The Emigration Conundrum: EU Countries of Origin of Migrants Between Integration and Demarcation

Abstract

Based on an analysis of parliamentary debates and party manifestos from 2000 to 2022 in three EU countries of emigration, this article responds to the following question: How emigration is discussed in the political discourse, by whom and why? The research on Poland, Portugal and Romania reveals that parties of the left and right address the societal impacts of emigration whilst simultaneously acknowledging the appreciation of citizens of EU freedoms. Tackling this conundrum, parties call for domestic demarcation for an issue that is partially European. They advocate for state intervention to improve working and living conditions and express concern for the sustainability of the national community responding to demographic changes. The variation amongst the case countries is evident in the dominance of a rightist framing in Central and Eastern Europe, emphasizing state intervention and concerns for the nation, and a leftist framing in Southern Europe, advocating solely for state intervention into the economy. Differently structured party systems and strength of cleavages explain this variation.

Introduction

Emigration on a large scale from Southern and Eastern European countries has not only socio-demographic and economic but also political consequences for the countries of origin of EU migrants (Bruzelius, 2021; Kyriazi et al., 2023). Long-term international migration and intra-EU migration contribute to the loss and eventual decrease of population in constituencies. Historically, as Hirschmann (1978) famously pointed out, emigration can promote political change by empowering the remaining population and their political claims. However, the direction of political development motivated by emigration is largely context dependent and seems to promote change towards either liberal or authoritarian political forces (Kelemen, 2020; Moses, 2011). Based on these observations, our interest in the topic takes a similar perspective; it focuses on how emigration affects politics, but it shifts the unit of analysis. Instead of examining the impact of emigration on election outcomes or the direction of political change, the article explores how emigration is discussed in the political arena of sending countries, by whom and why. By examining political parties' varying stances on emigration within and across party systems of countries of origin in the EU, we build an empirical and theoretical foundation for the study of emigration as an issue of political conflict.

We find that political parties rarely link concerns over emigration to Eurosceptic positions. In general, few political parties criticize the EU and its policy for freedom of movement of persons (FMP) as it warrants the opportunity for individual citizens to benefit from migration (Lutz, 2020). However, individual attitudes in countries of emigration highlight a worry over the negative effects of ‘EU emigration’ (Kyriazi and Visconti, 2023). Also, the phenomenon was related to the rise of right-wing populism in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) (Krastev and Holmes, 2019) and to spill over on EU governance (Roos, 2023). Building on this, we make a twofold argument: First, at the backdrop of the literature on cleavages (Kriesi et al., 2008; Grande and Kriesi, 2012), we find that political parties appeal to emigration as a collective concern for domestic socio-economic conditions and/or the nation, emphasizing indirectly a demand for demarcation and protection from liberal EU market integration and globalization. Second, we observe variations in terms of the dominance of leftist or rightist discourse on the topic. To explain this variation, we show that cleavages structure this conflict in country-specific ways (Manow et al., 2018). Structurally, in CEE, the politically dominant right links socio-economic and cultural issues, such as concerns with population loss and national survival, to emigration. This is analogous to how the political right in Western Europe connects immigration to issues of national identity and ethnicity (Kitschelt, 1997; Grande et al., 2019). By contrast, in Southern Europe, the left is the dominant political force and mobilizes for state intervention against low wages and substandard working conditions. On a theoretical level, the call for demarcation in CEE and Southern Europe means that parties of the left and the right linked emigration not only to domestic conditions and their critique but also to the asymmetrical development in the common market. Thus, we identify a conundrum: Policy solutions addressing emigration are sought domestically and framed predominantly as a socio-economic rather than a cultural issue. At the same time, the issue is partially European in terms of the policy of FMP and the dynamic of the common market that, to some extent, builds on the labour supply from the economic periphery. The emigration conundrum highlights that domestic conditions for EU integration have become both more salient and more important in mitigating the negative externalities of market integration whilst political solutions at EU level are limited.

For this study, we collected data using a comparative design in three EU case countries: Poland, Portugal and Romania. In these countries, we investigated the political conflict on emigration that was triggered by waves of large-scale emigration experienced either in the 2000s or in the 2010s against the background of EU membership and/or the financial crisis. The data comprise an analysis of parliamentary debates and party manifestos for election campaigns between 1999/2000 and 2022. Overwhelmingly, emigration from the case countries is facilitated by FMP. In 2022, 10% of Portuguese, 1.0 million citizens, resided in another EU country. The account is similar for Poland and Romania where 4% and 16% of citizens, 1.5 million Polish and 3.1 million Romanian citizens, resided long term in Western or Northern European countries (Eurostat, 2023, 2024a). Since 2009, more nationals left Poland (−935,000), Portugal (−170,000) and Romania (−699,000) than returned or immigrated (Eurostat, 2024b, 2024c). The country of residence for EU emigrants is much more likely to be another EU than a non-EU country (Eurostat, 2024d). Therefore, we identify EU emigration as the long-term movement of citizens from the three case countries that largely takes place within the scope of FMP. Whilst political discourse does not always neatly separate between general emigration and emigration towards other EU countries, references to the ‘West’ and the ‘European Union’ indicate that politicians refer to the most recent and predominantly European emigration.

This article is structured as follows: The next section reviews the literature on cleavages and party systems to formulate expectations on how emigration might be framed differently by political parties in countries of origin. This is followed by Section II, an overview of the empirical data and the methods used for analysis. Section III presents the empirical analysis. We conclude the article with a discussion of the results.

I Emigration and Political Conflict

Emigration, like immigration, is linked to the processes of globalization and EU integration (Kyriazi and Visconti, 2023). Considering this, our research adopts the heuristic on changing cleavages in Western Europe's political arenas suggested by Grande and Kriesi (2012, p. 22), which encompasses struggles related to both processes. On the socio-economic axis, the model incorporates conflicts arising from globalization, framing them in terms of demands for state intervention versus further liberalization. On the cultural axis, it includes conflicts between cosmopolitan and national orientations. These cleavages determine political coalitions that cross-cut traditional left–right distinctions on economy and culture in terms of how they politically represent the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ of globalization and political transition (Kriesi et al., 2008, p. 4; Sałek and Sztajdel, 2019, p. 202). The socio-economic and cultural preferences of the winners are merged in a demand for ‘integration’, meaning openness for cosmopolitan norms and economic liberalization. Conversely, the losers demand ‘demarcation’, seeking the protection of the economy from competition through state intervention and adherence to the national community (Kriesi et al., 2008, p. 9). We applied this heuristic, originally developed for Western Europe, to Southern European and CEE countries because political systems there have been going through transformations from authoritarian rule to liberal democracy and a market economy. The caveat in translating the heuristic to CEE and Southern Europe is that the strength of cleavages and their representation in party systems have been largely path dependent (Kriesi et al., 2008, p. 10; Manow et al., 2018). In Southern and Eastern Europe, we find that party systems are still developing, which represent weak (meaning less institutionalized) and changing cleavages. (Jaskiernia, 2017, p. 236; Manow et al., 2018). Thus, developing party systems may give a less stable representation of societal conflicts compared to Western Europe. Still, we observed that cleavages and the various party-political representations in Southern Europe and CEE countries largely explained the dominance of a leftist or rightist framing of emigration in the political discourse. Additionally, factors such as electoral opportunities and a party's role in government or opposition influenced the intensity of that party's positioning on an issue (Grande and Hutter, 2016, pp. 28–29). The cleavage heuristic is useful for understanding how parties position on emigration in terms of frames. By ‘frames’, we mean interpretive schemes and value judgements that offer problem identifications and solutions (Entman, 1991, p. 553). Frames select and give weight to certain aspects of reality. For political parties, framing is a strategic tool because it mobilizes voters to think about party policies along particular lines (Jacoby, 2000).

To substantiate the argument that political conflict over emigration is primarily expressed as a demand for demarcation, we first analyse how the literature links emigration to cleavages and then explore how left- or right-wing parties may frame the issue within their ideological perspectives according to the integration-versus-demarcation model. Second, we review the party systems and country-specific cleavages in the countries of our sample to explain variations in left- or right-wing parties' positioning on emigration.

Explaining the Framing of Emigration Along Cleavages

Like immigration, emigration can spur political conflicts that intersect with welfare state and labour market issues (the socio-economic cleavage) or concerns about national security and ethnic identity (the cultural cleavage). Mobilizing on emigration highlights governmental and state shortcomings in fostering the conditions for societal well-being (Moses, 2011; Roos et al., 2024). This connects emigration to the socio-economic cleavage by highlighting adverse working and living conditions specific to each country, which drive outward migration. On this cleavage, Dancygier et al. (2022, pp. 5–6) find that a decline in life quality in depopulating regions generates frustration for those who remain. Such grievances can be mobilized by the populist right against incumbent political parties. However, the populist right has not only been observed mobilizing on emigration regarding the factors that motivate people to leave a country. In her study of mass emigration from Spain during the economic crisis, López-Sala (2019, p. 273) found that the exodus prompted claims by a populist left-wing party for the emigrated nationals' ‘right to return’. This focus on inequality and a demand for state intervention in the market, both by the left and by the populist right, can be either domestic or European in scope and can include criticism on structural imbalances in the EU's single market (Finnsdottir, 2019; López-Sala, 2019). The socio-economic axis can also include positions on emigration that highlight the benefits generated by the flow of remittances from nationals abroad into state budgets and additional household income. The transfer and productive investment of these remittances can be viewed within a framework that highlights the mutual benefits for individuals and their countries of origin, rather than viewing emigration as having a zero-sum outcome (Lee, 2017). Following the heuristic of Grande and Kriesi (2012, p. 22), and in contrast to the interventionist position described before, this position is integrationist, emphasizing the benefits of open markets and economic liberalism.

On the cultural axis of political conflict, liberal and leftist demands for a cosmopolitan agenda marked by the promotion of individual rights and EU integration contrast with the right's calls for demarcation, characterized by a focus on religious values, communitarianism and, at times, even nationalism (Kriesi et al., 2008). On the latter issue, Krastev and Holmes (2019, pp. 38–39) relate demographic decline in the CEE region to rising public and political concerns about ‘national extinction’ due to emigration, driving fears of ‘ethnic disappearance’ that political parties can leverage to support an ethno-nationalist agenda. In this vein, Finsdottir (2019, p. 10) notes that in CEE countries, an emphasis on ethnic understanding of national identity has emerged in reaction to EU integration, where traditional ties between territory and people are increasingly disconnected by EU citizenship and FMP. Indeed, emigration has become a salient issue in countries of emigration, with societal concerns about its social effects potentially leading to critiques of the EU and FMP (Kyriazi and Visconti, 2023). Political parties, however, must approach such explicit critiques with caution, as citizens appreciate the mobility rights granted by EU membership (Lutz, 2020, p. 5). Support for FMP is highest in poorer EU countries, which are often also countries of emigration (Vasilopoulou and Talving, 2019, pp. 813–816). Interestingly, whilst EU scepticism exists in these countries of the South and East, it is not typically connected to FMP (Vasilopoulou and Talving, 2019, p. 817). Consequently, the political right in emigration countries must address voter concerns for emigration without criticizing FMP. In contrast, market liberal parties on the centre and right can easily emphasize the opportunities that come with FMP (Hadj Abdou et al., 2022, p. 332). Similar positions can be expected from culturally liberal and left parties, focusing on the cosmopolitan values of openness and exchange that support a transnational European project (Grande and Kriesi, 2012, pp. 21–22).

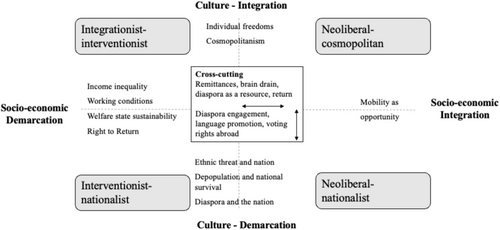

Debates on measures aiming at encouraging the return or continued engagement with nationals residing abroad can be located along the cultural and/or socio-economic axes, depending on the nature of the relationships they emphasize. Measures focusing on the diaspora as a part of the national (ethnic) community, sharing the idea of a cultural, ethnic or religious homeland, often reflect a cultural position aimed at demarcating the nation. Conversely, measures aimed at incentivizing return through financial or other means are primarily socio-economically motivated (Lafleur and Vintila, 2020). In terms of the demarcation–integration heuristic, addressing the diaspora in cultural and economic terms generally reflects a nationalist and interventionist position. Emigration and emigrant communities can also be framed within (post-)colonial understandings of the nation, where citizen mobility historically functioned as part of a territorial state expansion. This is the case in Portugal, where emigration continues a legacy of mobility (Baganha, 2003). Thus, addressing the diaspora can have dual implications: It can serve to demarcate the nation and its domestic economy, or, conversely, it can help expand the realm of the nation by integrating cosmopolitan values into national identity at home and abroad. Building on the heuristic of Grande and Kriesi (2012, p. 22), Figure 1 summarizes the frames of emigration along the cultural and socio-economic, integration and demarcation lines of political conflict.

Explaining Variation: Cleavages and Party Systems in Southern Europe and CEE

The countries in our sample share a history of transition from authoritarianism to liberal democracy and market economy. Whereas the legacy of communism in CEE countries has discredited the radical left (Jaskiernia, 2017; Ost, 2018), in Southern Europe, the lasting impact of national-conservative authoritarian rule has rather served to inhibit the radical right, as the example of Portugal and Spain shows (Da Silva and Mendes, 2019, p. 141). Within these path-dependent structures, there emerged different party systems that influence which cleavages can become politicized and by whom (Manow et al., 2018).

For the case of Portugal, Ferreira da Silva and Mendes observe a political landscape where parties compete on socio-economic rather than cultural issues. Here, the radical right is traditionally weak, with the centre-right represented by the Social Democratic Party (PSD) or the conservative Christian Democrats (CDS-PP). Along with the left-wing Socialist Party (PS), the PSD usually secures two thirds of the vote. The radical-right party CHEGA (Enough), which emerged in 2019 as an anti-establishment force, has until recently not achieved comparable success to other radical-right-wing parties in Europe, as socio-cultural issues remained marginal in Portuguese political discourse (Mendes and Dennison, 2020, p. 18). Overall, the EU has been a low-salience issue. Demarcation in Portugal, developed along the socio-economic axis, finds expression by some leftist parties calling for state intervention against market liberalism.

In CEE countries, cultural issues have come to eclipse the socio-economic dimension in structuring political conflict (Sałek and Sztajdel, 2019, p. 192). The post-communist left has largely faded in Eastern Europe as a whole, with conflicts on socio-economic issues shifting towards the cultural dimension (Ost, 2018). Social protectionism through state intervention and nationalism is often intertwined in CEE countries and is represented by parties of the right and left, including agrarian and populist parties. These parties are opposed by cultural and market liberals—that is, the cosmopolitans who tend to favour market capitalism and individual opportunity over class-based interests (Kitschelt, 1997; Sałek and Sztajdel, 2019). The emphasis on the cultural dimension and the downplaying of economic conflict is particularly prominent in Poland. The centre-right Law and Justice party (PiS) adopted a populist agenda and established a new national and social interventionist party variant. On cultural issues, it mainly competed with the liberal-centrist Civic Platform (PO). The cultural conflict in Poland is characterized by its religious–secular divide, the defence of Catholic values and both pro- and anti-nationalist and nativist agendas. Whilst PO is EU-friendly, PiS appeals to nationalist citizens who view the EU as a tool of Western domination (Ost, 2018, p. 120). In essence, demarcation in Poland is largely culturally framed and pits nationalists with a social agenda against liberal cosmopolitans.

Compared with Poland, the Romanian case is more complex. Except for the liberal party (PNL), there is little ideological stability within the Romanian party system or electorate – conflicts along the cleavages do not seem to be fully represented by the developing party system. The social democratic ‘left’ in Romania (PSD) tends to gravitate towards the right and represents the rural population, including its socio-cultural values – which could be considered conservative in comparison with those of the Western European left (Mișcoiu, 2022, p. 160). The centre and right parties hold economically liberal and culturally conservative views. In fact, the Union to Save Romania (USR) is the only party with genuinely liberal positions on both economic and cultural fronts (Mișcoiu, 2022, p. 161). Since 2016, cultural issues connected to nationalism have gained prominence in party politics. The rise in voter support for the openly nationalist and right-wing Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) during the 2020 parliamentary elections reflected the increasing importance of socio-cultural divides in Romania (Mișcoiu, 2022, p. 162). Despite the ascendance of the far right and the focus on cultural issues, EU scepticism has not resonated significantly with either the party system or electorate (Mișcoiu, 2022). In Romania, demarcation was mainly cultural and centred on nationalism but was not connected to EU scepticism.

Based on our discussion of possible left and right framings of emigration within the party systems, we assume that party systems in Southern Europe will position the left to mobilize on emigration. We expect a demand for demarcation there, with a focus on the socio-economic dimension. In CEE party systems, we expect the conservative right to mobilize on emigration through nationalist demarcation. However, it is unlikely that parties will link emigration with a critique of FMP or EU integration, as voters appreciate the opportunity of mobility given by EU membership.

II Methods and Data

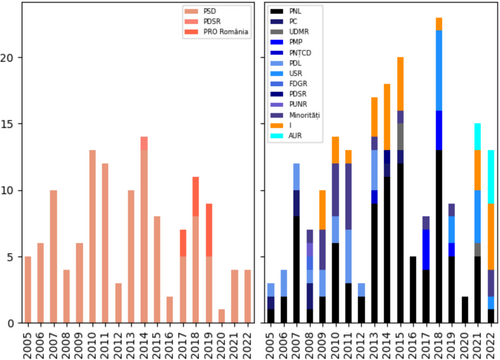

For our study, we utilized two sets of data for each case country. First, we conducted a quantitative analysis of parliamentary debates in the case countries from 2004/2005 until 2022 to assess the intensity of party positioning on emigration. We measured the number of statements by parliamentarians in which ‘emigration’ was mentioned and allocated them across parties from the left and right. To properly understand how political conflict on emigration is framed, we also carried out a quantitative and qualitative analysis of 111 party manifestos from all the relevant parties in our case countries (please see Appendix S1 for references of party manifestos and party acronyms). The data cover the period from 1999/2000 to 2020 for Poland and Romania and 2000–2022 for Portugal. This enabled us to cover a time span of sufficient duration to discern the main trends with respect to party positioning on emigration. Party manifestos were translated into English using Google Translate and DeepL. We analysed these documents based on a coding scheme that identifies different frames related to emigration (Figure 1). Our selection of codes covers the potential party positions along the left (interventionist) and right (neoliberal), socio-economic divide and culturally liberal (cosmopolitan) and communitarian (nationalist) axes of political conflict in European countries. Subsequently, we analysed the data using both the quantitative and qualitative content analysis tools in MAXQDA. This enabled us to quantitatively compare the frequency of certain codes, whilst qualifying their content by summarizing the statements of parties. We then categorized statements into left and right dimensions of cultural and socio-economic frames for emigration, identifying positions in favour of integration or demarcation.

III Emigration and Party Positions in Southern and Eastern Europe

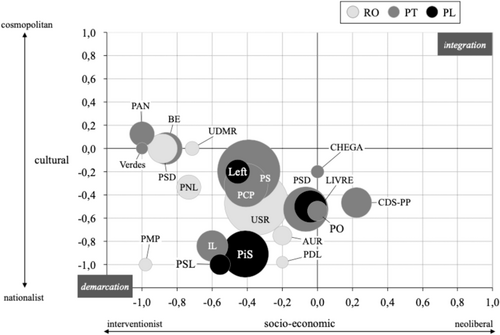

In Portugal, emigration was an issue for left-wing parties, predominantly from the opposition, who criticized the substantial emigration from the country sparked by the economic crisis and subsequent austerity measures. As indicated in Figure 2, PS and the communist party (PCP) primarily focused on the socio-economic axis linking anti-emigration measures to a call for state intervention. In Poland, emigration became a pivotal aspect of the PiS party's cultural agenda to ‘defend’ the sustainability of the Polish nation. Together with the Polish People's Party (PSL), an agrarian and conservative party, the predominating right framed emigration through the lens of social interventionism and nationalism, calling for demarcation. In our last case study, Romania, both the liberal USR and the right-wing AUR have also adopted stances towards emigration that focus on interventionism and nationalism. However, positions on the cultural axis calling for nationalist demarcation emerged only recently, coinciding with the AUR's rise during the 2019 parliamentary elections. Across the sample, the discussion of emigration was not linked to scepticism towards the EU or FMP.

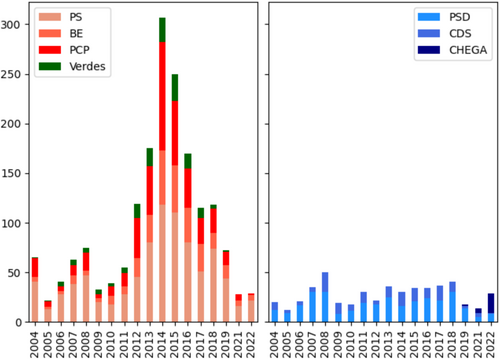

Emigration, Party Positions and Framing in Portugal

Measurement of the topic's political salience in parliamentary debates indicates that the left has placed greater emphasis on the issue (Figure 3). It mainly debated the issue on a socio-economic level, discussing migration flows in relation to economic prosperity and labour market conditions as drivers of emigration. Other issues of concern on the socio-economic axis pertain, first and foremost, to the role of the diaspora. This is viewed as vital to strengthening the country's economic development through remittances, returns or investments. When parties connect cultural issues with emigration, they also focus on the diaspora. Parties from both the far left (PCP) and the far right (CHEGA) have advocated for diaspora engagement, as well as its protection and representation.

The dominant socio-economic framing, criticizing conditions on the labour market in relation to emigration from the country, became salient when left-wing opposition parties politicized the issue for the 2015 election. Emigration rates had doubled from 65,000 in 2010 to 120,000 in 2013, spurred by the financial crisis and effects of the austerity policies that were adopted by the ruling PSD and CDS-PP coalition. Primarily, the left also continued to mobilize after the 2015 election, both in and out of government, on behalf of the state interventionist frame on emigration.

Growing emigration in the early 2010s was leveraged by the PS as evidence of a neoliberal economic policy failure, whilst the PSD primarily viewed emigration as an opportunity and safety valve against unemployment. Thus, PS policy proposals focused on the economic incentives required for Portuguese citizens to either stay or return (PS, 2015, p. 50, 2022, p. 35). The 2015 manifestos of leftist parties condemned the government's failure to protect citizens from the socio-economic fallout of the economic crisis. Amongst others, the PS and the PCP viewed the emigration of young and qualified citizens as ‘a process of forced emigration that expelled them from the country for economic reasons’ (PCP, 2015, p. 10), which would also lead to a sharp drop in the birth rate (PS, 2015, p. 78). The socialists identified these as causes for the degradation of ‘the medium and long-term sustainability conditions of the social security system’ (PS, 2015, p. 78; see also Verdes, 2015, p. 9). Even after the peak emigration years during the economic crisis, the left continued to emphasize the welfare state's important institutional role in retaining the population by cushioning insecurities and offering services to stabilize the birth rate and incentivize return (Left Bloc (BE), 2019, p. 7; PCP, 2015, p. 32, 2019, pp. 23, 79, 97; PS, 2019, pp. 130–133). Before the crisis, the left had addressed emigration as a socio-economic issue, focusing on the loss of human resources to the national economy (PS, 2002, pp. 103, 163, 2005, pp. 21, 76), on rural-to-urban migration (BE, 2009, p. 74) and as part of a broader critique of uneven capitalist development and inequality in Europe (BE, 2009, p. 74; PS, 2002, p. 163).

Differences between the left and right were particularly pronounced during the crisis years. The PSD, which governed in coalition with the CDS-PP from 2011 to 2015, aimed to sideline the issue of emigration in the run-up to the 2015 election. In the years before the economic downturn that started in 2010, the PSD framed emigration as positive to economic growth, focusing on the increasing inflow of remittances and the potential for establishing new businesses at home or abroad (PSD, 2005, p. 100, 2009, p. 29). After the crisis in the mid-2010s, the PSD shifted its focus away from emigration itself towards the positive impact of a large community of nationals living abroad. In their joint manifesto with the CDS-PP, they highlighted the diaspora's vital importance to ‘the development of tourism, the promotion of exports, culture and the image of Portugal in the host countries’ (Agora, 2015, p. 146) and stressed that Portuguese communities abroad, especially those in the second and third generations, should be seen as ‘strategic partners […] capable of contributing to the development of the national economy’ (Agora, 2015, p. 149). Next to PSD, the other centre-right party CDS-PP also focused on the diaspora as an economic resource, rather than seeking to mitigate emigration flows before, during and after the crisis (Agora, 2015, 2019; CDS-PP, 2005, p. 98). Emigration was framed by the right as an opportunity for the individual and the country, rather than a loss of brainpower and people. In comparison with the left, the PSD drew less attention to the social and economic push factors explaining emigration (PSD, 2019, p. 98, 2022, p. 41). The right had acknowledged some of the negative effects of emigration on rural areas in Portugal (CDS-PP, 2009, p. 18; PSD, 1999, p. 41, 2011, p. 56) and the issue of brain drain (CDS-PP, 2009, p. 206; PSD, 2011, p. 24); significantly, it did so before, rather than during, the crisis. The CDS-PP and PSD largely opted for a strategy of deflection, focusing on the diaspora as a resource and emigration as an opportunity (Agora, 2015). The centre-right and populist right-wing parties in Portugal rarely framed emigration as a threat to the nation or an ethnically defined community. CHEGA (2022, p. 4) mentioned the issue only once in relation to immigration, strictly opposing the replacement of emigrated Portuguese by immigrants. Indirectly, the party linked the issue of a declining Portuguese population to the issue of ethnicity by demanding a halt in the emigration of ‘compatriots’. CHEGA's unique stance in the Portuguese party spectrum highlights the limited representation of the far right.

In the Portuguese context, the link between emigration to nation and culture primarily stems from the country's large diaspora. About five million Portuguese and descendants of Portuguese emigrants live abroad, in other European countries or former colonies. Although its colonial era ended in the 1970s, migration into and out of the country is still viewed as part of the Portuguese colonial legacy and cosmopolitan understanding of Portugal as a nation of emigrants (Baganha, 2003). This legacy lives on in the country's continued political ties to its former colonies and the Lusophone world, as well as support for the Portuguese diaspora abroad. Therefore, the topic of emigration and the surrounding debate tended to focus on policies that engage with the diaspora to promote Portuguese culture and language abroad. Accordingly, both the centre-right (CDS-PP and PSD) and the liberal and left-wing parties (PS, Verdes, BE and PCP) cultivate stances that frame the diaspora as an economic resource and a significant cultural asset to the Portuguese nation domestically. Despite these commonalities, as the manifesto analysis in Figure 2 shows, emigration resonates more with the left than the right in Portugal's party-political spectrum. Core to the leftist position and largely overlooked by the right is a critique of the domestic living and working conditions that drive emigration. This framing of emigration calls for a state intervention and marks a demarcation against neoliberal economic policy.

Emigration, Party Positions and Framing in Poland

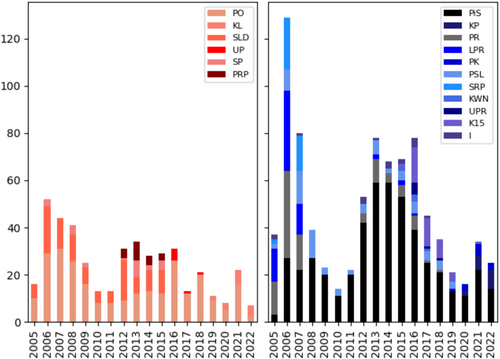

In Poland, centre and right-wing parties mobilized on the issue of emigration on the cultural and socio-economic dimensions. In comparison, the left remained marginal on this issue. On the conservative and right, the PiS gave increasing salience to the topic around the parliamentary election in 2015. Its main competitor, the liberal and centrist PO, also tackled the topic, but with less intensity (see Figure 4).

In their manifestos, all parties acknowledged the reasons for emigration, mainly criticizing the economic and social conditions in Poland such as low wages, unemployment, disappointing living conditions and a tough housing market (PiS, 2011, pp. 44–45, 2015, p. 13; PO, 2007, p. 37; PSL, 2015, p. 13). They highlighted issues such as youth emigration (PiS, 2015, p. 112; PSL, 2011, p. 5) and pointed to depopulation, shortages on the labour market and adverse impacts on the welfare state (Left, 2011, p. 212; PiS, 2015, p. 107; PO, 2019, p. 58).

For the PiS, emigration has become pivotal to its understanding of Poland as a nation and the Poles as an ethnic community. It framed the outflow of citizens not only in socio-economic terms but also as a threat for the nation's future: ‘Among all the challenges facing Poland in the next decade, the most important one is to avoid the collapse of civilization caused by the depopulation of our country’ (PiS, 2015, p. 107). Depopulation is linked to the ‘mass emigration of Poles’ and a ‘dramatically decreasing fertility rate’ (PiS, 2015). Notably, the party's understanding of what promoted emigration combined socio-economic factors with a nationalist frame, as its 2007 manifesto reflects: ‘It has been forgotten that the Polish Nation also includes Poles […] whose financial situation forced them to leave their homeland in search for work’ (PiS, 2007, p. 54). Labour migration of Poles is framed negatively, as a loss for Poland. The PiS successfully linked the ills of the Polish economy and welfare state challenges to the liberalization undertaken during the PO's liberal and centrist government (2007–2014). Then Prime Minister Donald Tusk was accused of ‘liberal illusions’ in promoting privatization and liberalization of the Polish economy and the public sector, allegedly leading to the forced emigration of Poles, demographic collapse and indebtedness (PiS, 2015, p. 74). Elected to government in 2015, the party re-focused the country's growth model by increasing salaries, raising the minimum wage as a means of countering emigration: ‘The Polish economy cannot only compete with low wages, as was the case in the past, because the consequence of such a policy was mass economic emigration of Poles. On the other hand, all Poles should benefit from economic development, regardless of their profession, place of residence and social affiliation’ (PiS, 2019, p. 210).

Another key issue for the PiS was its drive to acknowledge the value of the Polish diaspora and maintaining relations with it. The 2015 and 2019 manifestos increasingly emphasized the rights of Poles abroad, their political representation and their cultural ties to Poland: ‘Poland will take care of our compatriots living abroad, in the East and the West. Maintaining Polish statehood, building its strength and the sense of community of Poles will be our joint work’ (PiS, 2015, p. 159, 2019, p. 223). The party characterized Poles living abroad as part of the national community and as instrumental in ‘strengthening national identity’, ‘cultivating historical memory’ and serving as ‘ambassadors’ of Polish interests on the international arena (PiS, 2019, p. 223). In contrast to Portugal, where parties primarily viewed the diaspora as an economic resource, PiS underscored its communitarian and nationalist approach towards the diaspora by calling for the promotion of Polish language and traditions in schools and public spaces abroad, as well as the goal to incentivize return (PiS, 2015, pp. 159–160, 2019, pp. 175, 186).

When framing emigration, PiS combined a nationalist stance on emigration and the diaspora with state interventionist claims. It called for better living and working conditions and criticized a lack of social policies providing for housing, general family support and health care for Poles in Poland. The party identified these issues in opposition and government (PiS, 2011, p. 45, 2015, pp. 13, 112, 2019, p. 68), differing in this regard from its main competitor, the liberal and centrist PO. The latter also tried to politicize the topic of emigration – but only from the socio-economic angle. It almost exclusively framed the issues surrounding emigration in terms of brain drain and labour shortages, casting these as a problem of the medical sector (PO, 2007, p. 37). All in all, the PO lacked a clear position on the issue. Early in the 2000s, the party had even encouraged emigration as a labour market strategy, promoting education and foreign language skills as ways to prepare for employment abroad (PO, 2001, p. 26, 2005, p. 23). In contrast to the PiS, the PO (2015, p.23) focused on incentivizing return, offering scholarships to university students of Polish origin and training for entrepreneurs who relocated to Poland. ‘[T]heir education, energy and diligence should find an outlet in working for Poland’, it stressed. ‘They must not be discouraged from making a decision to return to their homeland’ (PO, 2007, p. 79). Interestingly, when PO was part of an alliance with liberal and left parties for the 2019 elections, it hardly mentioned the issue anymore. It merely stated that ‘Poland must cease to be a “factory” of specialists for other countries’, focusing on brain drain from the medical sector (PO, 2019, p. 56). PO included some statements on the promotion of closer relations with the diaspora, also emphasizing protection of their rights and freedoms (PO, 2007, p. 81, 2011, p. 38), framing this issue in a more culturally liberal and cosmopolitan way. PSL, the agrarian party, which joined a coalition government with PO (2007–2014), framed emigration in a way like the PiS (PSL, 2007, p. 3, 2011, p. 5, 2015, p. 23). Other parties of the left, in particular the Democratic Left Alliance or the Leftist and Democrats, both of which were dissolved during the 2010s, struggled to adopt a coherent position on emigration. After 2007, these parties dropped their core leftist critique of emigration with its focus on living and working conditions in Poland. Instead, they aimed for more immigration and intensified efforts to encourage return as innovation measures (Left, 2011, p. 202).

In Poland, therefore, the PiS stands out as the party monopolizing the issue of emigration for voter mobilization. More than other parties of the right, centre or left, the PiS has consistently taken a stance on emigration, framing the topic by combining the socio-economic issues related to emigration with cultural frames that highlight it as a threat to the Polish community and nation. The party's approach stressed demarcation against the consequences of liberalization, by adopting an interventionist position and a nationalist position.

Emigration, Party Positioning and Framing in Romania

Despite high emigration rates, the salience of emigration remained low in Romania except during the 2020 parliamentary elections (Figure 5). During the 2000s, the liberal-right PSD, the country's largest party, mentioned emigration but failed to develop the issue to the extent that other parties did. Only since 2020 have opposition parties, a liberal party (USR) and a right-wing party (AUR), both with voter bases in the diaspora, increasingly mobilized around emigration in terms of the socio-economic and cultural axes. This pattern may develop along the same lines as those observed in Poland.

In the 2020 parliamentary elections, the liberal USR and the extreme-right AUR stood out for their emphasis on emigration, although other parties such as the liberal-right PNL and the right, national-conservative PMP also mobilized more intensively around the issue than in past elections. Thus, conservative parties have become more engaged with the issue of emigration (see Figure 5). In terms of the frames utilized by parties, analysis of the 2020 manifestos shows emigration predominantly framed as a major socio-economic challenge for Romania. Parties put different emphasis on reasons for emigration, highlighting the shortcomings of the Romanian state and society or the unequal structures of a European labour market that creates a pull factor for Romanian workers. Because of these emigration effects, the parties identify brain drain, depopulation and economic decline, labour market shortages, challenges to the welfare state and remittances (AUR, 2020, p. 16; PMP, 2016; PNL, 2020; USR, 2020, pp. 169, 237). The EU was not criticized in relation to emigration. Whilst the manifestos covered several aspects of emigration, including its socio-economic and cultural dimensions, the conservative and right-wing parties made greater use of nationalist frames. A comparison between the manifestos of the AUR and USR sheds light on these differences. AUR identified emigrants as part of ‘the body of the Romanian nation’ and as a ‘loss for Romania’ (AUR, 2020, p. 2), linking emigration to demographic decline, framing it as a threat to the Romanian nation and stressing traditional Christian family values and expanded family benefits as solutions (AUR, 2020, p. 17). Without focusing on Christianity and family values, the USR also aimed to tackle emigration by reforming the welfare state and increasing child allowances. Whilst the USR proposed labour market interventions to address low wages and living conditions, the AUR favoured a liberal market approach, criticizing state interventions as ineffective – a stance common amongst right-wing parties in CEE that have not yet developed a strong position on state interventionism like the PiS in Poland (Sałek and Sztajdel, 2019, p. 206). The AUR not only called for better social services in terms of health care and education but also stressed corruption and the business environment as factors driving emigration (AUR, 2020, p. 21). Other right-wing parties, the Democratic Liberal Party (PDL) and the PMP, made similar claims about the quality of social services in relation to emigration and the need to create a better business environment that would reduce outward migration amongst the young (PDL, 2008; PMP, 2016, p. 6). Consistent with its agenda on welfare state reform, the USR was most elaborate in discussing the sustainability of social security. Its manifesto identified raising the minimum wage, offering competitive salaries and focusing on working conditions in education and health as measures that could mitigate the loss of people (USR, 2020, p. 45). Even before emigration gained salience during the 2020 elections, the USR emphasized the position of Romania as a ‘developing country’ and its competitive disadvantages in the European labour market (USR, 2016, p. 12). Despite this analysis, the party took an affirmative position on FMP within the EU and encouraged the mobility of Romanian workers and companies (USR, 2020, p. 370).

The position on the diaspora once more emphasized crucial differences in approaches towards emigration. AUR pursued a communitarian and nationalist approach and sought to strengthen feelings of national belonging of Romanians abroad by promoting the Christian faith, Romanian traditions and language. Interestingly, the AUR reinforced the national identity of the Romanian diaspora by emphasizing the temporary nature of Romanian mobility and Romanians' rights as EU citizens, rather than their long-term migration: ‘The Romanians who settled in the last two decades in the European Union are not immigrants. They are citizens of the European Union acting on the basis of the rights they have’. (AUR, 2020, p. 8). This is not a contradiction, but rather a strategy through which the party sought to engage the national identity of Romanians abroad whilst promoting their EU citizenship. The AUR draws its voter base mainly from the diaspora. Whilst these constituents benefit from FMP, they are disadvantaged by substandard working conditions in Northern and Western Europe (Arnholtz and Leschke, 2023). On its website, the party positions itself as a diaspora advocate, linking people's grievances to emigration issues: ‘Are you tired of seeing how Romanians are forced to look for work in other countries? Are you tired of seeing how everything we value about our country and our people is being trampled on?’ (AUR, 2022).

The USR also stressed cultural issues in maintaining a strong link to the diaspora and the importance of political rights and diplomatic protection abroad, whilst placing equal emphasis on Romanians abroad as an economic resource. ‘The Diaspora can no longer be a side chapter’, it stated, ‘the Diaspora contributes more than 3 billion Euro a year to the country's economy and has huge human and financial potential for its future’. (USR, 2020, p. 401). In contrast to the AUR, which saw the value of circular migration, USR was keen to increase the return of Romanians and suggested concrete measures to that end, including financial incentives for returnees and domestic reforms in the areas of social security and education (USR, 2020, p. 406). Whilst recognizing the individual nature of the decision to return (USR, 2020, pp. 85, 402), the party also sought to promote a national Romanian identity amongst the diaspora (USR, 2020, p. 402). With strong support from Romanians abroad – similar to the AUR – the party's manifesto strongly featured cultural offers, improved consular services and political representation (USR, 2020, pp. 403–404). Reflecting their voter bases, the manifestos target different groups of people, including skilled Romanians (USR) and all Romanians abroad (AUR), when mentioning the issue of emigration. This party positioning pattern and framing of emigration in Romania echo that of Poland and the position of the PiS; however, the AUR and USR do not represent majorities in the way that Poland's PO and PiS parties do. Concerning emigration framing, they offered a complementary approach: The AUR adopted a communitarian nationalist approach towards the diaspora on the cultural axis, whilst the USR focused on state interventionism in the socio-economic dimension. Together, these two parties advocated for an interventionist position and a nationalist position that called for cultural and economic demarcation.

Conclusion

Our research into the dynamics of party positioning and framing of emigration in Portugal, Poland and Romania offers valuable empirical and theoretical insights. Empirically, the data show variation in party positioning across the sample countries. Analysis of how frequently the topic arose in parliamentary debates and a study of party manifestos confirm that in Portugal, left-wing parties emphasized emigration, whilst in Poland, it has become a more politicized topic amongst the conservative right. Romania also tilts towards more conservative and right-wing views when discussing emigration, although in our study, the most elaborate agenda on the issue was presented by USR, a centrist and liberal party. We attribute the prevalence of left- or right-wing party positioning on emigration in Portugal and Poland, respectively, to the country-specific cleavages on which these parties build their platforms. In Southern Europe, the historical legacy of authoritarianism inhibits the right and reins in a potential nationalist framing of emigration. CEE party systems serve to inhibit the left, and parties of the right shape the mainstream of the party system. There, right-wing parties took stances on emigration that utilized state interventionist and nationalist frames on the issue. Importantly, this finding is significant for understanding the success of right-wing agendas in CEE countries (Krastev and Holmes, 2019; Kelemen, 2020).

Delving deeper into our analysis of party manifestos revealed distinct patterns in how parties framed emigration. Socio-economically, this issue was most often linked with calls for improved conditions within the country through welfare state and labour market reforms. Culturally, rightist parties in the two CEE countries framed emigration as a threat to the community and nation. In Poland and Romania, the interventionist and nationalist stances of parties were most prominent, merging socio-economic concerns about emigration with its cultural impact on national demography. In Portugal, the discussion around emigration focused mainly on state interventionism in socio-economic terms, with cultural frames focusing on the diaspora, largely avoiding the topic of loss of national community.

Whilst dominant frames differed by region, with interventionist frames predominating in the south and interventionist and nationalist ones predominating in CEE, they shared one commonality: Most of them called for demarcation in economic and/or cultural terms. Applying the heuristic by Grande and Kriesi (2012), we can link these party-political discourses on emigration to responses to EU integration and globalization that call for demarcation, manifesting as a call for protection against open markets and societies (Kriesi et al., 2008, p. 9). [Corrections made on 24 October 2024, after first online publication: In the preceding sentence, in-text citation for ‘Grande and Kriesi (2012)’ has been corrected in this version.] In terms of emigration, this translates into a push for welfare state expansion and an increased focus on national community and demography. Interestingly, we found no evidence that emigration was used to justify EU scepticism. Confirming the attitudinal research of Vasilopoulou and Talving (2019), political parties do not openly criticize FMP. Thus, political parties are left with a conundrum: They must address the societal impacts of emigration (including its negative effects), whilst simultaneously acknowledging individual citizens' appreciation of EU freedoms. Thus, whilst emigration is associated with calls for demarcation, it does not extend to an explicit critique of EU integration. This has structural implications for domestic and European politics where problems emerging from market integration and membership in a multilevel polity cannot be addressed fully by either level, domestic or European (Scharpf, 2009).

How can our findings and the theory-informed conceptual framework guide future research? As a next step, we propose studying how political conflict on emigration can contribute to variations in policy change and reform. Similar to the dynamics that underlie immigration politics, distinctive interventionist and nationalist ways of dealing with the issue of emigration may change the domestic setting for emigration. Across emigration countries, efforts for socio-economic demarcation are more likely as they are emphasized in comparison with cultural demarcation. However, solving the emigration conundrum is not only a domestic issue and may also depend on more efforts at EU level to overcome the asymmetries of market integration.

Acknowledgements

The authors like to thank Michael Blauberger, Anna Kyriazi, Suat Alper Orhan and Susanne K. Schmidt for their very valuable comments on drafts of the manuscript at workshops at Bremen University and a mini symposium at CES in Iceland in 2023. Comments from colleagues at the Migration Policy Centre and the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies received during a research stay at EUI during spring 2023 greatly advanced the conceptual framework of this article. This work was supported by a grant (458587043) from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for the project ‘Paradoxes of EU freedom of movement’.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.