Occupational therapy-based rehabilitation of sciatic nerve pain

Abstract

Sciatica is a severe form of pain caused by compression of the sciatic nerve that radiates from the back toward the hip and outer side of the leg. Conventional treatments for sciatica include pain medication, physical therapy, and surgery in severe cases. However, these approaches can be invasive and costly and may not provide long-term relief. Occupational therapy refers to the intentional and strategic application of various activities associated with daily life, work, education, and leisure to address functional impairments. Focusing on targeted exercises, manual techniques, and ergonomic modifications to alleviate symptoms and improve function, it offers a promising alternative to medical treatments. Occupational therapy interventions for sciatica can reduce pain, increase mobility, and enhance the overall quality of life. As an empowering approach, such techniques aid symptom management and functional independence. This article explores occupational therapy-based assessments, interventions, outcomes, progress tracking, pharmacotherapy, challenges owing to surgical approaches, and devices for sciatic pain rehabilitation, with assessments aimed at improving the overall quality of life for individuals affected by this condition. Future research should focus on developing and validating new assessment tools and outcome measures specific to sciatica, enabling more accurate evaluation and progress monitoring.

Key points

What is already known about this topic?

-

Sciatica is a severe pain that radiates from the back to the hip and outer side of the leg caused by compression of the sciatic nerve. Traditional treatments for sciatica include pain medications, physical therapy, and in severe cases, surgery.

-

These approaches can be invasive, costly, and may not provide long-term relief.

What does this study add?

-

This study highlights the multifaceted nature of sciatic nerve pain, emphasizing the roles of inflammation and neural sensitization alongside traditional compression theories.

-

This study highlights the importance of a comprehensive treatment approach that integrates pharmacotherapy, surgical options, and occupational therapy interventions for effective management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sciatica is a medical condition arising from issues affecting the sciatic nerve, the largest and longest spinal nerve, which originates from the lumbar and sacral plexuses in the human body.1, 2 The sciatic nerve projects from several nerve roots in the lower back, traverses the buttocks, and extends down the back of each leg, terminating just below the knee. The sciatic nerve's extensive path makes it susceptible to various conditions that can cause irritation, compression, or inflammation, leading to the characteristic symptoms of sciatica.3, 4 The most common cause is a herniated or bulging disc in the lower spine, which can exert pressure on the emerging nerve roots.5, 6 However, other potential causes include lumbar spinal stenosis, degenerative disc disease, spondylolisthesis (vertebral slippage), piriformis syndrome (muscle spasm or tightness), pregnancy-related pressure, and injuries or trauma to the lower back or pelvic area, which should not be overlooked. Certain risk factors can predispose individuals to developing sciatica, such as age (30–50 years old being at highest risk), obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, occupations involving heavy lifting or prolonged sitting, and diabetes. These factors can contribute to underlying conditions that ultimately lead to sciatic nerve irritation. The hallmark symptom of sciatica is a shooting, burning, or searing pain that radiates from the lower back or buttock area down the back of one leg.7-9 This pain can extend all the way to the foot and toes, depending on the location of the nerve compression or irritation. Accompanying this radiating pain, individuals may experience numbness or tingling sensations in the affected leg or foot, weakness or difficulty moving the affected limb, and increased discomfort with movements such as coughing, sneezing, or sitting.10-12 Although sciatica typically affects only one side of the body, both legs may be impacted in rare cases. The severity of symptoms can vary widely, ranging from mild discomfort to debilitating pain that significantly impairs daily activities. In severe cases, individuals may experience loss of bladder or bowel control, which requires immediate medical attention as it could indicate a more serious condition called cauda equina syndrome,13, 14 where the nerve roots in the lower spine are severely compressed. It is crucial to recognize that sciatica is not a standalone condition but rather a symptom of an underlying issue affecting the sciatic nerve.15 Proper diagnosis and treatment of the root cause are essential for effective management and relief of the associated symptoms.16 Conventional strategies for treating sciatic nerve pain include over-the-counter (OTC) medications (such as Ibuprofen, Acetaminophen), steroid injections (Dexamethasone, Methylprednisolone), and, in severe cases, surgery, such as microdiscectomy to remove damaged spinal discs. Conservative approaches are typically preferred before considering surgical options.17, 18

Recently, occupational therapy-based interventions have garnered massive attention as an alternative therapeutic approach for sciatic nerve pain.19 These interventions can take the form of physical therapy exercises, massage, and postural alignments such as yoga poses. Major techniques include sciatic nerve mobilization, joint mobilization and manipulation, dry needling (the targeting of trigger points in muscles with a small needle, releasing hyper-irritable muscle tissue to reduce pain), gait training (the analysis and retraining of the patient's walking technique toward correct gait patterns), and active assisted range of motion (therapist-assisted movement of lower body parts, like the hip and legs, to facilitate movement in specific joints or muscles). These techniques are reported to be effective for strengthening and mobilizing tissue, relieving pain, reducing muscle spasms, improving mobility, and promoting a healing environment in the lower back to treat sciatic nerve pain.17 This review article discusses the role of occupation therapy in treating sciatica and examines different modalities of assessment and evaluation.

2 ANATOMY OF SCIATIC NERVES IN THE CONTEXT OF SCIATICA

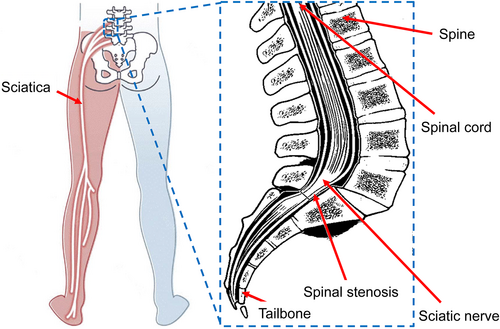

The sciatic nerve is a peripheral nerve that originates from the lumbosacral plexus, specifically from the spinal nerve roots L4 to S3. It is the largest and longest nerve in the human body, with a diameter of approximately 2 cm at its widest point (Figure 1). The sciatic nerve plays a crucial role in lower limb function, providing both motor and sensory innervation. The anatomical course of the sciatic nerve is significant.20 After its formation, it exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, passing beneath the piriformis muscle, after which it descends through the gluteal region and posterior thigh; it eventually bifurcates into the tibial and common fibular nerves at the apex of the popliteal fossa. While this bifurcation typically occurs above the back of the knee, in some people, it separates earlier, sometimes as it leaves the pelvis. Functionally, the sciatic nerve is responsible for the motor innervation of the posterior thigh muscles, including the hamstrings (biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus) and the hamstring portion of the adductor magnus. Through its terminal branches, it innervates all muscles of the leg and foot. The terminal branches also provide sensory function, supplying sensation to the skin of the lateral leg, heel, and both dorsal and plantar surfaces of the foot.21, 22

Anatomical course of the sciatic nerve. A schematic illustration showing the anatomy of the sciatic nerve and the area affected in sciatica.

Sciatic nerve issues in sciatica affect a person's ability to perform daily activities, impacting their quality of life.23, 24 Understanding the anatomy and function of the sciatic nerve is crucial for healthcare professionals, particularly when administering intramuscular injections in the gluteal region. To avoid damaging the nerve, injections should be given in the upper lateral quadrant of the gluteal region.

3 PATHO-MECHANICAL CHANGES DUE TO SCIATIC NERVE PAIN

Patho-mechanical changes resulting from sciatic nerve pain include a complex combination of structural, functional, and inflammatory alterations. Research indicates that mechanical compression and inflammatory responses significantly contribute to nerve root dysfunction, leading to the pain and neurological deficits associated with sciatica.25 For instance, intramuscular injections of analgesics such as diclofenac have been shown to induce severe histopathological changes in the sciatic nerve, including myelin and axon degeneration, which can exacerbate pain.26 Additionally, cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor, released from intervertebral disks can mediate nerve root changes, suggesting a biochemical basis for sciatica.27 Behavioral studies in animal models reveal that sciatic nerve injury leads to mechanical and cold allodynia, producing persistent pain states indicative of altered sensory processing.28 These findings highlight the multifaceted nature of patho-mechanical changes in sciatic nerve pain, underscoring the need for comprehensive therapeutic approaches.

4 ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION OF SCIATIC NERVE PAIN

Proper assessment and evaluation are crucial in determining the underlying causes of sciatic nerve pain and developing an effective treatment plan. The process typically involves a combination of diagnostic tests, examinations, and a thorough medical history review.

4.1 Diagnostic tests and examinations

4.1.1 Physical examination

A healthcare professional performs a comprehensive physical examination to assess muscle strength, reflexes, and range of motion. Specific tests, such as the straight leg raise test or the slump test, may be conducted to evaluate the extent of nerve irritation and identify the level of the spine affected.29-31

4.1.2 Imaging studies

Diagnostic imaging techniques play a crucial role in identifying factors contributing to sciatic nerve pain. X-rays can reveal structural issues such as bone spurs or misalignments that may compress the nerve.32-34 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers detailed soft tissue images, aiding in detecting herniated discs or spinal stenosis.35-37 Computed tomography scans can visualize bony structures for abnormalities.38-40 Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies are used to assess muscle and nerve electrical activity, respectively, aiding in evaluating the extent of nerve damage.41-43 These diagnostic tools provide valuable insights for healthcare professionals to aid the accurate diagnosis of underlying causes and the tailoring of effective treatment plans for individuals experiencing sciatic nerve pain.

4.2 Identifying underlying causes and contributing factors

During the assessment process, healthcare professionals aim to identify the underlying cause of sciatic nerve pain, as well as any contributing factors that may exacerbate or prolong the condition. Common underlying causes include herniated or bulging discs, which can put pressure on the sciatic nerve roots, spinal stenosis, which can lead to the narrowing of the spinal canal and compression of the nerve roots, and degenerative disc disease, in which deteriorating discs can cause nerve irritation or compression.44-54 Piriformis syndrome, where tightness or spasm in the piriformis muscle irritates the sciatic nerve, is another potential underlying factor.55-58 Trauma or injury, such as those resulting from accidents or falls, can also lead to sciatic nerve compression or damage. Additionally, healthcare professionals evaluate potential contributing factors such as age, occupation, lifestyle, body weight, and any pre-existing medical conditions that could exacerbate sciatic nerve pain. By thoroughly assessing the underlying causes and contributing factors, healthcare providers can develop a comprehensive treatment plan to effectively manage and alleviate the patient's pain, address the root issues, and provide targeted interventions to restore function and improve overall well-being.59

5 PHARMACOTHERAPY OF SCIATIC NERVE PAIN

Therapeutic drugs for sciatic nerve pain target various aspects of the condition, including inflammation, nerve transmission, and pain perception. The choice of medication depends on the underlying cause, severity of symptoms, and individual patient factors.60, 61 The major classes of drugs used to treat sciatic nerve pain and their mechanisms of action are as follows.

5.1 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often the first-line treatment for sciatic pain due to their anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. Mechanistically, NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are responsible for producing the prostaglandins that mediate inflammation and pain. Common NSAIDs include ibuprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac. These medications can help reduce inflammation around the sciatic nerve, thereby alleviating pain and improving mobility.62, 63

5.2 Opioid analgesics

In cases of severe sciatic pain that does not respond to NSAIDs, opioids may be prescribed for short-term use. Opioids bind to opioid receptors in the central nervous system, modulating pain perception. However, due to their potential for addiction and numerous side effects, their use is generally limited and closely monitored.18, 64

5.3 Muscle relaxants

Muscle relaxants can be beneficial in cases where muscle spasms contribute to sciatic pain. These drugs depress the central nervous system or directly affect skeletal muscle function, reducing muscle tension and spasms that may compress the sciatic nerve.65 Common muscle relaxants include cyclobenzaprine and baclofen.

5.4 Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsant medications, originally developed to treat epilepsy, have shown efficacy in managing neuropathic pain associated with sciatica.18 Drugs like gabapentin and pregabalin (Lyrica) modulate calcium channels in nerve cells, reducing the hyperexcitability of damaged nerves. These medications can be particularly effective in treating the characteristic burning or shooting pain of sciatica.66

5.5 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

TCAs, such as amitriptyline, are sometimes used to treat chronic sciatic pain. TCAs increase levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the nervous system, which can help modulate pain signals. TCAs can be especially useful in managing the sleep disturbances often associated with chronic pain conditions.67

5.6 Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs, which can be administered orally or via epidural injection for sciatic pain. By suppressing the immune response, they can reduce inflammation around affected nerve roots. While effective in providing short-term relief, their long-term use is limited due to potential side effects.68

5.7 Novel therapies

Researchers are exploring new therapeutic approaches for sciatic nerve pain. For instance, a study is investigating the use of clonidine, an alpha-2 agonist, administered as a tiny pellet into the lumbar epidural space. Clonidine works by blocking pain signals from reaching the brain and interrupting the inflammation that contributes to chronic pain.69, 70

5.8 Phytochemicals and natural compounds

Recent studies have identified several plant-derived compounds with potential therapeutic effects on sciatic nerve pain.71 These include β-caryophyllene, quercetin, resveratrol, rutin, vinorine, bromelain, and eugenol. These compounds exhibit various mechanisms of action, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective effects. For example, β-caryophyllene has shown promise in reducing oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, both of which are implicated in neuropathic pain.72 Quercetin has demonstrated the ability to promote functional motor and sensory recovery following sciatic nerve injury.73 Resveratrol and rutin have exhibited neuroprotective effects in animal models of sciatic nerve injury.74

5.9 Combination therapies

In many cases, combinations of different drug classes may be used to address various aspects of sciatic pain. For instance, an NSAID might be combined with an anticonvulsant to target both inflammation and neuropathic pain components. The specific combination depends on the individual patient's symptoms and response to treatment.75

5.10 Mechanism-based approach

Growing understanding of the underlying mechanisms of sciatic nerve pain has led to more targeted therapeutic approaches. For example, drugs that modulate neuroinflammation, such as SAFit2, have shown promise in reducing neuropathic pain. Similarly, compounds that target specific inflammatory pathways or ion channels involved in pain signaling are being investigated.76

5.11 Personalized medicine

Sciatic pain treatment is moving toward personalized medicine approaches. This involves tailoring therapies based on individual patient characteristics, genetic factors, and specific pain mechanisms. For instance, genetic variations in pain perception and drug metabolism can influence the effectiveness of certain medications for sciatic pain.77

5.12 Targeted drug delivery

Advances in drug delivery systems may offer new options for treating sciatic pain, with various groups developing novel drug delivery systems. These include the use of nanoparticles and biological nanovesicles such as exosomes, a type of extracellular vesicle, for the diagnosis and treatment of different diseases.78-80 A preclinical study explored the use of nanoparticle-mediated delivery of anti-inflammatory agents directly to the site of nerve compression. This approach provided sustained pain relief in an animal model of sciatica, suggesting potential for translation to human patients.81

6 SURGICAL INTERVENTION FOR SCIATIC NERVE PAIN—WHAT IS THE WAY FORWARD?

Surgical intervention for sciatic nerve pain remains a critical area of research and clinical practice as sciatica continues to be a significant cause of disability and reduced quality of life for many patients.82, 83 While conservative treatments are often the first line of defense, surgical options play an important role when non-operative measures fail to provide adequate relief. This review will explore the current state of surgical interventions for sciatic nerve pain and discuss potential future directions. Current Surgical Approaches Microdiscectomy remains among the most common surgical procedures for treating sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Gadjradj et al. (2022) found that microdiscectomy resulted in faster recovery of leg pain compared with conservative treatment, with sustained benefits at 1- and 2-year follow-ups. The procedure involves removing the herniated portion of the disc that compresses the nerve root, typically through a small incision. Minimally invasive techniques have gained popularity in recent years.84 A study comparing percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD) to open microdiscectomy for lumbar disc herniation found that PELD resulted in shorter hospital stays, less postoperative pain, and faster return to work, with similar long-term outcomes in terms of leg pain and functional improvement. For patients with lumbar spinal stenosis causing sciatic symptoms, decompressive procedures such as laminectomy or laminotomy may be considered.85 Another study evaluated the long-term outcomes of minimally invasive decompression surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. The researchers reported significant improvements in leg pain and walking distance that were maintained at a 5-year follow-up. In cases where spinal instability is a concern, fusion procedures may be recommended. However, the efficacy of fusion for degenerative conditions remains controversial.86 A systematic review by Yavin et al. (2017) found that while fusion procedures for degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis resulted in greater improvement in back pain compared to decompression alone, the clinical significance of this difference was questionable.87 Emerging techniques and future directions are as follows.

6.1 Regenerative therapies

There is growing interest in the use of regenerative therapies to treat disc degeneration, potentially avoiding the need for more invasive surgeries. A study investigating the use of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of degenerative disc disease reported significant improvements in pain and disability scores at 12 months with evidence of increased disc height on MRI. While these results are promising, larger randomized controlled trials are needed to establish the efficacy and safety of such approaches.88

6.2 Neuromodulation

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) has shown promise for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain, including some cases of sciatica.89 A study compared SCS with conventional medical management for patients with Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS) and persistent radicular pain. The study found that SCS resulted in significantly greater pain reduction and improved quality of life at 24-month follow-up.90

6.3 Robotic-assisted surgery

The integration of robotic technology in spinal surgery may improve the precision and consistency of procedures.91 A study compared outcomes of robotics assisted versus freehand pedicle screw placement in minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. The robotic-assisted group showed significantly lower rates of screw malposition and shorter operative times.92

6.4 Artificial intelligence in surgical planning

Machine learning algorithms are being developed to assist in preoperative planning and outcome prediction.93 One study utilized a deep learning model to predict the likelihood of successful outcomes following lumbar discectomy based on preoperative imaging and clinical data. The model showed high accuracy in identifying patients most likely to benefit from surgery, potentially improving patient selection and reducing the number of unnecessary procedures.94

Despite significant advances in surgical techniques for treating sciatic nerve pain, several critical challenges persist, demanding continued research and innovation in the field. Patient selection remains of paramount concern, with some studies highlighting the importance of preoperative factors in predicting surgical outcomes. The development of more sophisticated predictive models could greatly enhance patient selection processes and manage expectations more effectively.95-97 The issue of FBSS continues to plague a substantial proportion of patients98; incidence rates between 10% and 40% have been reported following lumbar spine surgery. This underscores the urgent need for research into the underlying mechanisms of FBSS and the development of targeted interventions.99 The long-term efficacy of surgical interventions remains a significant concern, as evidenced by reports revealing a diminishing benefit of surgery over time compared to non-operative treatments.100 This finding emphasizes the critical need for extended follow-up periods in future studies to better understand the long-term impacts of surgical interventions. Cost-effectiveness is another crucial consideration, particularly in the face of increasing financial pressures on healthcare systems. While reasonable short-term cost-effectiveness of lumbar disc herniation surgery has been reported, the long-term economic impact remains unclear; further research into the financial implications of newer surgical techniques and technologies is necessary.101, 102 Addressing these challenges will require a multifaceted approach, combining refinements in surgical techniques with advancements in regenerative medicine, targeted drug delivery, and neuromodulation.

7 ROLE OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

Occupational therapy is a client-centered healthcare profession that focuses on enabling individuals to participate in meaningful daily activities or “occupations” throughout their lives. The primary goal of occupational therapy is to promote health, well-being, and quality of life by helping people engage in the activities that are important to them despite physical, cognitive, or emotional challenges. Occupational therapists work with a diverse range of clients, including children with developmental disabilities, adults recovering from injuries or illnesses, and older adults experiencing age-related conditions. They employ a holistic approach, considering the physical, psychological, and social aspects of a person's life when developing intervention plans.

One of the core principles of occupational therapy is the belief that engagement in meaningful activities can have therapeutic benefits. Occupational therapists use various frames of reference to guide their practice. Examples include the biomechanical frame of reference, which focuses on motion during activity, and the client-centered frame of reference, which places the client's needs and goals at the center of the intervention.103 The sensory integration framework is commonly used in pediatric practice, particularly for children with developmental delays or autism spectrum disorders.104, 105 In addition to working directly with clients, occupational therapists often collaborate with other healthcare professionals, educators, and family members to create comprehensive care plans. They may recommend adaptive equipment, teach new skills, or suggest modifications to the environment to support their clients' independence and participation in daily activities.106, 107 The field of occupational therapy continues to evolve with emerging areas of practice including primary care interventions, pain management, and wellness programs. As healthcare systems shift toward more holistic and patient-centered approaches, the role of occupational therapy is likely to expand further. Occupational therapy provides a unique perspective on the relationship between activity and health, making it a valuable component of healthcare and rehabilitation services.103, 108, 109

Occupational therapy can play a crucial role in the management of sciatica by addressing functional limitations and promoting independence in daily life. The primary goal of occupational therapy interventions for sciatica is to alleviate pain and improve overall function. Table 1 lists and describes the different goals of occupational therapy. The holistic approach taken by occupational therapists considers not only the physical aspects but also the psychological, social, and environmental factors that contribute to an individual's well-being.

| Goal | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Pain management |

|

[110-113] |

| Functional mobility and independence |

|

[114-116] |

| Ergonomic adaptations |

|

[117-120] |

| Activity modification and pacing |

|

[121, 122] |

| Education and self-management |

|

[123] |

| Psychosocial support |

|

[124-126] |

8 OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS FOR SCIATICA

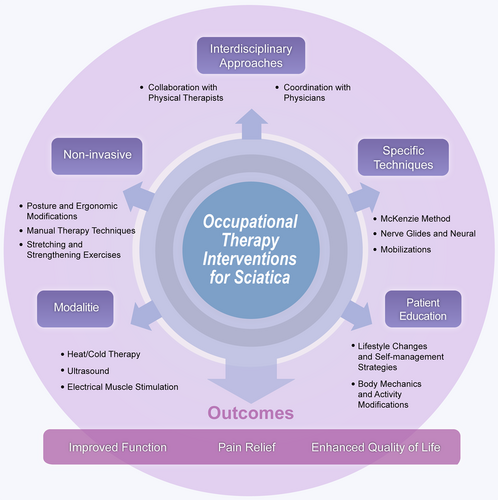

Occupational therapy interventions for sciatica encompass a range of non-invasive treatments aimed at reducing pain and improving function (Table 2). These include manual therapy techniques such as soft tissue mobilization and nerve glides, as well as therapeutic exercises to strengthen the core and lower-body muscles. Modalities such as heat therapy, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation may be employed to manage pain and promote healing. Patient education focuses on proper body mechanics, ergonomics, and self-management strategies.127-131 Specific techniques, such as the McKenzie Method, or neural mobilization exercises may be utilized.56, 132-136 Interdisciplinary approaches involve collaboration with physical therapists, pain specialists, and physicians to provide comprehensive care. Occupational therapists also encourage beneficial lifestyle modifications and assess adaptive equipment needs to enhance the patient's ability to perform daily activities and return to work. Figure 2 shows a flow chart depicting different types of intervention strategies employed in occupational therapy for sciatica.

| Intervention | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive Treatments | ||

| Posture and ergonomic modifications | Correction of posture and body mechanics, modifying workstations, seating, and equipment to reduce strain on the spine and sciatic nerve | [127, 128] |

| Stretching and strengthening exercises | Targeted exercises to improve flexibility, strengthen core and back muscles, and reduce pressure on the sciatic nerve | |

| Manual therapy techniques | Techniques like mobilizations, soft tissue massage, and joint manipulations to improve mobility, reduce muscle tension, and promote healing | |

| Modalities | ||

| Heat/cold therapy | Application of hot or cold packs to the affected area to reduce inflammation, muscle spasms, and pain | [127-129] |

| Ultrasound | Use of sound waves to generate deep heat within tissues, improving blood flow and promoting healing | |

| Electrical muscle stimulation | Application of electrical impulses to stimulate and contract muscles, reducing spasms and improving circulation | |

| Patient education | ||

| Body mechanics and activity modifications | Education on proper body mechanics, posture, and techniques for modifying activities to reduce strain on the sciatic nerve | [130, 131] |

| Lifestyle changes and self-management strategies | Education on weight management, stress reduction, and self-care strategies to prevent flare-ups and promote overall well-being | |

| Specific techniques | ||

| McKenzie method | A mechanical diagnosis and therapy approach that uses specific exercises and postures to centralize and alleviate sciatic nerve pain | [132-134] |

| Nerve glides and neural mobilizations | Techniques that involve gentle movements and stretches to mobilize and reduce tension on the sciatic nerve | [56, 135, 136] |

| Interdisciplinary approaches | ||

| Collaboration with physical therapists | Working closely with physical therapists to coordinate treatment plans and ensure continuity of care | [155, 156] |

| Coordination with physicians | Collaboration with physicians for medication management, injection therapies (e.g., epidural steroid injections), or surgical interventions in severe cases | |

A flow chart showing different therapeutic intervention strategies for occupational therapy.

Non-invasive treatments for sciatica target the underlying pathophysiology through multiple mechanisms. Posture and ergonomic modifications reduce mechanical stress on the sciatic nerve by optimizing spinal alignment and minimizing compression.137 Stretching exercises increase the flexibility of tight muscles that may be impinging on the nerve, while strengthening exercises improve spinal stability and reduce nerve irritation.138 Manual therapy techniques such as soft tissue mobilization can decrease muscle tension and improve blood flow around the affected area, promoting healing.139 Modalities such as heat therapy increase local circulation and muscle relaxation, whereas cold therapy reduces inflammation around the nerve root. Ultrasound generates deep tissue heating that can improve tissue extensibility and promote healing.137 Electrical stimulation may modulate pain signals and reduce muscle spasms that contribute to nerve compression.138 Patient education on proper body mechanics and activity modifications can help prevent further irritation of the sciatic nerve during daily activities.140 The McKenzie Method uses specific movements to centralize pain and reduce nerve root compression. Nerve gliding exercises aim to improve neural mobility and reduce adhesions around the sciatic nerve.138 Interdisciplinary approaches ensure the comprehensive management of various contributing factors.

In the context of outcome measures and monitoring disease progress, occupational therapists utilize a range of measures to assess the effectiveness of interventions. Pain scales, such as the Visual Analog Scale and Numeric Pain Rating Scale, are commonly used to quantify pain levels over time141-144; functional assessments evaluate improvements in activities of daily living, mobility, and participation in meaningful activities.145-147 Range of motion and strength measurements are also taken to monitor changes in physical capabilities, while patient-reported outcome measures such as the Oswestry Disability Index148-150 or the Sciatica Bothersomeness Index assess the patient's perception of their condition.151-154

Regular reassessments are conducted to track progress and adjust the treatment plan as needed. Objective measures, such as range of motion, strength, and functional tests, are combined with subjective reports from the patient on their pain levels, limitations, and overall well-being. Monitoring progress is crucial to ensure that occupational therapy interventions effectively address the underlying causes of sciatic nerve pain, improve the patient's ability to perform daily activities, alleviate symptoms, and enhance their quality of life. Ongoing communication between the occupational therapist, patient, and other healthcare professionals is essential for comprehensive progress tracking and achieving optimal outcomes.

9 HEALTHCARE DEVICES AND POSTURAL ALIGNMENTS FOR THE REHABILITATION OF SCIATIC PAIN

Healthcare devices play a crucial role in sciatic pain rehabilitation by providing targeted relief and promoting better posture. These devices, along with postural alignments achieved through sciatic nerve and joint mobilization, aim to alleviate pressure on the sciatic nerve, reduce pain, and improve mobility (Tables 3 and 4). Combining these interventions enhances comfort, aids in the management of symptoms, and supports overall well-being in individuals with sciatica.

| Device | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units |

|

[157-160] |

| Lumbar support devices |

|

[161-163] |

| Heat/Cold therapy products |

|

[164] |

| Ultrasound therapy devices |

|

[165-167] |

| Ergonomic seating and mobility aids |

|

[168-170] |

| Electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) devices |

|

[171-174] |

| Postural alignment | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral spine | Keep the back in a neutral position with the head positioned on top of the spine and ears above the shoulders. This helps maintain proper spinal alignment and reduces stress on the sciatic nerve | [175] |

| Avoid excessive curvature | Avoid excessively curving the lower back (lordotic posture) or hunching the upper back (kyphotic posture) while walking; these positions can overload spinal joints and muscles, potentially irritating the sciatic nerve | [176] |

| Avoid flat back | Avoid reducing the natural curve of the upper and lower spine while walking, as this increases stress on the lower back vertebrae and can fatigue back muscles, leading to sciatic nerve irritation | [177] |

| Avoid swayback posture | Avoid shifting the upper back backward and pelvis forward (swayback posture) while walking, as this increases the spinal curvature and can cause lower back muscle tension and fatigue, potentially compressing the sciatic nerve | [178] |

| Proper foot strike | Land between the midfoot and heel when taking a step, then gently roll onto the toes and push off into the next stride. This helps maintain a natural stride length and reduces impact on the spine and sciatic nerve | [17] |

10 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This work comprehensively covers the key aspects of occupational therapy intervention for sciatica-related nerve pain, highlighting the multifaceted approach taken by occupational therapists to address this debilitating condition. From assessment and evaluation to various treatment modalities, specific techniques, interdisciplinary collaboration, and progress monitoring, we underscore the holistic nature of occupational therapy in managing sciatica. The assessment and evaluation phase—which includes diagnostic tests, examinations, and the identification of underlying causes and contributing factors—lays the foundation for the development of effective treatment plans tailored to the individual's needs. This crucial step ensures that the interventions target the root cause of the sciatic nerve pain, rather than merely addressing the symptoms. Furthermore, we have discussed the diverse range of treatment modalities available to occupational therapists, including non-invasive treatments, technology-based options, patient education, and specific techniques, and have described an overall interdisciplinary approach. Non-invasive treatments, such as posture and ergonomic modifications, stretching and strengthening exercises, alongside manual therapy techniques, aim to alleviate pain, improve mobility, and promote healing without the need for invasive procedures. Modalities such as heat/cold therapy, ultrasound, and electrical muscle stimulation are also highlighted, providing occupational therapists with additional tools to manage pain, reduce inflammation, and improve circulation.

Several key challenges remain for optimizing surgical interventions for sciatic nerve pain, despite advances in techniques. Patient selection remains crucial, with preoperative factors significantly influencing outcomes. The persistent issue of FBSS, affecting 10%–40% of patients, highlights the need for better understanding and targeted interventions. Long-term efficacy is a concern, as the benefits of surgery may diminish over time when compared to non-surgical options. Cost-effectiveness, particularly in the long term, requires further evaluation. Addressing these challenges necessitates a multifaceted approach, including the combination of refined surgical techniques with advances in regenerative medicine, targeted drug delivery, and neuromodulation. Future research should focus on large-scale, long-term trials, improved predictive models, combination therapies, minimally invasive techniques, and personalized medicine approaches; advances in these areas would enhance patient outcomes and quality of life. In addition, patient education plays a pivotal role in empowering individuals with knowledge and self-management strategies, enabling them to take an active role in their recovery and preventing future flare-ups.

The work also emphasizes the importance of specific techniques, such as the McKenzie method, nerve glides, and neural mobilizations, which target the underlying mechanisms of sciatic nerve pain. These techniques, combined with an interdisciplinary approach involving collaboration with physical therapists and physicians, can be effective parts of a comprehensive and coordinated treatment plan. Monitoring progress through outcome measures is another crucial aspect covered in the presented outline. By regularly assessing pain levels, functional abilities, range of motion, and patient-reported outcomes, occupational therapists can evaluate the effectiveness of interventions and make necessary adjustments to ensure optimal outcomes. While this outline provides a comprehensive overview of occupational therapy interventions for sciatica-related nerve pain, there is still room for future research and exploration. As our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of sciatica and the efficacy of various interventions continues to evolve, occupational therapists must remain at the forefront of evidence-based practice.

Future research should focus on developing and validating new assessment tools and outcome measures specific to sciatica, enabling more accurate evaluation and progress monitoring. Additionally, exploring the potential integration of emerging technologies, such as virtual reality and telerehabilitation, could enhance the delivery of occupational therapy services and improve the accessibility of these interventions. Furthermore, investigating the long-term effects of occupational therapy interventions on sciatica and the potential for preventing recurrence would be valuable. Longitudinal studies could shed light on the sustainability of functional gains achieved through occupational therapy and inform strategies for maintaining long-term pain management and quality of life. Interdisciplinary collaboration will continue to play a crucial role in the management of sciatica-related nerve pain. Future research could explore innovative models of care that seamlessly integrate occupational therapy with other healthcare disciplines, fostering a truly collaborative approach to patient-centered care. In conclusion, the review presented here provides a comprehensive framework for occupational therapy interventions in the management of sciatica nerve pain. By addressing assessment, treatment modalities, specific techniques, interdisciplinary collaboration, and progress monitoring, occupational therapists can play a vital role in alleviating pain, improving the functional abilities, and enhancing the overall quality of life of individuals affected by this condition. However, continued research, innovation, and collaboration are essential to further refine and advance occupational therapy practices in this area, ensuring that individuals with sciatica receive the most effective, evidence-based care.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Sudha Thakur: Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft. Anoop Kumar: Writing—review & editing. Anne Dijkstra: Writing—review & editing. Abhimanyu Thakur: Conceptualization, investigation, validation, resources, writing—review & editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the Ramalingaswamy Re-entry Fellowship (Ref# BT/HRD/35/02/2006) from the Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science & Technology, Government of India.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not needed in this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data was created or analyzed in this study.