Effective treatment of advanced Hodgkin lymphoma with a modified BEACOPP regimen for a patient with demyelinating hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy type 1 (HMSN1)

Funding information

None

Abstract

Treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) in adults comprises substantial risk of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Here, we describe the case of patient with Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease or HSMN1 and advanced Hodgkin lymphoma undergoing treatment with modified BEACOPP achieving complete remission without major aggravation of neurological symptoms.

1 INTRODUCTION

The therapeutic strategy for Hodgkin lymphoma is designed according to the Ann-Arbor staging classification, additional risk factors and the age of the patient.1 Depending on the country, two main regimens for Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) build the standard (individually or in combination), ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) and BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone). Advantages of the ABVD regimen are the lower toxicities and overall costs. The BEACOPP regimen—originally developed by the German Hodgkin Study Group—provides higher and longer remission rates, but with more side effects and higher toxicities, such as neuropathies, lung damage and secondary acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome (AML/MDS).1 In many parts of the world, BEACOPP is the standard regimen to treat advanced HL followed by optional radiotherapy.2, 3 Chemotherapy-induced toxicity to the lung caused by bleomycin is an important issue in the ongoing development of new treatment strategies.4 However, chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity mainly caused by etoposide, cyclophosphamide and especially vincristine remain a frequently observed side effect of actual treatment strategies.5

The hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN), also known as Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, is characterized by a dysfunction of the myelin sheath causing an innate neuropathic disorder.6 HMSN is caused by mutations in the genes that produce the proteins involved in the structure and function of either the peripheral nerve axon or the myelin sheath. Depending on the localization of the mutation (in chromosome 17 or 1), many forms of HMSN disease may occur, including a demyelinating type HMSN1,7 an axonal type HMSN28 or an intermediate Type.6 HMSN1A is an autosomal dominant disease that results from a duplication of the gene on chromosome 17 that carries the instructions for producing the peripheral myelin protein-22 (PMP-22). The PMP-22 is a membrane protein that is a critical component of the myelin sheath.9 Overexpression of the respective gene disrupts the structure and function of the myelin sheath protein. The most frequent and relevant mutations for HMSN1 are duplications and point mutations in the PMP-22 gene. Further mutations in the MPZ, LITAF, SH3TC2, MTMR2, and GDAP1 genes may also cause HMSN1 but less frequently.10 The consequences of the mutations are shortened myelin sheath11 and a neuropathic disorder characterized by progressive muscle weakness starting on feet and hands, decrease of muscles mass, pes cavus, equine gait, loss of reflexes, painful dysesthesias, and distal sensory loss particularly of the lower limbs.12 The clinical course of the HMSN1 subtype is characterized by a fast progression and a high risk for a non-ambulatory follow-up before the age of 20.13 However, despite the symptoms being frequently manifest during the first or second decade of life, some patients remain free of symptoms and present a cryptic form with mild or even without apparent clinical symptoms.

We report the first case of an effective treatment of a HMSN1 patient with HL and potentially neurotoxic chemotherapeutic regimen with achievement of complete remission and no clinically relevant treatment-related aggravation of neurologic symptoms.

2 CLINICAL CASE

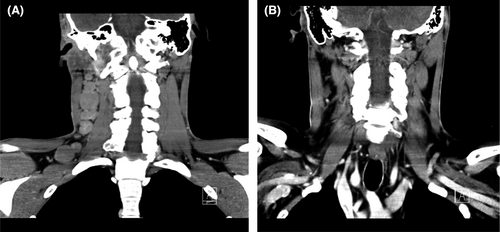

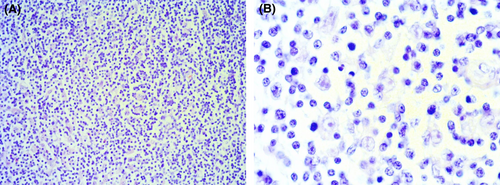

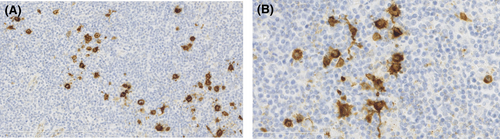

In April 2014, a 30-year-old male patient presented in our outpatient care unit with persistent lymphadenopathy of the right neck for several weeks. In addition, the patient presented B symptoms such as night sweats and weight loss (>10% body weight within 3 months). The patient had, as pre-existing disease, a demyelinating hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN1), characterized by an heterozygous point mutation, c.256C>T, p.Gln86X(p.Q86X) in the PMP22-gene. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed suspicious lymph nodes in the right cervical and supraclavicular region (Figure 1) and in the left jaw angle, consistent with HL. Thorax and abdomen CT imaging did not show evidence of manifestations except for relevant splenomegaly. Cervical lymph node biopsy was carried out and histological analysis revealed an EBV positive mixed cellularity classic Hodgkin lymphoma (Figures 2 and 3). The patient was staged IIIB according to the Ann-Arbor classification. Considering the advanced staging and the increased patient's risk for substantial neurotoxic side effects due to HMSN1, a modified BEACOPP regimen (without vincristine) was used for treatment. The regimen was chosen and modified taken into account the previous published literature, the known neurotoxic effects of the respective substances and the need for treatment of the newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma. The ABVD regimen was not chosen as first-line treatment due to reduced effectiveness of ABVD in the absence of vinblastine in advanced stages of HL and the expected substantially increased toxicity of salvage regimens as, for example, Brentuximab, DHAP followed by high-dose BEAM in HMSN1 patients in case of a relapse. The modified BEACOPP regimen was given with the standard dosages of bleomycin at 10 mg/m2 (Day 8) etoposide at 200 mg/m2 (Day 1–3), doxorubicin at 35 mg/m2 (Day 1), cyclophosphamide at 1250 mg/m2 (Day 1), procarbazine 100 mg/m2 (Day 1–7) and prednisone 40 mg/m2 (Day 1–14). The first cycle of modified BEACOPP was administered in the hematological hospital ward for best control of possible side effects. Since the first cycle was tolerated without any side effects, all subsequent cycles were administered in an outpatient setting. CT scan assessment after two and four cycles revealed a good partial response to the modified BEACOPP regimen. Light neuropathic symptoms described as tingling sensation in the fingers developed after the third therapy cycle. Based on the potential for neurotoxicity of cyclophosphamide and the good response to treatment, the drug was eliminated from the patient's regimen for the three remaining cycles. The tingling symptoms persisted but were manageable with administration of low-dose gabapentin. The modified BEACOPP regimen was completed as scheduled and without additional toxicities or adverse events. The final CT evaluation after 6 cycles of modified BEACOPP detected a residual lymph node (with a diameter of 1.1 cm). An additional PET-CT scan showed no metabolic activity in the lymph node. No additional treatment was initiated and the patient remained in complete remission (CR) during regular clinical follow-up for over 6 years after end of treatment. In addition, the known HMSN1 did not show signs of progression or new symptoms (Table 1).

|

Nerve conduction velocity (before therapy [N. Medianus]) |

Nerve conduction velocity (3 years after therapy [N. Ulnaris]) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Latency | 12.8 ms | 11.6 ms |

| Amplitude | 1.5 mV | 2.5 mV |

| NCV | 14 m/s | 13 m/s |

3 DISCUSSION

Treatment of patients with HMSN and cancer is challenging, and few data are available regarding the oncologic14-21 and neurologic outcome of these patients.14-41 An established therapeutic strategy for patients with hereditary neuropathy with concomitant malignant diseases is not clearly defined. Regarding the literature, only a limited number of cases are described.14-44 Most of the case reports address the role of vincristine and the aggravation of neuropathic features in presence of cryptic or mild HMSN forms. Here, the diagnosis of HMSN was established based on the unsuspected chemotherapy-induced neurological aggravation. The most frequently reported symptoms of neurological deterioration were tetra-paresis, bulbar dysfunction as severe neurotoxic effects and hypesthesia and areflexia leading to substantially impaired quality of life.16, 22, 25, 27, 28, 31, 39, 40

Regarding the oncologic outcome, very few data are available.14-21 Some cases report good oncological responses in the majority of cases of acute leukemic leukemia (ALL) but also after renal tumors and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).14-21 However, clinically relevant and hardly controllable neurological side effects were again frequently observed, induced by the respective chemotherapies containing vincristine.14-21, 44

In our case, facing an already established diagnosis of HMSN1 and previously published literature on chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity in HMSN1, we decided to adapt a BEACOPP regimen to treat a HL patient. The ABVD protocol without vinblastin was considered to be not sufficient to induce long-term remission in advanced Hodgkin disease. Brentuximab was also excluded due to the high rate of neurotoxicity. We modified the standard protocol by eliminating vincristine from the regimen, in order to avoid possible known vincristine-induced neurotoxic side effects. With additional modifications during therapy consisting in the elimination of cyclophosphamide caused by the suspicion of additional neurotoxicity plus the initiation of gabapentin for management of tingling symptoms, we were able to effectively treat the patient's HL using a modified BEACOPP regimen achieving long-lasting CR.

In summary, modified BEACOPP regimen can be a feasible and effective treatment for patients with advanced HL with underlying HMSN1. Intensive clinical monitoring of the neuropathic symptoms is needed, and adjustments to the therapy are required. The patient achieved and remained in CR for a follow-up period of now 6 years in the absence of severe (neurological) side effects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

PPH wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures. MK, KZH, and MT were involved in the patient's diagnosis and treatment and revised the manuscript. MSVF, FH, and BR critically revised the manuscript and were involved in preparing the figures. FB was involved in the patient's diagnosis and treatment, were involved in preparing the figures and critically revised the manuscript. THB was the senior attending physician on the clinical case and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

None.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.