Sectoral Challenges: Exploring Regulatory Dialectics in Charity Performance Reporting Regulation

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

To reduce information asymmetry and maintain public trust in charities, they are strongly encouraged to communicate their good work, with many jurisdictions considering whether and how to regulate performance reporting. New Zealand and the United Kingdom are early developers of new governance-type performance reporting requirements—using co-regulatory tools to enhance the regulators’ legitimacy and thus, charities’ compliance. We explore how this regulation has developed, framing our analysis with Kane's regulatory dialectics, which argue that regulation is developed through a series of repeated, cyclical (often antagonistic) interactions between regulators and regulatees. We find that new governance-type performance reporting regulation exemplifies the stages of Kane's regulatory dialectics but that important differences associated with new governance regulation led to a more partnered and less adversarial process. When repeated interactions are facilitated through co-regulation, regulatee representation on regulatory bodies, formal and informal interactions, and regulatee advocacy for regulatory developments, the boundaries between regulator and regulatee become blurred. This impacts significantly on the resulting regulation and potentially improves acceptance of (and compliance with) mandatory requirements. We propose a model of new governance regulatory dialectics that can support practitioners in developing new governance regulation, and further research and theorization of this important area.

1 Introduction

The changing policy environment has increased government intervention to the nonprofit sector generally, with new legal frameworks, legislation, and, in some cases, new requirements to register and file information (Pape et al. 2020). Regulation in Black's Law Dictionary is defined as “the act or process of controlling by rule or restriction”1 indicating that a multitude of structures and processes can meet diverse policy aims. Pape et al. (2020) note that regulators, along with philanthropists and donors, are grappling with how best to encourage charities (a nonprofit organizational subsector) to report on the difference they have made. Improvements in performance reporting would enable charities to counter criticisms of poor management and ineffectiveness, enabling funders to make more informed decisions. We explore how regulation has been developed to reduce information asymmetry in performance reporting, thus meeting resource providers’ needs and encouraging better management within charities.

Performance reports can include information on outputs (immediate or direct products and services delivered by a charity), outcomes (charities’ impact on beneficiaries and society), efficiency (ratios of inputs against outputs), and effectiveness (comparison of performance to targets). However, research suggests that charities in this large and extremely diverse sector face significant methodological and resource-based challenges in measuring and reporting performance (Chaidali et al. 2022). Further, they avoid reporting “bad news,” preferring instead to use performance reporting to “market” themselves well (Dhanani and Connolly 2012). Combined, these challenges inhibit voluntary reporting. As a result, and after charity scandals threatening public trust and confidence (Connolly et al. 2021), regulation of performance reporting has been advanced as a means “to emphasise the necessity of greater transparency demanded by society and media” (Connolly et al. 2021, 33). The United Kingdom (UK) and New Zealand (NZ) are early developers of performance reporting regulation, with emerging evidence suggesting that this has increased the incidence and quality of charities’ performance reporting (e.g., Chaidali et al. 2022), with potential benefits for public trust and confidence.

McConville and Cordery (2018) illustrate a spectrum of different jurisdictions’ efforts to regulate charities’ performance reporting, identifying “command and control” and “market-based” approaches with “new governance” as a third approach between these two traditional extremes (Sinclair 1997; Trubek and Trubek 2007). Bryson et al. (2014) argue that new governance approaches can cocreate public good and achieve social objectives, with McConville and Cordery (2018) citing NZ and the UK as examples. The UK's charity regulation is widely influential. For example, McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt (2017) describe the Charity Commission of England and Wales (CCEW) as the “mother of charity regulators” and note that government strengthened its regulatory powers from 2016. Drawing heavily on the UK model, NZ's Charities Commission was established in 2005, being subsumed by government in 2012; hence, both the UK and NZ's regulators are government operated.

Presuming public interest in more efficient resource provision (whatever the sector), regulatory reform attempts to address information asymmetry issues and thus to enhance market-based trust, reduce private interest in resource redistribution, and reduce unintended consequences (Hertog 1999; McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt 2017). These aspirations are reflected in many jurisdictions seeking “better regulation” (BR) in the public interest (Radaelli and Meuwese 2009). Yet Radaelli and Meuwese (2009, 639) state that the discourse of BR is “more popular than BR activities” highlighting the difficult passage of regulatory reform which must gain legitimacy with regulatees before they agree to comply. Failing legitimacy, stakeholders demand deregulation, better evidence, and/or participation in regulatory efforts (Bunea and Ibenskas 2017). Yet, there is limited literature on how (as contrasted to a larger literature on why) regulation develops. Kane's model of regulatory dialectics (Kane 1977, 1980, 1983) is commonly used to describe the process through which economic regulation can introduce the public interest (rather than private interest) by focusing on reducing information asymmetry and improving resource provision through creating a trusted marketplace (Hertog 1999; McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt 2017). Although regulatory dialectics is used extensively to explain banking regulation (see, e.g., Gerding 2016; Kane 2007), it has also been applied to regulatory change elsewhere. For example, Urueña (2012, 295) describes Colombian water supply regulation as a “dialectic coat of many colors,” combining social transformation and redistribution, multiple regulators, and a regulatee forum (Urueña 2012). This and other examples of social and economic regulatory reform suggest that new governance approaches may also utilize a dialectic model, as we explore.

Recognizing that developing legitimate regulation is challenging generally (Bunea and Ibenskas 2017; Hertog 1999; Radaelli and Meuwese 2009) and that regulation of charity performance reporting is particularly challenging for charity regulators and the sector as a whole (McGregor-Lowndes and Wyatt 2017), this article responds to the call for more comparative in-depth case studies of regulatory reform (Bryson et al. 2015). The objective of this article is to explore how the UK and NZ developed new governance-type regulation of charity performance reporting. Responding to calls for further theorization of new governance (Bryson et al. 2015) and aiming to show legitimation in regulatory reform that enhances resource provision in the public interest, we frame our analysis utilizing Kane's (1977, 1980, 1983) regulatory dialectics. We contribute to regulatory literature by developing a model of new governance regulatory dialectics and to nonprofit/charity regulation research, areas described as under-theorized (Bryson et al. 2015; O'Toole 2014). The learnings from regulatory development should be useful for regulators and the charity sector generally, particularly in jurisdictions seeking to encourage performance reporting in line with stakeholders’ demands.

The article first describes the UK and NZ contexts, before presenting the literature on new governance in charity regulation, the theoretical framework for analysis, and the methods. Our findings on how regulation has developed are discussed, and we offer a model of how new governance regulation develops as illustrated by our case study. Conclusions are presented alongside limitations and areas for further research.

2 Context

2.1 Regulation of Performance Reporting in the UK

The CCEW was founded in 1853, and charities have been required to keep accounting records and prepare financial reports since 1960 (Cordery and Baskerville 2007). In the early 1980s, research highlighted failures in financial reporting practices and performance reporting (Bird and Morgan-Jones 1981). The Accounting Standards Committee (ASC) responded by establishing a charity working committee, including representatives of the accounting profession, charities, foundations, and an assistant charity commissioner to develop an accounting standard. They consulted through a discussion work and exposure draft (ED). The resulting (1988) Statement of Recommended Practice (SORP) focused on financial reporting, with the omission of performance reporting criticized in sector comment and academic research (Hyndman 1990).

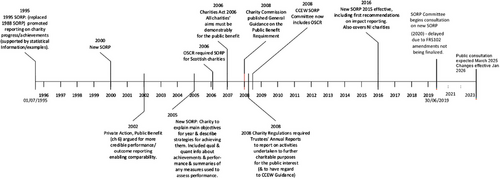

To address these critiques, the SORP has changed dramatically, gaining enhanced legislative and regulatory support. From 1990, responsibility for driving the SORP revision process passed to the CCEW's SORP Committee. Subsequent to SORPs in 1995, 2000, and 2005, the 2015 (current) SORP was issued jointly with the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR). The present position, recently clarified by the Independent Oversight Panel (2019), is that the SORP-making body comprises CCEW, OSCR, and the Charity Commission for Northern Ireland (CCNI), with the SORP Committee as an advisory committee to the regulators. The now Financial Reporting Council (FRC—formerly ASC) grants the SORP-making body its status, specifies requirements for committee representation and consultations (including EDs), and ultimately provides negative assurance (or not) on the SORP's compliance with underlying accounting standards. Legislative changes through various Charities Acts since the 1995 SORP have effectively mandated SORP compliance for most large charities in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland: Presently, non-company charities with incomes of £250,000 or less are not required to follow the SORP. Charities must register with the relevant regulators (CCEW, OSCR, and CCNI), which have a statutory objective to increase trust and confidence in charities (Cordery and Deguchi 2018) and publish charities’ annual Financial Statements and Trustees’ Annual Reports (TAR) on their websites.

SORP iterations have increased the performance reporting recommendations on the large charities that must follow the SORP. The 1995 SORP recommended reporting of achievements, examples, and statistical information where available in charities’ TARs (CCEW 1995), as did the 2000 SORP (CCEW 2000). However, in response to stakeholders’ concerns that charities’ poor reporting required a stronger regulatory response, SORP 2005 promoted more disclosure on charities’ activities, performance against objectives, and broader achievements (CCEW 2005). SORP 2015 further encouraged larger charities to report on the impact of their activities (CCEW and OSCR, 2015), reflecting continued stakeholder demands and research highlighting charities’ poor reporting.

Although requiring performance reports, the SORP does not mandate specific measures, instead encouraging charities to “tell their story.” Thus, UK regulators do not monitor or censure charities’ failure to report on performance. The content of TARs is not required to be audited (FRC 2017), nor has compliance with the SORP's recommendations been attested to. Despite this, research indicates that UK charities’ performance reporting volume and quality have increased, particularly after the 2005 SORP (see: Chaidali et al. 2022; Connolly and Hyndman 2013; Hyndman 1990; Hyndman and McConville 2018). Figure 1 provides a synopsis of the regulatory changes. Following a review of SORP governance (Independent Oversight Panel 2019) and ongoing development, exposure of a new SORP is expected in 2025.

2.2 Regulation of Performance Reporting in NZ

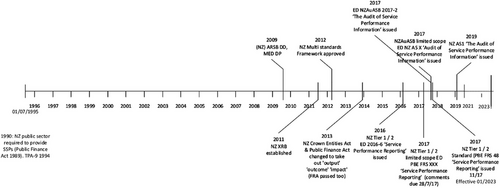

Since 1990, nonprofit entities in NZ were encouraged to report on performance in a Statement of Service Performance (SSP), a mandatory report for public sector entities (under the Public Finance Act 1989 and conceptual framework and standard on presentation (FRS-2)) (Neale and Pallot 2001). However, charities rarely voluntarily published SSPs. The Charities Act 2005 established NZ's charity regulator (Charities Commission, later Charities Services [CS]) which took registrations from mid-2007 but did not require performance reporting.

A restructure of accounting standard setting away from the profession led to the Accounting Standards Review Board (ASRB) being reestablished as the External Reporting Board (XRB) in 2011, with two sub-boards responsible for developing accounting and auditing standards, respectively (Cordery and Simpkins 2016).2 The ASRB and XRB successively consulted on a new accounting standards framework, including a requirement for all charities to publish an SSP (ASRB 2009; XRB 2011). The XRB carried over prior requirements for performance reporting, beginning work on a new standard and relevant guides, finally approving a standard for performance reporting for charities (and the public sector) in late 2017 to take effect from 20213. While requiring an SSP, like the UK SORP, this principle-based standard encourages charities to tell their own story, does not require reporting of specific measures, and eschews terms such as output and impact. Unlike the UK, these statements must be audited for the largest charities (presently those with income of $1.2 million or more) and are subject to auditor review with income of $500,000 or more; therefore, an accompanying audit standard was also developed and released in February 2019.4 Figure 2 provides a synopsis of these regulatory developments.

3 New Governance in Charity Regulation

New governance is situated between the two extremes of command and control and market-based regulation (Sinclair 1997; Trubek and Trubek 2007). Command and control approaches typically involve a legal or mandatory requirement (e.g., to register with a regulator or comply with accounting standards: Lim and Prakash 2014) with detailed specifications against which compliance can be monitored or audited, enabling penalties to be applied (Breen 2009). While focused on effectiveness, it can lead to inflexible and costly regulation (Lim and Prakash 2014). Mandated public sector performance reporting suffered this fate, becoming “boilerplate,” reducing performance accountability in NZ (Neale and Pallot 2001) and the UK (Boyne et al. 2002).

At the other extreme, potential regulators allow the market to decide appropriate “regulatory” levels. Nonprofit examples include (voluntary) self-regulation (Lim and Prakash 2014), accountability “clubs” (Gugerty 2010; Sidel 2005), third-party quality certification (Bies 2010; Tremblay-Boire et al. 2016), and codes of conduct (Bies 2010; Sidel 2005). These may be developed by charities or regulatory entrepreneurs (McConville and Cordery 2018; Sidel 2005), who decide what they perceive to be donor-useful information which they encourage charities to publish (Gordon et al. 2009). However, challenges with these market solutions include cost (Sidel 2005), exclusion of smaller charities (Tremblay-Boire et al. 2016), and promotion of simple metrics (such as conversion ratios) with dysfunctional consequences (Tinkelman 2009).

New governance mediates these “extremes” by using different tools and engaging more participants in co-regulation (Trubek and Trubek 2007). Phillips (2012, 814) defines it as “a collective action by a significant number of non-state actors to shape their own behavior and that of others in a (sub)sector through the establishment of norms, standards and credible commitments.” New governance “blurs boundaries” between regulatory actors’ roles, regulatory stages and modes, and regulatory regimes’ functions and structures (Solomon 2010). Salamon (2002, 8) defines its base theories as principal-agent and networking, noting its distinguishing factors are the “distinctive tools or instruments through which public purposes are pursued.” Hence, Bryson et al. (2014) identify new governance's key attributes as being open to influence via dialog and deliberation, using diverse approaches to know and respond across sectors based on shared public values. Although this co-creation approach sounds ideal, it is not without challenges, with Young et al. (2020, 481) opining that regulators’ process-orientated approaches may sideline stakeholders’ incompatible views and engagement with networks may fail “unless the existing subtle or hidden power imbalances inherent in the systems are addressed.”

Notwithstanding, others argue that new governance yields the benefits of both market-based and command and control regulation, perhaps due to its principal-agent roots. Benefits include flexibility and cost-effectiveness (Hepburn n.d.), utilizing networks to harness industry expertise and resource (Solomon 2010), combined with coercive compliance, retaining enforcement as a potent fallback (Harrow 2006; Trubek and Trubek 2007). It is perceived as more light-handed than command and control, and more effective than self-regulation (Solomon 2010), through engagement with knowledgeable actors who are committed to regulation and can encourage others to comply (Harrow 2006; Hepburn n.d.; Phillips 2012; Trubek and Trubek 2007). Salamon (2002) suggests that, in engaging with networks, new governance can recognize plurality, multiple private interests, and asymmetric interdependencies, but that their dynamism must be well managed for successful reform and ongoing relationships.

Hence, practical and logistical difficulties cannot be overlooked such as the need for relevant actor participation through appropriate institutional arrangements, managing conflicting voices, addressing potential for capture, building legitimacy, and controlling time and cost logistics (Baldwin 2019; Gugerty 2010; Phillips 2012). Addressing these issues is a complex balancing act (Salamon 2002). Effective regulation requires competent regulators that regulatees believe to be legitimate (Amirkhanyan et al. 2017; Phillips 2012), and who engage and connect with key stakeholders to avoid the need to revert to strict command and control (Phillips 2012; Solomon 2010).

Solomon (2010) argues the necessity of analyzing how new governance regulation develops and where and how it succeeds, with O'Toole (2014) seeking closer attention to theory in analyzing such networked behavior. Our research focuses on a regulatory development process that seeks to address principal-agent issues of information asymmetry and thus to enhance market-based trust (Salamon 2002). It assumes reform seeks the public interest (Radaelli and Meuwese 2009) aiming to achieve resource providers’ goals of understanding charities’ performance “stories” (Pape et al. 2020). Our analysis builds on prior literature and Kane's regulatory dialectics as a model of regulatory development in the public interest. We adapt his model to reflect the distinct aspects of new governance and regulatory reform (e.g., Amirkhanyan et al. 2017; Baldwin 2019; Gugerty 2010; Phillips 2012; Salamon 2002; Young et al. 2020).

4 Regulatory Dialectics

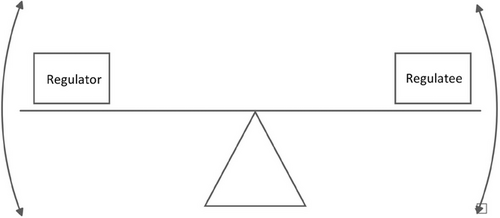

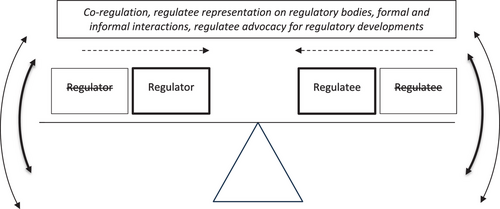

Regulatory dialectics (Kane 1977, 1980, 1983) models how regulation develops. Created to explain traditional command and control banking regulation, the model argues that a regulatory dialectic is initiated by political demanders (the public, interested parties) who lobby government to change the “rules” in their favor (Kane 1977). Regulation is created (thesis), and regulatees respond (antithesis), often avoiding unpalatable regulation, generating undesirable effects, and/or conflicting responses that lead regulators to reregulate. Reregulation brings the synthesis stage, before conflict restarts the cycle (Kane 1983). Crucially, these repeating stages of regulatory avoidance and reregulation are “opposing forces that, like riders on a seesaw, adapt continually to each other… with stationary equilibrium virtually impossible” (Kane 1980, 355). This model identifies an endless series of responses and revisions emphasizing the “tensions, paradoxes, and ambiguities inherent in efforts for regulators to impose restraints on persons and institutions” (Kane 1980, 355). Thus, O'Toole (2014) notes that those seeking to regulate ignore networks at their peril, citing stalemate and inaction, clashes with non-public actors, and reduced effectiveness. Stakeholder interactions are central to both Kane's model of the making of regulation and new governance, as discussed in the preceding section.

Regulators and regulatees utilize a range of tools in their repeated interactions. Regulators can enforce extant reporting requirements, address noncompliance through increased penalties and additional control activities, or reregulate. However, “trying to close loopholes tends to transform what may have initially appeared as a simple and tightly targeted set of regulations into a complex and wide-ranging network of governmental interference” (Kane 1980, 363) potentially harming legitimacy. Therefore, regulators also use “softer” methods of suasion, including (Kane 1977): moral suasion (exhorting specific behavior rather than penalizing noncompliance); explicit suasion (formal communications encouraging compliance); and reputed suasion (using rumors of explicit suasion to encourage compliance). Reflecting Radaelli and Meuwese's (2009) comment that discourse on “BR” is more palatable than action, Kane (1983) suggests regulatees respond in one or more of three possible ways. First, they may locate and exploit loopholes to circumvent regulation, avoid regulation completely, or comply at minimum levels. Second, through regulatory migration, regulatees move to a more favorable regulatory environment (albeit this would be difficult for a charity seeking to raise funds and operate in a specific jurisdiction). Lastly, regulatees can collaborate with others to force regulatory changes.

Hence, Kane's model perceives regulation as a dialectical process, rather than a thesis isolated from past processes. Interactions are noncontiguous and lagged (albeit that regulatees respond more rapidly than regulators: Kane 1980) with regulators and regulatees pursuing their own private interests/objectives, conditioned by expectations of the other. Importantly, regulators’ and regulatees’ respective positions and problems are “rooted in the detailed history of their prior conflict” making rooting “policies in concepts of stationary equilibrium” unreliable (Kane 1980, 333). Repeated interaction, response, and revision are key to this regulatory development and are also relevant to the need in new governance to work actively in the network (Phillips 2012; Salamon 2002).

5 Method

Earlier, we presented the context of the UK and NZ as proponents of a new governance approach to charity performance regulation. Our objective here is to undertake a comparative in-depth case study of regulatory reform to explore how new governance-type regulation of charity performance reporting has developed in these jurisdictions. In response to calls for further theorization of new governance (Bryson et al. 2015), we adapt Kane's (Kane 1977, 1980, 1983) regulatory dialectics to frame our analysis.

We reviewed relevant literature for background detail, interview themes, and later triangulation of interview data, adding literature and documents during our study. Literature included previous empirical work, publications by interest groups, acts/regulations, consultation responses, and information available on regulators’ websites.5

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with knowledgeable actors engaged in regulation over many years in NZ and the UK. These were conducted in 2017 and 2018 (see Appendix), dates that align with the most significant recent regulation in each jurisdiction, after the release of the 2015 UK SORP (see Figure 1) and 2017 NZ Standard on Service Reporting and Performance (see Figure 2). Interviewees were identified through the literature review and snowball sampling as well as, in NZ, one of the authors’ connections through involvement in standard-setting in the formative years of the XRB (but not during the standards’ completion or progress of this research). Interview guides, based on our theoretical frame and literature review themes, were sent before each interview to prompt interviewees’ recollection of historical events. In addition to questions of fact, including how the regulation was developed and how engagement was facilitated, questions explored interviewees’ perceptions of the success of such engagements and the tone of such engagements (as summarized in the Appendix). Semi-structured questions encouraged conversation, offering the interviewee the opportunity to speak freely about their recollections and to reduce possible response bias. Prompts were designed and used to explore answers more fully and to test the interviewer's understanding.

Over the 2 jurisdictions, we conducted 19 interviews, with a summary of each interviewee's background in the Appendix. Interviewees tended to be from regulatory bodies, government departments and sector bodies representing charities. Individual charities are seldom involved in the regulatory process in either jurisdiction. We adhered to University ethics requirements throughout data collection and analysis, with interviewees promised confidentiality. Thus, we anonymize their contributions. The interviews ranged from a 1/2 to 2 h in length and were transcribed and annotated with contemporaneous field notes. Transcripts were analyzed by both authors using theme-based manual coding and interpretation, guided by our regulatory dialectics framing. Examples of these themes are provided in the findings, along with representative direct quotes (identified by sequential interviewee number). Aware of the potential for bias, omissions, and errors in interviewees’ recollection, our document analysis and development of timelines enabled triangulation and continued critical review of the interviewees’ comments and relevant documents. The same process, and manual coding by both authors, allowed us to address our own potential biases in analysis, which could have resulted from previous research in the area or our (at that stage) limited engagement in standard setting by one of the authors.

6 Findings on the Process of Regulatory Change

This section explores how new governance-type regulation of charity performance reporting has developed in the UK and NZ, framed through our adaptation of Kane's (1977, 1980, 1983) regulatory dialectics. First, we identify how co-regulation develops between regulatory bodies, before Section 6.2 suggests that resource constraints influence this approach and lead to blurred boundaries between the regulator and regulatee—both contrasting to Kane's model. Yet the following subsection analyzes the regulatory dialectic in these new governance cases, setting out how this occurs but also highlighting the necessity of a regulatory dialectic in new governance regulation. We show in Section 6.4 that engaged regulatees partner in regulation by encouraging compliance with regulation and best practice reporting. We conclude this section by summarizing how the regulatory dialectic observed in our new governance cases converges and diverges with Kane's model. On the basis of this, we propose a model of new governance regulatory dialectics, drawing on data from our in-depth comparative case study and illustrating this with an example.

6.1 Co-Regulation Evidenced in Contrast to Kane's Adversarial Model

Figures 1 and 2 show that the regulation of charity performance reporting sits at the cross section of two existing regulatory frameworks: accounting and reporting in the form of accounting standards and charity regulation. Each country developed slightly different approaches: the UK created a specific body (the SORP Committee) facilitated by charity regulators, with the SORP subject to the accounting standard setter's approval. Conversely, NZ's existing auditing and accounting standard setters created the performance reporting standard (with subcommittee/working group assistance). We consider both organizations to be “regulators” per Kane's model. While using regulatory tools and suasion, the charity performance reporting context engenders several differences compared to Kane's banking regulators.

I think there was a feeling that, actually, what the SORP was proposing could've been better. You know, if it came down to it, we [the FRC] couldn't actually not approve the consultation, but we negotiated and came to an agreed position. (UK Int X6)

This suggests co-regulation between the charity regulators and the FRC, as defined by Trubek and Trubek (2007), bringing in networks per new governance regulation (Salamon 2002; Phillips 2012) but at odds with the easily identifiable regulators in Kane's context.

…It wasn't non-discrimination, but it was regulatory consistency across sectors…So, the fact that you were a charity didn't matter…you should report in the same way as these government agencies or businesses. (NZ Int 7)

Regulatory efficiency may also have driven the use of existing structures. XRB oversight facilitated the creation of an audit standard, largely in parallel with the reporting standard (NZ Int 2), through NZASB and NZAuASB working groups and subcommittees. As NZ's charity regulator (CS) was established much later than CCEW, it lacked the same formal role in the creation of performance reporting regulation—although CS was represented on subcommittees (see later).

Such broad engagement in regulation mirrors new governance regulation, in contrast to traditional regulatory dialectics based on command and control with a strong single regulator and adversarial relationships. This influences the dialectic that is then observed.

6.2 New Governance Regulators’ Responses to Inability to Monitor and Enforce Regulation

…XRB is this light-handed regulator that simply doesn't monitor and enforce, it simply sets the standards. I mean of course there is a difference in regulatory culture… [With the Financial Markets Conduct] Act you're talking about millions of dollars as the maximum fines…and that framework for enforcement doesn't really exist [in the Charities Act] … (NZ Int 3)

The NZ experience is reflected in the UK; the SORP Committee is unable to monitor or enforce compliance, and charity regulators’ capacities are also severely limited, both in law and financially. These regulators (like CCEW) must find alternative means to promote and encourage compliance.

In charity performance reporting, regulatees—charities—are actively involved in the regulatory body or its subcommittees, “blurring boundaries” between regulator and regulatee (Solomon 2010), as new governance approaches expect. Specifically, this includes numerous “peak” or umbrella sector bodies, active in different parts of the sector, which represent the views of the ultimate regulatees (individual charities).

I don't think I've been in a conversation where somebody has said, “Oh, no, don't include X [person],” or “You don't wanna hear what Y says.” I think the attitude of the people around the table is very much about not creating an echo chamber, hearing what actually is important. (UK Int 1)

So, if you wanted to create a system which is extremely effective at giving the appearances of openness and inclusion, but in practice, having the opposite effect, it would look remarkably like SORP… (UK Int 2)

We always drew back from requiring outcome/impact reporting…We never made any attempt to suggest methodologies for identifying outcomes or impact. People have tried, but there's never been a coherent single approach accepted for it. (UK Int 9)

…with the not-for-profit sector, engagement is much more challenging because the sector is so diverse. And that's where it was really helpful to have [peak bodies] involved in the process, because they had good networks, and we didn't. (NZ Int 3)

One of these representatives argued that the lack of resources in the charity sector to assimilate new regulation was a reason “to work on amelioration rather than resistance” with the regulatory body. Hence, regulatees engage with regulators as a deliberate strategic response to proposed regulation, that is, Kane's (1983) “antithesis.” The inclusion of regulatees in the regulatory bodies and subcommittees in both jurisdictions is important for starting the dialectic and forms the basis of the more partnered and less adversarial engagement (than Kane (1983) envisages) that develops later.

6.3 Repeated Formal and Informal Interactions Facilitate a Dialectic Necessary for New Governance Regulation

6.3.1 Formal Consultations

Both jurisdictions use formal public consultations to develop (and in the UK seek approval for) performance reporting regulation. These create regular opportunities for repeated interaction and allow for transparency (Amirkhanyan et al. 2017).

You can see in the latest round of consultation questions, I think, some very clear links [with] press interests… if you went through the current questions, you can almost go, “There's the headline alongside it.” (UK Int 1)

Relatedly, both jurisdictions’ regulators consulted widely, exposing (sometimes controversial) potential reporting requirements, encouraging engagement with the consultation and subsequent regulation (UK Int 9), suggesting Kane's explicit and reputed suasion (1977).

NZ's development of performance reporting regulation commenced with a broad consultation on charity regulation, reporting, and associated legislative changes. This was facilitated by ANGOA,7 included CS and the policymaker, and reached over 2000 people, receiving strong support for charities to “tell their story” (NZ Int 3). Following these activities and the legislative change, the XRB developed an ED building on the FRSB's prior Technical Practice Aid.8 Additional consultative webinars, road shows, roundtables, and similar were run jointly and separately by the XRB and CS. Due to the protracted process and the substantial changes between the first consultation and the final standard, a limited scope revised ED was reexposed for further consultation. As in the UK, the consultation and responses are publicly available. This process is resource intensive but potentially (and importantly) demonstrates management of conflicting voices, refuting suggestions of capture and vacuous legitimacy-building (Gugerty 2010; Phillips 2012).

Our interviewees gave numerous examples of where matters discussed in the consultation process impacted the resulting standard, including definitional clarity in NZ (NZ Int 2) and a reluctance to require specific measures in the UK (UK Int 9). These changes are reflected in these organizations’ publicly available meeting minutes and consultation feedback statements. Common challenges included ensuring a wide range of stakeholders engage: “generally people are quite disengaged when it comes to accounting standards” (NZ Int 8). Hence, larger organizations in NZ (NZ Int 8) and accountants in the UK (UK Int 11) dominate consultation responses, sometimes requiring specific consultation with harder-to-reach groups such as funders (UK Int 11, see also Connolly et al. 2013). Wider engagement can also be a double–edged sword: “consultation has the merits that everybody participates. It has the demerit that it can very easily not clarify but simply confuse the picture” (UK Int 5). Similarly, in NZ, there was a sense that: “it took a lot longer just because everybody has got what they think's a good idea” (NZ Int 5), with some “good ideas” beyond the boundaries of an accounting standard (NZ Int 5) and thus abandoned after discussion and negotiation.

6.3.2 Informal Dialogs

Nigel [Davies: SORP Committee Joint Chair] would pick up the phone and say, “We're thinking of saying this.” They'll speak to different people. They'll set up little accountant-, fundraiser-groups, etc. and now they understand that there are people out there who know as much about it, or more than they do, and they may want to tap into that. There's nothing wrong with that, I think that's good. (UK Int 4)

[Our NFP sector group] had a fantastic relationship with [the first CE of the XRB] …So that was a really constructive relationship that then went into, as we got more towards regulation, working with [the policymaker drafting legislation]. (NZ Int 7)

Unsurprisingly, informal dialogs are frequently based on existing relationships, especially individuals and bodies who are represented on the regulatory body or relevant subcommittees and encourage engagement with formal public consultations. In the UK, these included ICAEW, CFG, and NCVO members (UK Int 1, 6, 8, 9, 11), and ANGOA in NZ (NZ Int 3).

Positively, such conversations facilitate deeper interaction and two-way constructive discussions. They exemplify the dialectic in action and the harnessing of sector knowledge and resources (Harrow 2006; Phillips 2012; Salamon 2002). However, unlike formal consultations, questions and responses in these conversations are not necessarily a matter of public record, nor is it clear with whom such conversations take place. This could lead to perceptions of bias or undue influence by certain actors (Potoski and Prakash 2004), threatening the resulting regulation's legitimacy (Amirkhanyan et al. 2017; Baldwin 2019).

Thus, it is evident that formal public consultations facilitate the ongoing dialectic between regulators and regulatees, demonstrating participation or collaboration (Bryson et al. 2014; Young et al. 2020). Expanding the reach of these consultations has expanded the diversity of views considered (Young et al. 2020), potentially increasing the legitimacy of the regulatory process and resulting regulation. Continuing informal dialogs with various actors facilitates consultation, education, and encourages ongoing support. Regulators demonstrate moral and explicit suasion in their engagement (Kane 1977), and regulatee engagement leads to regulatory change (Kane 1983). The informal dialogs are catalysts (Bryson et al. 2014); key actors may therefore impact regulation's creation, and regulators can harness sector expertise and resource (Solomon 2010) including “buy-in” that can build support for the resulting regulation (Phillips 2012; Trubek and Trubek 2007).

6.4 Engaged Regulatees Encourage Compliance With Regulation and Best Practice Reporting

[The regulator] is becoming increasingly good at getting us, as well as other infrastructure bodies and charities, involved in the development process. I have to really give it to them that when they are developing guidance, or any consultation, we are now starting to see more and more often us being invited to the table, us getting to see drafts, and having our input into those…we're having these opportunities to meet with them face-to-face, so that when these changes do come in, we can go away and tell our members, and write blogs about it, and explain. (UK Int 3)

So, we did maybe about seven webinars this year, lunchtime ones and I think nearly all of them were on the reporting standards, yeah. And we had something like 6,000 registrants. So, we'll continue doing that kind of thing next year but [with a different] focus. (NZ Int X9)

Without exception, the reaction to [the then forthcoming performance reporting] is “this is fantastic”. And the reason it's fantastic is simplistically for most of them, the point of view is “we now get 90% of the information we need from one place”. (NZ Int 2)

Some people in the SORP responses felt we should've been firmer rather than the nudge towards outcome and impact reporting…a minority of voices saying, “No, you really needed to push that agenda harder.” But, without any established sort of methodology for it, it's very difficult to put it in the SORP. (UK Int 9)

Again, this demonstrates that repeated interactions develop a more partnered and less adversarial relationship in contrast to the adversarial engagement between regulators and regulatees envisaged by Kane. Regulatee advocacy for developed regulation exemplifies the blurred boundaries (Solomon 2010) expected in new governance. These comments may demonstrate the potential for capture and the need to build legitimacy which are central to new governance (Baldwin 2019; Gugerty 2010; Salamon 2002), but not considered in Kane's model.

6.5 Model of New Governance Regulatory Dialectic

Our in-depth case study suggests that creating charity performance regulation through new governance regulation follows Kane's stages, but with some important differences. First, compared with command and control regulation, we observe an earlier thesis stage, with the regulators proposing an ED, rather than simply issuing regulation. Antithesis from regulatees (including stakeholders not envisaged by Kane) comes through ED responses, formal public consultations, and continuing, informal dialogs. Synthesis occurs only after these interactions, with regulation's creation.

We've already indicated that we're going to do a post-implementation review…So, that will be very much going to the users and saying, “is this meeting your demands? Is this meeting your requirements?” (NZ Int 4)10

This engagement prompts regulators to begin their cycle again by engaging with subcommittees, issuing EDs and consultations, and ultimately new regulation (Kane 1983). Although NZ has taken much longer to progress through one cycle of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, the UK has been through several such cycles.

In Figure 4, we propose a model of new governance regulatory dialectics, reflecting these differences.

The new governance regulatory dialectic follows Kane's (1977, 1980, 1983) stages of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis but with important differences. Compared to Kane's regulatory dialectic (Figure 3), we represent the gradual blurring of regulator/regulateee boundaries by suggesting riders on the seesaw gradually moving toward each other (see the dashed lines in Figure 4). As these riders move closer to each other (to new positions shown by bold-edged boxes in Figure 4), oscillations continue but are less extreme: This is represented by the bold arrows in Figure 4. Thesis, antithesis, and synthesis continue to occur, but the changing relative positions reduce extreme regulator/regulatee reactions and responses. Reduced oscillation reflects the softer approaches of the regulators—whose thesis is in the form of ED and consulation, and who employ soft suasion rather than hard enforcement—and regulatees, who engage in the development of regulation and advocate for the developed regulation rather than avoid it. Regulatee lobbying from Kane's model continues, but their closeness on the hypothetical seesaw should both reduce the likelihood of regulators and regulatees moving apart and regulatees’ search and use of loopholes. When the seesaw tilts, the other party acts, because, as in Kane's model (and playparks), stationary equilibrium is virtually impossible.

Our model is illustrated in a relatively rare example of a significant conflict in the development of performance reporting regulation. As discussed previously, UK performance reporting recommendations were expanded between the 2000 and 2005 SORP. The extensive sector debate included wide-ranging suggestions of possible changes. Some grant-making charities were particularly opposed to increased reporting requirements: “they regarded themselves as private trusts, and they didn't see any requirement to report to the public” (UK Int 9).

If you look in the 2005 Regulations, you'll see there's an exemption from reporting who you give donations to, and grants to, during the lifetime of the beneficiary of a grant-making trust. That was specifically done to appease [Lords] Hodgson and Sainsbury. (UK Int 9)

Subsequently, reflecting the expectation that these will be repeated interactions within a dialectic, a conspicuous effort was made to bring influential grant-making charities into the SORP development processes. Representatives were invited to join the SORP Committee (see Section 6.2), and grant-making charities were directly targeted in the substantial consultation exercise in 2008/9 (see Section 6.3.1 and Connolly et al. 2013). Additionally, continuing, informal dialogs (UK Int 8, 9, 11) subdued grant-making charity opposition to subsequent SORPs’ performance reporting regulation (UK Int 9, 11).

This example explains the complex balancing act of new governance, where, despite soft suasion, the regulator must deal with conflicting voices, building stakeholder legitimacy (Amirkhanyan et al. 2017; Baldwin 2019). In total, our data demonstrate how the new governance regulatory dialectic is facilitated, with clear examples of the stages of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, and respective behaviors of regulators and regulatees, including the use of suasion. The example in this subsection is unusual in the regulatory dialectic literature as the regulator exclusively used soft suasion, both in the initial conflict and subsequent efforts to defuse this. Young et al. (2020) warned that new governance regulation might fail due to power imbalances, and this danger became evident in the power of grant-making charities and some of the individuals concerned. A concern might be raised that the dialectic and the achievement of synthesis are less apparent for less powerful regulatees.

In summary, we propose a model of new governance regulatory dialectics where regulators and regulatees move together rather than apart over the stages of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, with regulatee engagement and soft suasion to the fore.

7 Conclusions

This in-depth case study analyzed two jurisdictions’ regulatory reform of charity performance reporting. The similarity of the means used to create regulation is striking, particularly in the absence of command and control, market-based approaches, or self-regulation. Co-regulation develops between the accounting standards setter (FRC & SORP Committee and XRB & NZASB/NZAuASB, respectively) and the charity regulator (CCEW, later also OSCR, CCNI, CRA, and CS, respectively). Although not engaged in formal co-regulation, representation from the sector or peak bodies on regulatory bodies or subcommittees points to blurred boundaries (Solomon 2010). These regulatees/stakeholders also engage in a dialectic through formal public consultations and informal dialogs—institutional arrangements (Baldwin 2019) to assist the acceptance of regulation and perhaps reduce the sometimes-destabilizing effects of new governance regulation (Solomon 2010). Dialectic arrangements enhance cooperation, diversity, and participation as suggested by Bryson et al. (2014) and Young et al. (2020), in developing regulation and subsequently educating and encouraging regulatees to follow best practices. Nevertheless, these arrangements cannot guarantee the balancing of power between different stakeholders (as shown in the UK grant-making charities example, which contrasts to the likely experience of less powerful regulatees).

The role of stakeholder networks is fundamental to new governance processes (Salamon 2002; Solomon 2010; Young et al. 2020). The regulator-regulatee dialectical relationship evolves regulation through repeated thesis and antithesis interactions, as our model describes. These continual adaptations (which Kane (1981) describes as a seesaw) have extended the length of NZ's standard-setting process (6 and 1/2 years from the XRB's formation to the standard's issuance and then 6 years until the effective date) and led to iterative changes in the UK over a longer period. This exemplifies the concern of Young et al. (2020) that new governance approaches are most concerned with process rather than outcomes and hence require significant time investments. The mature UK context shows that change is based on past interactions, with more stakeholders represented in regulatory bodies and subcommittees, continued formal public consultations, and the deepening of informal dialogs. Kane (1988) suggests that regulators’ and regulatees’ positions and problems arise from the history of their interactions. Our amended seesaw model (Figure 4) suggests that this history can result in fewer problems as regulators and regulatees gradually move toward one another.

Here, regulators engage primarily using “soft” approaches rather than “hard” penalties or enforcement. Moral suasion (Kane 1977) underpins the framing of the SORP's performance reporting as recommendations, and the ongoing work to build a consensus to support this, particularly using interested and expert representatives (the stakeholder network (Salamon 2002)). As performance reporting regulation matures, we also observe examples of explicit suasion—where the regulator formally encourages compliance. Examples include joint roadshows with sector bodies in NZ and UK SORP committee engagement with the CFG, ICAEW, and more recently NCVO, initially to consult their members, then using moral and explicit suasion (Kane 1977) to “sell” new regulation to their members/affected charities. Similarly, the SORP Committee and XRB populate working groups with sector representatives to both seek input and broadcast their message via seminars, conferences, and so forth. This is particularly important, to emphasize the need to report well rather than merely to report (a hallmark of new governance-type regulation) if the principal-agent issue of information asymmetry is to be overcome. In both jurisdictions, the threat of heavier regulation, and more prescription of what to report (a more command and control type approach) remains as the “big stick” to drive engagement with this process (Kane's (1977) reputed suasion).

Regulatees also employ softer tools of resistance under new governance than with command and control-style regulation. Key stakeholders influence new regulation primarily by lobbying for change through the described mechanisms; there is little evidence of forceful opposition or moving away from the regulator (virtually impossible in the charity space). Quiet avoidance remains an option, especially in the UK context where the reports are not audited, but also in NZ where it is potentially possible to meet the requirements yet provide comparatively meaningless information. Although hard evidence of the scale of such avoidance is lacking in both jurisdictions, those engaged in regulation are alert to anecdotal evidence of avoidance or potential for avoidance in developing recommendations/requirements: for example, in decisions related to requiring specific metrics in the UK, or avoidance of certain terms in NZ. These approaches should increase transparency in the public interest.

Our extension of Kane's regulatory dialectics suggests new governance regulatory dialectics are less adversarial, illustrated in Figure 4 by the reduced oscillation of the seesaw as riders move closer together. Rather than one party creating economic regulation, and forceful opposition and resistance by (only) self-interested others, the mechanisms used to facilitate the new governance regulatory dialectic appear to act as buffers ameliorating opposition, resulting in a smoother, less adversarial, and more partnered process. This may be due to perception of the public good (Bryson et al. 2014; Hertog 1999; Radaelli and Meuwese 2009) or of performance reporting as an important means of charity legitimation (Dhanani and Connolly 2012; Pape et al. 2020). Some may argue that performance reporting also has a lower personal or organizational cost than other sectors’ regulation (e.g., banking). Nevertheless, we suggest the new governance approach reduced the contentiousness of performance reporting regulation by developing generally acceptable requirements and persuading regulatees of the benefits of compliance and good practice. A third perspective might suggest regulatory capture (Hertog 1999): Some UK interviewees indicated that they believed the SORP to be deliberately “mild” on performance reporting, perhaps because regulatees involved in its development have sought an easier path. This also raises the issues of who is engaged in, or excluded from, regulatory bodies and subcommittees, the difficulties of engaging regulatees in consultations, and the potential for informal dialogs to result in perceptions of undue influence on the process. These concerns have been expressed about new governance regulation more broadly (Potoski and Prakash 2004; Young et al. 2020).

This article develops a model of new governance regulatory dialectics, contributing to the regulatory dialectics’ literature, as well as nonprofit/charity regulation research, both areas described as under-theorized (Bryson et al. 2015; O'Toole 2014). This evidence and model can inform those charged with regulating charities, government policymakers, those who are regulated, and those who would seek to influence regulation. As well as encouraging regulators to engage in a networked way and evidencing the advantages of engaging with soft suasion methods to ensure compliance, our findings show the benefits for regulatees (practitioners) of engaging actively in regulatory processes, for example, in seeking representation on regulatory bodies or contributing to formal consultations or informal dialogs.

As with all research, this is not without limitations, specifically as the nature of new governance with a wide range of involved parties creates a challenge in identifying and engaging with a representative range of knowledgeable actors, and those excluded from the process may have also been excluded from our research. Additionally, we acknowledge limitations associated with our methodology, including challenges of memory, risk of error or omission, and the subjective analysis of a substantial amount of evidence, which we have tried to mitigate as discussed earlier. Finally, the UK and NZ are at different stages on the regulatory cycle, and although this analysis is contextually limited, this in-depth case provides an opportunity for analytical generalization and opens areas for further research on the impact of regulatory reform on reporting practices. Modeling new governance regulatory dialectics appears to provide a way forward for practitioners, but also for theorizing and researching charity regulation which should assist its further development in the public interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for feedback from colleagues and participants in seminars at the University of Edinburgh and Queen's University Belfast and the EIASM Challenges of Managing the Third Sector Conference, Aberdeen, 2023.

Ethics Statement

This research has been conducted in line with ethical approval granted in our respective institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Appendix

Interviewees and Guiding Questions

| Assigned number UK | Background | Date | Minutes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewee 1 | Professional Institute and Practitioner Sector Body, 2015 and current SORP Committees, Non-accountant | June 2017 | 79:17 |

| Interviewee 2 | Sector Body, Current SORP Committee, Non-Accountant | June 2017 | 86:52 |

| Interviewee 3 | Sector Body, Non-Accountant | June 2017 | 59:14 |

| Interviewee 4 | Practitioner, Practitioner Sector Body, 1995, 2000, 2005 and current SORP Committees, Accountant | June 2017 | 51:52 |

| Interviewee 5 | Practitioner, Regulator, 1995 SORP Committee, Accountant | June 2017 | 98:12 |

| Interviewee 6 | Practitioner, Practitioner Sector Body, Accountant | August 2017 | 49:00 |

| Interviewee 7 | Standard setter, 2015 and current SORP Committees, Accountant | July 2017 | 26:10 |

| Interviewee 8 | Regulator, 2015 and current SORP Committee, Accountant | July 2017 | 97:55 |

| Interviewee 9 | Regulator, 2000, 2005 and 2015 SORP Committee, Accountant | July 2017 | 44:16 |

| Interviewee 10 | Practitioner, Civil Servant in Government Department, Regulator, 1995 SORP Committee, Accountant | June 2017 | 92:19 |

| Interview 11 | Regulator, 2005, 2015 and current SORP Committees, Accountant | June 2017 | 73:44 |

| Assigned number NZ | Background | ||

| Interviewee 1 | Treasury official, Standard Setter (locally and internationally), Accountant | December 2017 | 75:20 |

| Interviewee 2 | Audit Partner, Mid-Tier Firm, Standard Setter, Accountant, Member (Trans-Tasman) profession's charities sector advisory body | January 2018 | 60:10 |

| Interviewee 3 | Policymaker in Government Department, Accountant | December 2017 | 52:40 |

| Interviewee 4 | Standard Setter staff, Past President of Professional Body, International Office Holder, Accountant | December 2017 | 63:29 |

| Interviewee 5 | Standard Setter staff, Accountant | January 2018 | 77:48 |

| Interviewee 6 | Standard Setter staff, Accountant | January 2018 | 77:48 |

| Interviewee 7 | Sector Body, Non-Accountant | January 2018 | 62:12 |

| Interviewee 8 | Regulator, Accountant, Member (Trans-Tasman) profession's charities sector advisory body | December 2017 | 43:45 |

- – Thinking about the process through which requirements for performance reporting developed (a) what stakeholder interests were involved, (b) how were these interests mediated?

- – How did specific changes come about and how were you (or your organization) involved?

- – What change did you observe in charities’ performance reporting after the change/s?

- – Are further changes needed and what would be needed to be palatable for stakeholders?

- – How has this process been similar to or different from other accounting standard changes?

- – (NZ only—what was the impact of the requirement for assurance on this process?)

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.