Isolated leukemia cutis as extramedullary relapse of acute myeloid leukemia

Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) arises from clonal expansion of malignant hematopoietic precursor cells in the bone marrow. In rare instances, AML can recur with prominent extramedullary manifestations (i.e., leukemia cutis or myeloid sarcoma), either simultaneously or preceding marrow involvement, or as a sole site of primary disease relapse.

1 INTRODUCTION

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clonal neoplasm of the bone marrow and blood where hematopoietic stem cell precursors of the myeloid lineage acquire various genetic mutations and undergo unregulated proliferation. AML can be classified as favorable risk (e.g., RUNX1-RUNX1T1, CBFB-MYH11, mutated NPM1 without FLT3-ITD or with FLT3-ITDlow b, or biallelic mutated CEBPA), intermediate risk (e.g., mutated NPM1 and FLT3-ITDhigh b, wild-type NPM1 without FLT3-ITD or with FLT3-ITDlow b, or MLLT3-KMT2Ac), or adverse risk (e.g., DEK-NUP214, KMT2A rearranged, BCR-ABL1, del(5q), abnormal(17p), monosomal karyotype, or wild-type NPM1 and FLT3-ITDhigh b) based on cytogenetic profiles.1 Previously, the standard chemotherapy regimen of daunorubicin and cytarabine led to a five-year survival rate of 40–45% in patients 50–55 years of age, and less than 10–15% in patients 60 years of age and older.2

Older patients tend to have higher risk cytogenetics, with one study demonstrating more involvement of chromosomes 5, 7, and 17.3 In addition, when stratified by risk category, patients younger than age 56 have increased overall survival compared with older patients.3 Currently, there is no standard approach to the treatment of AML in older populations. Occasionally, patients have extramedullary manifestations, such as leukemia cutis and myeloid sarcoma.4 Appropriate therapy depends on the characteristics of each specific acute leukemia, patient characteristics, and goals of care.1 Traditionally, induction therapy consists of high-dose chemotherapy. However, recent phase 1b trial data have demonstrated high rates of complete remission (CR) and long-term overall survival following the combination of small-molecule BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax and hypomethylating agents (HMA) azacitidine or decitabine in older patients with newly diagnosed AML.5 Venetoclax combined with an HMA has been adopted as an effective, safe alternative for patients with contraindications to intensive induction chemotherapy.5

2 CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old woman was diagnosed with intermediate/high-risk AML after presenting to the emergency department with fatigue and a white blood cell count of 131,300/μl (normal range 3500–10,500/μl) with 80% blasts in her peripheral blood. Medical history was significant for diastolic heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, pericarditis with effusion, obstructive sleep apnea, major depressive disorder, anxiety, and remote tobacco use. Family history was significant for colorectal cancer in her mother, father, siblings, and grandmother.

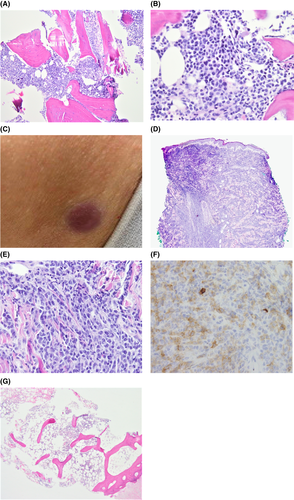

A bone marrow biopsy (BMB) confirmed AML with a hypercellular marrow (90% cellularity) with markedly diminished hematopoiesis and 97% blasts (Figure 1A,B). The patient's original monoblastic leukemia (AML) demonstrated blasts that expressed dim to negative CD45, CD33, CD15 (subset), HLA-DR, CD117, dim CD13 (subset), CD11c, CD117, CD64, CD38, and CD56 (subset). The blasts were negative for CD19, CD3, and mostly negative for CD34. Cytogenetics showed a t(9;11)(p21.3;q23.3); MLLT3-KMT2A mutation and NeoTYPE® Myeloid Disorders Profile showed a PTPN11 mutation, significant for intermediate/high-risk AML.

She was initially treated with hydroxyurea for cytoreduction but developed new altered mentation and word-finding difficulty necessitating urgent leukapheresis. Subsequently she started azacitidine and venetoclax chemotherapy with post-cycle one BMB demonstrating minimal residual disease (MRD) negative CR. She then completed four cycles of azacitidine and venetoclax with a repeat BMB after cycle four demonstrating normocellular bone marrow for age (approximately 25% cellular) with trilineage hematopoiesis and no morphologic evidence of relapsed or residual leukemia. While the patient was undergoing this regimen, she was being evaluated and assessed for a future allogeneic stem cell transplant.

At a follow-up clinic visit, physical exam was concerning for new pink to violaceous nodules on her abdomen and back for which she had urgent dermatological evaluation (Figure 1C). Punch biopsy revealed a diffuse atypical infiltrate of immature hematopoietic cells (blasts) involving the dermis and underlying subcutaneous adipose tissue, confirming a diagnosis of leukemia cutis (Figures 1D–F). This punch biopsy was done 14 days after her post-cycle four BMB, which had shown her to be in an MRD-negative CR. A repeat BMB, three weeks after the prior one, was without morphological evidence of relapsed leukemia (Figure 1G). MRD assessment was negative, but next-generation sequencing demonstrated a new low-level KMT2A rearrangement.

Within one month of her leukemia cutis diagnosis, she developed multiple medical complications and chose to pursue comfort care measures. Ultimately, she passed one month following her diagnosis of leukemia cutis.

3 DISCUSSION

Leukemia cutis is rare, with the exact incidence and demographics unknown.6 It occurs when leukemic cells directly invade the epidermis, dermis, or subcutis.7 Clinically, the lesions tend to present as papules and nodules and are most frequently located on the trunk and extremities.8 Leukemia cutis is most commonly seen in AML (prevalence of approximately 13%) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).6 It may present prior to the development of leukemia in the peripheral blood and/or bone marrow (2%–3% of cases), concurrently with the presentation of systemic leukemia (23%–44%), or following a leukemia diagnosis (55%–77%).6 Evaluation of leukemia cutis includes obtaining a complete blood count and peripheral smear, BMB with immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, flow cytometry studies, a skin biopsy, and immunophenotyping.6 Following a skin biopsy-proven diagnosis of leukemia cutis, systemic manifestations can take anywhere from three weeks to 20 months to develop.9

The prognosis for patients with leukemia cutis is considered poor. A retrospective study examining patients between 2005 to 2007 found AML patients with leukemia cutis were 2.06 times more likely to die of leukemia, 1.66 times more likely to die of all causes, and had a worse five-year survival in comparison with AML patients without leukemia cutis.10 Another recent retrospective review observing patients with leukemia between 2012 and 2021 concluded that 84% of patients diagnosed with leukemia cutis ultimately died.11 Of the patients who died, 93% died within 10 months of their diagnosis of leukemia cutis.11 These findings are consistent with our patient who died within one month of her diagnosis.

A standardized treatment plan specifically for leukemia cutis does not exist, with current approaches focusing on utilizing systemic therapy (Table 1), such that even patients with leukemia cutis and a negative BMB are typically managed with intensive AML chemotherapy.12 Those with a BMB suggestive of AML are managed with intensive AML chemotherapy and considered for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation as consolidation.12 One study investigated the diagnostic utility and safety of AML patients receiving skin punch biopsies during inpatient chemotherapy treatment.13 After reviewing 37 biopsies, the authors noted minimal complications and found the biopsy results to be useful in guiding therapy.13 Total skin electron beam therapy can also be pursued following chemotherapy if leukemia cutis lesions persist and the BMB is negative.12 The skin lesions tend to improve with leukemia remission.6 If all therapies have failed, enrollment in a clinical trial or palliative care may be considered.12 At the time of this writing, there is only one active clinical trial for patients with leukemia cutis (NCT01371981; a randomized phase III trial of bortezomib and sorafenib tosylate is in newly diagnosed AML). In our case, the patient elected comfort care and hospice. However, if treatment had been pursued, we may have considered an HMA per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

| Study | Patient Age (Years) | Leukemia Type | Leukemia Cutis Onset | Treatment | Patient Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donaldson et al. (2019)14 | 50 | FLT3 D835 mutation-positive AML | Following leukemia diagnosis and BMB negative for residual disease | Reinduction therapy with high-dose cytarabine for seven days followed by allogeneic unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplant three months later | No recurrence of cutaneous or systemic leukemia for two years following diagnosis of AML |

| Qiao et al. (2019)15 | 58 | CMML Type 2 with transformation to AML M5 | Concurrent systemic leukemia |

Hydroxyurea (1000 mg orally twice daily d1–10) and decitabine (20 mg/m2 intravenous d1–5, monthly) followed by idarubicin 10 mg intravenous d1–3 and cytarabine 100 mg intravenous every 12 hours d1–7) two weeks later |

Died three months following diagnosis of LC |

| Qiao et al. (2019)15 | 62 | CMML Type 0 with transformation to AML M5 | Concurrent systemic leukemia | Hydroxyurea (1000 mg orally twice daily d1–10) and decitabine (20 mg/m2 intravenous d1–5, monthly) | Died of gastrointestinal bleeding eight months following diagnosis of LC |

| Du et al. (2020)16 | 40 | AML | Aleukemic leukemia cutis | Two cycles of standard induction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic stem cell transplant | Excellent engraftment and disease status with mild anemia for four months following allogeneic transplant |

| Thomas et al. (2020)17 | 34 | Mixed T/B-cell ALL | Concurrent systemic leukemia | Four cycles of hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) chemotherapy followed by haploidentical bone marrow transplant several months later | No recurrence of cutaneous findings for six months following diagnosis of LC |

| Findakly et al. (2020)9 | 50 | History of cured DLBCL, transformation of t-MDS to AML with inv(11)(p15q23) chromosomal aberration present at time of t-MDS diagnosis | First manifestation of transformation of t-MDS to AML, predated hematological manifestation | Palliative care | Died three months following diagnosis of LC |

| Azari-Yaam et al. (2020)18 | 46 | FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutation-positive AML | Aleukemic leukemia cutis | Combination chemotherapy of idarubicin and cytarabine arabinoside and consolidation with high-dose cytarabine arabinoside followed by autologous stem cell transplant therapy | Died nine months following diagnosis of LC |

| Azari-Yaam et al. (2020)18 | 51 | FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutation-positive AML | Aleukemic leukemia cutis | Combination chemotherapy of idarubicin and cytarabine arabinoside and consolidation with high-dose cytarabine arabinoside | Died 76 days following diagnosis of LC |

| Current case (2021) | 67 | AML | Following leukemia diagnosis and BMB negative for residual disease | Palliative care | Died one month following diagnosis of LC |

- Abbreviation: LC, leukemia cutis.

In conclusion, leukemia cutis is an extramedullary manifestation of AML, which carries a poor prognosis. Given the aggressive clinical course of this entity, it may be beneficial to start empiric systemic treatment for AML prior to confirmation of systemic disease via bone marrow biopsy. This case highlights the need for investigation and development of advanced therapeutic options and guidelines for the local and systemic management of patients with leukemia cutis.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

FD, FE, and NMH wrote the initial draft; AR wrote the figure legends; FD, FE, AR, KM, KMM, ARK, WK, PH, and NMH revised the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors report no acknowledgements.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflict of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Projects involving a single case report are not considered research at our institution, and thus, ethics approval was not obtained.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's next of kin to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.