Enhancing the Quality of Research Synopsis of International Students Through Peer Feedback: A Case Study

Abstract

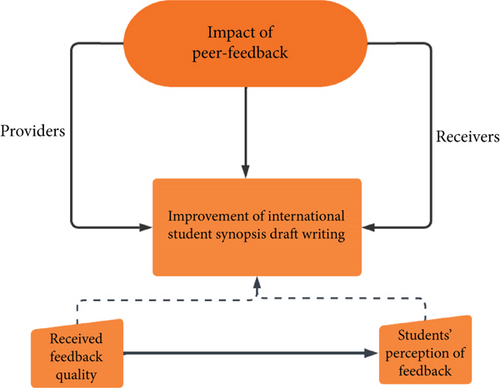

The role of peer feedback in academic writing has garnered increasing attention from educators and research supervisors in recent years. Nevertheless, limited information exists about the perceptions and experiences of international doctoral students concerning the learning outcomes derived from giving and receiving feedback on research synopsis writing. This case study employs a variety of data sources, including research synopsis drafts, written peer evaluations, and semistructured interviews, to explore how 11 junior and seven senior doctoral candidates at Chinese universities benefit from receiving and providing feedback on their peers’ research synopses, respectively. Through the analysis of the interview data, four emergent themes related to student learning were generated through the exchange of peer feedback: (1) enhancing research synopsis writing awareness, (2) progressing in synopsis writing drafts, (3) improving research skills with peer feedback, and (4) fostering reflective and critical learning. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the potential educational opportunities that arise from exchanging peer evaluations in scholarly work.

1. Introduction

The globalization of higher education has significantly increased the diversity of student populations, bringing both opportunities and challenges in pedagogy and research training [1]. In China, this expansion has not only enhanced the diversity within academic programs but has also enriched research output by incorporating diverse perspectives from international students [2, 3]. However, international students face unique challenges, particularly in adapting to different academic cultures, language barriers, and varied educational systems [4, 5]. These obstacles are especially evident in academic writing, where unfamiliar conventions and expectations highlight the need for tailored support mechanisms [6].

Research writing plays a pivotal role in shaping the academic trajectory of doctoral students, with the research synopsis being a key milestone in the early stages of their academic journey [7]. Crafting a well-structured synopsis demands strong research and writing skills, yet many international students struggle with this process due to differences in prior academic training and writing standards. Recognizing these challenges, universities have introduced several interventions, including writing workshops and peer feedback sessions, to improve international students’ research writing skills [8, 9]. These interventions are essential to help students meet the high academic writing demands in globalized educational settings.

In higher education, supervisors are often occupied with their academic responsibilities, such as conferences and research projects, which limits the time they can dedicate to guiding students through the writing process. Furthermore, in countries like China, language barriers can exacerbate communication gaps between supervisors and supervisees, making it difficult for students to receive timely and effective feedback. Some professors may be hesitant to engage deeply with students’ struggles, and students themselves may be reluctant to discuss their limitations openly. Given these challenges, peer feedback becomes an essential alternative for enhancing students’ writing skills and research competencies. This method not only alleviates the workload on supervisors but also provides students with a collaborative environment to refine their work and gain critical perspectives from their peers.

Peer feedback assists students in providing constructive evaluations of each other’s work [10, 11]. By engaging in this process, students not only benefit from receiving feedback but also enhance their own learning through the act of reviewing [12]. Despite its potential benefits, further research is needed to assess how peer feedback can enhance research synopsis writing, particularly among international students with varying academic expertise. This study is aimed at addressing this gap by exploring the effectiveness of peer feedback in improving the quality of research synopses written by international doctoral students in China.

2. Literature Review

Peer feedback, grounded in collaborative learning theory, has been widely recognized as a mechanism that fosters both cognitive and social skills by allowing students to engage in reflective and evaluative practices [13]. Recent studies underscore the importance of feedback that is constructive, argumentative, and well-supported by evidence, as such feedback is more likely to be taken seriously by recipients [14, 15]. Effective peer feedback requires relevance, specificity, logical reasoning, and justification, emphasizing the need for clarity in both the delivery and reception of feedback. According to van den Berg, Admiraal, and Pilot [16], peer feedback serves four primary functions: analysis, evaluation, explanation, and revision. These functions are critical for improving essential aspects of writing, such as content, structure, and style, ultimately enhancing the overall quality of academic work [13, 17].

2.1. Addressing Gaps in Peer Feedback Research

Although a wealth of research highlights the effectiveness of peer feedback in educational settings [13, 18, 19], there remains a gap in understanding its comprehensive impact, particularly in learning processes and cognitive development and its effectiveness in international and linguistically diverse settings [20]. Specifically, there is limited research on how cultural and linguistic differences affect the reception and application of peer feedback among international doctoral students in non-native English-speaking environments, such as China. This underscores the need for further exploration into the role of peer feedback in diverse academic contexts.

Studies suggest that peer feedback can improve writing performance and enhance students’ ability to understand their audience, improve social skills, and engage in constructive criticism [21]. Beyond simply improving document quality [22, 23], peer feedback fosters reflective thinking and deeper engagement with content, which contributes to a broader learning experience [24, 25]. This holistic perspective fills a critical gap in the literature, extending the traditional focus on performance improvement to encompass cognitive and personal growth [26].

2.2. The Dual Roles of Receiving and Providing Peer Feedback

Providing and receiving feedback offers unique learning opportunities for students. When students provide peer evaluations, they can identify issues, become more aware of writing challenges, and acquire diverse revision techniques [24]. This process promotes reflective knowledge construction, enabling students to adopt new perspectives and integrate information into their learning [27]. Research supports the “learning-by-reviewing” approach, indicating that reviewing peers’ work is just as beneficial as receiving feedback [28]. Through this engagement, students enhance their writing and critical thinking skills [29, 30]. However, the extent to which providing feedback enhances writing skills, compared to receiving feedback, remains an area for further research. Moreover, the quality and relevance of the feedback provided are crucial factors in determining its effectiveness [31, 32].

2.3. Students’ Perception of Peer Feedback

Students’ perception of peer feedback plays a critical role in shaping their overall learning experience [33]. Research suggests that students often find reviewing their peers’ work more beneficial for improving their writing than receiving feedback themselves [34]. Engaging in peer feedback broadens their perspectives and fosters the development of critical thinking and writing skills [35]. Additionally, studies show that students who engage repeatedly in peer feedback processes experience greater academic growth and are more likely to retain long-term benefits from their participation [36, 37].

2.4. Peer Feedback in Research Synopsis Writing

Writing a research synopsis is a crucial milestone in a student’s academic journey. International students, in particular, face significant challenges due to language barriers and differing educational backgrounds [38]. Effective communication in research synopses is essential for academic success, and peer feedback plays a pivotal role in helping students refine their writing [39]. Peer feedback can enhance academic writing skills, critical thinking, and adherence to writing conventions [40, 41]. However, the specific impact of peer feedback on research synopsis writing among international doctoral students remains underexplored [30]. Given the linguistic and cultural challenges that international students face, peer feedback provides a means to bridge academic and cultural gaps, helping students overcome these barriers [42, 43].

2.5. Rationale of the Study

- 1.

How do senior doctoral students acquire knowledge and gain advantages by reviewing and critiquing their peers’ research synopsis drafts?

- 2.

In what ways do junior doctoral candidates benefit from receiving feedback on their research synopsis drafts from senior doctoral students?

A key aspect of this research is the application of Van den Berg et al.’s feedback framework for analyzing peer feedback practices. This framework highlights four essential functions of peer feedback: analysis, evaluation, explanation, and revision, which are applied across content, structure, and style in the research synopsis writing process. By integrating this framework, the present study offers a unique exploration of how these feedback functions contribute to developing writing skills among international doctoral students.

3. Theoretical Framework

Before examining the effects of peer feedback on research synopsis writing, it is crucial to define peer feedback and its foundational concepts. Peer feedback involves students reviewing and providing constructive comments on each other’s work, such as research synopses [26]. This mechanism is based on collaborative learning principles, where knowledge is constructed through peer interaction and mutual support [44]. Effective peer feedback includes specificity, relevance, and a supportive tone [13]. The assumption is that both the reviewer and the reviewee are colearners, mutually benefiting from the exchange [45]. This reciprocal relationship enhances critical thinking, self-assessment skills, and a deeper understanding of the subject matter [46].

Boud et al. [47] emphasize that collaborative learning, including peer feedback, is vital for achieving various learning outcomes, such as honing collaborative skills, taking ownership of learning, and deepening subject matter understanding. However, traditional assessment practices often undervalue collaborative efforts, equating them to cheating and promoting harmful competition. To align with collaborative learning principles, this study examines the efficacy of peer feedback in isolation and as an integral component of collaborative learning [48]. The study critically assesses empirical studies on peer feedback, considers its interplay with collaborative learning methods, and evaluates its outcomes, responding to the need for assessment practices that genuinely reflect and encourage collaborative learning efforts.

Theories from various disciplines, including collaborative learning theory, process writing theory, interaction theory in second language acquisition, and sociocultural theory, offer perspectives on how peer feedback can support student learning [49–51]. Peer feedback aligns with Vygotsky’s concepts, including scaffolding, self-regulation, and the zone of proximal development (ZPD) [52–54]. It provides a sociointeractive environment for social support and peer scaffolding [30], enabling mutual learning and knowledge transformation [55, 56].

4. Methodology

The present study used a qualitative approach, focusing on a single case study design. This method allows for a detailed and in-depth exploration of the specific context and conditions of the research subject. Our investigation centred around one particular university, specifically a single department within that university. It was purposively chosen because it actively practices peer feedback as part of its research writing curriculum for doctoral students. Peer feedback is not a common practice across all departments or universities, and this department’s structured integration of peer evaluation in research synopsis writing provided a unique and relevant context for studying its impact. As such, this setting allowed for a rich and relevant data collection environment, enabling us to explore the phenomenon in a natural and well-established practice, aligning closely with the study’s objectives. This targeted approach allowed researchers to gather rich, detailed data from a specific population, providing unique insights into the phenomena under study. A purposive sampling strategy was employed, allowing for the intentional selection of participants who were most relevant to the study’s objectives [57]. This methodology is beneficial when a holistic, in-depth investigation is needed [58].

This qualitative study is aimed at investigating the impact of peer feedback on research synopsis writing among international students enrolled in a 4-year doctoral degree program at a Chinese university. The Faculty of Education encourages student collaboration and feedback on research synopses to improve dissertation writing. This specific feedback process occurs more informally between students or is facilitated by academic advisors on a case-by-case basis. During the first year of their PhD program, the students take courses in their specialized area, and in the second year, they are required to develop a research proposal with the help of a supervisor to fulfill their degree requirements. To finish their doctoral degree, international students must submit a research synopsis draft in English and present it in front of the panel. Upon completing this phase, they submit their polished theses to external evaluators and showcase their finalized projects. This inquiry aligns with the broader supervisor and peer feedback theme in thesis/dissertation writing, as Yu et al. [30] and Zhang et al. [59] explored.

In this study, participants were selected from the 2018 PhD cohort, including all 11 first-year international doctoral students—Ammad, Jabari, Mosi, Imani, Abena, Alex, Ada, Eniola, Borni, Jamila, and Abad—and seven senior doctoral students from the 2017 cohort—Kaira, Alia, Rohan, Abdul, Ray, Ginni, and Diana. Each student, serving as a feedback receiver, was supervised by different professors. In contrast, the role of feedback providers was fulfilled by senior doctoral students. Participants were approached via direct invitations facilitated by the academic supervisors and were informed about the study’s purpose and procedures. Eligible participants were identified based on their enrollment in the relevant PhD programs, and they were contacted through email and in-person meetings.

The sample size was determined by including all students from both cohorts, ensuring comprehensive feedback dynamics between junior and senior doctoral candidates. Data collection was halted after gathering feedback from all participants, as no new themes emerged, indicating that data saturation had been reached. Saturation, in this case, is where no new information or patterns arise from the data [60]. Before submitting the research synopsis, these first-year doctoral students had taken research-oriented core courses and one formal academic English writing training course called “Academic Writing.”

Demographic information about the participants is presented in Tables 1 and 2. To overcome potential challenges in providing feedback, the supervisors advised the participants to partake in peer evaluation exercises before submitting their research proposal drafts for appraisal. The supervisor staff conducted a concise training session on peer evaluation for the participants. Students were instructed to assess overarching and granular aspects of the research proposal composition, encompassing subject matter, idea progression, research methodology, structure, grammar, vocabulary usage, and technical elements. During the research proposal presentations, all the proposed supervisors solicited senior doctoral candidates to deliver precise and valuable feedback to novice international doctoral students, allowing their peers to make additional refinements and improve the overall quality of the research draft. As a result, the 11 synopsis drafts were assessed by senior doctoral students, who provided in-text peer evaluations.

| Students’ ID | Students (pseudonym) | Gender | Nationality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB181 | Ammad | Male | Pakistan | Feedback receiver |

| LB182 | Jabari | Male | Ethiopia | Feedback receiver |

| LB183 | Mosi | Female | Pakistan | Feedback receiver |

| LB184 | Imani | Male | Yamen | Feedback receiver |

| LB185 | Abena | Female | Pakistan | Feedback receiver |

| LB186 | Alex | Male | Russia | Feedback receiver |

| LB187 | Ada | Female | Pakistan | Feedback receiver |

| LB188 | Eniola | Female | Pakistan | Feedback receiver |

| LB189 | Borni | Male | Philippines | Feedback receiver |

| LB180 | Jamila | Female | Pakistan | Feedback receiver |

| LB011 | Abad | Female | Morocco | Feedback receiver |

| LB171 | Kaira | Male | Philippines | Feedback provider |

| LB172 | Alia | Male | Pakistan | Feedback provider |

| LB173 | Rohan | Female | Pakistan | Feedback provider |

| LB174 | Abdul | Male | Pakistan | Feedback provider |

| LB175 | Ray | Female | South Africa | Feedback provider |

| LB176 | Ginni | Male | Philippines | Feedback provider |

| LB177 | Diana | Female | Philippines | Feedback provider |

| Data collection sources | Sampling (participants) |

|---|---|

| Research synopsis draft | First-year doctoral students’ research synopsis draft |

| Peer review feedback(written) | Seven senior students of the doctoral program students |

| Semistructured interviews | Seven senior students of the doctoral program (provider) and 11 students of the doctoral program (receiver) |

We approached a total of 12 first-year international doctoral students and 7 senior doctoral students for participation. Of the 12 junior doctoral students, 11 agreed to participate, resulting in a response rate of 91.6%. One junior student declined to participate, citing discomfort with sharing her feedback and comments from senior students. All senior doctoral students approached for the study agreed to participate, contributing to a 100% response rate from the senior group. The high response rate allowed for an in-depth exploration of peer feedback dynamics within this department. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and they were assured of their right to withdraw at any research stage.

4.1. Data Collection and Analysis

- 1.

Analysis of original research synopsis drafts: Each draft submitted by our international student cohort was more than just a vehicle for peer feedback; it was a mirror reflecting their foundational research competencies. Our analysis, spearheaded by the research team, not only scrutinized these drafts for content, organization, language, and accuracy but also paid close attention to the evolution of these elements in response to peer evaluations. This approach allowed us to measure the tangible impact of peer feedback on the drafts.

- 2.

Evaluation of written peer feedback: The peer evaluations, contributed by seven participants, were a goldmine of criteria and considerations. Our analysis here was twofold: understanding the criteria used by peers in their evaluations and tracing how this feedback translated into concrete improvements in the research synopses.

- 3.

Semistructured interviews with a dual perspective: Recognizing the value of both sides of the peer feedback equation, we conducted in-depth interviews with both feedback providers and receivers. These 18 interviews, each lasting between 45 and 60 min, were structured yet flexible, following a carefully crafted outline (now included in the manuscript’s appendix for clarity). The authors provided rich insights into the participants’ perceptions, experiences, and challenges with the peer evaluation process. The transcribed interviews were meticulously analyzed using Saldaña’s [61] qualitative data analysis model, focusing on coding and thematic analysis.

In applying Saldaña’s model, we employed a detailed and systematic coding scheme, meticulously categorizing responses based on specific criteria such as innovation, clarity, and relevance. To ensure inter-rater reliability, multiple researchers independently coded a subset of the data, after which we engaged in collaborative discussions to resolve discrepancies and reach consensus. This iterative process strengthened the reliability of our thematic analysis. This approach brought precision to our thematic analysis and allowed a detailed examination of the quality of peer feedback, assessing its direct influence on the evolution of the research drafts. Furthermore, a comparative analysis method was employed, involving a systematic cross-examination of data across different participants, which helped ensure coding consistency and enabled a cohesive synthesis of insights. The integration of Van den Berg et al.’s [16] framework was instrumental at each stage, guiding our analysis through its focus on content relevance, structural coherence, and stylistic resonance, thereby enhancing the depth and applicability of our findings.

The analysis in this study followed the framework established by Van den Berg et al. [16]. Applying this framework allowed for a thorough content exploration, ensuring relevance and richness. The focus on structure emphasizes coherent flow and logical progression, ensuring that each section effectively communicates its intended message. The examination style provided that the writing resonated with the intended audience, balancing formality and readability. Together, these themes, rooted in Van den Berg et al.’s methodology, empower us to refine writing in a way that is both comprehensive and transformative, turning mere words into impactful communication. This triangulated approach aimed to uncover patterns and themes that reflected the participants’ educational experiences stemming from their involvement in the peer feedback of doctoral research drafts. The emerging themes from the interview transcripts were coded, and a comparative analysis was conducted to identify recurring issues and patterns. Finally, the data were synthesized by comparing, revising, and integrating themes across all 18 participants’ experiences. This comprehensive approach enhanced the understanding of peer assessment’s impact on doctoral research synopsis development and offered a holistic view of the participants’ learning journeys.

5. Results

The analysis of the 18 international students’ interviews revealed four distinct themes, each shedding light on their experiences and perceptions as providers and receivers of peer feedback on their research synopsis drafts. These insights not only reflect their diverse educational backgrounds but also resonate with the framework of Van den Berg et al., which underscores the importance of analysis, evaluation, explanation, and revision in content, structure, and style (see Table 3). In dissecting the data, special attention was given to differentiating the nuances in the perspectives of those providing feedback from those receiving it. This bifocal approach allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of the peer feedback process by illustrating how each role uniquely contributes to and benefits from the activity. The selected quotes, carefully chosen for their representativeness, vividly capture the essence of the students’ experiences aligned with the identified themes.

| Themes of study | Van den Berg et al.’s functions | Content | Structure | Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enhancing awareness about synopsis writing |

|

Understanding key content requirements. | Recognizing the structure of a synopsis. | Mastering the style and tone appropriate for synopsis writing. |

| 2. Progress in synopsis writing draft |

|

Enhancing the relevance and depth of content. | Improving organizational coherence. | Refining the stylistic aspects for clarity and engagement. |

| 3. Improving research skills with peer feedback help |

|

Developing content-related research skills. | Structuring research effectively. | Cultivating a style that reflects rigorous research. |

| 4. Fostering reflective and critical learning |

|

Applying content knowledge critically. | Structuring learning experiences reflectively. | Adopting a style that encourages critical thinking. |

5.1. Q1: How Do Senior Doctoral Students Acquire Knowledge and Gain Advantages by Reviewing and Critiquing Their Peers’ Research Synopsis Drafts?

5.1.1. Enhancing Awareness of Synopsis Writing

The analysis of the 18 international students’ interviews revealed that engaging in peer evaluations significantly improved their understanding of scholarly synopsis writing. Before participating in the doctoral program, many had limited experience in academic writing and peer review processes. By reviewing their peers’ synopsis drafts, they developed a deeper appreciation and comprehension of the nuances in synopsis writing.

For example, one senior doctoral student noted that despite not receiving peer feedback during their synopsis presentation, their accumulated research experience enabled them to provide insightful critiques. This learning curve fostered significant growth in their ability to write and assess doctoral synopses. Participant Kaira spoke about becoming conversant with a doctoral research synopsis format, and Diana discussed gaining insights into writing an effective literature review. This showed a clear shift in their attention toward the substantive aspects of writing a synopsis.

The textual analysis underlined this transition, revealing a keen engagement by students in the content and structure of the introduction and literature review sections of their synopsis drafts. For instance, in Alia’s evaluation of Mosi’s work, a “thoroughly developed” literature review was praised for its comprehensive content and structured presentation, indicative of a broader trend among participants valuing depth and clarity in academic writing.

5.1.2. Selected Quotes

“The literature review segment was thoroughly developed, examining prior research across various categories, all-encompassing, and lucid.” (Alia peer evaluation for Mosi).

“I genuinely acquired the skill of writing a well-rounded and succinct literature review that portrays the existing research landscape on the pertinent subject, devoid of unnecessary verbiage.” (Rohan peer feedback for Ammad).

5.1.3. Participant Reflections

Abdul shared the challenges he faced in navigating extensive methodologies, particularly those endorsed by renowned authors and those that involved diverse sampling methods. This reflects the complexity of academic research and the need for clear methodological explanations. Ray’s experience offers a different perspective; reading and responding to peers’ synopses taught him the importance of crafting a clear and logical introduction and well-defined research questions. He plans to apply this learning in future research, emphasizing the need to engage with relevant studies and critiques for a structured literature review. A senior student, Kaira, highlighted how her own synopsis writing experiences informed her feedback to others, especially regarding the formulation of research questions and the presentation of empirical data in quantitative studies.

5.1.4. Case Study Integration (Alia’s Example)

Alia’s experience stands out in enhancing awareness about synopsis writing. As a senior doctoral student, she initially faced challenges in understanding the nuances of academic writing. However, through reviewing her peers’ synopsis drafts, she developed a deeper appreciation of the structural and content requirements of scholarly writing. Alia’s reflection on this process, particularly her insights gained from evaluating Mosi’s literature review, exemplifies the transformative impact of peer feedback on her writing capabilities.

5.1.5. Progress in Synopsis Writing Draft

After peer evaluation, senior doctoral students reported notable improvements in the quality of their manuscript drafts. This involved a two-step process: an analysis of the changes made in the manuscripts after peer review and a qualitative assessment of students’ reflections on their writing process. They compared their manuscripts’ initial and revised drafts, noting a marked reduction in grammatical errors and a significant improvement in the flow and organization of ideas in the revised drafts.

5.1.6. Reflective Comments

Mosi’s case was illustrative. In her initial draft, she manually cited studies but struggled with data management in referencing. Based on her peer feedback, she explored and incorporated reference management tools such as Zotero and EndNote, which enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of her citations.

Borni noted the value of peer feedback in fostering a deeper understanding of the writing process, which was instrumental in developing skills for creating well-structured and coherent synopsis drafts.

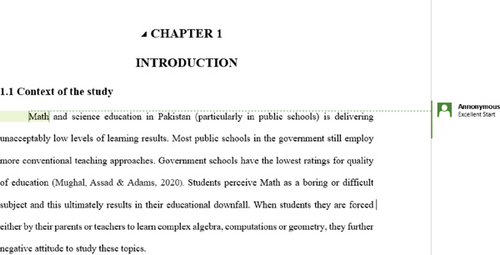

Several participants appreciated the clarity and brevity of their peers’ synopsis drafts. Instead of merely refining linguistic knowledge superficially, the students concentrated on enhancing their academic writing abilities at a more comprehensive level, such as chapter organization, content expansion within the literature review, and the presentation of research questions. Ada noted that she consistently obtained commendations and valuable critiques from her colleagues upon encountering outstanding scholarly compositions. The following passage (Figure 2) exemplifies Alia’s annotation (“excellent”) in the margin of the Microsoft Word file that housed Ada’s summary draft.

“I admire how Mosi articulated the objective of her study. Her writing style offers valuable lessons, as she effectively structured a long sentence by incorporating up-to-date citations. This expression is appealing as it coherently organizes related viewpoints and arguments” (shared by Kaira).

“While working on Ammad’s research synopsis, I realized that all the segments of the research draft must be aligned and have coherence; after reading his work, I updated my final thesis” (second interview with Rohan).

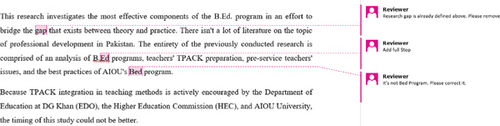

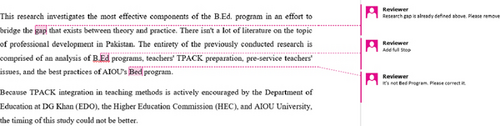

Similarly, Rohan’s review of Imani’s synopsis catalyzed significant refinement of its structure and content. Rohan’s suggestions were directly applied after identifying redundancies in the Introduction section, resulting in a more concise and focused introduction. This change is evident when comparing Imani’s synopsis’s initial and revised versions (see Figure 3). The revised version showcases a shift from lengthy, convoluted sentences to shorter, more impactful ones, clearly delineating the research issues and knowledge gap.

5.1.7. Case Study Integration (Kaira’s Example)

As a feedback provider, Kaira offers a unique perspective on the theme of “progress in synopsis writing draft.” Her insightful comments on Mosi’s study objective testify to her deepened understanding and critical approach to academic writing. Kaira’s ability to provide constructive feedback, as seen in her analysis of Mosi’s work, showcases her grasp of the material and her growth as an academic thinker. Her feedback, which emphasized the importance of clear structure and adequate citation, illustrates the reciprocal nature of learning in the peer feedback process. Kaira’s journey as a reviewer highlights how providing feedback can be an avenue for one’s academic development, reinforcing the theme of progress in understanding and applying complex research components.

5.1.8. Improving Research Skills With Peer Feedback Help

Peer feedback significantly sharpened specific aspects of writing for senior doctoral students, such as the effective use of verb tenses. Abdul’s experience, in particular, highlighted this growth trajectory. As a feedback provider, he not only recognized common language errors in his peers’ synopsis drafts but also acknowledged the critical importance of precision in grammar and vocabulary within scholarly writing.

5.1.9. Quotes and Examples

“As I examined my peers’ research drafts, I better understood the appropriate language used in academic genres. One advantage of peer feedback on research synopsis is that it heightened my understanding of the technical errors in research writing and provided me with alternative research writing ideas.” (Diana).

“My critiques mainly focused on the research inquiries, theoretical elements, and the study’s methodology since I deemed these aspects crucial in my work.” (Kaira).

5.1.10. Case Study Integration (Abdul’s Example)

Abdul’s narrative is particularly illuminating when considering improving research skills facilitated by peer feedback. Faced with the daunting task of navigating complex methodologies, Abdul found clarity and direction through peer feedback. His interaction with fellow researchers enhanced his methodological understanding and allowed him to contribute constructively to his peers’ learning. This interchange in learning and teaching within peer feedback underscores the program’s effectiveness in honing research skills.

5.1.11. Fostering Reflective and Critical Learning

In our study, senior doctoral students observed notable improvements in their understanding and application of academic language conventions, a concept we refer to as “linguistic comprehension in academic genres.” This term encompasses the ability to grasp and effectively employ specialized vocabulary, sentence structures, and stylistic norms characteristic of academic writing. Their experiences suggest peer feedback was instrumental in enhancing this comprehension, producing more sophisticated and well-articulated theses.

5.1.12. Participant Reflections

“In reviewing my peers’ literature presentations, I noted structural inconsistencies. This observation has made me more vigilant about logically arranging various literature sources in my work, striving for a cohesive literature review.”

Ginni’s engagement with peer feedback illustrates the fostering of critical thinking skills. When reviewing work on unfamiliar topics, Ginni concentrated on understanding how peers framed their research questions and supported their arguments. This process not only identified areas lacking clarity but also stimulated introspection on enhancing the connectivity and persuasiveness of their academic writing.

5.1.13. Case Study Integration (Ginni’s Example)

Ginni’s experience further illustrates the development of critical thinking skills fostered by peer feedback. Ginni honed her ability to critically analyze research questions and argumentation when reviewing works on unfamiliar topics. This enhanced her evaluative skills and enriched her academic writing, highlighting the reciprocal benefits of the peer feedback process.

In summary, the significant role of peer feedback in enhancing senior doctoral students’ understanding of synopsis writing in research is evident. The exchange of feedback allowed for a collaborative learning process in which both feedback providers and recipients learned and grew. This process improved their work and contributed to a broader understanding of the content and organizational features essential in research writing.

5.2. Q2: In What Ways Do Junior Doctoral Candidates Benefit From Receiving Feedback on Their Research Synopsis Drafts From More Advanced Peers, Including Senior Doctoral Students?

5.2.1. Enhancing Awareness About Synopsis Writing

Junior doctoral candidates reported significant improvements in their understanding of scholarly synopsis writing through feedback from senior peers. Many junior candidates had limited experience in academic writing, and the feedback process provided them with insights into the conventions of synopsis writing.

For example, participant Kaira, a junior candidate, mentioned how receiving detailed feedback on her synopsis drafts helped her understand the format and structure required for a doctoral research synopsis. Diana, another junior candidate, highlighted the value of senior students’ feedback in improving her literature review section, which she initially found challenging.

5.2.2. Selected Quotes

“Receiving feedback from senior peers helped me understand the structure and essential components of a doctoral synopsis, which I was unfamiliar with.” (Kaira).

“The detailed feedback on my literature review was invaluable. It highlighted areas I needed to expand and helped me structure my arguments more effectively.” (Diana).

5.2.3. Progress in Synopsis Writing Draft

Junior candidates showed notable progress in their synopsis drafts after incorporating feedback from senior students. This progress was evident in improved grammatical accuracy, coherence, and organization of ideas (see Figures 4 and 5). The comparison of initial and revised drafts demonstrated these improvements.

5.2.4. Reflective Comments

Mosi, a junior candidate, discussed how feedback from senior peers led her to adopt reference management tools like Zotero and EndNote, significantly improving her citation accuracy and efficiency.

Borni appreciated the peer feedback for helping him develop a well-structured and coherent synopsis draft. He emphasized the role of feedback in enhancing his understanding of the writing process.

5.2.5. Improving Research Skills with Peer Feedback Help

The feedback from senior peers was instrumental in sharpening specific research skills for junior candidates. This included the effective use of verb tenses, the clarity of research questions, and the alignment of methodology with research objectives (see Figure 6).

5.2.6. Quotes and Examples

“Feedback from senior peers made me more aware of the appropriate language and structure for academic writing, particularly in formulating research questions and theoretical frameworks.” (Diana).

“The critiques I received on my research inquiries and methodology were crucial in refining my approach and understanding the importance of alignment in research.” (Kaira).

5.2.7. Case Study Integration (Mosi’s Example)

Mosi’s experience as a junior candidate receiving feedback highlights the significant role of peer feedback in improving research skills. Initially struggling with citation management, Mosi adopted tools recommended by senior peers, which enhanced her efficiency and accuracy in referencing. This change was evident in the marked improvement in the organization and clarity of her synopsis drafts.

5.2.8. Fostering Reflective and Critical Learning

Junior candidates observed improvements in their critical thinking and reflective learning skills through the feedback process. Engaging with feedback helped them develop a deeper understanding of academic language conventions and the importance of content coherence and organizational structure.

5.2.9. Participant Reflections

Abdul noted that reviewing feedback on his literature presentations made him more vigilant about logically arranging literature sources and striving for cohesive literature reviews.

Ginni emphasized how feedback on her peers’ work, especially on unfamiliar topics, enhanced her ability to frame research questions and support arguments, enriching her academic writing skills.

5.2.10. Case Study Integration (Ginni’s Example)

Ginni’s journey as a junior candidate receiving feedback showcases the development of critical thinking skills. By engaging with feedback on unfamiliar topics, Ginni honed her evaluative skills and improved her ability to analyze research questions and arguments critically. This process not only enriched her academic writing but also highlighted the reciprocal benefits of the peer feedback process. In summary, the feedback from senior doctoral students played a crucial role in enhancing the understanding and skills of junior doctoral candidates in writing research synopses. The process of receiving feedback facilitated a collaborative learning environment where junior candidates could improve their work and develop a deeper understanding of academic writing conventions and research methodologies.

“Engaging in this peer review process has polished us to scrutinize our writing more closely, fostering a more reflective and thoughtful approach to ensuring its quality.”

In summary, the feedback from senior doctoral students played a crucial role in enhancing the understanding and skills of junior doctoral candidates in writing research synopses. The process of receiving feedback facilitated a collaborative learning environment where junior candidates could improve their work and develop a deeper understanding of academic writing conventions and research methodologies.

6. Discussion

This investigation aimed to explore the learning benefits and experiences of both feedback providers and receivers in the context of peer feedback on doctoral research synopsis drafts during the first year of the doctoral program. This study was conducted at a prestigious Chinese university, where the doctoral students engaged in the feedback process experienced academic growth in four key areas: (1) enhancing awareness about synopsis writing, (2) progress in synopsis writing draft, (3) improving research skills with peer feedback help, and (4) fostering reflective and critical learning. The findings extend the theoretical understanding of peer feedback by demonstrating how it fosters both cognitive and metacognitive development, aligning with Vygotsky’s concept of the ZPD and theories of self-regulated learning. Compared to previous findings on peer feedback among doctoral students, the experience reported by the international students in this study displayed more genre-exclusive characteristics. These findings were derived from the distinct nature of the research synopsis genre and the academic learning society within the international student population at Chinese University.

The study showed that academic writing can improve when students give each other feedback on their research summaries. Recent research by Kuyyogsuy [62] and Ono [63] supports this, indicating that peer feedback can significantly enhance academic writing skills by promoting critical thinking and self-reflection. This connection to theoretical frameworks such as collaborative learning theory [47] highlights that the act of providing feedback leads to deeper self-assessment and critical analysis, further reinforcing students’ ability to internalize and apply academic conventions.

This aligns with the findings of Zhang et al. [64] and Huisman et al. [23], who emphasized the learning benefits of reviewing others’ work. Senior doctoral students like Alia demonstrated this growth vividly. Despite not receiving peer feedback initially, their rich research experience enabled them to offer insightful critiques. This phenomenon is also highlighted in a study by Chan and Luo [65], which found that experienced researchers often provide more nuanced and constructive feedback due to their advanced understanding of the subject matter. When international students gave feedback, they were encouraged to find problems and suggest ways to fix them, which improved their academic writing skills and made them better learners, writers, and researchers. In particular, international students became more aware of how to write research papers, and their academic writing skills improved.

The feedback process was a crucible for mastering the conventions of doctoral research synopsis, as seen in the experiences of Kaira and Diana. Their focus shifted significantly toward understanding and improving the substantive aspects of synopsis writing, such as the organization and content depth in the introduction and literature review sections. This insight directly contributes to the theoretical framework of scaffolding, where students, through peer interaction, support each other’s academic progression, aligning with Vygotsky’s theories of guided learning. This shift aligns with observations by Chakraborty et al. [66], which underscore the importance of providing feedback in scholarly writing. The peer evaluations consistently emphasized enhancing content and organization, particularly in the literature review sections [67]. Alia’s appraisal of Mosi’s comprehensive and well-structured literature review exemplifies this focus, resonating with the broader trend of valuing depth and clarity in academic writing, a notion supported by Wei et al. [68].

Study participants demonstrated enhanced adeptness and expertise in soliciting external support following their experiences as feedback contributors. This not only aligns with Liu & Carless’s [44] collaborative learning theory but also supports its practical application in facilitating autonomy in the learning process. For instance, Abdul referred to a guidebook while offering feedback and characterized the experience as a self-teaching process in which he faced obstacles and found solutions. Similarly, Alia and Ginni highlighted self-evaluation and introspection during their interviews. Additionally, they were more analytical and contemplative when composing their dissertations. For instance, Kaira noted that being more aware of language mistakes in her writing was an advantage of giving her peer feedback. Participants such as Rohan underwent a transformative learning experience in which providing feedback honed their synopsis writing abilities. Their journey from confronting challenges in methodology to achieving clarity and logic in their writing mirrors the self-teaching process highlighted by Lu et al. [69].

6.1. In What Ways Do Junior Doctoral Candidates Benefit From Receiving Feedback on Their Research Synopsis Drafts From More Advanced Peers, Including Senior Doctoral Students?

Moreover, those receiving feedback expressed appreciation for the input they were given, which enhanced their grasp of academic writing abilities, such as referring to research texts for a clearer understanding, in the case of Mosi, who, through peer feedback, made significant strides in her manuscript’s technical aspects, such as grammatical accuracy and coherence, as well as in her overall approach to manuscript preparation. This reinforces the theoretical link between peer feedback and metacognitive development, as Wu and Schunn [25] proposed, emphasizing that such feedback processes catalyze self-awareness and academic autonomy.

Such metacognitive progress might have been only partially realized if participants had solely relied on receiving and interpreting feedback from others [70]. In this investigation, obtaining and offering cognitive, metacognitive, and emotional feedback enabled all participants to produce thoughts, feelings, and actions to achieve their learning goals throughout their doctoral studies. For the international students undertaking three to four-year doctoral degrees in this research, the peer feedback experience additionally amplified their metacognitive consciousness and stimulated self-evaluation of their work. This finding contributes to the literature by demonstrating how peer feedback can scaffold self-regulated learning, supporting Vygotsky’s notion of cognitive scaffolding. It aided them in critically analyzing their writing, implementing appropriate modifications, and evolving into more autonomous learners. This deepened our understanding of the connection between peer feedback and the self-regulation of learning processes [68]. Participants such as Borni and Ada demonstrated the broader benefits of peer feedback in academic writing. Their reflections revealed an evolution from focusing on linguistic knowledge to mastering critical components of academic writing, such as argument construction and organization. Recent findings by Wu and Schunn [25] also suggest that peer feedback can facilitate significant cognitive and metacognitive development by encouraging students to engage with their writing and that of their peers critically.

This narrative aligns with the pedagogical implications suggested by Tyndall and Powell [71] and Piccinno et al. [72], emphasizing the role of peer feedback in facilitating cognitive and metacognitive development. Moreover, the experience of senior doctoral candidates such as Ray and Alia in providing feedback enhanced the significance of peer feedback in fostering reflective and critical learning. This finding contributes to the literature by demonstrating how peer feedback can scaffold self-regulated learning, supporting Vygotsky’s notion of cognitive scaffolding. They gained insights into crafting clear and logical introductions and well-defined research questions, which are crucial skills in academic writing. These findings echo the work of Mullard et al. [73] and Drajati et al. [74], who highlighted the role of peer feedback in promoting self-regulation among doctoral students.

6.2. Practical Implications

This study highlights the value of peer feedback as a tool for developing critical thinking and writing skills. Institutions should formalize peer feedback as a regular exercise within doctoral programs, especially in diverse educational contexts with limited supervisory time. Institutions could implement workshops or structured peer feedback sessions to train students on how to give and receive constructive feedback. Supervisors should also be encouraged to facilitate these sessions to ensure they align with academic goals and standards. This process would improve the quality of peer feedback and help doctoral students engage more effectively in self-directed learning. The findings suggest that creating peer learning networks where students can regularly exchange feedback contributes to academic growth. This approach can serve as a valuable supplement to traditional supervisory methods, particularly for international students who may face cultural or language barriers.

6.3. Theoretical Implications

The study reinforces the collaborative learning theory [47] by demonstrating that peer feedback serves not only to improve academic performance but also to foster metacognitive and self-regulatory skills among international doctoral students. This study expands on Vygotsky’s ZPD model by demonstrating that peer feedback, particularly in international doctoral programs, can serve as a scaffold for cognitive growth and adapting to different cultural academic practices. The findings suggest that scaffolding in diverse settings requires more than just feedback—it involves culturally responsive teaching practices. This dimension has been less explored in international, multilingual doctoral contexts, and this research sheds light on how cultural and linguistic differences influence feedback practices. The study suggests that peer feedback can complement and, in some cases, partially substitute for traditional supervision models, especially in contexts where supervisors have limited availability or cultural differences present barriers. This supports broader applications of peer feedback in self-regulated learning and cross-cultural educational environments.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the valuable insights gained, this study has certain limitations that need to be acknowledged. One key limitation is the lack of consideration for background characteristics such as gender, peer feedback literacy, attitude toward peer learning, educational level, and field of study. The literature suggests that the provision and reception of feedback in peer feedback settings may vary depending on these background characteristics. For instance, females may process feedback differently than males [14], and students’ attitudes toward peer learning and feedback literacy can significantly influence how feedback is perceived and utilized [34, 75]. Future research should consider controlling for these variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the peer feedback process.

Additionally, this study relies heavily on self-reported data, which can be subject to various biases. Participants’ perceptions and reported behaviors may not always accurately reflect their actual actions. This discrepancy is a common issue in research that relies on self-reporting, as individuals may unintentionally or intentionally misrepresent their behaviors, experiences, or attitudes. One significant limitation of self-reported data is the potential for social desirability bias, where participants may respond in a manner they believe is more socially acceptable rather than being entirely truthful. Additionally, recall bias may affect the accuracy of the data, as participants might not accurately remember past behaviors or experiences. The literature suggests that self-reported data should be interpreted with caution. For instance, perceptions do not always equate to actions, which can lead to inconsistencies between what participants report and their actual behavior [14]. This limitation must be acknowledged when considering the findings of this study. Future studies could use a mixed-methods approach by combining peer feedback sessions with direct observational methods or integrating peer feedback with automated feedback tools like ChatGPT to assess how AI-enhanced feedback compares to traditional peer evaluations.

Expanding the sample size and exploring different environments, such as other countries or academic disciplines, can help generalize the findings to a broader population and contribute to the broader body of literature in the field. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that ChatGPT can be complemented with human intervention and peer feedback to maximize its effects on education [14]. Incorporating these elements could further enhance the quality and applicability of peer feedback practices.

7. Conclusion

In summary, this study underscores the critical role of peer feedback in developing doctoral students’ academic writing skills. By engaging both as givers and receivers of feedback, students improved their ability to self-regulate, think critically, and reflect on their research. Given the challenges of supervisory limitations, peer feedback offers a viable supplement that fosters collaborative learning and self-directed growth [76]. The results revealed that all the participating doctoral students experienced increased genre awareness and research writing knowledge while also exhibiting development as thoughtful and significant learners and researchers. Several pedagogical implications emerge from this study’s findings. First, since the delivery and reception of peer feedback can stimulate cognitive and metacognitive development, it is advised that academic writing instructors and supervisors incorporate this as a teaching activity in thesis guidance. In countries such as China, where students may encounter language barriers with their supervisors, there are concerns about the accuracy of peer feedback compared to teacher feedback. It may discourage its integration into the thesis supervision process [71]. The present study suggests a need for institutional changes that recognize the value of peer feedback as a complement, not a replacement, for supervisor guidance, reinforcing both collaborative learning and self-regulation theories.

Ethics Statement

This study received ethics approval ZSRT2024193 from the Institutional Ethical Board (IEB) of Zhejiang Normal University. All participants were informed about the purpose of the research and the confidentiality of their personal information. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before their research was conducted. Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw from the study without any consequences. All data collected for this study were anonymized and securely stored to protect the participants’ privacy. The research team adhered to the ethical guidelines and principles set forth by Zhejiang Normal University throughout the study to ensure the responsible and respectful treatment of all participants involved.

Consent

For the present study, informed consent was obtained, and all participants provided written consent. Additionally, the ethics committee reviewed and approved the need for consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.