Presumed aetiologies and clinical outcomes of non-lesional late-onset epilepsy

Abstract

Background and purpose

Our objective was to define phenotypes of non-lesional late-onset epilepsy (NLLOE) depending on its presumed aetiology and to determine their seizure and cognitive outcomes at 12 months.

Methods

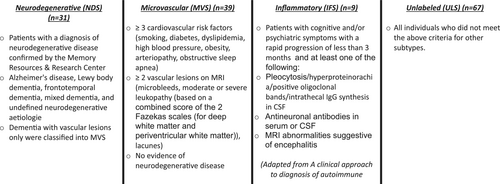

In all, 146 newly diagnosed NLLOE patients, >50 years old, were prospectively included and categorized by four presumed aetiological subtypes: neurodegenerative subtype (patients with a diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease) (n = 31), microvascular subtype (patients with three or more cardiovascular risk factors and two or more vascular lesions on MRI) (n = 39), inflammatory subtype (patient meeting international criteria for encephalitis) (n = 9) and unlabelled subtype (all individuals who did not meet the criteria for other subtypes) (n = 67). Cognitive outcome was determined by comparing for each patient the proportion of preserved/altered scores between initial and second neuropsychological assessment.

Results

The neurodegenerative subtype had the most severe cognitive profile at diagnosis with cognitive complaint dating back several years. The microvascular subtype was mainly evaluated through the neurovascular emergency pathway. Their seizures were characterized by transient phasic disorders. Inflammatory subtype patients were the youngest. They presented an acute epilepsy onset with high rate of focal status epilepticus. The unlabelled subtype presented fewer comorbidities with fewer lesions on brain imaging. The neurodegenerative subtype had the worst seizure and cognitive outcomes. In other groups, seizure control was good under antiseizure medication (94.7% seizure-free) and cognitive performance was stabilized or even improved.

Conclusion

This new characterization of NLLOE phenotypes raises questions regarding the current International League Against Epilepsy aetiological classification which does not individualize neurodegenerative and microvascular aetiology per se.

INTRODUCTION

As the world's population ages, the prevalence of epilepsy in older people is set to rise substantially worldwide [1]. The incidence of epilepsy is at least two times higher in patients over 50 years old than in younger people, with an estimated 25 cases per 1000 person-years [2].

In the literature, cerebrovascular disease (20%–40%), dementia (7%–20%), head trauma (2%–10%), brain tumours (5%–15%) and inflammatory disorders (5%–9%) are the most common aetiologies for the onset of epilepsy in older people [3, 4]. Nevertheless, in 30%–50% of cases the aetiology is unclear. This is particularly related to non-lesional late-onset epilepsy (NLLOE), which accounts for 25%–53% of late-onset focal epilepsies [3]. The various clinical and paraclinical phenotypes of NLLOE are not yet well defined.

These phenotypes may depend on the specific epilepsy aetiologies of older adults. It is remarkable how recent is the consideration of aetiology in the classification of epilepsy. For the first time in 2017 [5], the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) commission incorporated aetiologies in its new classification, emphasizing the need to consider aetiology at each step of diagnosis as it often carries significant treatment implications and prognosis [6]. Nevertheless, this aetiological classification remains limited and does not consider the characteristics of the older subject, which differ from those of the young population. The older person is intrinsically different because of the comorbidities and age-related risk of neurodegenerative disease.

The purpose of this study was to identify presumed aetiological phenotypes of a cohort of older patients with NLLOE occurring after 50 years of age and also to suggest that a detailed consideration of aetiology should be an important dimension of a new classification specific to older people.

The different presumed aetiological subtypes were defined after an extended systematic evaluation (electroencephalography [EEG], neuropsychological assessment [NP], computed tomography [CT] scan or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography [FDG-PET] and cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] profile analysis). Systematic patient follow-up was also carried out, and short-term (12 months) seizure and cognitive outcomes under antiseizure medication (ASM) were identified to determine prognoses for different presumed aetiological subgroups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Consecutive patients with age at epilepsy onset ≥50 years who were newly diagnosed with NLLOE by an epileptologist at Nancy University Hospital between June 2017 and January 2021 were included.

Patients were excluded (i) who could not be followed in our centre; (ii) with lesional epilepsy (brain tumour, stroke, head trauma); (iii) with acute symptomatic seizures (acute brain lesion on imaging, drug use, abnormal ionogram); (iv) with a history of epilepsy before 50 years of age; (v) with alcohol or drug abuse.

First evaluation

Once the NLLOE diagnosis had been made, all patients were offered an extended systematic evaluation (first NP [NP1], CT scan or MRI, FDG-PET). CSF profile analysis was performed if NP1 confirmed anterograde memory disorders or cognitive impairment with loss of autonomy or if an inflammatory cause was suspected.

- Microvascular subtype (MVS): patients with three or more of seven cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, high blood pressure, obesity, arteriopathy (peripheral artery disease or coronary artery disease), obstructive sleep apnoea) and two or more vascular lesions on MRI (microbleeds, moderate or severe leukopathy [based on a combined score of the two Fazekas scales, for deep white matter and periventricular white matter, graded from normal–mild–moderate–severe [7]], lacunes) and no evidence of neurodegenerative disease (adapted from atherosclerosis, small-vessel disease, cardiac source, other cause, dissection [ASCOD] phenotyping of patients with small-vessel disease [8]).

- Neurodegenerative subtype (NDS): patients with a diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease (Alzheimer's disease, AD [9], Lewy body dementia, LBD [10], frontotemporal dementia, FTD [11], mixed dementia and undefined neurodegenerative aetiologies) confirmed by the Memory Resources and Research Centre. Patients with isolated vascular dementia (dementia with vascular lesions only) were classified as MVS [8].

- Inflammatory subtype (IFS): patients with cognitive and/or psychiatric symptoms with a rapid progression of less than 3 months and at least one of the following: antineuronal antibodies in serum or CSF, CSF pleocytosis or hyperproteinorachia or positive oligoclonal bands or intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) synthesis in CSF, MRI suggestive of encephalitis and no evidence of other subtypes (adapted from a clinical approach to the diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis [12]).

- Unlabelled subtype (ULS): all individuals who did not meet the above criteria.

Second evaluation

Non-lesional late-onset epilepsy patients were followed for 12 months and evaluated for seizure control and cognitive outcome during a second neuropsychological assessment (NP2).

- Degradation: at least one additional neuropsychological test result below the 5th percentile or 1.65 standard deviations below the mean with no improvement in any other neuropsychological test

- Improvement: at least one additional neuropsychological test result above the 5th percentile or 1.65 standard deviations above the mean with no decline in any other neuropsychological test

- Stable: patients that did not meet the criteria for any of the other outcomes

- Normalization: normalization of all neuropsychological test results

Seizure outcome was defined as seizure free if seizures were fully controlled during this 12-month period under ASM.

Data collection

For each patient, specific data were prospectively collected from medical charts and epilepsy expert evaluations: (i) general and epileptic clinical data; (ii) brain MRI or CT scan data if MRI was contraindicated (with a score of leukopathy based on a combined score of the two Fazekas scales [for deep white matter and periventricular white matter] graded from normal–mild–-moderate–severe [7] and the Scheltens score [13] performed by neuroradiologists); (iii) brain FDG-PET data; (iv) cyto-biochemical data (complete blood count, C-reactive protein, antineuronal antibodies, thyroid-stimulating hormone); (v) CSF data (cell number, proteinorachia, oligoclonal band positivity or intrathecal IgG synthesis, antineuronal antibodies, levels of tau protein, phosphorylated tau protein, Aβ42 peptide); (vi) long-term EEG data (>3 h); (vii) NP data (16-item Free and Cued Recall, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test Revised, Forward and Backward Digit Span, Trail Making Test, Stroop test, verbal fluency test, Oral Denomination 80, praxis tests, Benton Judgement of Line Orientation, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7, Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy). Cognitive impairments were defined by scores below the 5th percentile or 1.65 standard deviations below the mean. A loss of autonomy was defined by being dependent on others for activities of daily living or nursing home placement.

Statistical analyses

Comparisons between groups were performed using Fisher's exact test or χ2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. A p value of 0.05 was used to determine significant results. A Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple pairwise comparisons using a false discovery rate of 0.1 was then performed. Missing data were excluded from statistical analyses.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations and patient consents

All clinical data were collected prospectively during a routine clinical work-up. All participants or legal representatives signed a non-opposition form. Neuropsychological data extraction was approved by the Regional Ethical Standards Committee on Human Experimentation (France, CPP no. 20.07.23.36832).

RESULTS

Clinical and paraclinical features of the NLLOE population at diagnosis timing

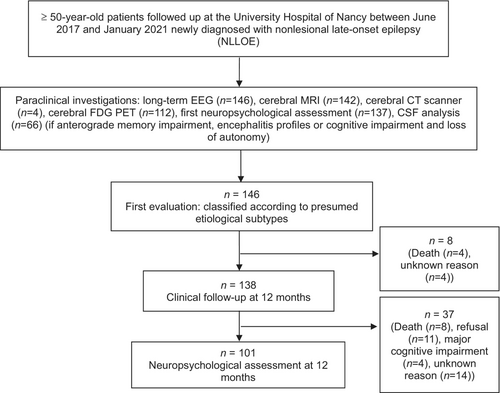

Initially 146 patients were included (Figure 2). Clinical and paraclinical features of the NLLOE population are described in Table 1. According to the ILAE classification, focal aware seizure was the most frequent (n = 66, 45.2% of all the population), followed by focal impaired awareness seizure (n = 53, 36.3%). Focal status epilepticus occurred in only 5.4% (n = 8).

| n = 146 | |

|---|---|

| Number of men/women, % (n) | 52/48 (70/76) |

| First seen through the neurovascular emergency pathway, % (n) | 34.9 (51) |

| Autoimmune comorbidities, % (n) | 18.5 (27) |

| Psychiatric disorders, % (n) | 21.2 (31) |

| Past vascular history, % (n) | 76.7 (112) |

| Initial cognitive complaint, % (n) | 32.9 (48) |

| Age at onset of epilepsy (years) (mean ± SD) | 69.3 (± 10.5) |

| Epilepsy duration (months) (mean ± SD) | 43.7 (± 37.7) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) (mean ± SD) | 70.8 (± 10) |

| Duration between seizures beginning and diagnosis (months) (mean ± SD) | 18.2 (± 33.5) |

| Duration between diagnosis and ASM initiation (days) | 61 (± 135) |

| First neuropsychological assessment, % (n = 137) | |

| Normal | 11.7 (16) |

| Cognitive impairment | 69.3 (95) |

| Cognitive impairment with loss of autonomy | 19 (26) |

| Reported ictal symptoms, % (n = 146) | |

| Arrest of activity | 36.3 (53) |

| Postictal confusion | 30.8 (45) |

| Lacunar amnesia | 13.7 (20) |

| Gestural or oroalimentary automatisms | 17.1 (25) |

| Tonic limb posturing | 4.1 (6) |

| Clonus or unilateral motor deficit | 21.9 (32) |

| Myoclonus | 1.4 (2) |

| Aphasia | 24 (35) |

| Dysarthria | 1.4 (2) |

| Sensory symptoms | 8.2 (12) |

| Vertiginous symptoms | 5.4 (8) |

| Cutaneous colour changes | 4.8 (7) |

| Visual hallucinations or illusions | 2.7 (4) |

| Auditive hallucinations or illusions | 1.4 (2) |

| Olfactory or gustatory hallucinations or illusions | 4.1 (6) |

| ‘Déjà vu’ feeling | 2.1 (3) |

| Hot raise feeling | 7.5 (11) |

| Epigastric raise feeling | 4.1 (6) |

| Headache | 3.4 (5) |

| Long-term EEG features, % (n = 146) | |

| Sporadic paroxysmal discharges | 74.7 (113) |

| Spikes, polyspikes ± slow waves | 68.5 (100) |

| Sharp waves | 51.4 (75) |

| Generalized pattern | 0.7 (1) |

| Lateralized unilateral pattern | |

| Temporal or frontotemporal patterna | 68.5 (90) |

| Extra-temporal patterna | 8.2 (10) |

| Bilateral independent pattern | 12.3 (18) |

| Temporal or frontotemporal patterna | 68.5 (16) |

| Extra-temporal patterna | 8.2 (2) |

| Focal seizures | 10.3 (15) |

| Focal status epilepticus | 5.4 (8) |

- Abbreviations: ASM, antiseizure medication; EEG, electroencephalography; NLLOE, non-lesional late-onset epilepsy.

- a Pattern: sporadic paroxysmal discharges.

Short-term epilepsy and cognitive outcomes of the NLLOE population

At 12 months, 133 patients (97.8%) were taking ASM, of whom 126 (94.7%) were seizure-free (Table 2). At NP2 (n = 101), cognitive impairment worsened in 48 patients (47.6%) and improved in 29 (28.7%).

| Percentage (n = 136) | |

|---|---|

| Under antiseizure medication | 97.8 (133) |

| Seizure free | 94.7 (126) |

| Monotherapy | 98.5 (131) |

| Second neuropsychological assessment (n = 101) | |

| Improvement | 28.7 (29) |

| Decrease | 47.6 (48) |

| Stable | 23.7 (24) |

Comparison of clinical and paraclinical features according to the different presumed aetiology subtypes

After the initial evaluation, patients were classified into four different groups according to presumed aetiology: NDS (n = 31, 21%), MVS (n = 39, 27%), IFS (n = 9, 6%) and ULS (n = 67, 46%) (Table 3).

| Aetiology | Neurodegenerative (n = 31) | Microvascular (n = 39) | Inflammatory (n = 9) | Unlabelled (n = 67) | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First seen through the neurovascular emergency pathway, % (n) | 32.3 (10)e | 61.5 (24) | 22.2 (2)e | 22.4 (15)e | < 0.01c |

| Sex (F/M), % (n) | 58.1 (18) | 61.5 (24) | 33.3 (3) | 46.3 (31) | 0.27 |

| Autoimmune comorbidities, % (n) | 32.3 (10)g | 28.2 (11)g | 22.2 (2) | 6 (4) | < 0.01c |

| Psychiatric comorbidities, % (n) | 42 (13) | 17.9 (7)d | 11.1 (1) | 15 (10)d | < 0.01c |

| Known obstructive sleep apnoea, % (n) | 6.5 (2) | 7.7 (3) | 11.1 (1) | 7.5 (5) | 0.92 |

| Previous vascular history, % (n) | 78.1 (25) | 89.7 (35)g | 88.9 (8) | 65.7 (44) | <0.05c |

| High blood pressure, % (n) | 65 (20) | 69 (27)g | 78 (7) | 46 (31) | <0.05c |

| Initial cognitive complaint, % (n) | 78.1 (25) | 30.8 (12)d, g | 0d | 15 (10)d | < 0.01c |

| Age at epilepsy onset in years (mean ± SD) | 71.5 ± 10.8f, g | 74.8 ± 9.0f, g | 62.9 ± 8.5 | 66.1 ± 9.5 | < 0.01c |

| Age at diagnosis in years (mean ± SD) | 72.5 ± 10.6f, g | 76.5 ± 8.7f, g | 63.6 ± 7.7 | 67.5 ± 8.9 | < 0.01c |

| Epilepsy duration in months (mean ± SD) | 43.1 ± 28.7 | 41.6 ± 42.4 | 28.1 ± 16.9 | 47.4 ± 32.8 | 0.37 |

| Duration from cognitive complaint to seizure onset in months (mean ± SD) | 43.1 ± 28.7f | 14.5 ± 15.7f | 0 | 21 ± 15.6f | < 0.05c |

| Duration from seizure onset to NLLOE diagnosis in months (mean ± SD) | 15.5 ± 26.9 | 20.3 ± 36.3 | 11.2 ± 19.6 | 17.4 ± 30.7 | 0.84 |

| Seizure characteristics | |||||

| Focal status epilepticus, % (n) | 6.5 (2) | 2.6 (1) | 22.2 (2) | 4.5 (3) | 0.16 |

| Typical temporo-mesial seizures, % (n) | 19.4 (6) | 10.3 (4) | 22.2 (2) | 29.9 (20) | 0.052 |

| Aphasic seizures with/without motor deficit, % (n) | 28 (7)e | 64.7 (22) | 16.7 (1)e | 9.3 (5)e | < 0.01c |

| Lacunar amnesia, % (n) | 6.5 (2)f | 7.7 (3)f | 33.3 (3) | 17.9 (12) |

< 0.01c |

| Brain imaging characteristics | n = 28 | n = 39 | n = 9 | n = 66 | |

| Normal, % (n) | 17.9 (5)g | 5.1 (2)f, g | 44.4 (4) | 50 (33) | < 0.01c |

| Microvascular lesions, % (n) | 53.6 (15)e | 92.3 (36) | 11.1 (1)e | 30.3 (20)e | < 0.01c |

| Global atrophy, % (n) | 50 (14) | 30.8 (12) | 22.2 (2) | 21.2 (14)d | < 0.05c |

| Scheltens’ score (mean ± SD) | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 0.6 ± 1d | 0.2 ± 0.7d | 0.5 ± 1d | < 0.01c |

| Long-term EEG characteristics, % (n) | |||||

| Sporadic paroxysmal discharges | 77.4 (24) | 76.9 (30) | 77.8 (7) | 71.6 (48) | 0.94 |

| Spikes, polyspikes ± slow waves | 64.5 (20) | 59 (23) | 66.7 (6) | 67.2 (45) | 0.86 |

| Sharp waves | 48.4 (15) | 61.5 (24) | 88.9 (8) | 41.8 (28)f | < 0.01c |

| Generalized pattern | 3.2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1.5 (1) | 0.54 |

| Lateralized unilateral pattern | |||||

| Temporal or frontotemporal patterna | 54.8 (17) | 59 (23) | 88.9 (8) | 53.7 (36) | 0.09 |

| Extratemporal patterna | 0 | 10.3 (4) | 0 | 7.5 (5) | 0.92 |

| Bilateral independent pattern | 13 (4) | 15.4 (6) | 11.1 (1) | 10.4 (7) | 0.88 |

| Temporal or frontotemporal patterna | 6.5 (2) | 15.4 (6) | 11.1 (1) | 10.4 (7) | |

| Extratemporal patterna | 6.5 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Seizures | 6.5 (2) | 7.7 (3) | 0 | 14.9 (10) | 0.5 |

- Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalography; IFS, inflammatory subtype; MVS, microvascular subtype; NDS, neurodegenerative subtype; NLLOE, non-lesional late-onset epilepsy; ULS, unlabelled subtype.

- a Pattern: sporadic paroxysmal discharges.

- b p value unadjusted from comparisons using χ2 test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

- c Significant adjusted pairwise comparison with Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

- d p value <0.05 between NDS versus other subtypes using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney or Student's test for continuous variables.

- e p value <0.05 between MVS versus other subtypes using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney or Student's test for continuous variables.

- f p value <0.05 between IFS versus other subtypes using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney or Student's test for continuous variables.

- g p value <0.05 between ULS versus other subtypes using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney or Student's test for continuous variables.

Amongst the NDS, AD was diagnosed in 16 patients, LBD in three and FTD in two. NDS presented significantly more psychiatric comorbidities (p < 0.05) and initial cognitive complaints before NLLOE diagnosis (78.1%, p < 0.01). The mean duration from cognitive complaint to seizure onset was significantly longer (43.1 ± 28.7 months, p < 0.05).

In MVS, a higher proportion of patients were first seen in the neurovascular emergency pathway (61.5%, p < 0.01) and presented aphasic seizures (64.7%, p < 0.01). They were significantly older at seizure onset (74.8 ± 9.0 years old, p < 0.01).

Inflammatory subtype patients were significantly younger at seizure onset (62.9 ± 8.5 years old, p < 0.01) than MVS and NDS patients, and none had a cognitive complaint before their NLLOE diagnosis (p < 0.01). The duration between seizure onset and diagnosis was shorter (11.2 ± 19.6 months, p = 0.84). They tended to present more focal status epilepticus (22.2%, p = 0.16).

Unlabelled subtype patients presented significantly fewer vascular (p < 0.05) and autoimmune comorbidities (p < 0.05). They were younger than MVS and NDS patients (66.1 ± 9.5 years old, p < 0.01) and they had fewer initial cognitive complaints before their NLLOE diagnosis (15%, p < 0.01). Most seizures were typical temporo-mesial-type (auras defined as epigastric raise feeling, olfactory or gustatory hallucination, ‘déjà vu’ feeling of familiarity, interruption of ongoing activities, gestural and oral automatisms, postictal confusion) or transient amnesia-type seizures. They presented significantly fewer lesions on brain imaging than other patients (p < 0.01).

Short-term epilepsy and cognitive outcomes in the different presumed aetiological subtypes

Concerning seizure outcomes (Table 4), NDS patients had a lower seizure-free rate (77% NDS vs. 91% MVS vs. 86% IFS vs. 98% ULS, p < 0.05).

| Aetiology | Neurodegenerative | Microvascular | Inflammatory | Unlabelled | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy outcome (n = 138) | % (n = 31) | % (n = 36) | % (n = 7) | % (n = 64) | |

| Seizure free at 12 months | 77.4 (24) | 91.2 (33) | 86 (6) | 98.4 (63)c | <0.05b |

| First neuropsychological assessment (n = 137) | % (n’ = 31) | % (n’ = 37) | % (n’ = 9) | % (n’ = 60) | |

| Normal | 0 | 10.8 (4) | 0 | 20 (12) | <0.05b |

| Cognitive impairment | 29 (9) | 86.5 (32)c | 77.8 (7)c | 80 (48)c | <0.01b |

| Cognitive impairment with loss of autonomy | 71 (22) | 2.7 (1)c | 22.2 (2)c | 0 | <0.01b |

| Psychiatric involvement | 0 | 13.5 (5) | 0 | 5 (3) | 0.75 |

| Second neuropsychological assessment (n = 101) | % (n = 27) | % (n = 24) | % (n = 4) | % (n = 46) | |

| Stable | 11.1 (3) | 33.3 (8) | 25 (1) | 26.1 (12) | 0.13 |

| Decrease | 85.2 (23) | 29.2 (7)c | 25 (1)c | 34.8 (16)c | <0.01b |

| Improvement | 3.7 (1) | 37.5 (9)c | 50 (2)c | 39.1 (18)c | <0.01b |

| Normalization | 0 | 16.7 (4)c | 0 | 39.1 (18)c | <0.05b |

- Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalography; NDS, neurodegenerative subtype.

- a p value unadjusted from comparisons using χ2 test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

- b Significant adjusted pairwise comparison with Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

- c p value <0.05 between NDS versus other subtypes using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables.

At NP1, a normal cognitive profile was more frequent in ULS (20%, p < 0.05). In contrast, the ‘cognitive impairment with a loss of autonomy’ profile was more frequent in NDS (71%, p < 0.01). At NP2, cognitive decline was significantly more frequent in NDS (85.2%, p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The aetiology of epilepsy is a determining factor in the clinical course and prognosis of both seizure control and cognitive outcome. However, current classifications of epilepsy do not provide details of aetiology. In this article, a classification of the aetiologies of NLLOE is proposed. In this scheme, aetiologies are divided into four subtypes: neurodegenerative, microvascular, inflammatory and unlabelled. This prospective study of 146 patients is one of the first to propose and describe specific NLLOE phenotypes according to their presumed aetiology, along with their epileptic and cognitive prognosis.

Classification of NLLOE according to aetiology: what is the relevance?

The very concept of a single aetiology for epilepsy raises two major issues [14]. In most cases, epilepsy is multifactorial [15]. It is frequently the result of a combination of genetic and environmental factors. However, there is often a predominant cause to which epilepsy is attributed. This predominant cause plays a large part in the evolution and prognosis of epilepsy [6], which is clearly why this attribution is necessary and useful. Of course, identifying the cause is highly dependent on the degree of investigation. By carrying out a broad and exhaustive initial aetiological work-up in our study, an effort has been made to limit assignment errors.

It may be asked whether the aetiology of epilepsy still needs to be approached as a cause rather than a mechanism. Recent advances in molecular genetic techniques are revealing the molecular mechanisms underlying many genetic epilepsies [16]. Nonetheless, in most other epilepsies, mechanisms of epileptogenesis remain difficult to define. Just as there are a multiplicity of factors involved in epilepsy in different proportions, there are probably a multiplicity of underlying mechanisms [17]. So, until all the mechanisms underlying epilepsy are known, classification by main underlying cause remains relevant and justified.

Microvascular subtype

A specific patient profile was found in MVS, characterized by phasic disorders, which could mimic a transient ischaemic attack. In recent years, there is increasing evidence that NLLOE might often represent the first clinical manifestation of underlying white matter lesions (WMLs) in occult cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) [18-21]. In a large registry-based study [22], CSVD was more frequent in patients with epilepsy than in controls. Moreover, WML volume in CSVD was significantly increased in 16 NLLOE patients by comparison with age-matched controls [18]. In 2022, Urquia-Osorio et al. proposed the involvement of both deep and superficial WMLs in the spatial distribution of damaged brain networks involved in focal epilepsy [23].

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying CSVD are far from being fully elucidated. It has been postulated that CSVD disrupts cortical–subcortical circuits, leading to a subsequent imbalance between excitability and inhibitory pathways, and to epileptogenicity [24]. Moreover, in patients with CSVD, the neurovascular unit dysfunction due to altered integrity of the blood–brain barrier may lead to disruption of cerebral metabolism and/or perfusion with increasing risk of seizures [25]. Neuroinflammation that occurs in CSVD [26] is also deemed likely to contribute to epileptogenesis [27]. Ultimately, it is likely that CSVD should not be considered as a single disease but rather as a set of different pathologies with a variable risk of epileptogenesis. The coexistence of several factors such as genetic factors, cardiovascular risk factors, localization and severity of WMLs is responsible for the predisposition to epileptic seizures [28, 29].

Further studies are obviously required to better understand mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis in CSVD. Nevertheless, evidence seems sufficient to consider CSVD as a significant cause of NLLOE. This suggests that, in the case of recurrent transient phasic disorders, the epileptogenesis of CSVD should be discussed by practitioners.

Neurodegenerative subtype

Our results show that neurodegenerative aetiology appears to account for up to nearly a third of NLLOE aetiologies. This result is highly coherent with the general idea that there is a bidirectional link between epilepsy and cognitive impairment [30]. It is now widely accepted that seizures can occur in patients with neurodegenerative disease and that related neuropathological alterations might be a causative factor for late-onset unprovoked seizures [31, 32]. Patients with all types of dementia are five to 10 times more likely to develop epilepsy than an age-matched population without dementia [33]. The risk of dementia increases with epilepsy, and epilepsy is a risk factor for developing cognitive impairment and finally dementia [2, 30, 32, 34].

Cognitive complaint preceded seizure onset by several years, which seemed to be specific to NSD. These results support the hypothesis that seizures are a marker of neurodegenerative disease progression and dementia stage characteristics. Nevertheless, the starting point of seizures in neurodegenerative disease and notably in AD remains controversial. Several studies have shown that the prevalence of seizures in AD appears to increase with the duration of the disease [34, 35], and that the mean interval between diagnosis of AD and seizure onset ranges from 3.6 to 6.8 years [35, 36]. However, seizures preceding the onset of cognitive decline have also been documented [35-37], probably reflecting the well-established fact that neuropathological changes in AD precede symptom onset by many years [38]. The seizure onset in AD was reported, on average, 4.6 years before cognitive symptom onset, according to several retrospective studies in a large population of AD patients [37]. These pieces of evidence have even led to the still debated hypothesis of an inaugural epilepsy syndrome in sporadic AD that might define an ‘epileptic variant’ of AD [39].

Inflammatory subtype

The inflammatory aetiology of epilepsy is well recognized and appears in the latest ILAE classification [5]. IFS patients were the youngest. This result is in agreement with Graus et al. [12] who showed that patients with epilepsy due to inflammatory aetiology are on average 10 years younger than epileptic patients from other aetiologies. They presented acute-onset epilepsy with notably no cognitive complaints before seizure onset and a shorter diagnostic delay. Our results are consistent with the different consensus guidelines for the diagnosis of inflammatory epilepsy, which have a subacute onset (rapid progression of less than 3 months) as a major criterion [40, 41].

Unlabelled subtype

Unlabelled subtype patients were younger and healthier than MVS and NDS patients at diagnosis, with fewer comorbidities and less brain damage on brain imaging. A lot of ULS patients presented typical temporo-mesial-type seizures (29.9%) or transient amnesia-type seizures (17.9%). Our ULS patients probably included older patients classically described in the literature as suffering from temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and, particularly, those with transient epileptic amnesia (TEA). Indeed, the clinical phenotype of our ULS patients is similar to the TEA phenotype reported in the literature: 62 years old on average at seizure onset without comorbidities and with the absence of lesions on brain imaging in 93.1% of cases [42, 43].

Short-term epilepsy outcomes

One of the most striking findings was the excellent seizure outcomes at 1 year of treatment with ASM. Ninety-five per cent of our patients treated with ASM were seizure-free, including 99.2% with monotherapy. Previous studies have shown that seizures in older patients responded well to ASM with efficient seizure control in approximately 80% of older adults [3, 44, 45]. Seizures were more difficult to control in NDS than in the other groups. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study [45] showing that, in 89 patients with NLLOE, the seizure-free rate at 12 months was significantly lower in patients with comorbid dementia. Most ASMs are effective at low doses in treating typical seizures in older adults [45, 46]. Therefore, these results highlight that the first ASM should be started at a lower dose with slow titration for better tolerance in older patients. If the first ASM is not well tolerated or ineffective, another should be rapidly substituted to avoid polytherapy.

Short-term cognitive outcomes

Our results suggest that NDS is associated with faster cognitive decline and poorer autonomy. Indeed, cognitive decline was two to three times higher in NDS, with deterioration found in 85.2% of patients at NP2 and only one patient who improved. It can be supposed that this faster and greater cognitive decline may be partly explained by the natural course of neurodegenerative disease with epilepsy as precipitating factor [47, 48].

Inflammatory subtype, MVS and ULS presented a good cognitive prognosis at follow-up, with 50%, 37.5% and 39.1% improvement and 25%, 33.3% and 26.1% stabilization respectively. In these aetiologies, cognitive decline could be corrected or stabilized by treating seizures. The goal of ASM would therefore be twofold: to improve seizures and cognitive function and to reduce epilepsy complications. ASM should be begun as soon as possible in the course of the disease and could notably improve patient quality of life.

In ULS patients, cognitive outcomes were variable with decline in 34.8%, improvement in 39.1% and stabilization in 26.1% of patients. This result reflects the heterogeneity of this population already highlighted in the literature. According to the studies, TLE in older people and especially TEA may be associated either with a high risk of developing neurodegenerative disease in the short term [39] or with a high chance of cognitive functions remaining stable more than 5 years after diagnosis [49, 50]. At present, ULS may include TLE patients with different subtypes and outcomes. To resolve this issue, prospective studies of long-term cognitive outcomes should be conducted.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has several strengths. First, the study was performed in a large, longitudinal and real-life cohort of NLLOE patients with short-term follow-up (12 months). Secondly, only patients with a consistent diagnosis of NLLOE confirmed by specialized epilepsy teams were included. Thirdly, systematic clinical and paraclinical evaluations with NP and long-term EEG were performed for all included patients. Fourthly, all data were collected prospectively, enhancing the ability to include a significant set of broad clinically relevant phenotypic variables.

Concerning the limitations of the study, first the inclusion of patients with NLLOE was certainly not exhaustive, whether due to misdiagnosis or simply because they never visited our hospital. Additionally, this investigation was conducted at a single tertiary referral centre in Nancy, France. It is possible that the NLLOE of our cohort would be more severe than that of NLLOE patients in general. These factors cause an unavoidable selection bias and limit the generalizability of our findings to other geographical settings. Secondly, missing data, particularly at paraclinical assessment and during follow-up, could generate classification bias when forming and monitoring subgroups.

CONCLUSION

As the world's population age, neurologists, geriatricians and emergency physicians will increasingly need to diagnose and manage patients with NLLOE. An accurate description of the NLLOE population and classification of its different phenotypes and aetiologies are crucial. Our results suggest that this aetiological approach might be of value in NLLOE, leading physicians to distinguish these patients on an early basis into different subgroups of patients sharing similar clinical and paraclinical phenotypes and outcomes. This classification could help physicians to better diagnose epilepsy, perform relevant additional investigations and improve patient care in a reasonable timeframe. Additionally, our work confirms that patients with epilepsy associated with neurodegenerative disease or CSVD have distinct presentation and outcomes, thus challenging the current ILAE aetiological classification, which does not individualize these aetiologies per se.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Salomé Puisieux: Conceptualization; investigation; funding acquisition; writing – original draft; methodology; validation; visualization; writing – review and editing. Natacha Forthoffer: Investigation; methodology. Louis Maillard: Writing – review and editing. Lucie Hopes: Writing – review and editing. Thérèse Jonveaux: Writing – review and editing. Louise Tyvaert: Conceptualization; investigation; writing – review and editing; validation; methodology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the patients for their participation in this project.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors declare that no funds, grants or other supports were received during the preparation of this paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. They confirm that they have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that the report is consistent with those guidelines.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.