Clinicopathologic features and outcomes of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumour (IPT) and hepatic IPT-like lesions

Abstract

Aims

Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumours (IPTs) are nonneoplastic hepatic masses characterized by variably fibroblastic stroma and inflammatory infiltrate, hypothesized to arise as part of a response to infection or prior surgery. The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinicopathologic features and outcomes of biopsy-proven hepatic IPT as well as other cases with IPT-like histologic features.

Methods and Results

A database search at our institution identified cases with a pathologic diagnosis of hepatic IPT (n = 80) between 2000 and 2023. Histologic features (stromal quality, inflammatory cell components, granulomas, and necrosis) were evaluated. Past medical and surgical history, microbiologic studies, and outcomes were reviewed retrospectively. Patients frequently had a past medical history of malignancy (34%), biliary disease (15%), or prior intraabdominal surgery (24%), and often presented with multifocal hepatic lesions (36%). Variable inflammatory backgrounds were present, including histiocytic (36%), lymphoplasmacytic (34%), or neutrophilic (24%). Specific organisms were identified in 15% of cases, most commonly Klebsiella and Staphylococcus species. Most patients with available clinical follow-up demonstrated radiologic resolution and/or had repeat negative biopsy; a minority of patients (8%) were subsequently diagnosed with neoplastic hepatic lesions. No significant association was seen between histologic features and the subsequent clinical or pathologic diagnosis of hepatic neoplastic lesions.

Conclusions

Hepatic IPT is a heterogeneous entity that can present in a variety of clinical scenarios and show a wide morphologic spectrum. These lesions often regress spontaneously or with antibiotics. A subset of cases with hepatic IPT-like histologic features were subsequently diagnosed with malignancy, emphasizing the need for continued follow-up and repeat biopsy depending on clinical and radiologic features.

Graphical Abstract

In this retrospective study of 80 patients with biopsy-proven hepatic inflammatory pseudotumour (IPT), patients commonly have a history of biliary disease (15%) or prior intraabdominal surgery (24%). Most patients with available clinical follow-up demonstrated radiologic resolution and/or had repeat negative biopsy; a minority of patients (8%) were subsequently diagnosed with neoplastic hepatic lesions.

Abbreviations

-

- CMML

-

- Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia

-

- EBV

-

- Epstein-Barr virus

-

- GMS

-

- Grocott-Gömöri's methenamine silver

-

- HBV

-

- Hepatitis B virus

-

- HCV

-

- Hepatitis C virus

-

- IMT

-

- Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

-

- IPT

-

- Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumour

-

- MSSA

-

- Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

-

- PBC

-

- Primary biliary cholangitis

Introduction

Hepatic inflammatory pseudotumours (IPTs) are nonneoplastic hepatic masses defined by histologic features of fibroblastic or myofibroblastic stroma and variable inflammatory infiltrate. These are presumed to be reactive and are associated with a broad spectrum of aetiologies, including prior abdominal/hepatic surgery, chronic cholangitis,1 and infection.2, 3 Hepatic IPTs have been reported in the setting of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC),4 primary sclerosing cholangitis,5 and Crohn's disease.6 Hepatic IPT may regress spontaneously7, 8 or following treatment of the causative infection or injury.9 Rare recurrences have been reported.10

Given the presence of a mass lesion in the liver and the potential for local growth, hepatic IPT may be radiographically challenging to distinguish from malignant neoplastic lesions such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.11, 12

IPT may also cause diagnostic difficulty on small biopsies, since the pathologic differential diagnosis includes neoplastic entities such as lymphocyte-rich and neutrophil-rich variants of hepatocellular carcinoma, follicular dendritic cell tumour,13 angiomyolipoma,14 and lymphoproliferative disorders such as Hodgkin lymphoma. Additionally, sampling of an inflammatory rind adjacent to a malignant lesion may occasionally show IPT-like features histologically. While IPT has been historically used synonymously with inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) in some studies, IMT is a neoplasm with characteristic ALK, ROS1, and NTRK3 mutations and is now regarded as a separate entity.15, 16

Due to their potentially rapid growth, hepatic IPTs can be radiographically interpreted as an intrahepatic neoplasm17 and may occasionally show extrahepatic growth.18 These lesions are also challenging to classify histologically due to the heterogeneity of underlying disease. Some authors have proposed the subclassification of IPT as fibrohistiocytic and lymphoplasmacytic variants, the latter of which may have features that overlap with IgG4-related disease.19, 20

Overall, the outcome data in hepatic IPTs is limited. The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinicopathologic features and outcomes of biopsy-proven hepatic IPT and hepatic IPT-like lesions.

Materials and Methods

Patient selection

A retrospective review was performed to identify mass-forming hepatic lesions with a pathologic diagnosis or descriptive diagnosis favouring hepatic IPT. A natural language search was performed for the diagnosis of IPT made during 2000–2023 at the University of California, San Francisco. Cases were excluded if the slides were not available or if the pathology was diagnostic of or highly suspicious for neoplasia. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, the Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, CA).

Histological examination

All cases with a diagnosis of hepatic IPT or IPT-like features were evaluated by D.J.B. and E.D.N. Cases were subcategorized based on predominant morphology as paucicellular/sclerotic (characterized by dense fibrotic and variably hyalinized stroma with minimal associated inflammation), lymphoplasmacytic (characterized by sheets of lymphocytes or plasma cells with or without lymphoid aggregates), neutrophilic (characterized by predominantly neutrophilic inflammation), or histiocytic (characterized by variable xanthogranulomatous inflammation with or without multinucleated giant cells or admixed neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils). Cases with mixed features were categorized based on the predominant morphology. The presence or absence of the following histologic features were recorded for each case: duct damage or ductular reaction, well-formed epithelioid granulomas, prominent haemorrhage and/or hemosiderin, sinusoidal dilatation and/or hepatic plate atrophy. Special stains and immunohistochemistry were reviewed, when available.

Clinical evaluation

The patients' medical records were reviewed for features including age, gender, imaging data (including size of the lesion, location, and the presence of multifocal hepatic lesions), relevant medical history, and infectious history. Any history of malignancy, biliary disease, abdominal surgery, or cirrhosis was noted.

Follow-up data

Radiologic data after liver biopsy was evaluated when available, including progression or resolution of the biopsied mass. Patients were designated as having a “likely neoplastic” or “reactive/infectious” aetiology based on radiologic features and/or subsequent pathologic biopsies.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of categorical variables were performed using the Pearson method or Fisher's exact test when appropriate. Statistical calculation was applied using Student's t test for continuous variables. The log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used to compare the survival distribution. All statistical results were considered significant if the P value was <0.05.

Results

Clinical features

A total of 161 patients with liver biopsies or resections with a diagnosis of “IPT” were identified.

A total of 81 cases were excluded. Five cases (n = 5) were excluded in which the pathology was diagnostic of or highly suspicious for neoplasia including one case of Epstein–Barr virus-positive inflammatory follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (EBV+ IFDCS) (n = 1) and four cases (n = 4) suspicious for spindle cell neoplasm (including morphologically low-grade spindle cell neoplasm and atypical spindle cell proliferation). One case of benign biliary cyst (n = 1) was excluded. Additional cases were excluded due to lack of radiologic mass lesion correlate (n = 6) or sampling of a gallbladder mass (n = 1). The remaining cases were excluded due to unavailability of slides (including n = 1 hepatic resection suspicious for IgG4-related disease in which materials were unavailable).

The clinical features of the study cohort (n = 81) are summarized in Table 1. The diagnosis was rendered on core-needle biopsy in the majority of cases (n = 80), with one (n = 1) resection included in the study. The average age was 58.3 years (range 3–86 years), with a male predominance (66%). The masses were often identified incidentally on computed tomography (CT-) or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT (25%, n = 20), with other patients presenting with abdominal pain (24%, n = 19), fever (14%, n = 11), elevated liver enzymes (11%, n = 9), or weight loss (6%, n = 5). Patients with hepatic IPT frequently had an underlying history of malignancy (34%, n = 27), prior abdominal surgery (24%, n = 19), or biliary disease/obstruction (15%, n = 12). Cirrhosis was present in 10% (n = 8).

| Characteristics | All cases (n, %) |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 80 |

| Males | 53 (66%) |

| Females | 27 (34%) |

| Age (in years) | |

| Mean, SD | 58.5 ± 17.6 |

| Range | 3–86 |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Abdominal pain | 19 (24%) |

| Fever | 11 (14%) |

| Weight loss | 5 (6%) |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 9 (11%) |

| Incidental | 20 (25%) |

| Clinical history | |

| Cirrhosis | 8 (10%) |

| History of malignancy | 27 (34%) |

| Biliary disease or obstruction | 12 (15%) |

| Prior abdominal surgery | 19 (24%) |

Of the cases with cirrhosis (n = 8), two patients had a clinical history of hepatitis C virus (HCV), two patients had a history of alcohol-related cirrhosis, and one patient had a history of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV). In one patient, the underlying aetiology of cirrhosis was unclear, with a clinical history of diabetes type 1 as well as portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and chronic SMV thrombosis. Clinical data were insufficient in the remaining two patients.

The most common oncologic history included pancreaticobiliary neoplasm (8.8% of total cohort, n = 7) followed by lymphoproliferative disorder (7.5% of total cohort, n = 6) and genitourinary malignancy (6.3% of total cohort, n = 5 including three cases with a history of prostatic carcinoma, one case with a history of renal cell carcinoma, and one case with a history of “testicular neoplasm”). Three patients had a history of lung carcinoma (3.8% of total cohort, n = 3) and two patients had a history of colorectal carcinoma (2.5% of total cohort, n = 2) Other past medical history included metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown primary (n = 1), papillary thyroid carcinoma (n = 1), gastric “low grade myxoid tumour” (n = 1), and epithelioid sarcoma (n = 1).

The underlying cause of biliary obstruction included cholelithiasis (n = 5) and pancreaticobiliary malignancy (n = 6). One patient (n = 1) presented with recurrent pancreatitis and cholangitis after resection for congenital choledochal cyst.

Radiologic findings

The average size was 5.1 cm (range 0.8–12 cm), with multifocal lesions in 36% (n = 29) of cases (Table 2). Of the solitary lesions (n = 51), detailed radiologic reports including lesion location within the liver was available in 31 patients, with most cases seen in the right lobe (77%, n = 24 of 31) and a minority in the left lobe (23%, n = 7 of 31). A subset of cases (14%, n = 11) showed areas of peripheral enhancement/rim enhancement which raised a differential diagnosis of hepatic abscesses versus hepatic metastases. One (n = 1) peripheral lesion and no perihilar masses were identified.

| Radiologic characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total patients | 80 |

| Lesion size | |

| Average (cm), SD | 5.1 ± 3.3 cm |

| Range | 0.8–12 cm |

| Solitary lesions | 51 (64%) |

| Left lobe | 7 of 51 (14%) |

| Right lobe | 24 of 51 (47%) |

| Not specified | 20 of 51 (39%) |

| Multifocal lesions | 29 (36%) |

| Rim-enhancing/peripheral enhancement | 11 (14%) |

Microbiology studies

Of the total patients, 21 of 80 had documented microbiologic studies performed (including bacterial, mycobacterial, or fungal cultures from tissue biopsy, peripheral blood cultures, and/or tissue polymerase chain reaction, PCR) (Table 3).

| Patient | Clinical setting | Solitary or multifocal hepatic masses | Diagnostic technique | Organism(s) identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diabetic ketoacidosis | Solitary (ring enhancing) | Blood culture | Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) |

| 2 | Urinary tract infection | Multifocal (rim enhancement and surrounding parenchymal hyperenhancement) | Liver aspiration | Klebsiella oxytoca |

| 3 | Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) | Multifocal (not otherwise specified) | Tissue PCR | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| 4 | Prior cholecystectomy | Solitary (nonspecific mass, right hepatic lobe) | Liver drainage culture | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| 5 | Rectosigmoid adenocarcinoma with perforation | Solitary (heterogeneous subcapsular mass) | Liver swab | Anaerobic Gram Negative Rod not B fragilis group (beta lactamase positive) |

| 6 | Bile duct adenocarcinoma | Solitary (ill-defined, hypoattenuating) | Liver drainage culture | Mixed (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis, Klebsiella variicola, Enterococcus faecalis, and Candida. albicans) |

| 7 | B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL) | Multifocal (subcentimeter, not otherwise specified) | Tissue PCR and culture | Trichosporon asahii |

| 8 | Urinary tract infection | Solitary (heterogeneous mass) | Blood culture | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| 9 | Prior liver transplant | Multifocal (multiple hepatic hypodense lesions) | Blood culture | Vibrio cholerae |

| 10 | Prior liver transplant | Solitary (Circumscribed T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense observation) | Serum PCR | Adenovirus, Epstein–Barr virus |

| 11 | Colon perforation after colonoscopy | Solitary (not otherwise specified) | Blood culture | Streptococcus anginosus |

| 12 | Diabetes mellitus | Multifocal (not otherwise specified) | Blood culture and repeat liver biopsy | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSA) |

A specific organism was identified in 15% of all patients (n = 12) via concurrent or subsequent microbiologic assay. Of the patients with positive microbiologic assay, multifocal lesions were seen in five patients (41.7%). Six (50%) were immunocompromised (postchemotherapy or posttransplant) and two patients (16.7%) had a history of colorectal perforation.

Four of the patients (patients 1, 2, 6, and 9) had radiologic characteristics that were suspicious for infectious aetiologies (areas of rim enhancement and surrounding parenchymal hyperenhancement on postcontrast imaging and/or hypoenhancing lesions).

Blood culture or serum PCR was the most frequently positive assay (n = 6 of 12, 50%) followed by direct culture of the hepatic lesion (n = 5 of 12, 41.7%) and tissue culture/PCR of another site (n = 2 of 12, 16.7%). Patient 4 initially presented with a nonspecific mass at the right lobe and subsequently developed progressive abdominal pain, radiologic findings of fluid collection, and aspiration with culture of the organism. Patient 12 also underwent repeat biopsy due to persistent radiographic targetoid hypodensity, with moderate methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSA) growing both from culture of the liver biopsy as well as blood culture. Patient 3 presented with multiple hepatic lesions and lymphadenopathy, with PCR of a concurrent lymph node biopsy positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Patient 7 presented with multiple hepatic and skin lesions and was diagnosed with disseminated Trichosporon asahii via PCR and culture of a skin lesion. Klebsiella sp. (n = 4 of 12, 33.3%) and Staphylococcus sp. (n = 3 of 12, 25%) were commonly isolated in cases with positive microbiology.

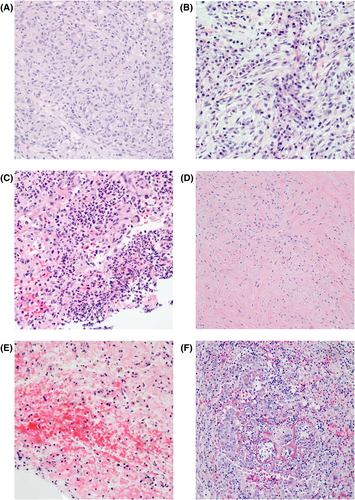

Histologic features

Histology from the liver biopsies were reviewed on all patients, including H&E-stained slides and additional histochemical and immunohistochemical stains performed for clinical diagnosis (see Figure 1; Table 4). Histiocytic (n = 29, 36%) and lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory background (n = 27, 34%) were the most common, followed by neutrophilic in 24% (n = 19) of cases and paucicellular/sclerotic in 6% (n = 5). Many of the cases with histiocytic inflammation showed either sheets of foamy macrophages or numerous histiocytes with admixed lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils, whereas well-formed granulomas were less commonly seen (n = 14, 18%). Other commonly seen features included hepatic plate atrophy (n = 20, 25%) associated haemorrhage and/or hemosiderin (n = 25, 31%), necrosis (n = 22, 28%), and ductular reaction (n = 10, 13%).

| All cases (n, %) | Histiocytic | Lympho-plasmacytic | Neutrophilic | Paucicellular/sclerotic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 80 | 29 (36%) | 27 (34%) | 19 (24%) | 5 (6) |

| Males | 53 (66%) | 22 (76%) | 14 (52%) | 15 (79%) | 2 (40%) |

| Females | 27 (34%) | 7 (24%) | 13 (48%) | 4 (21%) | 4 (60%) |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean, SD | 58.3 ± 17.6 | 62.8 ± 14 | 56.3 ± 14.5 | 62.7 ± 14.6 | 67 ± 13.1 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 19 (24%) | 10 (34%) | 5 (19%) | 3 (16%) | 1 (20%) |

| Fever | 11 (14%) | 5 (17%) | 2 (7%) | 4 (21%) | 0 (0%) |

| Weight loss | 5 (6%) | 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 9 (11%) | 6 (21%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Clinical history | |||||

| Cirrhosis | 8 (10%) | 2 (7%) | 3 (11%) | 3 (16%) | 0 (0%) |

| History of malignancy | 27 (34%) | 10 (34%) | 8 (30%) | 8 (42%) | 1 (20%) |

| Biliary disease or obstruction | 12 (15%) | 5 (17%) | 1 (4%) | 6 (32%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prior abdominal surgery | 19 (24%) | 5 (17%) | 7 (26%) | 6 (32%) | 1 (20%) |

| Histologic features | |||||

| Necrosis | 22 (28%) | 5 (17%) | 6 (22%) | 10 (53%) | 1 (20%) |

| Haemorrhage and/or hemosiderin | 25 (31%) | 4 (14%) | 11 (41%) | 9 (47%) | 1 (20%) |

| Hepatic plate atrophy | 20 (25%) | 6 (21%) | 6 (22%) | 8 (42%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ductular reaction | 10 (13%) | 5 (17%) | 3 (11%) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

Five (n = 5) cases showed paucicellular/sclerotic histologic features. Histologically, the biopsies demonstrated hypocellular proliferation of bland-spindled cells with sclerotic, hyalinized, and variably edematous stroma without obliterative phlebitis or storiform fibrosis. No overt cytologic atypia or mitotic activity was present in any of these cases. Preserved portal tracts were noted within lesional biopsies, some with entrapped bile ducts within the lesion. Immunohistochemistry for ALK1 was performed in three of five cases with paucicellular/sclerotic stroma to evaluate for IMT and was negative.

One case (n = 1) showed features suggestive of IgG4-related disease including storiform fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis. A histiocytic-predominant background was noted including well-formed granulomas in addition to plasma cells and lymphocytes.

Half of the cases with positive clinical microbiologic studies (6 of 12, 50%) showed histiocytic predominant inflammation, including three cases with bacterial organisms (including one case each with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus anginosus, and Klebsiella pneumonia).

No parasitic organisms were identified in any of the cases. Polarizable foreign-material suggestive of prior stones was seen in one case with a clinical history of prior cholecystectomy and stent placement, and foreign-body giant cell reaction with associated vegetable matter was present in one case with a history of prior colorectal perforation.

Histochemistry, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridization

Immunohistochemistry was often performed to exclude other entities with similar morphology (Table 5). Stains performed that were negative include ALK (to exclude IMT, n = 43), pankeratin (to exclude carcinoma, n = 25), HMB-45 (to exclude inflammatory angiomyolipoma, n = 13), CD1a (to exclude interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma, n = 14), CD34 (to exclude solitary fibrous tumour and peripheral nerve tumours, n = 25), and CD117/DOG1 (to exclude gastrointestinal stromal tumour (n = 18). Stains performed to evaluate for lymphoproliferative disorders (CD3, n = 29; CD20/PAX5, n = 23; CD21/CD23, n = 23; kappa/lambda, n = 23; and CD30, n = 7) showed no evidence of abnormal lymphoid proliferation.

| Cases stained % of total (n) | |

|---|---|

| Stains | |

| Pankeratin | 31% (25) |

| Hematolymphoid stains | |

| CD3 | 36% (29) |

| CD20 or PAX5 | 38% (30) |

| CD21 or CD23 | 29% (23) |

| CD1a | 8% (6) |

| ALK | 54% (43) |

| CD30 | 9% (7) |

| Kappa/lambda | 29% (23) |

| Mesenchymal markers | |

| HMB-45 | 16% (13) |

| S-100 | 18% (14) |

| SMA | 31% (25) |

| Desmin | 18% (14) |

| CD34 | 31% (25) |

| CD117 or DOG1 | 23% (18) |

| Infectious markers | |

| GMS | 45% (36) |

| AFB | 60% (48) |

| T. pallidum | 18% (14) |

| EBV in situ hybridization | 25% (20) |

IgG and IgG4 were performed in n = 11 of 26 cases, with an average of 15.6 IgG4-positive cells per high-power field. Material was unavailable to perform immunohistochemistry for IgG or IgG4 on the case (n = 1) with storiform fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis. All cases stained demonstrated an IgG4-to-IgG ratio of less than 40%.

Infectious special stains were commonly performed to exclude infectious aetiologies, including acid-fast bacteria (AFB) stain (n = 48), immunohistochemistry for Treponema pallidium (n = 14) and in situ hybridization for Epstein–Barr virus (n = 20), all of which were negative. Grocott–Gömöri's methenamine silver stain (GMS) was performed in 36 cases; 35 of these cases were negative, and one case displayed rare budding yeast.

Follow-up clinical data and outcome

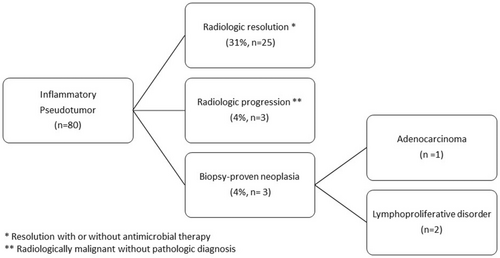

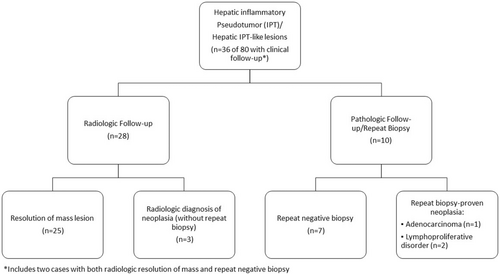

Detailed clinical information with follow-up data was available in 36 patients (45%) (Figure 2, Table 6). Repeat biopsies were performed on 12 patients (15%), with follow-up radiologic imaging in 29 patients (36%). The details of follow-up data are summarized in Figure 2.

| Characteristics | Reactive/resolving (n = 30) | Neoplastic (n = 6) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | 63.5 | 60.4 | 0.70 |

| Male gender % (n) | 60% (18) | 100% (6) | 0.08 |

| Clinical features | |||

| Fever | 23% (7) | 0 (0%) | 0.32 |

| Prior history of malignancy | 40% (12) | 83% (5) | 0.08 |

| History biliary obstruction | 20% (6) | 16% (1) | 1.00 |

| Solitary lesions | 60% (18) | 66% (4) | 1.0 |

| Lesion size (average) | 4.4 cm | 4.0 cm | 0.73 |

| Positive microbiology | 40% (12) | 0 (0%) | 0.07 |

| Histologic features | |||

| Inflammatory background | |||

| Lymphoplasmacytic | 10 (33%) | 3 (50%) | 0.69 |

| Histiocytic | 11 (37%) | 0 (0%) | 0.15 |

| Neutrophilic | 9 (30%) | 1 (17%) | 0.65 |

| Paucicellular/sclerotic | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) | 0.17 |

- * Reactive/resolving or neoplastic based on follow-up pathologic and/or radiologic follow-up data.

Of the patients with clinical follow-up (n = 36), most patients were clinically determined to be either infectious or reactive in aetiology (83%, n = 30), based on radiologic resolution (69%, n = 25 of 36) and/or repeat negative biopsies (19%, 7 of 36). Antimicrobial therapy was documented prior to resolution of the lesion in 17% (5 of 29) of patients with presumed reactive lesions, and was given either empirically or in response to positive microbiologic testing (Table 3).

A minority of patients (n = 6 of 80 total cohort, 8%) were subsequently clinically or pathologically diagnosed with neoplastic hepatic lesions. Of the six cases initially diagnosed with IPT or IPT-like lesion in the lesion, this represented hepatic involvement by the patient's known underlying malignancy in 66.7% (four of six patients).

Three cases had follow-up biopsies with malignancy. Two patients (n = 2) had repeat biopsies demonstrating lymphoproliferative disorder, including one repeat liver biopsy demonstrating prominent lymphoid aggregates with positive B-cell clonality for a new diagnosis of malignancy. A second case with repeat liver biopsy demonstrated involvement of the patient's known peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL, NOS). A third patient (n = 1) showed radiologic progression with a repeat fine-needle aspiration of the liver demonstrating metastatic adenocarcinoma of the patient's known pancreatic primary.

The remaining three patients (n = 3) were categorized as likely neoplastic based on radiologic progression and clinical management. Two patients with a history of abdominal sarcoma (n = 1 with epithelioid sarcoma and n = 1 with type not specified) showed radiologic progression of the hepatic lesion(s), and were clinically managed with additional systemic chemotherapy without repeat biopsy. One patient with a history of HCV and cirrhosis was diagnosed as multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma based on radiologic findings.

The clinical, radiologic and histologic features of likely reactive/infectious cases (n = 29) and likely neoplastic cases (n = 6) are summarized in Table 6. Tumour size and focality were similar, as well as histologic features. The positive microbiologic cultures were exclusively seen in reactive/infectious lesions.

Discussion

This retrospective study confirms the diverse clinical settings in which hepatic IPT and hepatic IPT-like lesions are observed. Our results show that a specific organism is identified in a small minority of cases (15%) of patients via concurrent or subsequent microbiologic assay, including positive testing for Klebsiella, S. aureus, and mixed bacterial flora. These are similar organisms as can be seen in hepatic abscesses,21, 22 suggesting that a subset of hepatic IPTs can arise either concurrently with or in reaction to hepatic abscesses. A subset of cases (13.8%, n = 11) showed areas of peripheral enhancement/rim enhancement radiographically. The findings in our study support the conclusions previously published by Arora et al.2 that a subset of hepatic IPT may represent mass-forming inflammatory rind adjacent to an abscess. Only one case showed rare budding yeast on GMS stain, possibly representing contaminant. This low sensitivity of special stains to detect organisms emphasizes the importance of collecting tissue samples for testing and culture if a hepatic IPT is suspected.

Hepatic trauma including iatrogenic forms of injury is a known risk factor for the development of hepatic abscess.23 In our study, more than one-third of patients either had prior abdominal surgery (24%) or biliary process/obstruction (15%). The predominant location (79%) of solitary lesions in the right lobe may additionally support biliary obstruction as an underlying cause in these cases, and the presence of haemorrhage and/or hemosiderin in nearly one-third of the cases is also suggestive of prior injury in these lesions.

IgG4-related disease is a well-described cause of mass-forming hepatic IPT with characteristic histologic features of IgG4-positive plasma cell-rich infiltration and obliterative phlebitis.19, 24, 25 Some authors have proposed a classification of hepatic IPTs into lymphoplasmacytic and fibrohistiocytic types, suggestive that lymphoplasmacytic IPT corresponds to IgG4-related disease.19 A subset of cases in this study showed prominent lymphoplasmacytic inflammation in the stroma but had lesions confined to the liver, which resolved radiographically without steroid treatment, findings that would not be expected in IgG4-related disease.26

Our study is limited by data available via retrospective review, as well as the unavailability of material to uniformly complete diagnostic immunohistochemistry and special stains on all cases. While no diagnostic cases of IgG4-related disease were identified in our cohort, one case showed characteristic morphologic features but the diagnosis could not be confirmed due to lack of clinical information and additional material for stains. While IgG4-related disease should always be considered in the differential diagnosis in IPT with a prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, it is important to emphasize that prominent IgG4-positive plasma cells have been reported in a variety of inflammatory conditions without systemic features of IgG4-related disease, including primary sclerosing cholangitis.27 IgG4-positive cells may occasionally present as part of an inflammatory response without features of IgG4-related disease, and emphasizes the importance of excluding reactive conditions as part of a clinical work-up for IgG4-related disease. Correlation with other morphologic features such a storiform fibrosis, obliterative phlebitis, and IgG4 to IgG ratio of more than 0.4, along with the serum IgG4 levels and overall clinical setting, is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of IgG4-RD.28, 29

The strength of this retrospective study is the clinical follow-up data demonstrating the heterogeneity of cases with hepatic IPT-like features. Of the cases with clinical follow-up, the majority (83%) were clinically determined to be either infectious or reactive in aetiology based on radiologic resolution. A minority of the total patients in this study (8%) had either radiographic progression of the biopsied lesion or biopsy-proven malignancy on a subsequent biopsy, two of which were lymphoproliferative disorder. We have included these cases with a diagnosis of IPT or IPT-like lesion on hepatic biopsy that ultimately were pathologically proven or highly radiographically suspicious in order to highlight how the fibroinflammatory rind adjacent to undersampled neoplastic lesions may occasionally demonstrate IPT-like features. Pathologists should be careful rendering a definitive diagnosis of hepatic IPT without careful correlation with radiologic findings and procedural notes to confirm that the sample is representative of the lesion. Nonetheless, the diagnostic use of hepatic IPT is advised in the appropriate clinical context in order to spare the patient from unnecessary liver resection.30, 31

In conclusion, hepatic IPT remains a diagnosis of exclusion, in which other potential neoplastic aetiologies (e.g. IMT) should be excluded. Our study also suggests that hepatic IPT-like features may be seen adjacent to unsampled or undersampled malignancy. Therefore, clinicians should continue to monitor patients clinically and radiographically and consider repeat biopsy in persistent lesions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the UCSF Department of Pathology for administrative support.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no disclosures.

Funding information

This research did not receive any grants from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Author contributions

Eric Nguyen: Conceptualization, methodology, slide review, data curation, formal analysis, and writing—review and editing. Kwun Wah Wen: Conceptualization, methodology, review, and editing. Sanjay Kakar: Methodology, review, and editing. Dana J. Balitzer: Conceptualization, methodology, slide review, data curation, formal analysis, and writing—review and editing.

Open Research

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.