Differential efficacy of remote ischaemic conditioning in anterior versus posterior circulation stroke: A prespecified secondary analysis of the RICAMIS trial

Xin-Yu Shen and Ying-Jie Dai contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Background and Purpose

The benefit of remote ischaemic conditioning (RIC) in acute moderate ischaemic stroke has been demonstrated by the Remote Ischaemic Conditioning for Acute Moderate Ischaemic Stroke (RICAMIS) study. This prespecified exploratory analysis aimed to determine whether there was a difference of RIC efficacy in anterior versus posterior circulation stroke based on RICAMIS data.

Methods

In this analysis, eligible patients presenting within 48 h of stroke onset were divided into two groups: anterior circulation stroke (ACS) and posterior circulation stroke (PCS) groups. The primary endpoint was an excellent functional outcome, defined as a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score 0–1 at 90 days.

Results

In all, 1013 patients were included in the final analysis, including 642 with ACS and 371 with PCS. Compared with the control group, RIC was significantly associated with an increased proportion of mRS scores 0–1 within 90 days in the PCS group (unadjusted odds ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.0–2.4, p = 0.04; adjusted odds ratio 2.0, 95% confidence interval 1.2–3.3, p = 0.005), but not in the ACS group (p = 0.29). Similar results were found regarding secondary outcomes including mRS score 0–2 at 90 days, mRS distribution at 90 days and change in National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score at day 12 from baseline. However, there was no significant interaction effect between stroke location and intervention on the primary outcome (pinteraction = 0.21).

Conclusion

Amongst patients with acute PCS who are not candidates for reperfusion treatment, RIC may be associated with a higher probability of improved functional outcomes. These findings need to be validated in prospective trials.

INTRODUCTION

Reperfusion treatments such as intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular thrombectomy have been standard treatments for acute ischaemic stroke (AIS); however, only a small proportion of patients can receive them due to the strict time window as well as the requirement of skilled operators and equipment [1-3]. Neuroprotective strategies to improve the outcomes of AIS patients have been an active area of research [4]. Since the report of ischaemic preconditioning in 1986 [5], remote ischaemic conditioning (RIC) was found to exert a neuroprotective role by reducing cerebral infarction and improving neurological outcomes in preclinical and clinical studies [6, 7]. However, the benefit of RIC in AIS was controversial [8, 9]. Importantly, the RICAMIS (Remote Ischaemic Conditioning for Acute Moderate Ischaemic Stroke) study, a large-scale, multicentre, randomized trial, showed that RIC therapy significantly increased the possibility of good neurological function at 90 days compared to standard stroke treatment [10], which provided robust evidence for neuroprotection of RIC in stroke, although the finding was not confirmed by the recent RESIST trial [11].

It is well known that there are differences between anterior circulation stroke (ACS) and posterior circulation stroke (PCS), including differences in anatomical structure, collateral circulation, blood supply, clinical symptoms, signs and prognosis, ischaemic tolerance duration, and treatment effects [12-15]. In this context, it was hypothesized that there may be a difference in the efficacy of RIC in patients with anterior versus posterior circulation stroke, which has not been investigated. In this prespecified secondary analysis of RICAMIS [10, 16], this issue was explored.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This study was a secondary analysis of the RICAMIS study, which was a multicentre, open-label, blinded endpoint, randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of 2 weeks of RIC in patients with acute moderate ischaemic stroke presenting within 48 h of symptom onset. Details of the design and procedures of RICAMIS have been published [17]. The key inclusion criteria of the RICAMIS study were patients aged ≥18 years who had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 6–16 on admission, who had been functioning independently in the community before a stroke (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score 0–1; range 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]), and who could be randomized within 48 h after onset of stroke symptoms (the time the patient was last known to be well). The key exclusion criteria included patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular therapy, had uncontrolled severe hypertension, contraindications to RIC or had an aetiology of cardiogenic embolism. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned 1:1 without stratification to receive treatment with either RIC in addition to guideline-recommended treatment (such as antiplatelets, anticoagulants or statins) or only guideline-recommended treatment. In this analysis, patients who did not complete the prespecified intervention were excluded. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by appropriate regulatory and ethical authorities at the ethics committee, and all patients or their legally authorized representatives signed a written informed consent before entering the study. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03740971).

Procedures

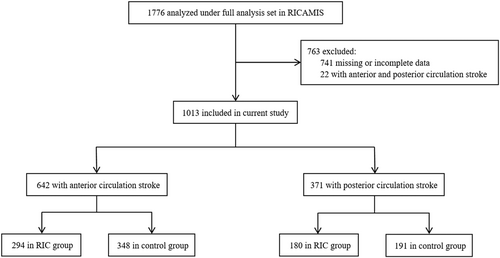

Based on clinical symptom and neuroimaging data, eligible patients were divided into two groups: an ACS group with culprit vessel located in the internal carotid, middle or anterior cerebral artery, and a PCS group with culprit vessel in the vertebral, basilar or posterior cerebral artery. Patients with lacunar cerebral infarction who did not show any corresponding ischaemic lesions and those who could not be clearly grouped were excluded (Figure 1). The RIC treatment was initiated within 48 h of symptom onset, using a pneumatic electronic automatic control device to render the brachial artery ischaemic by cuff inflation (200 mmHg for 5 min) and deflation (5 min) for five cycles, twice daily for 10 to 14 days [10]. Neurological status was measured using the NIHSS score at admission and at 7 and 12 days after randomization, and follow-up data were collected at 90 days after randomization.

Study outcomes

In this secondary analysis of the RICAMIS trial, the outcomes paralleled the primary study [10]. The primary outcome was excellent functional outcome at 90 days, defined as an mRS score of 0–1. The secondary outcomes were favourable functional outcome at 90 days, defined as an mRS score of 0–2; a shift in measure of function according to the distribution on the ordinal mRS at 90 days; occurrence of early neurological deterioration compared with baseline at 7 days, defined as more than a 2-point increase in NIHSS, but not as a result of cerebral haemorrhage; occurrence of stroke-associated pneumonia at 12 days; change in NIHSS compared with baseline at 12 days; time from randomization to occurrence of stroke or other vascular events at 90 days; and occurrence of death within 90 days. The 90-day outcomes were adjudicated by a certified staff member from each centre who was unaware of the randomized treatment assignment. Baseline and follow-up NIHSS were performed by the same neurologist who was not blinded to the assigned treatment.

Statistical Analysis

The current study was based on patients in the full analysis set of the RICAMIS study. For the baseline characteristics, the continuous variables were tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk). For normally distributed continuous data, mean ± SD was presented and Student's t tests were used to test the significance between the two groups. Data with skewed distribution were described as median and interquartile range (IQR), and comparisons between the two groups were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U rank sum test.

Binary logistic regression analyses were performed for the primary and secondary outcomes of favourable functional outcome at 90 days, the occurrence of early neurological deterioration, stroke-associated pneumonia and other vascular events. The treatment effects for the above outcomes are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The 90-day mRS score was compared using ordinal logistic regression. Change in NIHSS between admission and at 12 days was compared using a generalized linear model, and risk differences between RIC and control groups with their 95% CIs were derived. Occurrences of all-cause mortality at 90 days were compared using the Cox regression model. The primary analyses of primary and secondary outcomes were unadjusted. Covariate adjusted analyses were performed for all outcomes, adjusting for the prespecified prognostic factors used in the primary study.

Interactions of treatment effects on primary outcomes were assessed between the ACS and PCS subgroups. The assessments of the two subgroups and the effect of treatment on primary outcomes were conducted with a generalized linear model, ordinal regression analysis or Cox regression model with the treatment groups, ACS and PCS subgroups and their interaction term as independent variables, and the pint values were presented for the interaction term.

All analyses presented were exploratory, and all p values were nominal. Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 26.0, IBM) and R software (version 4.3.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

Amongst 1776 full analysis set patients in the RICAMIS trial, a total of 1013 patients were included in this secondary analysis including 642 in the ACS group and 371 in the PCS group (Figure 1). In the ACS group, 294 (45.8%) patients received RIC, and 180 (48.5%) patients received RIC in the PCS group. Table 1 shows the detailed baseline characteristics of the RIC and control groups across the ACS and PCS groups. In the ACS group, the baseline NIHSS score was higher in the RIC group compared with the control group (median [IQR], 7 [6–10] vs. 7 [6–9], p = 0.05). Baseline characteristics between the RIC and control groups were otherwise balanced across the ACS and PCS subgroups.

| ACS | PCS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remote ischaemic conditioning (N = 294) | Control (N = 348) | p value | Remote ischaemic conditioning (N = 180) | Control (N = 191) | p value | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 65 (10.5) | 66 (9.8) | 0.41 | 66 (10.2) | 65 (9.7) | 0.32 |

| Sex (F) | 96 (32.7) | 111 (31.9) | 0.84 | 65 (36.1) | 72 (37.7) | 0.75 |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR)a | 24.22 (22.49–26.10) | 24.03 (22.44–25.89) | 0.37 | 24.22 (22.86–26.12) | 24.26 (22.54–26.70) | 0.43 |

| Current smoker | 100 (34.0) | 95 (27.3) | 0.11 | 54 (30.0) | 53 (27.7) | 0.87 |

| Current drinkerb | 59 (20.1) | 51 (14.7) | 0.22 | 32 (17.8) | 19 (9.9) | 0.23 |

| Comorbiditiesc | ||||||

| Hypertension | 180 (61.2) | 203 (58.3) | 0.54 | 109 (60.6) | 122 (63.9) | 0.33 |

| Diabetes | 75 (25.5) | 80 (23.0) | 0.75 | 47 (26.1) | 55 (28.8) | 0.32 |

| Previous stroked | 79 (26.9) | 93 (26.7) | 0.66 | 55 (30.6) | 55 (28.8) | 0.93 |

| Previous TIA | 5 (1.7) | 3 (0.9) | 0.42 | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.1) | 0.44 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 10 (3.4) | 4 (1.1) | 0.07 | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.6) | 0.78 |

| Cardiac disease | 4 (1.4) | 7 (2.0) | 0.81 | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.1) | 0.59 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.46 | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.0) | 1.00 |

| Blood pressure at randomization, mmHg, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Systolic | 150 (140–160) | 150 (140–165) | 0.32 | 150 (140–160) | 150 (140–160) | 0.78 |

| Diastolic | 90 (80–97) | 90 (80–100) | 0.15 | 90 (80–95) | 90 (80–95) | 0.85 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/L, median (IQR) | 6.31 (5.42–9.10) | 6.74 (5.48–10.37) | 0.21 | 6.50 (5.50–10.11) | 6.80 (5.50–10.80) | 0.35 |

| NIHSS score at baseline, median (IQR)e | 7 (6–10) | 7 (6–9) | 0.05 | 7 (6–9) | 7 (6–9) | 0.93 |

| Estimated premorbid function (mRS score)f | ||||||

| No symptoms (score, 0) | 231 (78.6) | 277 (79.6) | 0.75 | 145 (80.6) | 143 (74.9) | 0.19 |

| Symptoms without any disability (score, 1) | 63 (21.4) | 71 (20.4) | 35 (19.4) | 48 (25.1) | ||

| Time from onset to RIC, hours, median (IQR) | 25 (12–35) | 25 (14–36) | 0.36 | 27 (15–39) | 25 (13–37) | 0.47 |

| Degree of responsible vessel stenosis | ||||||

| Mild (<50%) | 122 (41.5) | 136 (39.1) | 0.80 | 71 (39.4) | 69 (36.1) | 0.44 |

| Moderate (50%–69%) | 105 (35.7) | 132 (37.9) | 80 (44.4) | 97 (50.8) | ||

| Severe (70%–99%) | 67 (22.8) | 80 (23.0) | 29 (16.1) | 25 (13.1) | ||

| Presumed stroke causeg | ||||||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 136 (46.3) | 185 (53.2) | 0.37 | 90 (50.0) | 99 (51.8) | 0.12 |

| Cardioembolic | 5 (1.7) | 5 (1.4) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.6) | ||

| Small artery occlusion | 45 (15.3) | 55 (15.8) | 24 (13.3) | 37 (19.4) | ||

| Other | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0) | ||

| Undetermined | 105 (35.7) | 101 (29.0) | 59 (32.8) | 52 (27.2) | ||

- Note: The data are shown with median (interquartile range) or number (percentage).

- Abbreviations: ACS, anterior circulation stroke; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PCS, posterior circulation stroke; RIC, remote ischaemic conditioning; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

- a Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared. Data missing for three participants for BMI.

- b Defined as consuming alcohol at least once a week within 1 year prior to the onset of the disease.

- c The comorbidities were based on the patient or family report.

- d Previous stroke included ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke.

- e NIHSS scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurological deficit.

- f Scores on the mRS of functional disability range from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death).

- g The presumed stroke cause was classified according to the Trial of ORG10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) using clinical findings, brain imaging and laboratory test results. Other causes included nonatherosclerotic vasculopathies, hypercoagulable states and haematological disorder.

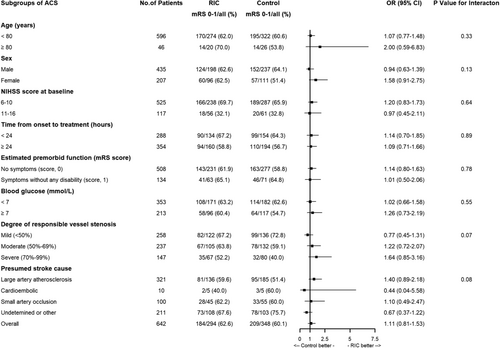

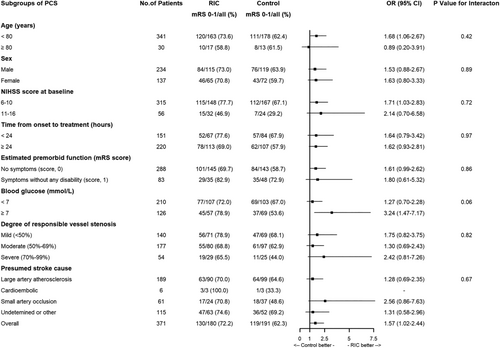

Table 2 presents the association of the RIC versus control groups with their clinical outcomes. For the primary outcome, compared with the control group, RIC was significantly associated with an increased proportion of mRS scores of 0–1 within 90 days in the PCS group (unadjusted OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0–2.4, p = 0.04; adjusted OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.3, p = 0.005), but not in the ACS group (unadjusted OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.8–1.5, p = 0.51; adjusted OR 1.2, 95% CI 0.9–1.7, p = 0.29). Similar results were found with regard to some secondary outcomes including mRS score of 0–2 within 90 days, mRS distribution at 90 days and changes in NIHSS score at day 12 from baseline (Table 2, Figure 2). Other secondary outcomes including early neurological deterioration compared with baseline at 7 days, stroke-associated pneumonia, occurrence of stroke or other vascular events at 90 days, and occurrence of death due to any cause within 90 days were not different amongst the RIC and control groups across the ACS and PCS subgroups (Table 2).

| Outcomes | Subgroupsa | Number (%) of events or median difference | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | pint value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remote ischaemic conditioning | Control | Treatment difference (95% CI) | p value | Treatment difference (95% CI) | p value | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| mRS score of 0–1 at 90 daysc | ACS | 184/294 (62.6) | 209/348 (60.1) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.5) | 0.51 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7) | 0.29 | 0.21 |

| PCS | 130/180 (72.2) | 119/191 (62.3) | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.4) | 0.04 | 2.0 (1.2 to 3.3) | 0.005 | ||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| mRS score of 0–2 at 90 days | ACS | 224/294 (76.2) | 257/348 (73.9) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.6) | 0.50 | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | 0.27 | 0.40 |

| PCS | 149/180 (82.8) | 146/191 (76.4) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.5) | 0.13 | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.5) | 0.02 | ||

| mRS distribution at 90 daysd | ACS | NA | NA | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 0.27 | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| PCS | NA | NA | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.1) | 0.04 | 1.7 (1.2 to 2.5) | 0.007 | ||

| Early neurological deterioration within 7 dayse | ACS | 21/270 (7.8) | 28/346 (8.1) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.7) | 0.89 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7) | 0.84 | 0.99 |

| PCS | 7/172 (4.1) | 8/190 (4.2) | 1.0 (0.3 to 2.7) | 0.95 | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.5) | 0.77 | ||

| Change in NIHSS score at day 12 from baselinef | ACS | −4 (−5 to −2) | −4 (−6 to −2) | 0.2 (−0.4 to 0.7) | 0.51 | 0.1 (−0.4 to 0.7) | 0.62 | 0.17 |

| PCS | −4 (−6 to −3) | −4 (−5 to −2) | 0.8 (0.2 to 1.4) | 0.01 | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.4) | 0.003 | ||

| Stroke-associated pneumonia within 12 daysg | ACS | 6/294 (2.0) | 7/348 (2.0) | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.1) | 0.98 | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.2) | 0.95 | 0.53 |

| PCS | 2/180 (1.1) | 4/191 (2.1) | 0.5 (0.1 to 2.9) | 0.46 | 0.4 (0.1 to 2.3) | 0.29 | ||

| Stroke or other vascular events within 90 days | ACS | 4/294 (1.4) | 3/345 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.3 to 7.1) | 0.56 | 1.7 (0.4 to 7.6) | 0.51 | 0.998 |

| PCS | 1/180 (0.6) | 0/191 (0) | NA | 0.996 | NA | 0.995 | ||

| All-cause death at 90 daysh | ACS | 2/294 (0.7) | 4/348 (1.1) | 0.6 (0.1 to 3.2) | 0.54 | 0.5 (0.1 to 3.1) | 0.47 | 0.998 |

| PCS | 1/180 (0.6) | 0/191 (0) | NA | 0.61 | NA | 0.57 | ||

- Note: pint value means the p value for interaction.

- Abbreviations: ACS, anterior circulation stroke; CI, confidence interval; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; N/A, not applicable; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PCS, posterior circulation stroke.

- a There were 642 patients in the ACS subgroup and 371 patients in the PCS subgroup.

- b Adjusted for key prognostic covariates (age, sex, premorbid function [mRS score 0 or 1]), NIHSS score at randomization, history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack, and time from the onset of symptoms to remote ischaemic conditioning.

- c mRS scores range from 0 to 6: 0, no symptoms; 1, symptoms without clinically significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; 6, death. Calculated using a generalized linear model and presented as risk difference.

- d Calculated using ordinal regression analysis and presented as odds ratio.

- e Early neurological deterioration was defined as an increase between baseline and 7 days of 2 on the NIHSS score, but not a result of cerebral haemorrhage. Data missing for 35 participants for NIHSS (32 in the remote ischaemic conditioning group and three in the control group).

- f NIHSS scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater stroke severity. Analysed using the generalized linear model and presented as geometric mean ratio.

- g Stroke-associated pneumonia was defined according to the recommendation from the pneumonia in stroke consensus group.

- h Calculated with the Cox regression model.

In addition, there was no interaction effect of intervention (RIC or control) according to ACS and PCS for primary and secondary outcomes in relation to age, sex, NIHSS score at baseline, time from onset to RIC, blood glucose, degree of responsible vessel stenosis and presumed stroke cause (Table 2, Figures 3 and 4). However, there was an interesting finding that patients with PCS had a higher excellent functional outcome in the high blood glucose subgroup compared to patients with ACS (Figures 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

In this prespecified secondary analysis, RIC was significantly associated with an increased probability of better functional outcomes in patients with PCS, which was not identified in the subgroup of patients with ACS, although stroke location (ACS vs. PCS) was not found to affect the overall efficacy of RIC.

The differences between ACS and PCS have been widely reported [14, 15]. Prior studies suggested that a longer time window of clinical benefit of intravenous thrombolysis and endovascular treatment was found in patients with PCS [18-21]. The extended treatment effect could be attributed to longer duration of salvage of brain tissue in patients with PCS compared with ACS, due to a higher proportion of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis aetiology, better collateral circulation and greater resilience to ischaemia in the brainstem [18, 22-24]. The longer duration of salvageable brain tissue in PCS could be attributed to the current finding that RIC produced more benefit in patients with PCS versus ACS, since RIC was reported to rescue ischaemic penumbra in prior studies [6, 25, 26]. Furthermore, it was found that RIC improved early as well as long-term functional outcomes, which was reflected by a significantly increased proportion of excellent functional outcome, favourable functional outcome as well as decreased NIHSS at 12 days in patients with PCS versus ACS. Given the potentially longer duration of salvage of brain tissue in PCS, RIC may partially rescue the ischaemic penumbra when initiating RIC within 48 h of stroke onset, thereby improving early neurological function in patients with PCS. This salvaged penumbra as well as neurorestorative effect [27] induced by RIC could have a positive impact on long-term functional outcomes, which may explain the present findings. Whilst baseline characteristics were largely similar between the RIC and control groups, the baseline NIHSS was slightly higher in the ACS RIC group, but not statistically different, which may have diminished the treatment effect of RIC in the ACS versus PCS groups. Unexpectedly, it was found that PCS patients with high blood glucose levels in the study had better functional outcomes than those with ACS. This may be a chance result due to small sample size, which deserves to be investigated.

It is unknown whether there exists a specific mechanism underlying RIC to ACS versus PCS. It is speculated that RIC should exert common mechanisms in ACS and PCS, which may involve anti-inflammatory responses, anti-oxidative stress, angioneogenesis etc. [28-31]. Given the differences in these two types of strokes' pathophysiological processes affecting different brain regions as well as differences in anatomical structure, collateral circulation and blood supply [12-15, 21], there may be a difference in the effect of the RIC. For example, previous animal studies have shown that the vertebrobasilar vessels have a greater capacity to mechanically vasodilate and vasoconstrict compared to carotid-based vasculature, suggesting greater dynamic autoregulatory ability [32], which may be partially attributed to the benefit of RIC in PCS. The differential mechanisms underlying RIC in ACS versus PCS warrant further investigation.

The main strength of this study is that, to our knowledge, this is the first report that RIC may be more likely to achieve a better functional outcome at 90 days in patients with PCS compared with patients with ACS, based on a large-scale, randomized, multicentre study. However, some limitations are acknowledged. The main limitation was the sample imbalance between the ACS and PCS groups and the relatively small sample size of patients with PCS, which may have reduced the statistical power of the study and possibility of a type I error. The second limitation was the lack of sham intervention in the control group and the lack of blinding of adjudicators to assess secondary outcomes for NIHSS, but the primary outcome was evaluated blindly. Third, the generalizability of the findings should be confirmed in other cohorts, especially in non-Chinese populations given the higher proportion of intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis in the Chinese population. Finally, due to the exploratory nature of this secondary analysis, the current findings should be interpreted cautiously.

In conclusion, this prespecified secondary analysis of the RICAMIS study suggests that RIC may be associated with more excellent outcomes and less disability in patients with PCS who are not suitable for intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular thrombectomy, compared with patients with ACS. These findings need to be validated in prospective trials.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Xin-Yu Shen: Data curation; formal analysis; writing – original draft. Ying-Jie Dai: Data curation; formal analysis; writing – original draft. Thanh N. Nguyen: Writing – review and editing. Hui-Sheng Chen: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; writing – review and editing; project administration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Project Plan of Liaoning Province (2019JH2/10300027). The funders of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. All the participating hospitals and clinician investigators are thanked.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Nothing to report.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.