Early-Life Adversity Predicts Markers of Aging-Related Neuroinflammation, Neurodegeneration, and Cognitive Impairment in Women

Abstract

Objective

Despite the overwhelming evidence for profound and longstanding effects of early-life stress (ELS) on inflammation, brain structure, and molecular aging, its impact on human brain aging and risk for neurodegenerative disease is poorly understood. We examined the impact of ELS severity in interaction with age on blood-based markers of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, brain volumes, and cognitive function in middle-aged women.

Methods

We recruited 179 women (aged 30–60 years) with and without ELS exposure before the onset of puberty. Using Simoa technology, we assessed blood-based markers of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, including serum concentrations of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neurofilament light chain (NfL). We further obtained T1-weighted and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images to assess brain volumes and we assessed cognitive performance sensitive to early impairments associated with the development of dementia, using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Automated Test Battery. We used generalized additive models to examine nonlinear interaction effects of ELS severity and age on these outcomes.

Results

Analyses revealed significant nonlinear interaction effects of ELS severity and age on NfL and GFAP serum concentrations, total and subcortical gray matter volume loss, increased third ventricular volume, and cognitive impairment.

Interpretation

These findings suggest that ELS profoundly exacerbates peripheral, neurostructural, and cognitive markers of brain aging. Our results are critical for the development of novel early prevention strategies that target the impact of developmental stress on the brain to mitigate aging-related neurological diseases. ANN NEUROL 2025;97:642–656

Aging, an inevitable process, is the primary risk factor for neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's disease (AD).1, 2 With the global elderly population growing, the burden of neurodegenerative diseases is expected to rise substantially,3 necessitating novel preventive approaches. Importantly, the pathological processes underlying neurodegenerative diseases begin years before clinical manifestation.4 Aging in the brain includes neuroinflammation as well as neurostructural and neurofunctional alterations,5 leading to cognitive decline.6 Early-life stress (ELS), for example, abuse, neglect, or deprivation during childhood, is highly prevalent in the population and can trigger health-related risk cascades across life.7, 8 Compelling evidence suggests that ELS exposure is associated with accelerated biological aging, reflected in telomere shortening and epigenetic age.9, 10 ELS has profound and long-lasting effects on the immune system and brain11 that overlap with brain aging mechanisms. It is conceivable that ELS contributes to pathological brain aging and represents an important risk factor for neurodegenerative diseases.

Neuroinflammation, which increases with age and acute challenges, is a tightly controlled mechanism that sensitizes the brain to stress.12 Whereas initially protective, persistent neuroinflammation can prime glial cells,13, 14 amplifying neuroinflammatory responses, and driving neurodegenerative disorder progression.15, 16 Normal brain aging is associated with progressive gray matter atrophy and white matter microstructure changes beginning in early adulthood.17 Pronounced or accelerated brain volume loss is a feature of neurodegenerative disorders.18 Of note, there are distinctive regional and temporal patterns of pathological changes in different neurodegenerative disorders.19 In AD, early pathological changes and volume loss often affect the neocortex and hippocampus, with later stages involving widespread cortical atrophy.20 Recent imaging techniques offer precise quantification of brain structure changes in AD, superseding previous markers, such as ventricular enlargement.21, 22 However, ventricular enlargement, resulting from gray and white matter changes in the surrounding regions,23 remains a valid marker for neurodegeneration and has been identified as an early prognostic predictor for subsequent cognitive decline in patients with AD over time.24

Numerous studies report sustained low-grade peripheral inflammation in adults exposed to ELS.25 Animal models, that is, maternal separation or low maternal care, suggest that ELS contributes to the initiation and perpetuation of chronic neuroinflammation26-28 and causally impairs adult cognition by affecting neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity.29 Human studies link ELS to global gray and white matter reductions,30 lower adult cognitive ability, and greater likelihood of AD diagnoses31, 32 and other neurodegenerative diseases.33 Few studies report ELS-associated cognitive effects persisting into middle age,34 whereas evidence on its impact on later-life cognitive performance is conflicting.35

Despite this convergence, a significant gap exists regarding how ELS specifically contributes to pathological brain aging and intersects with aging mechanisms relevant to dementia development. One recent study provided evidence for effects of life stress on AD-related neuropathology, suggesting that childhood stress specifically impacts AD risk.36 Our study extends and deepens this evidence by focusing on the early life period. We hypothesized that ELS before pubertal onset is associated with aging-related neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and cognitive impairment.

Our study uses a high-risk approach by specifically focusing on women. The scientific rationale for this focus is based on the convergence of several lines of evidence: (1) women are at a substantially greater risk to develop AD as compared with men37; (2) women exhibit heightened stress vulnerability as compared with men38; (3) estrogen modulates neural stress responses, neuroplasticity, and microglia activation39, 40; and (4) women are at a greater risk for pathological outcomes of ELS such as depression.41 Hence, women may represent a high-risk group with vulnerability to ELS-related pathological brain aging. We therefore focused our study on women with the aim to provide evidence for our hypothesis of an impact of ELS on brain aging within this high-risk population. A focused understanding of ELS-related disease mechanisms contributing to AD risk in women is a critical first step in establishing the need for expanded studies designed to detect potential sex-specificity of the identified mechanisms and putative disproportionate risk in women relative to men.

To that end, we recruited a sample of middle-aged women with and without various forms of ELS. We assessed ELS histories, peripheral biomarkers of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, global brain volumes, and cognitive function in domains sensitive to the development of cognitive impairment. We used generalized additive models (GAMs)42 to test nonlinear interaction effects between ELS severity and age. Understanding early life determinants and mechanisms of later-life neurodegenerative diseases is critical to identify precise targets for the early interception of disease mechanisms in those at risk.

Methods

Study Design

The NeuroCure (DFG EXC 257)-funded study used a retrospective, cross-sectional design with standardized visits at the Neuroscience Clinical Research Center and the Berlin Center for Advanced Neuroimaging at Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin. ELS severity scores and age in years were used as continuous predictors of biomarker, brain, and cognitive outcomes. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and was conducted in accordance with the Ethical Principles for Medical Research as established by the Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample

We recruited 184 healthy women aged 30 to 60 years to capture an age range during which alterations associated with brain aging occur. We recruited exclusively women from Berlin via advertisements online, in the public transportation system, and across the city. We did not target specific neighborhoods, events, or clinical populations. As explained above, we used a high-risk population approach and focused our study on women. In brief, the rationale for this focus is based on higher AD risk,37 greater vulnerability to stress,38 and a higher risk to develop certain adverse outcomes of ELS41 in women as compared with men. This targeted approach allows us to yield evidence of the impact of ELS on brain aging within this high-risk group. We acknowledge that this design does not allow us to detect sex-specific vulnerability. Yet, our approach follows established guidelines advocating for targeted research in high-risk populations and in women's health to establish foundational evidence for future expanded studies. Indeed, women may exhibit a specific vulnerability to the effects of ELS on AD risk; however, our study was not designed to test this hypothesis.

Women were excluded if they had a formal physician-derived diagnosis of neurological disorders, including manifested AD and other dementias, as ascertained by neurological examination and anamnesis and by monitoring anti-dementia medication intake. Of note, we did not exclude mild cognitive impairment (MCI), given that early cognitive impairment is one of the primary outcomes of the study. Further exclusion criteria included recent use of immunosuppressants, any medicines with central nervous system (CNS) effects, current pregnancy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contraindications. Current psychiatric disorders were exclusionary, with the exception of depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to their high prevalence in individuals with ELS and the potential for a mediating relationship between ELS and outcomes. Excluding affective disorders related to ELS would have resulted in a highly selective sample characterized by specific resilience to ELS, which may also affect resilience to dementia development. Our final sample consisted of 179 women who participated in the study between March 2021 and September 2022. All participants reported their sex and gender as female. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

| N = 179 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender/sex, n (%) | Women/femalea | 179 (100) |

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 41.0 ± 9.2 | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | European/White | 168 (93.9) |

| Middle Eastern | 2 (1) | |

| African | 2 (1) | |

| Asian | 2 (1) | |

| Latina | 2 (1) | |

| Missing | 3 (1.7) | |

| Education, n (%) | Left formal education before age 16 yrs | 4 (2.2) |

| Left formal education at age 16 yrs | 28 (15.6) | |

| Left formal education at age 17 to 18 yrs | 35 (19.6) | |

| Undergraduate degree or equivalent | 39 (21.8) | |

| Master's degree or equivalent | 47 (26.3) | |

| PhD or equivalent | 22 (12.3) | |

| Missing | 4 (2.2) | |

| Monthly income, n (%) | Under 150€ | 0 (0) |

| 150€ to 2,500€ | 69 (38.5) | |

| 2,500€ to 4,000€ | 38 (21.2) | |

| 4,000€ to 10,000€ | 43 (24.0) | |

| > 10,000€ | 2 (1.1) | |

| Missing | 27 (15.1) | |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 23.9 ± 4.7 | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Single | 90 (50.2) |

| Married/in partnership | 69 (38.5) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 20 (11.2) | |

| Children, n (%) | Yes | 70 (39.1) |

| No | 100 (55.9) | |

| Missing | 9 (5.3) | |

| ACE score, n (%) | 0 | 74 (41.5) |

| 1 to 3 | 58 (32.6) | |

| 4+ | 47 (26.4) | |

| BDI-II score, mean ± SD | 8.8 ± 9.7 | |

| STAI state score, mean ± SD | 37.7 ± 11.3 | |

| STAI trait score, mean ± SD | 39.9 ± 13.1 | |

| PTSD symptom number, mean ± SD | 2.9 ± 4.5 |

- ACE = adverse childhood experience; BDI-II = Beck's Depression Inventory II; BMI = body mass index; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; SD = standard deviation; STAI = State Trait Anxiety Inventory.

- a Self-reported gender identity and biological sex were consistent across all participants.

Assessment of Early-Life Stress

We included women with and without ELS exposure. Presence or absence and severity of ELS were assessed using the German version of the Comprehensive Trauma Interview (CTI),43 a psychometrically validated tool demonstrating good inter-rater reliability with kappa values ranging from 0.51 to 0.7644 and good predictive validity for psychiatric outcomes.43 In our study, the CTI demonstrated a high level of internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.84. For validation purposes, we used the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)45 and the correlation between CTI scores and CTQ scores in our sample was 0.77 (p < 0.001), demonstrating good convergent validity.

Exposure levels, that is, severity scores, were determined by counting items corresponding to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACE)46 in the CTI and included emotional, sexual, and physical abuse, emotional and physical neglect, witnessing domestic violence, household substance abuse, family psychiatric disorders or suicide attempt, or death by suicide, imprisonment of family member, instability due to parental separation/divorce, and death of a primary caregiver. The ACE score, ranging from 0 to 11, was calculated for each participant as the sum of the number of experienced stressors before menarche (see Table 1). For detailed score distributions, see Supplementary Figures S1 to S3.

We used menarche as a developmental cutoff to define the early life period, as opposed to a certain cutoff age. Our approach to define early life by a developmental stage rather than by a specific age is rooted in the available literature regarding sensitive periods for stress effects.47, 48 Notably, hormonal changes occurring with the onset of puberty impact both stress reactivity and neuroplastic responses.49, 50 Stress before and after menarche has differential long-term effects on brain structure and function.51 Puberty marks a transition where the focus of the child shifts from needs expected from caretakers to needs related to peers.52 Importantly, using menarche as a developmental cutoff to define the early life period accounts for individual variability in pubertal timing with impact on brain outcomes. Of note, it has been reported that ELS may impact pubertal development. To exclude potential effects of ELS exposure on age at menarche, we assessed associations between age at menarche, ELS scores, and all outcome variables. The mean age of menarche in our sample was 12.98 years (standard deviation [SD] = 1.27). No significant correlations were found between age at menarche and ELS scores or any outcome variables (see Supplementary Materials for details).

Blood Sampling and Assays

We assessed concentrations of blood-based biomarkers of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration using both serum and plasma. Serum measures were used for glial fibrillary acidic protein (sGFAP), neurofilament light chain (sNfL) and tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (sp-tau181). Amyloid-β 42 (pAβ42) concentrations were assessed in plasma.

These blood-based biomarkers reliably reflect protein levels in the CNS: GFAP is an astrocytic protein expressed in the CNS. Elevated peripheral levels of GFAP in plasma or serum are indicative of astroglial activation or injury within the CNS. Thus, peripherally measured GFAP serves as a marker of neuroinflammation.53 NfL is a structural protein expressed predominantly in neurons. Its presence in peripheral blood correlates with axonal damage or degeneration, confirming that it is a reliable biomarker for neurodegenerative processes and CNS injury.54 P-tau181 is a marker associated with neurodegenerative diseases, particularly AD and other tauopathies. Changes in p-tau181 levels in blood reflect pathological processes occurring in the CNS, including neuroinflammation and tau-related neurodegeneration.55 Aβ42 is a peptide involved in the formation of amyloid plaques, a hallmark of AD. Blood levels of Aβ42 are validated to reflect amyloid pathology within the CNS.56 The use of serum for GFAP, NfL, and p-tau181 as opposed to plasma is supported by studies demonstrating strong correlations between serum and plasma levels of these biomarkers.57, 58 Specifically p-tau181 in serum has been extensively validated as comparable to plasma p-tau181 across different assay types, including the Quanterix Single-Molecule Analysis Technology (SIMOA; Simoa) assay used in this study, with robust separation between diagnostic groups and strong correlations with CSF measures.59, 60

Venous blood was collected in EDTA and serum tubes (BD Vacutainer) and centrifuged. Serum samples were allowed to clot for 30 minutes at room temperature before centrifugation. Plasma and serum samples were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. The sGFAP (n = 10 missing), sNfL (n = 8 missing), and sp-tau181 (n = 9 missing) levels were measured using SIMOA at Labor Berlin—Charité Vivantes GmbH, using commercially available kits (Quanterix, Billerica, MA, USA). For the SIMOA assay, calibrators and high versus low controls were run in duplicates as quality controls, whereas samples were run in singlicates. The intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) were 2.05% for sGFAP and 7.45% for sp-tau181, whereas singlicate measures are formally accredited by Labor Berlin for sNfL. Missing data pertain to blood sampling failure. The pAβ42 was measured using a commercial Human Aβ42 Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Henningsdorf, Germany). The intra-assay CV was 20.2% and the inter-assay CV was 14.9%.

MRI Acquisition and Data Preprocessing

Structural MRI was performed using a 3 T PRISMAFit MRI scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a standard 64-channel head coil. Three-dimensional T1-weighted (T1w) magnetization prepared rapid acquisition of gradient echo (MPRAGE) and T2-weighted (T2w) SPACE images were acquired for all participants using the following scan parameters: T1w TE = 2.22 ms, TR = 2,400 ms, flip angle = 8, bandwidth = 220 Hz/Px, FOV = 256 mm, resolution 0.8 mm isotrope, and TA = 6:38 minutes (T2w) TE = 563 ms, TR = 3,200 ms, bandwidth = 744 Hz/Px, FOV = 256 mm, resolution 0.8 mm isotrope, TA = 5:57 minutes. Images of 172 participants were organized according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard. For 7 women, imaging protocols were incomplete or cancelled mid-scan. The T1w images were corrected for intensity non-uniformity with N4BiasFieldCorrection,61 distributed with ANTs 2.3.362 (RRID: SCR_004757), and used as T1w-reference throughout the workflow. The T1w-reference was then skull-stripped with a Nipype implementation of the antsBrainExtraction.sh workflow, using OASIS30ANTs as the target template. Brain tissue segmentation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), white matter (WM), and gray matter (GM) was performed on the brain-extracted T1w using fast (FSL 6.0.5.1:57b01774 and RRID:SCR_002823). Brain surfaces were reconstructed using recon-all applied to the T1w and the T2w images (FreeSurfer 6.0.1 and RRID:SCR_00184763). The preprocessing pipeline was run using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)prep focusing on the structural part within the individual subject space.64 We extracted volume data of the following global structures: total brain volume (TBV; all segmented brain tissue without ventricles, CSF, and choroid plexus), total gray matter volume (tGMV), total white matter volume (tWMV), subcortical gray matter volume (sGMV), and lateral, third, and fourth ventricular volumes, which serve as indicators for dementia risk (see above) as well as intracranial volume (ICV).

Assessment of Cognitive Function

Cognitive function was assessed using tasks from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery65 (CANTAB). Tasks sensitive to the development of cognitive impairment that may be observed in early stages of AD, including MCI, were selected. Tasks included the Spatial Working Memory task (SWMS), which tests executive function and measure of strategy as well as working memory errors. This task is impacted by visuo-spatial information retention-deficits often observed in early stage AD. The Rapid Visual Information Processing (RVPA) task, which provides a measure of sustained attention, and the pattern recognition memory percent correct instant (PRMPCI) task, which tests visual pattern recognition memory in a 2-choice forced discrimination paradigm, has been shown to be particularly sensitive to temporal lobe dysfunction. Tasks were presented in fixed order to all participants as follows: (1) PRMPCI (n = 1 missing), (2) SWMS (n = 6 missing), and (3) RVPA (n = 5 missing). For details on tasks, see the Supplementary Material. Of note, we did not use the CANTAB for diagnostic purposes, and formal diagnoses of prodromal AD or MCI were not made based on task performance. The CANTAB does not provide standardized clinical cutoffs for diagnostic classification.

Psychiatric and Socioeconomic Assessment

Psychiatric diagnoses were assessed by standardized clinical interview.66 Current depressive symptoms were assessed using the German version of the Beck's Depression Inventory II (BDI-II).67 Current symptoms of PTSD were assessed using the German version of the short screening scale for DSM-IV.68 Anxiety was assessed using the German version of the Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).69 Socioeconomic status (SES) was defined as a combination of educational level (assessed in categories from less than high school to advanced degrees and recoded into values from 1 through 5) and household monthly income (assessed in categories from ≤ 100€ to ≥ 20,000€ and recoded into values from 1 through 5).70 These measures were used as covariates.

Statistical Analysis

Biomarker concentrations were natural-log-transformed for analysis, as concentrations were not normally distributed. Global GM and WM and ventricular volumes were adjusted by ICV. Bivariate Pearson correlations were computed to inspect linear associations between all dependent variables (DVs), age, and ACE score. Linear models, with an interaction term between age and ACE score, were implemented to assess heteroscedasticity and normality (linear model). These models are provided in the Supplementary Table S1. Next, separate GAMs were implemented for all DVs to investigate the nonlinear interaction effects between ACE score and age in the prediction of outcomes (model 1). Tensor product smooth terms were utilized to model this nonlinear interaction effect with default smoothing functions (thin plate regression splines which are the default in the mgcv package in R), and model fitting was performed using the Restricted Maximum Likelihood method. Goodness of fit for model 1 was tested in comparison to a GAM with a tensor product smooth term, capturing the interaction effect stratified by the levels of age for all DVs (model 2) as several DVs correlated linearly with age. Model fit was assessed using a combination of Akaike Information Criteria, Bayes Information Criteria, residual deviance, and residual degrees of freedom (see Supplementary Table S2). The model that best balanced the theoretical expectations and relevant fit criteria was retained as the main model, that is, model 1. Significant smooth terms for the nonlinear interaction effects between age and ACE score in predicting outcomes in each of the models indicate that the relationship between these predictor variables and DVs is not adequately captured by a simple linear relationship.

As pAβ42 concentrations were below the ELISA detection limit in 79 women, the participants were stratified into 2 groups by ELS exposure, that is, ELS− (≤ 2 ACE) versus ELS+ (≥ 3 ACE), and an exploratory analysis was conducted using a Chi-square test to assess for between-group differences in detectability.

We assessed the impact of symptom severity of depression, state and trait anxiety, PTSD, and SES by integrating these variables as linear covariates into the main model. Bivariate Pearson correlations were conducted among these covariates, age, and ACE scores (Supplementary Table S3). The model performance was compared with and without covariates (Supplementary Table S4). Variance inflation factor (VIF) analyses were conducted to evaluate multicollinearity.

All statistical analyses were run in R Project for Statistical Computing (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria; version 4.1.2, 2021) and IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM, version 29, 2022). GAMs were implemented using the “mgcv” package for R.71 All analyses account for multiple comparisons conducted within each domain and p value adjustments were applied using the Benjamini-Hochberg (false discovery rate [FDR]) method. All reported p values in the Results section represent the adjusted p values. The significance level was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Descriptives

Bivariate correlations of all predictors and DVs are depicted in Table 2. Age was positively associated with sNfL concentrations, sGFAP concentrations, lateral and third ventricular volumes, and CANTAB SWMS. Age was negatively associated with TBV, tGMV, sGMV, tWMV, and CANTAB RVPA and PRMPCI. Age was not associated with sp-tau181 levels or fourth ventricular volume. There were no linear correlations between ACE score and any of the DVs. For the subsequent nonlinear GAM analyses, model 1 was used for all DVs, as described above.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | |||||||||||||

| 2. ACE score | 0.079 | – | ||||||||||||

| 3. sGFAP | 0.203** | –0.049 | – | |||||||||||

| 4. sNfL | 0.391** | 0.101 | 0.415** | |||||||||||

| 5. sp-tau181 | 0.020 | 0.022 | 0.309** | 0.215** | - | |||||||||

| 6. TBV | 0.257** | 0.074 | 0.119 | 0.127 | 0.077 | |||||||||

| 7. tGMV | 0.315** | 0.105 | 0.110 | 0.115 | 0.084 | 0.880** | - | |||||||

| 8. sGMV | –0.216** | –0.037 | –0.037 | –0.132 | 0.001 | 0.772** | 0.824** | – | ||||||

| 9. tWMV | –0.175* | –0.079 | –0.029 | –0.117 | 0.004 | 0.830** | 0.609** | 0.609** | – | |||||

| 10. Lateral ventricle volume | 0.206** | 0.018 | 0.072 | 0.154* | –0.045 | –0.467** | –0.495** | –0.449** | –0.560** | – | ||||

| 11. Third ventricle volume | 0.360** | 0.082 | 0.083 | 0.120 | 0.014 | –0.375** | –0.408** | –0.338** | –0.404** | 0.713** | – | |||

| 12. Fourth ventricle volume | 0.147 | 0.009 | 0.020 | 0.048 | –0.087 | –0.011 | 0.078 | 0.067 | –0.131 | 0.082 | 0.156* | – | ||

| 13. SWMS | 0.285** | 0.088 | –0.074 | 0.026 | –0.056 | 0.041 | –0.017 | 0.003 | 0.028 | 0.006 | 0.050 | 0.037 | – | |

| 14. RVPA | –0.214** | –0.073 | 0.108 | 0.076 | 0.004 | 0.022 | 0.034 | 0.070 | 0.070 | –0.084 | –0.209** | –0.116 | –0.385** | – |

| 15. PRMPCI | –0.274** | –0.120 | 0.019 | –0.044 | 0.063 | –0.045 | 0.044 | –0.010 | –0.017 | –0.053 | –0.188* | –0.009 | –0.214** | 0.339** |

- ACE = adverse childhood experience; Pearson r; PRMPCI = pattern recognition memory percent correct instant; RVPA = rapid visual information processing; sGFAP = serum glial fibrillary acidic protein; sGMV = subcortical gray matter volume; sNfL = serum neurofilament light chain; sp-tau181 = serum phosphorylated tau 181; SWMS = spatial working memory strategy; TBV = total brain volume; tGMV = total gray matter volume; tWMV = total white matter volume.

- * p < 0.05

- ** p < 0.01

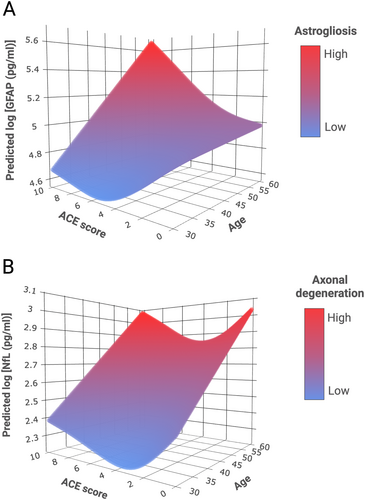

Associations of ELS Severity and Age With Blood-Based Biomarker Concentrations

Levels of all peripheral biomarker concentrations correlated significantly with one another (see Table 2). GAM analysis revealed a significant non-linear interaction effect between age and ACE score in predicting sGFAP and sNfL concentrations (Table 3). The model for sGFAP indicates a more pronounced age-dependent increase in sGFAP concentrations with higher ACE exposure levels (Fig 1A). The model for sNfL shows a U-shaped curve, with highest predicted sNfL concentrations at high (7+) ACE exposure levels and lowest predicted sNfL concentrations at low to moderate (1–3) ACE exposure levels (Fig 1B). There was no statistically significant interaction effect between age and ACE score in predicting sp-tau181 (see Table 3). The exploratory analysis on detectability of Aβ42 in plasma revealed that pAβ42 was more frequently detectable in the ELS+ (55%) than in the ELS− group (45%; χ2(2) = 5.57, p = .018).

| Response variable | edfa | F value | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| sGFAP | 4.35 | 3.22 | 0.012* |

| sNfL | 3.28 | 11.24 | < 0.001** |

| sp-tau181 | 3.089 | 0.046 | 0.987 |

| TBV | 3 | 5.097 | 0.006** |

| tGMV | 3.001 | 6.84 | 0.001** |

| sGMV | 3.001 | 3.126 | 0.049* |

| tWMV | 3.001 | 2.311 | 0.117 |

| Lateral ventricular volume | 6.164 | 1.69 | 0.129 |

| Third ventricular volume | 4.367 | 4.98 | 0.001** |

| Fourth ventricular volume | 3.002 | 1.36 | 0.257 |

| SWMS | 3.71 | 4.12 | 0.003** |

| RVPA | 3.08 | 3.2 | 0.024* |

| PRMPCI | 3.64 | 3.81 | 0.005** |

- GAM = generalized additive model; PRMPCI = pattern recognition memory percent correct instant; RVPA = rapid visual information processing; sGFAP = serum glial fibrillary acidic protein; sGMV = subcortical gray matter volume; sNfL = serum filament light chain; sp-tau181 = serum phosphorylated tau 181; SWMS = spatial working memory strategy; TBV = total brain volume; tGMV = total gray matter volume; tWMV = total white matter volume. Adjusted p values shown.

- a Smooth term estimated degrees of freedom (edf) provides an estimate of the model fluctuation.

- * p < 0.05

- ** p < 0.01

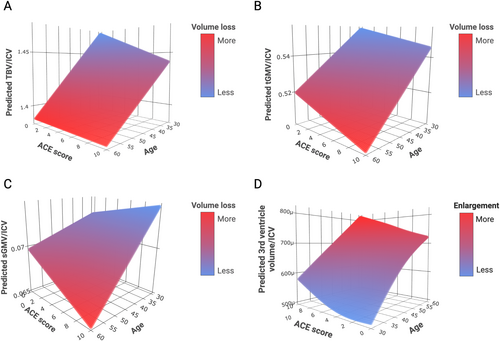

Associations of ELS Severity and Age With Global Brain and Ventricular Volumes

GAM analysis revealed that the smooth terms for the nonlinear interaction effect between age and ACE score in predicting TBV, tGMV, sGMV, and third ventricular volume were significant (see Table 3). The models for both TBV and tGMV show a more pronounced decrease in volume with increasing age and higher ACE exposure level (Fig 2A, B). Interestingly, the model for sGMV shows an increase in volume with increasing ACE exposure level at a younger age and a decrease, that is, faster deterioration, in volume with increasing ACE exposure level at an older age (Fig 2C). The model for the third ventricular volume predicts the largest ventricle size at the highest age and highest ACE exposure level (Fig 2D). There were no significant interaction effects between age and ACE score in predicting tWMV or lateral or fourth ventricular volumes.

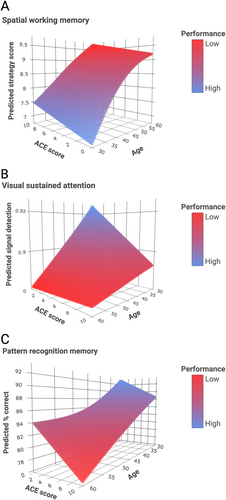

Associations of ELS Severity and Age With Cognitive Function

GAM analysis revealed a significant interaction effect between ACE score and age in predicting RVPA, SWMS, and PRMPCI (see Table 3). The model for SWMS predicted the highest scores at low ACE exposure level and young age and the lowest scores at higher ACE exposure level and older age (Fig 3A). The model for RVPA indicates a more pronounced cognitive dysfunction with higher ACE exposure level at a younger age (Fig 3B). The model for PRMPCI indicates a more pronounced age-dependent cognitive impairment with higher ACE exposure level (Fig 3C).

Adjustment for Psychiatric Symptoms and Socioeconomic Status

Bivariate correlation analysis revealed significant correlations among all 4 psychiatric symptom measures, SES, and ACE scores (see Supplementary Table S3). VIF analysis indicated multicollinearity of these variables with ACE scores. When including these covariates (psychiatric symptoms and SES) in the main model (as calculated in model 3), we found that the above effects remained statistically significant for 13 of 15 outcomes (see Supplementary Table S4). For 2 cognitive outcomes (RVPA and PRMPCI), effects were attenuated by SES, but remained at a statistical trend level. Psychiatric symptoms as covariates had no effect in model 3.

Discussion

We, here, present results on predictive interaction effects of ELS exposure level and age on 3 domains of brain aging indicators in a community sample of middle-aged women. Notably, we observed profound nonlinear interaction effects of ELS exposure level and continuous age on concentrations of biomarkers of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, as well as global brain volumes and cognitive outcomes sensitive to cognitive impairment. Our results suggest that ELS contributes to exacerbated brain aging in distinctive temporal patterns.

We show that, with increasing ELS exposure levels, sGFAP concentrations, reflecting neuroinflammation and glial cell dysfunction, are higher in women as they age. Our results may reflect early indicators of developing CNS disease at higher age and higher ELS exposure levels, given that recent clinical studies have reported elevated plasma GFAP levels at pre-symptomatic stages of CNS diseases.72 We further show that sNfL concentrations, reflecting axonal damage and neuronal death, increase with age, replicating previous work.73 Strikingly, this increase in sNfL levels with age is more pronounced in women with high (4+) ELS exposure levels or no ELS exposure, showing a bimodal or U-shaped distribution. Hence, women with low to moderate ELS exposure had lower predicted sNfL concentrations at each age, which may suggest a form of “stress inoculation” or resilience.74 Notably, experimental variation in stressor dose in animal models of ELS provides causal evidence that exposure to milder forms of stress in the postnatal period can result in an adult phenotype with lower stress reactivity compared with animals with no stress exposure. Neuroimmune responses can differ depending on stressor qualities, such as type, controllability, and duration, especially in an ELS-primed condition.75 The concept of post-traumatic growth posits that individuals may experience personal strengthening, improved adaptation, and increased resilience as a result of overcoming previous trauma.76 The precise mechanisms explaining the U-shaped relationship between ELS exposure levels and sNfL concentrations remains to be scrutinized in future studies. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not see any interaction effects of ELS and age on sp-tau181 in our sample, consistent with findings from the previous study on the impact of stress on AD pathologies.36 Studying healthy middle-aged women may have prevented us from detecting changes in sp-tau181, which typically occur at later stages in the progression of tauopathies, downstream to changes in Aβ42 levels.77 We did observe a higher proportion of detectable pAβ42 in women with medium to high ELS exposure, although this result is exploratory in nature. Given that we assessed biomarker concentrations in blood and not in CSF, it is important to consider whether peripheral concentrations accurately reflect CNS concentrations. Indeed, several studies have confirmed that blood and CSF levels of NfL, GFAP, and Aβ42 are highly correlated,78, 79 although the evidence is mixed, particularly regarding the correspondence between different blood-based assays and CSF or positron emission tomography-based Aβ42 measures.80 Hence, consideration of detection methods is crucial. In particular, newer high-precision methods, such as immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry, offer greater accuracy than traditional ELISA assays.81 Future research using advanced detection methods in both blood and brain tissue are essential for exploring these effects with greater accuracy. Taken together, our findings are in line with the recently published study36 that assessed the impact of life stress on CSF biomarkers and found a specific impact of stress exposure during childhood on these markers. Notably, as opposed to the published study,36 our sample included middle-aged women aged 30 to 60 years, but not individuals aged > 60 years. We chose to focus our study on identifying effects of ELS on outcomes in a middle-aged sample, because we were interested in detecting early signs of brain aging deviation or acceleration, as a function of ELS exposure, reflecting prodromal risk. At an older age, pathophysiological markers of neurodegenerative disorders may manifest more strongly, and effects of ELS may be even more pronounced.

At the brain structural level, our results demonstrate that the impact of ELS exposure level on TBV, tGMV, and sGMV varies depending on the individual's age at assessment. Increased ELS exposure levels are associated with smaller tGMV already at a younger age, potentially suggesting more immediate neurotoxic effects of stress hormones. Notably, women with high levels of ELS exposure show increased sGMV in younger adulthood and a markedly smaller sGMV in older adulthood. Previous studies have linked ELS to subcortical volume enlargements in children and young adults.82, 83 Our results may reflect an initial experience-dependent neuroplastic response in the limbic regions and a steep deterioration due to accelerated aging-related degeneration. This hypothesis must be tested in longitudinal studies. We further demonstrate that higher ELS exposure levels are associated with larger volumes of the third ventricle. Third ventricular enlargement has been shown to be a clinically meaningful marker of disease progression in MS, AD, and other neurological disorders.84, 85 The third ventricle lies adjacent to structures such as the hypothalamus, a region critical for regulating stress responses.86 Ventricular enlargement may not only indicate localized GM atrophy but also broader neurodegenerative changes, such as changes in WM properties and volume.23 A longitudinal study has identified initial ventricular enlargement as a predictive marker for subsequent AD progression and cognitive decline over time.24

We report significant interaction effects of ELS exposure level and age on 3 cognitive outcomes sensitive to cognitive impairment, aligning with existing literature on the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on executive functioning, attention, and working memory.87 Specifically, we demonstrate age-dependent effects of increasing ELS exposure levels on executive function (SWMS), indicating ELS-dependent changes in higher-order cognitive processes with aging. Additionally, younger women with increasing ELS exposure levels exhibited deficits in sustained attention (RVPA), potentially interfering with concentration during tasks. Women with increasing ELS exposure, showed disproportionate memory (PRMPCI) deficits, with increasing age, perhaps reflecting ELS-accelerated age-related decline in memory. Our results corroborate studies reporting memory deficits in adults with ELS exposure31, 88 but show differential changes depending on age. We acknowledge that future studies should formally diagnose MCI using the Mini Mental State Examination. The attenuation of 2 out of 3 cognitive outcomes by low SES aligns with existing literature suggesting that higher SES is associated with access to resources (eg, education and health care) that promote healthy brain aging.89, 90

Our study has several limitations: First, retrospective self-reports of ELS may not be reliable and subject to disclosure or recall biases.91 To address potential disclosure or recall biases, we conducted a comprehensive in-person interview, which allowed for better contextual understanding, increased participant engagement, and more precise examination of ELS features.92 Second, although cross-sectional designs offer valuable initial insights, they inherently lack the temporal dimension of longitudinal studies, and we cannot draw conclusions on aging trajectories within persons.93 However, we used continuous age as a proxy for temporal dynamics, by including the interaction between ELS severity and age in the model. This approach is critical because it addresses a significant gap in human studies regarding the interaction of age and ELS. Outcomes resulting from ELS may follow trajectories that either exacerbate or accelerate with aging. Hence, understanding the impact of ELS severity on later life vulnerabilities necessitates a 2-dimensional analysis of ELS and age, recognizing that this relationship may be nonlinear. Consequently, our statistical models incorporate this complexity to accurately reflect nonlinear interactions between ELS severity and age. Third, a further limitation concerns the fact that we cannot unequivocally discern the nature of the interaction effect because we could not conduct post hoc analyses due to the limited power of our sample. Future research should use larger samples. Fourth, and importantly, our targeted high-risk group approach focusing on women does not allow for detection of sex-specificity of ELS-related mechanisms and disproportionately high vulnerability of women for ELS-related AD relative to men. Expanded research including women and men is needed to determine whether women exhibit specific and disproportionate vulnerability to ELS-related exacerbated brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD. Lastly, our sample was predominantly White subjects, limiting generalizability. Future studies should include generally more diverse samples.

Our study took a conservative approach by excluding individuals with structural MRI abnormalities and those taking anti-dementia medications to strengthen internal validity. These exclusion criteria also inadvertently excluded individuals with manifested neurodegenerative disorders, enhancing the credibility of our findings on ELS exposure and neurodegenerative processes during aging. Additionally, we excluded participants with severe head trauma as diagnosed by trained neuroradiologists. However, we cannot determine whether these injuries occurred in childhood or adulthood. Indeed, inflicted head trauma during childhood, that is, blows to the head or shaking, could affect the results of our study. Such head trauma would be classified as physical abuse. Our study was not designed to assess specific effects of different maltreatment types. In fact, it is a question of paramount importance to scrutinize in the future, whether neuropathological processes after ELS are exclusively explainable by direct neural injury and damage, as inflicted by physical abuse involving head trauma early in life, or whether accelerated brain aging occurs as a function of a broader range of social–emotional stress exposures with consequent neurotoxic glucocorticoid effects and neuroimmune dysregulation across the lifespan.

Although depression and other psychopathologies have been linked to an increased risk of neurodegenerative disorders,94, 95 we emphasize that our study focused on a non-psychiatric, non-patient population, in which rates of depression, anxiety, and PTSD were relatively low. Despite concerns regarding multicollinearity with ELS exposure, adjusting for psychiatric symptoms did not attenuate any observed outcomes. Future investigations should aim to precisely understand the individual contributions of ELS exposure and psychopathology to brain aging processes.

In conclusion, our study provides important insights into the impact of ELS exposure, a highly prevalent risk factor, on later-life neurodegenerative disease risk in women. Our findings reveal distinct nonlinear effects of ELS exposure on 3 brain aging domains that are dependent on age in women. Our results, taken together, suggest that consideration of ELS might be critical in neurological care to identify cases with risk early and to detect early signs of disease in those at risk. Our results suggest a vulnerability of women for ELS-related AD mechanisms and, if further substantiated, may identify women with ELS exposure as a target group for early detection and intervention. Understanding the precise mechanisms, by which ELS promotes the manifestation of later-life neurodegenerative disorders, will be needed for the identification of novel targets and developmental windows for the early prevention and interception of pathological aging trajectories. This may enable an effective mitigation of neurodegenerative disorders, even before symptoms become manifested, based on developmentally informed disease pathways.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NeuroCure Cluster of Excellence (German Research Foundation EXC 257) grant to C.H. and M.E. and the Neuroscience Clinical Research Center. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author Contributions

C.H. and M.E. contributed to the conception and design of the study. C.H., C.B., S.E., L.F., M.B., M.S., R.M., L.K., H.K., M.G., and J.R. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. C.H. and L.F. contributed to drafting the text and preparing the figures. All authors approved the manuscript.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Open Research

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.