿病患者死亡率升高的一个高效的独立预测因子(HR为1.71;95% CI为1.34-2.18;P<0.0001)30。通过PCI手术进行血运重建是有益的, 因为在心导管检查实验室中在使用腺苷后的充血期间通过血流动力学可以鉴定出现显著限流的病变部位。在接受医学治疗的患者中血流储备分数一直都与死亡以及MI相关。在一项通力协作的meta分析中, 发现在中位数为16个月的随访中死亡率或者MI发病率以及主要不良心脏事件都与FFR呈负相关31。

另外, 为了明确慢性HF的预后以及疾病严重程度,2017年AHA/ACC指南建议使用N-末端B型尿钠肽原作为生物标志物检测因子25。从目前指南推荐的可以减少系统风险的药物中选择药物来治疗EF正常的HF,并且使用利尿剂来缓解症状27。最近令人振奋的数据来自于两项SGLT2抑制剂试验, 亦即使用恩格列净治疗的EMPA-REG OUTCOME试验以及使用坎格列净治疗的CANVAS32试验, 它们彻底改变了合并HF的糖尿病治疗方法, 但是仍然需要进行进一步的研究。

图1 在筛选过的心力衰竭(HF)试验中2型糖尿病(T2DM)的百分比。在针对急性HR、保持射血分数的HF(HFpEF)以及射血分数下降的HF(HFrEF)使用抗HF药物的主要结果试验中, 只纳入了少数几名T2DM患者。图中显示了各组中的糖尿病患者平均百分比。RELAX-AHF,Serelaxin和重组人松弛素-2治疗急性心力衰竭;ASCEND-HF,奈西立肽治疗失代偿性心力衰竭的临床疗效研究;TRUE-AHF,在急性心力衰竭中乌拉立肽的有效性与安全性试验;EVEREST,在使用托伐普坦治疗心力衰竭的结果研究中加压素拮抗作用的疗效;IPreserve,厄贝沙坦在保持收缩功能心力衰竭中的应用;PEP-CHF,培哚普利在老年慢性心力衰竭患者中的应用;DIG-PEF,调查洋地黄在保持射血分数心力衰竭中的作用;CHARM-Preserved,评估坎地沙坦在心力衰竭中如何降低死亡率与发病率;PARADIGM-HF,在心力衰竭试验中比较ARNI与ACEI对全球死亡率以及发病率影响的前瞻性试验;SHIFT,IF抑制剂伊伐布雷定治疗收缩期心力衰竭试验;EchoCRT,超声心动图引导心脏再同步化治疗;HF-ACTION,心力衰竭:一项调查运动训练结果的对照试验;SENIORS,药物洗脱支架在老年冠心病患者中的应用;MERIT-HF,充血性心力衰竭患者使用美托洛尔CR/XL治疗的随机干预试验;CHARM-Added,坎地沙坦在心力衰竭中的应用:评估死亡率与发病率的下降情况;DIG-REF,调查洋地黄在射血分数下降心力衰竭中的作用(改编的插图来源于Seferovíc等4的研究)。

图2 在筛选过的2型糖尿病试验中心力衰竭(HF)患者的百分比。在使用新型抗糖尿病药物的主要结果试验中, 只纳入了少数几名HF患者, 新型抗糖尿病药物包括降糖药、二肽基肽酶-4抑制剂(DPP4I)、钠-葡萄糖共转运体2(SGLT2)抑制剂以及胰高血糖素样肽-1(GLP-1)激动剂。合并HF的患者平均比例显示在各组中。NR,没有记录;UKPDS 33:英国前瞻性糖尿病研究;ADVANCE,糖尿病与血管疾病行动研究:百普乐与达美康缓释片对照评估试验;ACCORD,控制糖尿病心血管风险行动研究;VADT,美国退伍军人糖尿病试验;SAVOR,糖尿病患者使用沙格列汀治疗后的血管结果记录评估;TECOS,评估西格列汀治疗后心血管结果试验;EXAMINE,使用阿格列汀或者标准治疗后的心血管结果调查;EMP-Reg,2型糖尿病患者使用恩格列净治疗后的心血管结果以及死亡率;CANVAS,评估坎格列净心血管结果研究;LEADER,利拉鲁肽对糖尿病患者的疗效与作用:心血管预后结果评估;ELIXA,在急性冠脉综合征中评估利西那肽的疗效;EXSCEL,艾塞那肽减少心血管事件研究(改编的插图来源于Seferovíc人4的研究)。

图3 SGLT2抑制剂的潜在益处。SGLT2抑制剂可以通过提高葡萄糖水平和降低胰岛素:葡萄糖比值来提高肝脏中酮体(3-羟基丁酸、乙酰乙酸和丙酮)的生成。此外Veech20显示, 与心脏单独代谢葡萄糖相比, 在心脏中的酮体代谢可升高28%的效率的根本原因是D-β-羟基丁酸酯中的燃烧热本身比丙酮酸(线粒体底物, 糖酵解的终产物)更高。FFA,游离脂肪酸

表1 在心力衰竭试验中的全因死亡率:聚焦于2型糖尿病

| HFrEF | 药物 | HR显著增加T2DM患者校正后的全因死亡率 | HR显著增加T2DM患者校正后的CV死亡率 |

| PARADIGM-HF | 沙卡布曲/缬沙坦 | 1.4 | 1.54 |

| Echo-CRT | CRT | 2.08 | 1.79 |

| SOLVD | 依那普利 | 1.29 | NA |

HFrEF,射血分数下降的心力衰竭;PARADIGM-HF,在心力衰竭试验中比较ARNI与ACEI对全球死亡率以及发病率影响的前瞻性试验;Echo-CRT,超声心动图引导心脏再同步化治疗;SOLVD,左室功能不全研究;CRT,心脏再同步治疗;HR,危险比;T2DM,2型糖尿病;CV,心血管。