Bilateral Spondylolysis of Lumbar Vertebra Secondary to Long Spinal Fusion for Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Case Report and Review of Literature

Yue Huang and Yulei Dong contributed equally to this article.

Grant sources: This research was supported by National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-120), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2507700), National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-D-004).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abstract

Background

Lumbar spondylolysis is a common cause of low back pain in adolescents. A lot of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with concomitant spondylolysis has been reported before, but only two cases with acquired spondylolysis following long fusion for scoliosis were reported. We described another similar rare case and discussed its causes and treatment options in this paper.

Case Presentation

A 17-year-old female underwent growing rod implantation, growing rod extension, and final long spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Then, she suffered from low back pain with a VAS of 1-2 points and gradually aggravated to a VAS of 7-8 points at 3.5 years after the final fusion. The X-ray images showed that there was L4-S1 instability. And the CT scan images showed new bilateral spondylolysis of L5.

Conclusions

These findings suggested that distal mechanical stress might cause spondylolysis of the distal vertebra following long fusion for scoliosis. Surgeons should keep instrumentation as short as possible and avoid choosing a low lumbar as LIV when they decide on the fusion levels.

Introduction

Spondylolysis is defined as a defect in the pars interarticularis, the narrow portion of the vertebral bone between the superior and inferior articular facets of the vertebral arch.1 It typically occurs bilaterally at L5 and L4.2, 3 Bilateral spondylolysis may cause forward displacement (slipping) of the vertebra relative to the next caudal vertebral segment, which is termed isthmic spondylolisthesis.4 These conditions are common causes of low back pain in adolescents.5 The prevalence of spondylolysis is 4.4%–4.7% in the general pediatric and adolescent population.6 It varies based on sex, age, activity level, and ethnicity.7 The prevalence can reach as high as 50% in Canadian Inuits, and 47% in child or adolescent athletes with back pain.8, 9 The exact cause of spondylolysis is still unknown, some evidence for “congenital theory” or “developmental theory” have been found.1 A significant number of cases of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with concomitant spondylolysis have been previously reported, with a prevalence of 7%.10 However, only two cases with acquired spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis following long fusion for scoliosis have been reported before. In theory, patients should receive medical treatment when symptoms arise from spondylolysis. Conservative treatment (rest, physical therapies, and sports-specific exercise) can be pursued as the initial approach. If conservative treatment is unsuccessful after more than 6 months, direct pars repair or arthrodesis should be considered. Herein, we present a rare case of a patient with bilateral spondylolysis secondary to long spinal fusion for idiopathic scoliosis and discuss the causes and treatment options.

Case Presentation

Initial Presentation

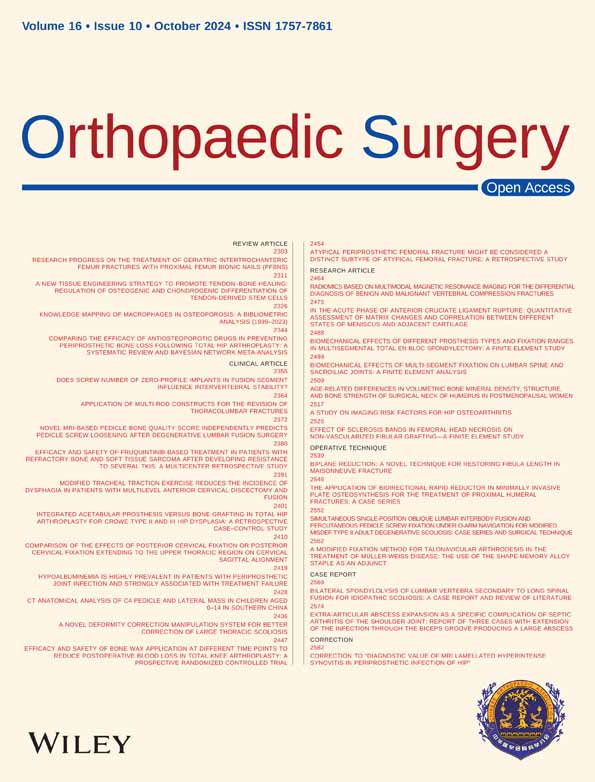

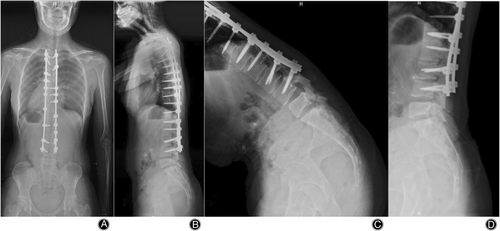

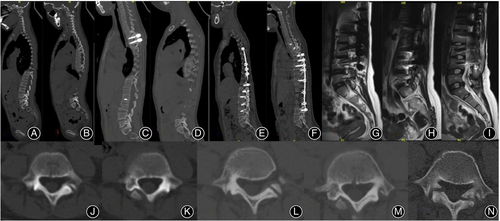

A 10-year-old female patient presented with scoliosis and uneven back upon her initial visit to our hospital. She did not exhibit any symptoms of low back pain, lower limb discomfort, or chest distress. All neurological examinations yielded negative results. According to her parents, scoliosis was sporadically detected through chest X-rays when she was 2 years old due to a pulmonary infection. Subsequently, she underwent 6 months of brace treatment. However, the thoracic curve and lumbar curve have recently worsened significantly to 40° and 43°, respectively (Figure 1A). There was no developmental abnormality of any spinal structure found by CT scan, including spondylolysis (Figure 4A,B). Thus, she was diagnosed with infantile idiopathic scoliosis.

Index Spinal Operations

The patient had recently begun menstruating, and the X-ray images revealed that her Risser sign was at stage I and her acetabular triangular cartilage was not fully closed. She had previously worn a brace for a period of time but was unable to tolerate it. Despite being 10 years old, the growing rod technique was chosen due to her height of only 135 cm and her high potential for spinal growth (Figure 1). The CT images before the surgery showed that the pars interarticularis of the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) were intact (Figure 4A, B, J, K).

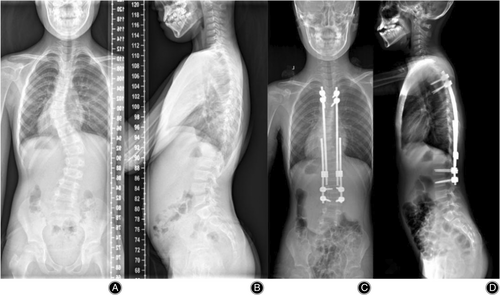

Subsequently, the patient underwent two additional growing rod extensions over the following 2 years. By age 13, her height had increased to 155 cm. X-rays indicated loosening of two proximal pedicle screws and the distal “adding-on” phenomenon (Figure 2A). She refused to wear a brace after we first found the adding-on phenomenon. There was still no significant spondylolysis by then (Figure 4C, D, L, M). Considering her Risser sign had been stage III, we performed the final spinal fusion from T3 to L4 (Figure 2C, D). There were coronal and sagittal disequilibrium immediately after surgery because of back pain.

Follow-Up

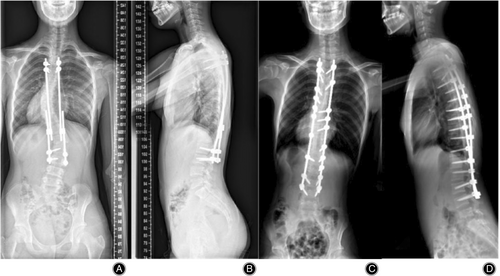

She recovered quickly from the operation, but still experienced occasional low back pain with a VAS score of 1-2 points. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, follow-up X-ray images for the next 3 years are not available. Two years later, the patient's symptoms of low back pain began to worsen, and the VAS score was increased to 4 points, which could be relieved after rest. Three and a half years after the final fusion, the patient visited our hospital again for her low back pain with a VAS score of 7~8 points. The X-ray images showed that her coronal disequilibrium had recovered, and her sagittal disequilibrium had gotten better, compared with immediately after final fusion (Figure 3A&B). Otherwise, the differences of L4-5 and L5-S1 Cobb's angles in the forward flexion and the backward extension X-ray images are 15° and 25 °, indicating that there is L4-S1 significant lumbar instability (Figure 3C, D). The CT scans and MRI also showed new bilateral L5 spondylolysis (Figure 4E, F, G, H, N). We recommend that she undergo internal fixation removal and direct pars repair; however, both she and her parents refused the surgery. Over the next 6 months, she occasionally experienced pain in both lateral-posterior thighs and numbness in the back of both feet. MRI images showed that her L5/S1 disc became degenerative (Figure 4I). She still refused surgical interventions. We advised rest, avoidance of strenuous activities, and appropriate exercise for her back muscles. At a 3-month telephone follow-up, she reported improvement in pain symptoms with a maximum VAS score of 3 points. The patient is currently under continued follow-up care.

Discussion

Recently, an increasing number of children and adolescents have been experiencing low back pain.11 Lumbar spondylolysis is a leading cause of low back pain, with a prevalence of 4.4–4.7% in the pediatric and adolescent populations.5, 6 It has been found that about one-third of these young patients will go on to develop some degree of spondylolisthesis, and 20% of them will become symptomatic.7, 12 .

The exact causes of spondylolysis are still unknown, possibly including both congenital and developmental causes.13 The incidences of spondylolysis in first-degree relatives of children patients and Canadian Inuits have significantly increased.14, 15 This evidence suggests that spondylolysis has a certain genetic predisposition. Three vertebral ossification centers, two lateral centers in the neural arch and a median center in the centrum, are formed at the third fetal month.16, 17 The development process can serve as the anatomical basis of spondylolysis, which may explain part of congenital lumbar spondylolysis. However, it was also disproved by the findings of no spondylolysis in infants or pre-ambulatory children.1

According to the “developmental theory,” spondylolysis is considered to be caused by repetitive mechanical stress to the pars interarticularis, a congenitally weak portion of the vertebrae.18 This is because the ossification of neural arches is incomplete in the growing children.19 Repetitive motions and/or overuse (mechanical stress) may cause fracture of the pars interarticularis, that is why young athletes have a higher prevalence of spondylolysis (23%~63%).2, 19, 20 Otherwise, the pars interarticularis of the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) will mechanically absorb more force of weight in the normal lumbosacral alignment and the lumbar lordosis of the spine.1 Thus, L5 is the most common level of lumbar spondylolysis.21

The previous two CT scans didn't reveal L5 bilateral spondylolysis in this patient. It means that her spondylolysis is not congenital. Considering the instability of L4-S1, there is overuse between L4 and S1 after long spinal fusion (T3-L4) for idiopathic scoliosis. Her postoperative sagittal imbalance might mechanically aggravate the distal lumbar instability. Repetitive mechanical stress causes the fracture of the L5 pars interarticularis. Two similar cases with new lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis after spinal fusion for scoliosis have also been reported before.22, 23 These three cases provide evidence for the “developmental theory” of spondylolysis. All their lowest instrumented vertebra (LIV) were L4. Lower LIV selection may bring on fewer distal mobile segments, increasing the mechanical stress on distal unfused segments. It has been confirmed to increase the risk of distal adjacent segment degeneration and other distal junctional problems dramatically, if LIV is lower than L3.24, 25 These patients often present with distal disc degeneration, low back pain, and a delay in the return to daily activities.10 Therefore, scoliosis surgeons should deliberately choose to fuse lower than L3 when they decide on the fusion levels.

For the treatment of spondylolysis, if there are no clinical symptoms, there is no need for treatment.6 Conservative treatments, including rest, physical therapies, sports-specific exercises, and/or bracing, are recommended for early-detected painful spondylolysis to reduce pain and restore bony union.6, 26 If the conservative treatment of more than 6 months is unsuccessful, direct pars repair or arthrodesis should be suggested.27 If a spondylolytic vertebra has a small gap (≤2 mm) and healthy adjacent intervertebral discs without spondylolisthesis, direct pars repair should be suggested.6 Although this patient has a mild degenerative disc, we still suggest direct pars repair due to her age. Otherwise, we also suggest removing implants to reduce distal mechanical stress considering there is good fusion mass between T3-L4. The limitation is that this patient did not undergo surgery, and we cannot know the prognosis.

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (K6236). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

Yue Huang and Yulei Dong contributed equally to this paper. All authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Conceptualization, Hai Wang and Jianguo Zhang; Investigation, Yue Huang and Fuze Liu.; Writing—Original Draft, Yue Huang, and Yulei Dong; Writing—Review & Editing, Yue Huang and Hai Wang; Visualization, Yifei Li; Supervision, Jianguo Zhang; Project Administration, Hai Wang and Jianguo Zhang.