A systematic review of social research data collection methods used to investigate voluntary animal disease reporting behaviour

Abstract

Voluntary detection of emerging disease outbreaks is considered essential for limiting their potential impacts on livestock industries. However, many of the strategies employed by animal health authorities to capture data on potential emerging disease threats rely on farmers and veterinarians identifying situations of concern and then voluntarily taking appropriate actions to notify animal health authorities. To improve the performance of these systems, it is important to understand the range of socio-cultural factors influencing the willingness of individuals to engage with disease reporting such as trust in government, perceived economic impacts, social stigma and perceptions of ‘good farming’. The objectives of this systematic review were to assess how different social research methodologies have been employed to understand the role these socio-cultural dimensions play in voluntary disease reporting and to discuss limitations to address in future research. The review uncovered 39 relevant publications that employed a range of quantitative and qualitative methodologies including surveys, interviews, focus groups, scenarios, observations, mixed-methods, interventions and secondary data analysis. While these studies provided valuable insights, one significant challenge remains eliciting accurate statements of behaviour and intentions rather than those that reflect desirable social norms. There is scope to develop methodological innovations to study the decision to report animal disease to help overcome the gap between what people say they do and their observable behaviour. A notable absence is studies exploring specific interventions designed to encourage disease reporting. Greater clarity in specifying the disease contexts, behavioural mechanisms and outcomes and the relationships between them would provide a more theoretically informed and policy relevant understanding of how disease reporting works, for which farmers, and in which disease contexts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Voluntary detection of emerging disease outbreaks is considered to be an integral component of emergency preparedness and ‘essential for the timely detection, reporting and communication of occurrence, incursion or emergence of diseases’ [World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), 2021]. Governments may facilitate voluntary detection through various strategies such as developing rapid diagnostic tests, establishing surveillance networks, providing information to farmers and veterinarians and creating dedicated reporting methods such as telephone or internet-based systems (Hoinville et al., 2013). As many of these strategies rely on individuals correctly identifying the clinical signs of disease and then voluntarily taking actions to inform the appropriate authorities, these voluntary animal disease reporting systems need to be culturally appropriate to be effective. Like other aspects of disease control, a range of socio-cultural factors such as trust in government, perceived economic impacts, social stigma and perceptions of ‘good farming’ will influence when, who and how voluntary disease reporting occurs (Gates et al., 2021). Creating effective disease reporting systems therefore requires knowledge of how different socio-cultural factors influence farmers’ and vets’ decisions to report disease. However, understanding these factors requires overcoming significant methodological barriers. For example, retrospective accounts of disease reporting can be compromised by inaccurate recall (Coughlin, 1990; Gilbert et al., 2014) or social desirability bias (Burton, 2004; Krumpal, 2013). Similarly, prospective accounts face the challenge of the value-action gap: the difference between how people describe their behaviour and their observable behaviour (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). Accordingly, this paper has two aims. The first aim is to provide a systematic review of research methodologies used to investigate the social and behavioural challenges facing voluntary disease reporting systems. In doing so, the second aim is to promote discussion on effective methodological strategies to understand the effectiveness of voluntary disease reporting and benefit future research into voluntary disease reporting.

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Defining voluntary disease reporting

In referring to the disease reporting practices of farmers and animal keepers, terminology refers to active and passive surveillance (Hoinville et al., 2013). In relying on farmers and animal keepers to report disease, surveillance systems therefore depend on voluntary behaviour. These voluntary behaviours occur along a chain of activities beginning with observation, discussion and research through to the reporting of suspicious or clinical signs of disease to an official channel or organization (Gates et al., 2021). The outcome of these behaviours is the early detection of disease by the responsible veterinary authority. We therefore define voluntary disease reporting as a process encompassing the autonomous actions of different stakeholders following a disease incursion that results in regulatory authorities being made aware of a potential disease threat. Our particular focus for this review is on the methodologies that can be used to explore what makes farmers who notice clinical signs in affected animals decide to contact their veterinarian or directly notify animal health authorities

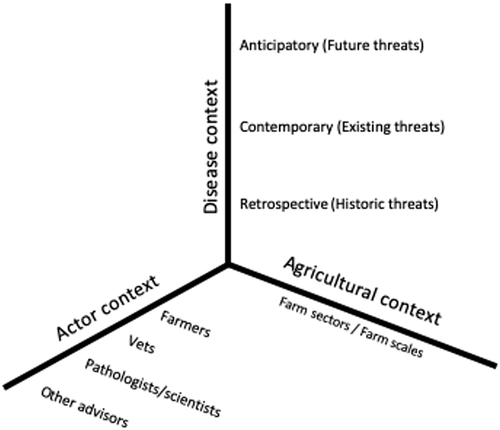

Research on voluntary disease reporting is defined by attention to three different contexts (see Figure 1). First, the actor context refers to the behaviour of specific individuals in the chain of activities. For example, a farmer may report suspicions to his/her vet, other farmers, or farm advisors who may subsequently discuss it informally for advice with other colleagues or refer it to other veterinary authorities as part of a disease reporting system. Second, the disease context refers to the temporal nature of disease reporting research: actors’ behaviour may be discussed in relation to current disease threats, their behaviour in relation to past events or anticipatory actions for future disease incursions. Finally, the agricultural context refers to how responses to disease reporting systems may vary across agricultural sectors and policy regimes.

2.2 Review methodology

- disease AND ‘early detection’ AND animal AND farm* AND decision*

- disease AND reporting OR detection OR surveillance AND animal OR crop AND farm* AND decision* AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SUBJAREA , ‘SOCI’ ) )

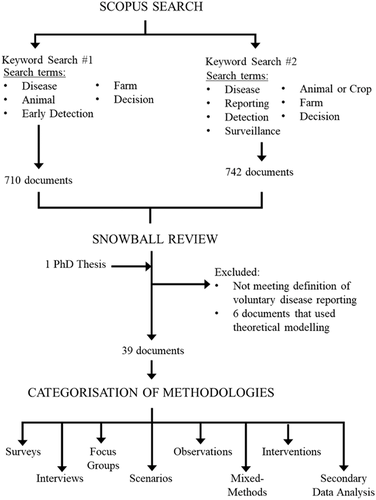

The two searches generated 710 and 742 documents, respectively. Each document in each search was analysed for relevance and removed from the sample where appropriate. As the review focussed on social science methodologies, initial study selection was made by (author 1) to reflect their expertise. Subsequently, all authors assessed whether studies fitted the definition of voluntary disease reporting and were cross-checked with a parallel review undertaken by author 2 reported elsewhere (anonymized reference). This led to the exclusion of studies where they focused on generic biosecurity preventive behaviours. Studies were included where they conformed to our definition of disease reporting systems and any of the disease contexts described in Figure 1.

Studies were not limited to farmers or past disease outbreaks. Literature searches focused on the social scientific literature, but this did not preclude social scientific studies published in mainstream veterinary journals (e.g. Preventive Veterinary Medicine). Thirteen additional documents were added following a process of ‘snowball reviewing’ (Greenhalgh & Peacock, 2005): using Scopus, citations of the most highly cited and relevant documents identified in the initial reviews were analysed and included where relevant. In addition, one relevant unpublished PhD thesis was included in the list of documents. Grey literature was not included in the review: Scopus does not contain unpublished policy reports and snowball reviewing did not identify any additional unpublished studies to include.

In total, 39 publications were included in the review which either used social research methods (e.g. interviews, surveys) to analyse farmers’ behaviour, or analysed secondary data to explore the impacts of policy changes to farmers’ decisions (results of the review are shown in Appendix Table A1). Thirty-two exclusively focused on the subject of reporting disease incidence. A further six papers were included that explicitly mentioned disease surveillance and disease reporting in the paper's abstract, but also provided information on other biosecurity activities. Finally, one paper was included that referred to an on-farm disease alerting system. Six papers were identified employing theoretical or conceptual modelling to explore the effectiveness of financial rewards and penalties. As these are conceptual in nature and do not rely on social research methods, they are excluded from the final analysis. Five papers dealt with crop or plant diseases. These were retained because they conformed to the definition of voluntary disease reporting, their methods were relevant to animal disease and the underlying behavioural mechanisms are similar.

The quality of studies was not adjudicated prior to inclusion. The majority of studies provided a high-level of detail when describing the social research methods used in the study. All studies provided details on the number of research participants: the range varied considerably (from 5 to 1140) reflecting the varied demands of different research approaches. Methodological details tended to be more specific when identifiable conceptual frameworks were used. For many other qualitative studies, however, methodological description was limited to broader descriptions such as pointing to the topics discussed in focus groups or interviews, rather than the precise wording of the questions.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Disease reporting contexts

For the actor context, most papers (29) focused on farmers. Of these, 20 were exclusively focused on farmers with 2 focussed on smallholders. Other papers examined farmers’ views alongside other food chain actors including veterinarians (4), food processors (1) and farm advisors (2). Five papers focused exclusively on vets and disease reporting and a further one examined vets and policy actors’ views.

For the agricultural context, nine publications examined disease reporting in all forms of livestock. Eight studies analysed disease reporting in the cattle sector. Six studies focused on pigs. Studies of disease reporting in sheep were less common: two papers exclusively focussed on sheep and another examined sheep and cattle disease reporting together. Poultry accounted for three papers. The review found two in the aquatic sector, one study relating to equine disease reporting, one for bees and two for crops. In relation to the disease context, most papers (26) did not distinguish between different diseases, of which nine did not distinguish between livestock sectors. Most papers (29) examined actors’ responses to endemic disease outbreaks: no studies examined disease reporting systems that had contributed to disease eradication. Ten papers were explicitly oriented towards finding out actors’ intentions towards future disease threats, whether these were diseases where there had been previous outbreaks (such as foot-and-mouth disease) or none recorded (such as varroosis).

3.2 Descriptive summary of methodologies

Most of the publications included in the review (26) used only one research method with the remainder employing a ‘mixed methods’ (Ivankova et al., 2006) research design. The most frequently used method was interviews (20) followed by surveys (18) and focus groups (9). Eleven studies exclusively used a survey (whether it was online, postal, using the telephone or in person). In addition, six other studies used a survey alongside other methods. Methods are equally distributed across different subjects and sectors. Studies that focused on all diseases across all sectors did, however, exclusively use survey methods. The following sections provide further details on these methodologies and how they have been employed to understand disease reporting.

3.2.1 Surveys

Studies relying on survey methodologies employ a range of different approaches. Some rely on open-ended or generic survey questions collecting information on practices and knowledge, while others rely on more advanced conceptual frameworks that collect quantitative data using Likert-scale questions for advanced statistical modelling. Examples of the former include two papers by Hammond et al. (2016a, 2016b) investigating whether a high priority pest would be reported to the Australian crop disease surveillance programme. These surveys point towards gaps in knowledge in surveillance programmes and respondents’ confidence in their ability to correctly identify plant pests. Similarly, Guinat et al. (2016) study on disease reporting in pigs in the United Kingdom uses a range of questions relating to respondents’ knowledges and perceptions, showing that farmers with low levels of knowledge, concern and awareness of African Swine Fever are less likely to report it (see also Hernández-Jover et al., 2016).

Other studies have attempted to operationalize frameworks such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour or Health Belief Model using structured surveys with Likert-type response scales, followed by quantitative analysis and modelling. For example, Palmer, Sully, et al. (2009) study of disease reporting is informed by aspects of the Health Belief Model (HBM) which emphasize the role of perceived risks, barriers to reporting, trust, control beliefs and self-efficacy, position within the community and attitudes towards surveillance. Wright et al. (2018) rely on the Theory of Planned Behaviour to analyse intentions to report disease among Australian livestock producers to either the Government or private vets. Similarly, Pramuwidyatama et al. (2020) survey instrument is based on the theory of planned behaviour in order to quantitatively analyse motivations of broiler farmers to prevent Avian Influenza. The study shows that farmers responding to the survey tended not to be ‘aware’ of the clinical signs of HPAI; hence, only severe HPAI outbreaks will be reported. As a result, information about HPAI is less obvious and ‘trustful’ (p. 7).

Structured questionnaires have also been used to compare reporting behaviours between farmers according to their exposure to disease. Gilbert et al. (2014) use a survey of 69 cattle farmers to assess factors associated with farmers’ decisions to submit biological samples as a means of identifying early stages of infection. The survey posed two different kinds of questions to farmers: first, ‘prospective assessment’ in which farmers were asked how often they performed specific actions, and second, ‘retrospective assessment’ in which farmers were asked to recall specific events over the last 6 months. Analysis revealed that farmers prospective assessments generally overestimate actual disease reporting. In addition, farmers were asked questions about their attitudes and motivations towards veterinarians and disease surveillance. Results also indicated that farmers who were members of herd health schemes would be more likely to submit samples. Likewise, Randrianantoandro et al. (2018) use a questionnaire survey of 201 pig farmers in Madagascar about African Swine Fever (ASF) in order to analyse their responses to financial compensation. Their results show that as compensation increases, more farmers are willing to report ASF cases but this also depends on farm-related characteristics, farmers’ knowledge about ASF, administration of the classical swine fever vaccine and previous experiences with ASF.

Other studies combined structured and open-ended questions within a survey to explore and explain differences in farmers’ disease reporting practices. Lupo et al. (2014) adopted a retrospective case-control design in which 27 non-reporting and 89 reporting farmers were surveyed by telephone using this approach. Analysis of farmers’ reasons for not reporting disease, such as the absence of compensation, is illustrated both quantitatively and qualitatively using quotations from open-ended survey questions. Separate quantitative modelling is conducted to show how different factors (such as farm size, prior receipt of financial compensation) are associated with farmers who have reported disease and those who have not.

3.2.2 Interviews

Although interviews are a popular method to explore disease reporting, the studies reveal a diversity in approaches. Face-to-face interviews can be used to collect objective information, but as this information could be collected by a questionnaire, the value of interviews lies in using qualitative semi-structured approaches to explore in-depth phenomena such as behaviour and decision-making. For some studies in the review, detailed methodological descriptions are provided, but in others interview topic guides, questions and approach are not provided (Garza et al., 2020; Palmer, Sully, et al., 2009). Where studies looked at reporting for all diseases across a sector, interviews took a broad approach, often not directly referring to disease reporting. For instance, the open-ended interview schedule in Fox et al.’s (2020) study of shellfish in Northern Ireland covers a range of biosecurity related issues and enables the authors to report generic attitudes and behaviours pertaining to disease reporting. From this, Fox et al. (2020) report how farmers’ perceptions of stress, predation and luck mean that dead oysters are not reported and thrown away despite requirements to report them. Similarly, two studies by Sawford et al. (2012, 2013) examined veterinarians’ decision making about diagnostic submissions in Canada and Sri Lanka. Both studies employed the same open-ended interview schedule that revolved around pre-established key themes, such as decision making around laboratory submissions and participation in disease monitoring.

Interview methods were more specific where they examined specific diseases or practices. For example, Bronner et al.’s (2014) study analyses why farmers do not report abortions in relation to brucellosis control. First, their research design seeks to differentiate respondents between areas of recent and historical outbreak histories. Second, their questions are specifically directed to understanding abortion as an indicator of disease, and farmers’ relationships with the surveillance system. Thus, interviews focused on farmers’ own definitions of abortion and their knowledge of surveillance systems.

‘As you know, I'm interested in how farmers make decisions to send or not send carcasses or fetuses to the lab. Can you tell me the story of when it happens that an animal dies on the farm?’

In McFarland et al.’s study, participants with different levels of engagement with the surveillance system were selected: some were regular submitters, others occasional and the remainder who had never submitted any samples. McFarland et al.’s (2020) study sample was relatively small (five BNIM interviews were conducted), but it can be used with more respondents if necessary (McFarland et al.’s study also used focus groups). Other studies of tree health by Porth et al. (2015) provide a similar historical narrative to understanding disease reporting. These methods allow the authors to trace the network of actors involved in the reporting and management of an outbreak of Asian Longhorn Beetle (ALB) in Kent, England. In tracing this history, the study is able to provide details on the reasons why the outbreak was discovered. Although detailed interview methods like the BNIM are not referred to in the paper, this detailed retrospective social network approach provides a potentially more useful research design compared with interviews with people who have not encountered disease.

3.2.3 Focus groups

Three studies in the review exclusively used focus groups to analyse disease reporting. First, Robinson and Epperson (2013) and Robinson et al. (2012) use focus groups to explore disease reporting practices among private vets in Mississippi (US) and Northern Ireland (UK). Both studies broadly adopted the same approach in which general questions about the decision and process of sample submission was discussed. The subsequent discussion elicited a range of factors that influenced sample submission, which were both social and technical. For example, veterinarians reported that farmers had become keener to submit samples but this depended on the social characteristics of farmers. Veterinarians also pointed to technical challenges of sample submission, such as health and safety issues, inadequately packaged samples and biosecurity issues associated with transportation. Importantly, the focus groups also highlighted how the relationship between veterinarians and pathologists was an important part of the reporting process. Pathologists were not included in this study, nor do they appear to be part of other studies.

3.2.4 Using scenarios

For both qualitative interviews and quantitative survey methodologies, scenarios were used as a means of eliciting participants’ intentions towards disease outbreaks. Scenarios represent a helpful methodological device to stimulate thinking or challenge preconceptions and to examine the causes and consequences of what may happen in future (Quine et al., 2011). They are likely to work best when they are plausible (Oreszczyn & Carr, 2008), developed consensually (Oreszczyn et al., 2010) and apply to a specific purpose (van der Heijden, 1996). Bradfield et al. (2005) suggest scenario methodologies work best in relation to four purposes (making sense of puzzling situations, developing strategy, anticipation and adaptive organizational learning) all of which apply to voluntary disease reporting. In health psychology, scenarios are referred to as vignettes, which may take the form of text, pictures or video (Hughes & Huby, 2002) and used to elicit attitudes and beliefs about complex and potentially sensitive situations (De Bruyn et al., 2020). Nevertheless, where they are poorly designed and/or executed (see Gould, 1996), vignettes may fail to capture the reality of people's lives, limiting their generalizability (Hughes & Huby, 2002).

‘Imagine that more than 40% of your pigs are sick with clinical signs as suspected cases from one of the three notified diseases (PRRS, FMD, and CSF). Your sick pigs did not respond after 3−5 days of treatment and the live weight of fattening pigs ranged from 20 to 50 kg. Choose one of the following options related to disease reporting to report swine disease in your holding to veterinary or local authorities’.

Pham et al. (2017) conclude that the most important factors in reporting are the type of culling implemented and the likelihood (as opposed to the amount) of receiving compensation. Importantly, the choice-sets relied on a scenario to generate responses. Delgado et al. (2014) also use scenarios in their analysis of intentions to report foot-and-mouth disease among cattle producers in the United States. Their study used a two-stage research design in which two surveys were returned by the same respondents over a 6-month period with a different scenario in each. This approach allows Delgado et al. (2014) to show how disease reporting intentions and perceptions are linked to different disease scenarios.

In qualitative research, Pfeiffer (2018) utilizes a scenario-based approach to explore disease reporting. Three hypothetical scenarios were presented to farmers which were preceded by a general discussion about biosecurity issues and use of veterinary services on farms. Scenarios were presented alongside a picture of a sheep farm, although the picture was not relevant to the scenario itself. Following the discussion, focus group participants were asked to rank the barriers and incentives in order of importance. Results from the focus groups revealed the importance of context, which was defined as farmers’ sense of self as a sheep farmer. This meant that self-reliance was a key strategy in resolving any problems rather than contacting a veterinarian which would happen when they had reached the limit of their knowledge and experience. Other qualitative studies using scenario methods include Hamilton-Webb et al. (2016) who use three scenarios to elicit participants’ views on disease reporting under different contexts and policy environments. In their case, the scenarios were co-developed with the UK government department responsible for disease management, although such co-production of realistic scenarios could involve a wider range of relevant participants. The scenarios used reflected different compensation options, and participants were asked opinions of the likely reactions to the scenario.

3.2.5 Ethnographic observation

One study used ethnographic methods to examine farmers’ disease reporting practices. While ethnography uses a range of methods such as interviewing (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019), it is often associated with different forms of observation. For example, in Phillips's (2020) study of beekeeping and potential infestation with varroa mite, interviews with beekeepers and policy officers were accompanied by participant observation at meetings, events, field-days, club beekeeping and training. Research activities were also spread over a period of 7 years. The longitudinal and observation focus allows Phillips to show how a sense of anticipation and ‘good beekeeping’ is created as a means to encourage early reporting of signs of varroa mite infestation.

3.2.6 Mixed methods

Mixed methods refer to the use of a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to capitalize on their respective strengths (Creswell & Clark, 2017). The approach allows small-scale research (such as semi-structured interviews) to sequentially inform methodologies (such as surveys) used on a larger scale (Ivankova et al., 2006). Alternatively, different forms of data can be triangulated to provide ‘convergent validation’ (Fielding, 2012). A third of the studies (13) used a combination of methods, such as semi-structured interviews and large-scale quantitative surveys. Examples of sequential mixed methods designs included Delgado et al. (2012, 2014) who used semi-structured interviews to design a structured survey based around the Theory of Planned Behaviour. In this study, the aim was to examine farmers’ likely reactions to an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in Texas, USA. Telephone interviews were initially used to understand respondents’ knowledge of FMD, before being asked to comment on the feasibility of an outbreak scenario. As such, participants were drawn from a range of public and private organizations that would be involved in outbreak management. Subsequently, a survey instrument was developed based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour and the results from the telephone survey, which was subsequently evaluated and modified during a 2-day workshop. In doing so, it highlights the importance of mixed methods when researching disease reporting.

Other studies that used this sequential mixed methods approach included two studies by Elbers et al. (2010, 2010) that analysed farmers’ disease reporting behaviours for classical swine fever and avian influenza. The first study on avian influenza analysed poultry farmers’ and veterinarians’ reporting practices employing focus groups, semi-structured interviews and lastly an electronic survey. The focus groups and interviews involved farmers and veterinarians and highlighted a range of different themes relating to the failure to report disease and identified potential solutions to disease reporting barriers. Finally, a structured survey focused on the conditions required to report a suspicious case, barriers to reporting and the respondents’ feelings and economic consequences of reporting a suspicious incident. Other mixed studies began with quantitative methods. For example, Hernández-Jover et al. (2016) used results from a postal survey of 919 Australian farmers to select interview participants by stratifying farmers according to demographic and husbandry practices. Limon et al. (2014) used a survey containing projective questions such as asking what would ‘most people in the community do if almost all their animals die within one week?’ The results were subsequently discussed at focus groups and interviews.

3.2.7 Intervention studies

Four studies sought to analyse disease reporting practices by analysing a specific intervention or policy change designed to help farmers and other stakeholders submit samples or report suspected disease. Rao and Zhang (2020) use a natural experiment of different insurance regimes in the pig industry in China. Using a structured in-person survey, results showed that insurance was associated with an 18.2% increase in likelihood of reporting diseased animals, but that insurance also acted as moral hazard increasing pig mortality (see Zhang et al., 2016). Struchen et al. (2016) provide an example of an intervention study examining the use of a disease reporting tool developed to be used by mobile devices. The application was designed to collect disease information on equine diseases and can be used only by registered ‘sentinel practitioners’, that is, equine veterinarians. The study analysed disease reporting using the application and found that disease reporting continued to increase compared with previous years. Telephone interviews with participating veterinarians explored motivations for using the application, reasons for low levels of reporting and the use of reporting devices. Low reporting was connected to disease absence, technical difficulties and lack of benefits. In contrast, Beyene et al. (2018) compared disease reporting among 12 final year veterinary students, six of which were provided with a smartphone application. Comparing the two groups revealed that the smartphone group reported disease faster than those without it, although delays were encountered due to poor cell-phone reception.

In the management of tree health, mobile applications and citizen-science approaches have proved a popular way of enhancing disease surveillance. In the United Kingdom, the ‘Observatree’ initiative has been analysed by Crow et al. (2020) and Hall et al. (2017). The Observatree initiative is a programme of activities designed to give people interested in tree health the skills and resources to identify priority tree pests and diseases, thereby enabling them to report them. For this project, tree health data were submitted online which are then shared with relevant authorities such as government pathologists and entomologists. Other initiatives in other countries follow a similar procedure. For example, the LIFE ARTEMIS project in Slovenia used a mobile application called ‘Invazivke’ to allow diseases to be easily reported (Crow et al., 2020). Evaluations of these projects have focused on the aims, motivations, educational outcomes and reporting practices of those volunteers involved to understand their motivations and tracking the social outcomes (Hall et al., 2017).

3.2.8 Secondary data analysis

One study used secondary data analysis to analyse the influence of veterinarians and other local stakeholders on farmers’ disease reporting habits. Bronner et al.’s (2015) study relies on observable behaviour as a way of avoiding the bias common to farmers’ stated preferences/behaviours found in other studies (e.g. Gilbert et al., 2014). Such analyses are of course limited by the availability of data, and the data itself: attitudinal, motivational and other social factors are not routinely collected so these analyses cannot incorporate them. Bronner et al.’s study compares the number of veterinarians in specific regions of France to levels of disease reporting by farmers. Results show that while disease reporting significantly varies between agricultural sectors and herd sizes, so does the size of veterinary practices in each area. Specifically, in areas where veterinary practices had more than one veterinarian, farmers were more likely to report disease. The absence of other contextual data poses limitations to this analysis. However, where these data exist, they may be utilized to explore the relationships between structural constraints to disease reporting and the role of the veterinary profession.

4 DISCUSSION

This review has highlighted the range of social science methods used to investigate behavioural factors associated with the voluntary reporting of animal disease. The range of methods used is unsurprising given that disease reporting involves a range of activities involving different actors, and which allows research questions to be posed in a variety of ways. Some methods may be better suited to answer some of these questions than others. For example, understanding how farmers make sense of what counts as a suspicious disease and the thresholds for reporting may be best derived from in-depth qualitative methods such as focus groups, interviews and observation. Where studies are attempting to estimate the effect of different behavioural interventions or capture information at scale about farmers’ behaviour, quantitative methods are more likely to be relevant. At the same time, however, the familiarity of these methodological approaches also points towards specific improvements and innovations that could be used to improve understandings of voluntary disease reporting. These are discussed in turn below.

First, a significant challenge facing studies of voluntary disease reporting is using methods that elicit accurate statements of behaviour (Gilbert et al., 2014), rather than those that reflect desirable social norms (Burton, 2004). In fact, beyond comparing subjective accounts with objective reports (see Gilbert et al., 2014), no studies in the review seek to compare these objective and subjective reports, or provide significant new insights into how to overcome the gap between values and actions. The use of prospective questions that are framed in relation to the action of others (such as good or bad farmers, neighbours or specific contexts) can potentially help to overcome issues of social desirability bias. However, many of the studies in the review lack detailed information on their precise question wording making it difficult to ascertain whether this approach has been used. Other approaches such as the biographical narrative approach used by McFarland et al. (2020) may also be useful given their reliance on more general and open-ended questions which allow the respondent to tell their own story, situate it within their own context and validate their own experiences.

The use of scenarios is another way in which to explore farmers’ intentions in non-judgmental ways (Soleri & Cleveland, 2005). While the review found several studies that used these approaches, there is potential to adapt how they are used. In other studies, participatory and interactive scenarios have been used, allowing participants to dynamically and recursively map key issues in discussing their own and others’ responses to a given situation (Oreszczyn & Carr, 2008). For example, Khan et al. (2020) developed a card game to explore support for different regulatory approaches to anti-microbial resistance. This game involved a simple card-sorting exercise in which participants were asked to associate actors with specific characteristics. Similarly, Maye et al. (2017) use an influence mapping exercise in which participants were asked to identify a range of biosecurity ‘influencers’ and place them on concentric circles to indicate their importance to them in different biosecurity scenarios. These interactive methods combined with scenarios can potentially make a greater methodological contribution to understanding disease reporting.

Other innovative methods have been developed in order to address the methodological challenges of the values-action gap, particularly where the actions are controversial or test social expectations. For example, the randomized response technique (RRT) is widely used in research relating to behaviours that may be illegal or on the boundary of illegality and appropriate conduct (Lensvelt-Mulders et al., 2005). When using the RRT, the question-answer process is subject to a randomizing device (usually a device) which indicates whether the respondent should answer the question truthfully, or whether pre-determined answers (such as yes or no) are recorded. As the randomizing device is not visible to researchers, the process provides the respondent with a sense of security when providing answers that may be incriminating. In agricultural studies, this method has been used to assess the level of illegal wildlife culling (Cross et al., 2013). Other more complex games may also be used to simulate disease reporting behaviours. For example, Merrill, Koliba, et al. (2019) (Merrill, Moegenburg, et al., 2019) developed a biosecurity computer game to examine how rewards and penalties influenced whether biosecurity actions were taken (such as showering before entering a biosecure pig unit). While these games simulated behavioural responses in disease management, arguably they can help distance the participant from more formal research settings which appear as ‘accountability settings’, which are more likely to elicit socially desirable behaviours.

Second, another way of dealing with the values-action gap is through different research designs, such as the comparative approach used by Lupo et al. (2014). However, the fact that the review finds only one study explicitly employing a case-control research design suggests limited methodological innovation in approaching this challenge. While other studies, for example Bronner et al. (2014), Kuchler and Hamm (2000) and Rao and Zhang (2020), try to account for disease incidence by conducting research in different areas or take advantage of changes to long-term policies, other methodologies and research designs should be employed to assess farmers’ behaviour. The use of mixed methods may also help in this respect, either by allowing triangulation of different data sources, or using one method to construct culturally relevant and meaningful survey questions, and/or identifying and selecting appropriate research participants. While some studies used this approach (Delgado et al., 2014; Elbers et al., 2010), there is potential for greater use of a mixed methods design in future studies of disease reporting.

Another way of managing the challenge of the values-action gap is through studies of interventions designed to improve voluntary reporting of disease. However, it was surprising to find few studies of specific interventions seeking to improve disease reporting. Some studies such as Struchen et al. (2016) examined the role of mobile apps, but there were no examples of controlled trials of different interventions. Elsewhere, other studies have analysed the use of on-farm sensors used to alert farmers of potential health and welfare problems in livestock (Bruijnis et al., 2013; Eckelkamp & Bewley, 2020; Mazrier et al., 2006). As the potential of sensors and other wearable technologies increases, such interventions may become more relevant to unexpected and exotic diseases. However, the promise of technological fixes suggested by the emergence of smart agricultural technologies may be compromised by social and economic dimensions of farming affecting their adoption (Rotz et al., 2019). Unless there are unpublished studies of interventions designed to improve disease reporting, the review indicates a sizeable research gap that can be filled by future intervention studies.

Finally, the review also suggests the need for greater theorization of how disease reporting ‘works’ and can be improved, particularly given the potential for intervention studies. Approaches to policy evaluation stress the need for studies to be organized around a ‘theory of change’ which conceptualize how policies should work. For Pawson and Tilley (Pawson & Tilley, 2004; Pawson et al., 2005), a theory of change should encompass the relationships between contexts (C), mechanisms (M) and outcomes (O). Understanding the CMO relationship, they argue, is crucial to understanding what works for whom and how. Adopting this approach to analysing disease reporting could offer significant advantages, not least because existing studies often elide different contexts and ways disease reporting works, and multiple outcomes. For example, the review found that in many studies, disease contexts and agricultural contexts are combined meaning the specificity of contextual influences is lost. Indeed, the majority of papers had no specific focus on any particular disease. Even where studies have analysed a range of diseases, there remains a need to understand the interactions between different diseases and control efforts: are farmers’ attitudes towards disease control for one disease the same as others he/she faces, and is so why does this occur? This question is not adequately answered in the studies in this review, which instead seem to conceptualize farmers as having universal responses to disease rather than diseases. In this sense, this review suggests the need for further contextually specific studies both in terms of the diseases analysed and the agricultural sectors involved.

Alongside context, mechanisms refer to specific behavioural responses that are in some way triggered by an event, intervention or policy. Mechanisms therefore reflect an identifiable pattern of action that can be analysed in some way. In Pawson and Tilley's terms, mechanisms are therefore not the policy itself, but in terms of disease reporting, reflect farmers’ responses and causal motivations. Pawson and Tilley suggest that not only should policies be based on these likely causal mechanisms, but that also policy evaluation should be based upon them. Where they are not explicit, researchers should estimate how policies are seeking to have a behavioural influence. Maye et al. (2020) provide an example of how mechanisms operate in animal health, identifying ‘seeing is believing’ as a mechanism to promote vaccine acceptability and confidence. By involving farmers in the process of wildlife vaccination, allowing to see it being conducted and its uncertainties managed, this mechanism should lead to outcomes of increased confidence in vaccines.

While this approach can help understand how and for whom animal disease policies and initiatives work, this review finds a very narrow focus on specific behavioural mechanisms, if at all. For example, Bronner et al. (2015) connect larger veterinary practices with increased disease reporting, but the precise causal mechanisms for this is unclear: does contact with a greater variety of vets promote greater social responsibility, and if so why? The extent to which these behavioural mechanisms are evaluated is not present in this or other studies. One exception is Hall et al.’s (2017) analysis of the Observatree project whose analysis implicitly considers how developing social capital and a shared sense of responsibility can contribute to disease reporting. Phillips's (2020) study of potential infestation with varroa mite also highlights how a ‘sense of anticipation’ is crucial to disease reporting and can be created by various organizations and activities.

Where studies do focus on behavioural interventions – specifically the role of compensation – their evaluation causal mechanisms are nevertheless limited. These studies tend to focus on farmers as economic maxmizers, that is the provision of compensation will promote behavioural responses that are consistent with maximizing profit. Studies of the effects of changes to compensation regimes such as Kuchler and Hamm (2000) make no attempt to unpack the varied motivations and mechanisms by which farmers respond to financial incentives. As studies in the review show, other social factors are also likely to shape these responses. However, studies in the review that explicitly analyse these factors – whether qualitative attempts to examine the role of self-identity or in surveys employing the theory of good farming – are largely focused on farmers’ intentions, rather than their actual behaviour.

Contexts and mechanisms when correctly aligned should promote specific outcomes. Where papers in the review refer to outcomes, they relate to whether a disease is reported or not, and/or speed of reporting (e.g. Beyene et al., 2018; Struchen et al., 2016). However, other studies in the review show, there are a range of social factors that influence the decision to report disease or not (e.g. Bronner et al., 2014; McFarland et al., 2020; Palmer, Fozdar, et al., 2009). It is therefore likely that attempts to influence disease reporting will also need to have other social outcomes in order to function efficiently. This is clearly shown in the analyses of citizen-science approaches to disease reporting whose success is dependent on the social capital generated by the activities they encompass (Hall et al., 2017). Methodologies used to evaluate disease reporting initiatives – as well as the interventions themselves – therefore need to be sensitive to these broader social outcomes to understand how and whether disease reporting works.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper presents the results of a systematic review of the methodologies used to investigate behaviours towards voluntary animal disease reporting. While early detection of disease is a key element of a successful disease surveillance and control programme, the review finds relatively few (39) published academic studies, some of which cover a range of different diseases and livestock sectors. The review finds a broad range of methodological approaches, involving both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Methodological quality appears to be high, but a key recommendation for future studies is to provide a greater level of methodological detail, such as the precise question wording used in personal interviews and focus groups. Moreover, there is scope to further methodological innovations to study the decision to report animal disease to help overcome the gap between what people say they do and their observable behaviour. A notable absence is studies exploring specific interventions designed to encourage disease reporting. Greater clarity in specifying the disease contexts, behavioural mechanisms and outcomes, and the relationships between them would likely provide a more theoretically informed and policy relevant understanding of how disease reporting works, for which farmers and in which disease contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to the Ministry for Primary Industries for supporting this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the ethical policies of the journal, as noted on the journal's author guidelines page, have been adhered to. No ethical approval was required as this is a review article with no original research data.

APPENDIX A1

| Publication | Primary Method | Other methods | Disease context | No. participants | Methodological details | Diseases | Sector | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fox et al. (2020) | Interviews | Retrospective | 16 | Interview schedule is provided | All | Aquatic | Farmers and processors | |

| Lupo et al. (2014) | Interviews | Retrospective | 116 | Case-control study design – interviews with farmers who have reported in the past and those that are currently reporting. Details of the questions are provided. | All | Aquatic | Farmers | |

| Phillips (2020) | Observation | Interviews | Anticipatory | 42 interviews | Some details are provided | Varroa | Bees | Beekeepers |

| Beyene et al. (2018) | Intervention Study | Contemporary | n/a | Analysis of the effectiveness of a smartphone disease recording system in Ethiopia | All | Cattle | farmers and vets | |

| Sawford et al. (2013) | Interviews | Retrospective | 10 | A list of questions/topic guide is provided. | All | Cattle | Vets | |

| Bronner et al. (2014) | Interviews | Retrospective | 20 interviews (12 farmers, 8 vets) | A topic guide is provided | Brucellosis | Cattle | Farmers and vets | |

| Bronner et al. (2015) | Secondary data analysis | Retrospective | n/a | The paper uses data from the surveillance system | Brucellosis | Cattle | Farmers and vets | |

| McFarland et al. (2020) | Interviews | Focus groups | Retrospective | 5 | Interviews used the Biographical Narrative Method | All | Cattle | Farmers |

| Hernández-Jover et al. (2016) | Interviews | Survey | Anticipatory | 182 surveys, 34 interviews | Interview topic guide is provided. Survey variables are provided. | All | Cattle | Farmers |

| Delgado et al. (2014) | Survey | Use of scenarios | Anticipatory | 524 | Scenario-based survey, drawing on Theory of Planned Behaviour. Survey questions are provided. | FMD | Cattle | Farmers |

| Delgado et al. (2012) | Workshop | Interviews, use of scenarios | Anticipatory | 40 interviews, unspecified number in workshops | Aim is to develop a survey instrument using qualitative methods. Survey is based on scenarios which are provided. | FMD | Cattle | Farmers |

| Hammond et al. (2016) | Survey | Anticipatory | 101 | Survey variables not provided | All | Crops | Farmers and advisors | |

| Hammond et al. (2016) | Survey | Anticipatory | 84 (28% response rate from 300) | Survey variables are provided. | All | Crops | Farmers and advisors | |

| Struchen et al. (2016) | Intervention Study | Interviews, survey | Contemporary | 6 | Research examines the use of a reporting intervention – a mobile reporting device. Survey variables are not provided. | All | Equine | vets |

| Robinson et al. (2012) | Focus groups | Retrospective | 12 | No detail on the form of the focus groups is given. | All | Livestock | Vets | |

| Robinson and Epperson (2013) | Focus groups | Retrospective | 11 | Focus Group questions are provided | All | Livestock | Vets | |

| Garza et al. (2020) | Interviews | Contemporary | 24 | Interview schedule is not provided. | All | Livestock | Vets/policy | |

| Sawford et al. (2012) | Interviews | Retrospective | 40 | A list of questions/topic guide is provided. | All | Livestock | Vets | |

| Gilbert et al. (2014) | Survey | Contemporary | 69 | Surveys are used to calculate the statistical probability of reporting samples to a laboratory. Survey is provided. | All | Livestock | Farmers | |

| Hernández-Jover et al. (2019) | Survey | Retrospective | 1140 | Survey variables are provided. | All | Livestock | Smallholders | |

| Wright et al. (2018) | Survey | Anticipatory | 200 | Survey based on Theory of Reasoned Action. Survey variables are provided. | All | Livestock | Farmers | |

| Hamilton-Webb et al. (2016) | Interviews | Focus groups, use of scenarios | Retrospective | 82 interviews, 9 focus groups (8-12 in each) | Scenarios are provided, broad topics are provided for the interviews | All | Livestock | Farmers and vets |

| Limon et al. (2014) | Interviews | Focus groups, survey | Retrospective | 240 | Topic list for the interviews is provided. | All | Livestock | Farmers |

| Guinat et al. (2016) | Survey | Retrospective | 109 | Survey variables are provided. | African swine fever | Pigs | Farmers | |

| Randrianantoandro et al. (2018) | Survey | Contemporary | 201 | Contingent valuation | African swine fever | Pigs | Farmers | |

| Elbers et al. (2010) | Interviews | Focus groups, survey | Retrospective | 15 focus group participants, 17 interviews, 409 survey responses | Survey questions are provided. No details on interview or focus group questions. | Classical swine fever | Pigs | Farmers |

| Zhang et al. (2016) | Observational data | Survey | Contemporary | 405 surveys | Survey provides background demographic data. Uses data from a longitudinal insurance/compensation scheme | All | Pigs | Farmers |

| Rao and Zhang (2020) | Survey | Observational data | Contemporary | 135 longitudinal survey participants | Survey provides background demographic data. Uses data from a longitudinal insurance/compensation scheme | All | Pigs | Farmers |

| Pham et al. (2017) | Survey | Use of scenarios | Anticipatory | 196 | Statistical analysis of responses to determine farmers reporting behaviours, using scenarios in a discrete choice experiment. Scenarios are detailed in the paper | All | Pigs | Farmers |

| Burns et al. (2013) | Interviews | Retrospective | 18 | Interview questions are provided | Avian influenza | Poultry | Smallholders | |

| Pramuwidyatama et al. (2020) | Survey | Anticipatory | 203 | Based on theory of planned behaviour. Some questions provided. | Avian influenza | Poultry | Farmers | |

| Elbers et al. (2010) | Interviews | Focus groups, survey | Retrospective | 33 farmers & 334 vet survey responses, 9 interviews, 14 participants in 4 focus groups | Survey questions are provided. No details on interview or focus group questions. | Avian Influenza | Poultry | Farmers |

| Pfeiffer (2018) | Focus groups | Use of scenarios | Anticipatory | 33 (3xfocus groups) | Focus groups used scenarios for discussion which are provided | All | Sheep | Farmers |

| Kuchler and Hamm (2000) | Observational data | Contemporary | n/a | Uses data from a longitudinal insurance/compensation scheme | Scrapie | Sheep | Farmers | |

| Palmer, Fozdar, et al. (2009) | Interviews | Retrospective | 37 interviews, 455 surveys | Interviews, topic guide used but not provided | All | Sheep and Cattle | Farmers | |

| Palmer, Sully, et al. (2009) | Survey | Retrospective | 37 interviews, 455 surveys | Survey variables are provided. | All | Sheep and Cattle | Farmers | |

| Hall et al. (2017) | Intervention study | Interviews, focus group | Contemporary | 16 interviews | Analysis of citizen science initiatives | All | Trees | All |

| Porth et al. (2015) | Interviews | Retrospective | 11 | No topic guide. Interviews trace actors in the outbreak. | ALB | Trees | All | |

| Crow et al. (2020) | Intervention study | Interviews | Contemporary | 900/500 survey responses | Analysis of citizen science initiatives | All | Trees | All |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.