The prevalence and correlates of self-reported cannabis use for medicinal, dual and recreational motives in Australia: Findings from the National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022/2023

Abstract

Introduction

Cannabis has been prescribed as a medicine in Australia since 2016. The current study aimed to conduct a descriptive, epidemiological investigation on the prevalence and correlates of cannabis use for different motives (recreational-only, medical-only or dual-use) in Australia. It also aimed to examine the correlates of different cannabis use motives.

Methods

The National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022/2023 was used to estimate the prevalence and correlates of cannabis use motives among Australians. Prevalence estimates were weighted to the population and multinomial logistic regressions were used to examine the impact of age, gender, frequency of use and some of the most common conditions for which cannabis is prescribed in Australia (i.e., chronic pain, cancer and anxiety) on cannabis use motives.

Results

The prevalence of medical-only cannabis use was 1.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.6, 1.4%), recreational-only use was 8.6% (CI 7.5, 9.7%) and dual-use was 1.9% (CI 1.3, 2.5%). Respondents who reported chronic pain had a stronger association with medical-only (relative risk ratio [RRR] = 8.10, p < 0.001) or dual-use motives (RRR = 5.17, p < 0.001) compared to recreational-only. Respondents who usually obtained cannabis via prescription had a stronger association with medical-only motives compared to dual-use (RRR = 10.55, p < 0.001). Greater frequency of use was more strongly associated with dual-use motives compared to recreational-only.

Discussion and Conclusions

The emergence of dual-use cannabis consumers is a conundrum for the current medicinal cannabis policy framework in Australia. Research on the potential harms associated with the dual-use and medical-only use of cannabis should be prioritised as prescriptions for medicinal cannabis increase and barriers to access are lessened.

1 INTRODUCTION

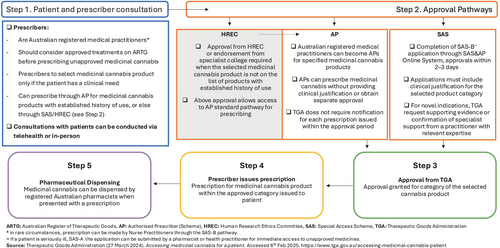

In Australia, medicinal cannabis has been prescribed since 2016. To legally allow medicinal cannabis to be prescribed, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol were rescheduled in the Poisons Standard in 2016 [1]. The Federal Government also amended the Narcotic Drugs Act in 2016 [1, 2] to facilitate the production, cultivation and manufacturing of medicinal cannabis in Australia. Only two cannabis products (Sativex and Epidyolex) have been approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). All other medicinal cannabis products are prescribed as unapproved medicines by a registered Australian medical practitioner (see Figure 1), when a clinical need cannot be addressed by an approved treatment [3]. Upon presentation of a valid prescription, registered pharmacists can dispense medicinal cannabis [4].

The last representative study on the prevalence of medicinal cannabis use estimated that less than 1.0% of the Australian population used cannabis medically, but these estimates are based on the previous wave of the National Drug Strategy Household Survey conducted in 2019 (NDSHS) [5]. Recent data suggest a surge in prescriptions in the past 5 years, potentially caused by the acceleration of prescription approval times in 2018 [6-8]. For-profit cannabis clinics promoting easier access through telehealth appointments opened soon after the expedition of these approval times [9]. To date, over $1 million in fines have been issued by the TGA to for-profit cannabis clinics for illegal and aggressive advertising, with some still breaching advertising guidelines [4, 10]. In light of the increasing commercialisation of Australia's medicinal cannabis framework, updating our prevalence estimates of cannabis use using the most current nationally representative data is essential.

Amidst the evolving influence of industry actors, the Australian Medical Association raised concerns about the increase in hospitalisations linked to the contraindicated prescription of medicinal cannabis [11]. They highlighted an increased demand for resources at public hospitals to manage presentations related to the use of high THC concentration medicinal cannabis products [12-14]. These concerns are in line with TGA data showing the commonly prescribed products are primarily composed of THC, with a ratio of ≥98% THC (the cannabinoid responsible for the psychoactive effects, or the ‘high’) to <2% cannabidiol [15]. Products with ≥98% THC are commonly cannabis flower and concentrates, largely identical to those used illicitly but perhaps more intoxicating with the same adverse effects [16]. Concordantly, the Australian Medical Association has recently cautioned the Federal Government about the recurrent prescription of cannabis for the treatment of chronic pain and anxiety, despite limited evidence supporting its efficacy for these conditions [17]. Of the 200+ conditions for which cannabis is prescribed in Australia, ~20% of prescription approvals have been to treat chronic pain, ~10% for anxiety and ~5% for sleep disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer, respectively [15]. Given these trends and the concerns from Australia's peak medical body, a timely investigation of the common health indications associated with medicinal cannabis use is warranted.

Within the increasingly commercialised Australian medicinal cannabis landscape, it has become difficult to discern the motivations for obtaining a medicinal cannabis prescription. The use of medicinal cannabis is legally sanctioned strictly for ‘medical-only’ use in Australia: consumption solely in accordance with a prescription to alleviate symptoms of a specific medical condition. However, questions remain about ‘dual-use’ consumers, who may use cannabis to treat a medical condition while also using it recreationally. Previous Australian studies have dichotomised respondents based on ‘any medicinal use’ or ‘recreational use’, yet this categorisation does not capture people who use cannabis for both motives [5, 18]. The NDSHS provides the necessary data to assess Australian's cannabis use motivations in three mutually exclusive classifications: only for medical purposes (herein: medical-only), not for medical purposes (herein: recreational-only), and both sometimes for medical purposes and sometimes for other reasons (herein: dual-use). Dual-use consumers have been found to obtain prescriptions for medicinal cannabis [6], albeit with inconsistent prescription patterns and with some self-medicating with illicit cannabis [7, 8]. In other jurisdictions, dual-use has shown to be associated with greater frequency of use, increased adverse effects and to be more likely in those who use cannabis to treat chronic pain [19, 20]. These factors highlight the importance of promptly examining dual-use cannabis consumers in Australia.

Other jurisdictions may serve as a valuable reference for understanding the demographic factors and cannabis use patterns that distinguish the different motives for cannabis use. Previous research from outside Australia has shown a positive association between daily cannabis use and medical cannabis use motives [18, 21-24]. Findings regarding gender and age are inconsistent within the literature, with some studies reporting an association between being male and recreational-only motives and others finding this association with medical-only consumers instead [18, 25]. Given the heterogeneity of these findings, it is essential to exploratively examine the relationship of age, gender and frequency of use on cannabis use motives in the Australian population.

The present study aimed to conduct a descriptive, epidemiological investigation on the prevalence of cannabis use for different motives in Australia using the most recent national-level survey data available [26]. To delineate the differences between Australians with different cannabis use motives, we examined the associations of where cannabis was obtained, frequency of use, common health indications and demographic variables on cannabis use motives. Based on extant literature and TGA data [15], we predicted that respondents who obtained cannabis through a prescription or were diagnosed/treated for chronic pain, anxiety or cancer may be postiviely associated with medical-only motives. Predictions regarding dual-use motives were not made due to the limited representative literature on this group in Australia.

2 METHOD

2.1 Study population

Data from the 2022/2023 cross-sectional Australian NDSHS were analysed [26]. The NDSHS collects data on respondents aged 14 and over from all states and territories in Australia reside in a household. The survey used stratified, multistage random sampling. The response rate was 43.9%. Contact was made with 49,389 in-scope households, of which 21,663 questionnaires were categorised as complete and usable. An ethics exemption was provided by The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (2024/HE000422).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Cannabis use frequency

Cannabis use frequency was assessed by the following questions: ‘Have you ever used Marijuana/Cannabis?’ with the possible responses of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. If yes, respondents were asked, ‘Have you used Marijuana/Cannabis in the last 12 months?’ with ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ as possible answers. Of respondents who answered ‘Yes’, they were then asked, ‘In the last 12 months, how often did you use Marijuana/Cannabis?’ with the possible responses of ‘Every day’, ‘Once a week or more’, ‘About once a month’, ‘Every few months’ and ‘Once or twice a year’. We retained these original categories from the NDSHS survey to enhance comparability across studies using this data.

2.2.2 Motives of cannabis use

Motives of cannabis use was assessed by the following question: ‘Have you used Marijuana/Cannabis for medical purposes in the last 12 months?’ with the possible responses of ‘Yes, only for medical purposes’, ‘Yes, but sometimes for medical purposes and sometimes for other reasons’ and ‘No, have not used it for medical purposes’.

2.2.3 Prescription of cannabis

Prescription of cannabis was measured by the following question: ‘Was the medical Marijuana/Cannabis prescribed by a doctor?’ with the possible responses ‘Yes, always prescribed by a doctor’, ‘Yes, sometimes prescribed by a doctor’ and ‘No, was not prescribed by a doctor’.

2.2.4 Source of cannabis

Source of cannabis was measured by the following question: ‘Where do/did you usually obtain Marijuana/Cannabis?’ with the possible responses: ‘Friend’, ‘Relative’, ‘Partner’, ‘Dealer’, ‘Prescription for medical condition’, ‘Internet’, ‘Grew/Grow my own’, ‘Stole/Steal it’ and ‘Other’. Social categories were combined (i.e., friend, relative, partner). Categories with low frequencies or ambiguity were excluded (i.e., internet purchases [n = 17], theft [n = 1], and other [n = 96]). The final categories were: Social, dealer, prescription and homegrown.

2.2.5 Respondent characteristics

Age was recoded as a categorical variable to classify age groups which relate to different life stages (e.g., young adults, older adults) to identify potential patterns in cannabis motive type. Genders other than female and male were recoded to missing and imputed as male or female due to low cell sizes in the original dataset.

2.2.6 Kessler psychological distress scale (K10)

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) variable was used as a validated proxy for psychological conditions, specifically anxiety. It is designed to score respondents' level of psychological distress from 0 to 50. The variable was dichotomised at ≥30 as a cut-off for very high risk of a psychological disorder and high specificity for anxiety [27, 28].

2.2.7 Chronic pain

Chronic pain was assessed via self-report, asking whether respondents had been diagnosed or treated for the condition in the past 12 months (‘No’, ‘Yes, diagnosed’, or ‘Yes, treated’). To ensure confidentiality, responses were aggregated by the source [26] yielding two categories: ‘Yes, diagnosed and/or treated’ and ‘No, not diagnosed or treated’.

2.2.8 Cancer

Cancer was assessed via self-report, asking whether respondents had been diagnosed or treated for the condition in the past 12 months (‘No’, ‘Yes, diagnosed’, or ‘Yes, treated’) and asked to write in the type of cancer. To ensure confidentiality, responses were aggregated by the source [26] yielding two categories: ‘Yes, diagnosed and/or treated’ and ‘No, not diagnosed or treated’.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Data missing at random were imputed using chained multiple imputations (MIs) with five iterations, as this approach reduces bias and does not require data to be missing completely at random [29, 30]. MI was conducted on the following variables: gender (1.9% missing), K10 psychological distress (1.4% missing), motives for cannabis use (1.3% missing) and the prescription of cannabis (1.0% missing). Absolute person sample weights and strata were applied to all analyses. We conducted descriptive analyses on the respondent predictors among respondents who used cannabis in the past 12 months (Table A1).

We conducted a multinomial logistic regression on cannabis use motives with respondent predictors (see Table A2, for crosstabulation) using imputed data (N = 2320, m = 5). For the outcome (i.e., cannabis use motives), we first used the recreational-only consumers as a reference group as it had the largest sample size, then we used dual-use (second largest) as the referent. For the respondent predictors, the following were used as referent groups as they were the largest: ‘people aged 26-35’, ‘males’, self-reported using cannabis ‘once or twice a year’, ‘not being diagnosed or treated for chronic pain’, ‘not being diagnosed or treated for cancer’ and ‘not having very high psychological distress’. ‘Dealer’ was used as the referent group for the source of cannabis to enable direct comparisons to illicit sources. Descriptive analyses were conducted on the rates of prescription separately as there was redundancy between this variable and the usual source of cannabis as a predictor. A conservative α level of p = 0.001 was applied to reduce the likelihood of false positives across multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using Stata 18 SE.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Prevalence of self-reported cannabis use motives

In the whole sample (N = 21,663), the weighted prevalence of self-reported, past year medical-only cannabis use was 1.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.6, 1.4%). Recreational-only cannabis use was self-reported by 8.6% (CI 7.5, 9.7%) of respondents and dual-use (both recreational and medicinal use) by 1.9% (CI 1.3, 2.5%). The majority of respondents, 88.5% (CI 87.2, 89.8%) did not report using cannabis in the past 12 months.

Among respondents who had used cannabis in the past 12 months (n = 2320), the weighted proportion who reported medical-only use was 8.8% (CI 7.5, 10.2%), recreational-only was 74.6% (CI 72.4, 76.8%) and dual-use was 16.6% (CI 14.7, 18.5%, see Table 1).

| N (unweighted) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole sample prevalence | 21,663 | – | – |

| Medical-only | 237 | 1.1% (1.0, 1.2%) | 1.0% (0.6, 1.4%) |

| Dual-use | 419 | 1.9% (1.8, 2.1%) | 1.9% (1.3, 2.5%) |

| Recreational-only | 1664 | 7.7% (7.3, 8.0%) | 8.6% (7.5, 9.7%) |

| Did not use cannabis in the past 12 months | 19,343 | 89.3% (88.9, 89.7%) | 88.5% (87.2, 89.8%) |

| Proportion among respondents who used cannabis in the past 12 months a | 2320 | – | – |

| Medical-only | 237 | 10.3% (9.1, 11.5%) | 8.8% (7.5, 10.2%) |

| Dual-use | 419 | 17.8% (16.3, 19.4%) | 16.6% (14.7, 18.5%) |

| Recreational-only | 1664 | 71.9% (70.0, 73.7%) | 74.6% (72.4, 76.8%) |

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

- a Missing data was imputed by chained multiple imputations.

3.2 Predictors of cannabis use motives

The model was statistically significant overall, F (32, 6835.6) = 12.55, p < 0.001. Estimates were based on multiple imputations (m = 5) for which the average relative increase in variance was 14.7%. A detailed examination of respondent predictor effects is presented in Table 2. Results are expressed in relative risk ratios (RRR), where risk is the probability of a specific cannabis use motive occurring in one predictor group compared to another.

| Variable | Level | RRR | SE | 95% CI | p | Variable | Level | RRR | SE | 95% CI | p | Variable | Level | RRR | SE | 95% CI | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||||||

| Medical-only versus recreational (reference) | Dual-use versus recreational (reference) | Medical-only versus dual-use (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age, years | Age, years | Age, years | ||||||||||||||||||

| 16–25 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.43 | <0.001* | 16–25 | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 1.04 | 0.070 | 16–25 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.71 | 0.007 | |||

| 26–35 (reference) | 26–35 (reference) | 26–35 (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 36–45 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 1.47 | 0.394 | 36–45 | 0.91 | 0.22 | 0.57 | 1.45 | 0.687 | 36–45 | 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 1.72 | 0.592 | |||

| 46–55 | 1.02 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 1.96 | 0.957 | 46–55 | 0.62 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 1.08 | 0.093 | 46–55 | 1.65 | 0.62 | 0.79 | 3.44 | 0.182 | |||

| 56–65 | 1.00 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 2.03 | 0.989 | 56–65 | 0.73 | 0.19 | 0.44 | 1.20 | 0.209 | 56–65 | 1.38 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 3.00 | 0.408 | |||

| 66+ | 1.05 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 2.32 | 0.907 | 66+ | 0.84 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 1.82 | 0.659 | 66+ | 1.25 | 0.59 | 0.49 | 3.17 | 0.641 | |||

| Gender | Gender | Gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 1.12 | 0.25 | 0.72 | 1.74 | 0.611 | Female | 2.22 | 0.38 | 1.58 | 3.12 | <0.001* | Female | 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.80 | 0.004 | |||

| Male (reference) | Male (reference) | Male (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of use | Frequency of use | Frequency of use | ||||||||||||||||||

| Every day | 3.85 | 1.43 | 1.85 | 8.04 | <0.001* | Every day | 11.33 | 3.36 | 6.33 | 20.28 | <0.001* | Every day | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.74 | 0.007 | |||

| Once a week or more | 1.52 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 3.29 | 0.283 | Once a week or more | 7.75 | 2.12 | 4.51 | 13.29 | <0.001* | Once a week or more | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.44 | <0.001* | |||

| About once a month | 1.54 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 3.69 | 0.328 | About once a month | 4.41 | 1.40 | 2.36 | 8.26 | <0.001* | About once a month | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.90 | 0.030 | |||

| Every few months | 0.89 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 1.91 | 0.770 | Every few months | 2.32 | 0.79 | 1.19 | 4.54 | 0.014 | Every few months | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 1.01 | 0.051 | |||

| Once or twice a year (reference) | Once or twice a year (reference) | Once or twice a year (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cancer | Cancer | Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 2.41 | 1.22 | 0.87 | 6.63 | 0.088 | Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 2.00 | 1.31 | 0.48 | 8.33 | 0.313 | Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 1.20 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 3.95 | 0.742 | |||

| Not diagnosed/treated (reference) | Not diagnosed/treated (reference) | Not diagnosed/treated (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chronic pain | Chronic pain | Chronic pain | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 8.10 | 2.06 | 4.92 | 13.34 | <0.001* | Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 5.17 | 1.10 | 3.40 | 7.85 | <0.001* | Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 1.57 | 0.38 | 0.97 | 2.53 | 0.065 | |||

| Not diagnosed/treated (reference) | Not diagnosed/treated (reference) | Not diagnosed/treated (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Psychological distress (K10) | Psychological distress (K10) | Psychological distress (K10) | ||||||||||||||||||

| High (>30) | 1.49 | 0.43 | 0.85 | 2.63 | 0.164 | High (>30) | 0.84 | 0.20 | 0.53 | 1.34 | 0.464 | High (>30) | 1.78 | 0.54 | 0.99 | 3.21 | 0.055 | |||

| Less than high (<30; reference) | Less than high (<30; reference) | Less than high (<30; reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Source | Source | ||||||||||||||||||

| Medical prescription | 101.20 | 59.66 | 31.85 | 321.49 | <0.001* | Medical prescription | 9.59 | 6.11 | 2.73 | 33.77 | <0.001* | Medical prescription | 10.55 | 4.21 | 4.79 | 23.24 | <0.001* | |||

| Self-grown | 2.70 | 1.36 | 0.99 | 7.34 | 0.052 | Self-grown | 1.43 | 0.45 | 0.76 | 2.66 | 0.265 | Self-grown | 1.89 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 5.21 | 0.215 | |||

| Social (friend, relative, partner) | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 1.23 | 0.201 | Social (friend, relative, partner) | 0.70 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 1.06 | 0.091 | Social (friend, relative, partner) | 0.97 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 1.83 |

0.935 |

|||

| Dealer (reference) | Dealer (reference) | Dealer (reference) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cons | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.10 | <0.001* | Cons | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.08 | <0.001 | Cons | 1.02 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 2.63 | 0.970 | |||

- Note: Imputed data only includes respondents who have used in the previous 12 months.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RRR, relative risk ratios.

- * p < 0.001.

3.2.1 Age

Relative to respondents aged 26–35, respondents aged 16–25 had less risk of reporting cannabis for medical-only motives, compared to recreational-only (RRR = 0.19, CI 0.08, 0.43, p < 0.001).

3.2.2 Gender

Compared to males, females had a higher risk of reporting dual-use (RRR = 2.22, CI 1.58, 3.12, p < .001) compared to recreational-only use motives.

3.2.3 Frequency of use

Relative to respondents who self-reported using cannabis once or twice a year (reference), respondents who reported using cannabis every day had a higher risk of reporting medical-only cannabis use (RRR = 3.85, CI 1.85, 8.04, p < 0.001), compared to recreational-only use.

Using the same reference group, respondents who reported using cannabis every day (RRR = 11.33, CI 6.33, 20.28, p < 0.001), once a week or more (RRR = 7.75, CI 4.51, 13.29, p < 0.001) or about once a month (RRR = 4.41, CI 2.36, 8.26, p < 0.001) had a higher risk of reporting dual-use compared to recreational-only use motives.

Relative to the same reference group, respondents who used cannabis once a week or more (RRR = 0.20, CI 0.09, 0.44, p < 0.001) had less risk of medical-only motives compared to dual-use.

3.2.4 Cancer

Being diagnosed or treated for cancer was not associated with an greater or lower risk of any cannabis use motive type.

3.2.5 Chronic pain

Relative to respondents without chronic pain, those with chronic pain had a greater risk of reporting cannabis use for medical-only motives, compared to recreational-only (RRR = 8.10, CI 4.92, 13.34, p < 0.001). The same pattern was observed for dual-use consumers compared to recreational-only (RRR = 5.17, CI 3.40, 7.85, p < 0.001).

3.2.6 Psychological distress

Having high psychological distress levels indicative of an anxiety disorder was not associated with greater or lower risk of any cannabis use motive type.

3.2.7 Source of cannabis

Relative to respondents who obtained cannabis from a dealer, those respondents who usually obtained cannabis with a prescription had a greater risk of reporting cannabis use for medical-only motives, compared to recreational-only (RRR = 101.20, CI 31.85, 321.49, p < 0.001). The same pattern was observed for dual-use motives compared to recreational-only (RRR = 9.59, CI 2.73, 33.77, p < 0.001); and for medical-only motives compared to dual-use (RRR = 10.55, CI 4.79, 23.24, p < 0.001).

3.3 Rates of prescription of medicinal cannabis

Among respondents who reported always being prescribed cannabis, 70.6% (CI 67.5, 84.7%) were medical-only consumers and 29.4% (CI 20.3, 50.4%) were dual-use consumers. Of respondents who reported they had sometimes been prescribed cannabis, 67.3% (CI 46.2, 69.4%) were dual-use consumers and 32.7% (CI 15.2, 38.2%) were medicinal-only consumers (see Table A2).

4 DISCUSSION

Within the Australian population in 2022/2023, the prevalence of self-reported medical-only cannabis use was 1.0%; dual-use motives (both medicinal and recreational) were more common (1.9%), but the majority of Australians still used cannabis for recreational-only motives (8.6%). Among past-year cannabis consumers, the proportion of Australians who used cannabis for medical-only motives in 2022/2023 was a minority (8.8%) compared to those who reported using cannabis for dual-use (16.6%) or recreational-only (74.7%) motives.

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first population level studies to demonstrate that a substantial number of Australians have dual-use cannabis motives. Notably, these respondents self-report alternating between different cannabis use motives (i.e., medical and recreational) which demonstrates nuanced motives for cannabis use in Australia that can no longer be dichotomised simply as medical or recreational [5]. Dual-use is a conundrum for medicinal cannabis regulation as Australian law treats cannabis as a prescription medication that should only be used as prescribed [31], which is likely violated by dual-use consumers. Using medicinal cannabis products as both a medication and a recreational substance may increase the likelihood of an escalating or a disordered use pattern through a number of pathways, one being increased frequency of use [32-34]. Our results demonstrate that Australians who reported more frequent patterns of use may have a greater likelihood of being a dual-use consumer compared to recreational-only. There is the concern that the combination of using cannabis as prescribed in addition to recreational use may increase the individual's overall frequency of use, placing them at higher risk of cannabis use disorder (CUD) which is prevalent (22–25%) among both recreational and medical cannabis consumers [35, 36]. Interestingly, respondents with medical-only motives were only more likely to be daily cannabis consumers when compared to recreational use, which may be reflective of adherence to a prescribed daily medication regime, particularly when considering that medical-only consumers were less likely to use cannabis once a week or more compared to dual-use consumers. We acknowledge that these findings require a deeper investigation, perhaps in a dataset with more nuanced cannabis consumption items, to seperate the potential differences in frequency of use between medical-only and dual-use consumers.

The frequent prescription of THC dominant products like cannabis flower and concentrates in Australia may be related to dual-use cannabis motives, as these products are akin to what is used recreationally, with previous research demonstrating an association between cannabis product type and motives for use [18]. The NDSHS does not allow the investigation of these factors, but future research should seek to understand the role of cannabis product type, cannabis potency and the route of administration on cannabis use motives in Australia [21, 25, 37].

When discussing dual-use consumers, it is important to consider the possibility that some dual-use consumers desire to avoid legal harms rather than primarily using cannabis for medicinal motives [34, 38]. The current results suggest that medical-only consumers may be more likely to usually obtain cannabis through a prescription compared to dual-use consumers, which may indicate that dual-use consumers sometimes use the medicinal pathway as a backdoor for recreational use. It could also suggest that respondents sometimes self-medicated with illicit cannabis as has been found in other jurisdictions [18], especially given that only 70.6% of medical-only consumers reported always obtaining cannabis via a prescription.

Respondents who reported having chronic pain were more likely to be medical-only or dual-use consumers than recreational-only consumers, which aligns with data from the TGA showing that chronic pain is the most common indication for which medicinal cannabis is prescribed [15]. The observed association between chronic pain and the dual or medical-only use of cannabis raises concerns, given The Faculty of Pain Medicine and the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists have issued a recommendation that Australian doctors should not prescribe medicinal cannabis to treat patients with chronic, non-cancer pain unless a part of a registered clinical trial, as there remains insufficient evidence to justify the endorsement of its clinical use [39]. There are other concerns among peak bodies about the elevated risk of psychotic symptoms associated with the use of medicinal cannabis for chronic pain and the potential for an increased risk of CUD [19, 36]. Given these risks, there is an urgent need for future research on CUD in Australians with dual-use cannabis motives.

It is important to note that chronic pain was reported independent of cannabis use (i.e., it was not stated which condition medicinal cannabis was used for), thus the endorsement of chronic pain may not imply medicinal cannabis was used to treat this specific condition. The measurement of medical conditions was limited by the data available, such that we were unable to test the associations of some frequently prescribed indications (sleep problems and post-traumatic stress disorder were absent) which may have introduced bias due to unmeasured medical conditions. The NDSHS only asks 15 questions about cannabis use specifically, as the purpose of this survey is broader. The strength of the NDSHS is that it is nationally representative and conducted every 3 years, unlike any other cannabis-related questionnaire conducted on an Australian sample. Our ability to inform causality was limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data. The results rely on self-reported survey data from respondents who live in households, so data may therefore be impacted by response biases, such as social desirability, and cannot represent vulnerable populations who do not reside in a home, such as respondents receiving in-patient treatments and unhoused and incarcerated respondents.

5 CONCLUSION

In 2022/2023, the population prevalence of medical-only cannabis use in Australia was estimated at 1.0%, recreational-only use was 8.6%, and dual-use was 1.9%. The emergence of dual-use consumers is a conundrum for the medicinal cannabis policy framework, with this group reporting both recreational and medicinal motives for use, alongside lower rates of consistent prescriptions for cannabis and more frequent use of cannabis compared to recreational-only consumers. Respondents with chronic pain were at increased likelihood of using cannabis for medical-only or dual-use motives, which requires further monitoring given peak body recommendations to cease prescribing for the condition. The potential harms associated with the dual-use and medical-only use of cannabis require future research as prescriptions for medicinal cannabis are increasingly being written and barriers to access are being removed.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Each author certifies that their contribution to this work meets the standards of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022/23 data was sourced from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley - The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

| Variable | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| 16–25 | 16.3% (14.7, 17.87%) | 26.4% (23.7, 29.1%) |

| 26–35 | 25.8% (24.0, 27.6%) | 28.1% (25.8, 30.4%) |

| 36–45 | 20.2% (18.5, 21.8%) | 17.8% (15.9, 19.6%) |

| 46–55 | 16.5% (14.9, 18.0%) | 14.2% (12.5, 15.9%) |

| 56–65 | 13.5% (12.0, 14.9%) | 9.0% (7.7, 10.3%) |

| 66+ | 7.8% (6.7, 8.9%) | 4.6% (3.6, 5.5%) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 45.6% (43.5, 47.6%) | 43.1% (40.5, 45.6%) |

| Male | 54.4% (52.4, 56.5%) | 56.9% (54.4, 59.5%) |

| Cancer | ||

| No, not diagnosed and/or treated | 96.1% (95.3, 96.9%) | 97.5% (96.8, 98.2%) |

| Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 3.9% (3.1, 4.7%) | 2.5% (1.8, 3.2%) |

| Chronic pain | ||

| No, not diagnosed and/or treated | 83.0% (81.4, 84.6%) | 86.2% (84.6, 87.8%) |

| Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 17.0% (15.4, 18.6%) | 13.8% (12.2, 15.4%) |

| Psychological distress | ||

| No | 87.3% (85.9, 88.6%) | 86.1% (84.2, 88.0%) |

| Very high | 12.7% (11.4, 14.1%) | 13.9% (12.0, 15.8%) |

| Frequency of use | ||

| Every day | 19.4% (17.7, 21.0%) | 18.9% (16.8, 20.9%) |

| Once a week or more | 22.1% (20.3, 23.9%) | 21.0% (18.8, 23.1%) |

| About once a month | 11.4% (10.1, 12.7%) | 11.3% (9.6, 12.9%) |

| Every few months | 16.2% (14.7, 17.7%) | 17.3% (15.2, 19.3%) |

| Once or twice a year | 30.9% (28.9, 33.0%) | 31.6% (29.1, 34.2%) |

| Source | ||

| Dealer | 19.8% (18.2, 21.4%) | 21.6% (19.3, 23.9%) |

| Social (friend, relative, partner) | 69.7% (67.8, 71.6%) | 69.9% (67.4, 72.4%) |

| Medical prescription | 5.2% (4.3, 6.1%) | 4.9% (3.8, 5.9%) |

| Self-grown | 5.2% (4.3, 6.2%) | 3.6% (2.8, 4.4%) |

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

- [Correction added on 19 May 2025, after first online publication: In Table A1, the ‘Male’ and ‘Female’ entries under the ‘Variable’ column have been swapped.]

| Variable | Medical-only | Dual use | Recreational only | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | 95% CI | ||||

| Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| 16–25 | 3.5% (1.7, 5.4%) | 2.4% (0.8,4.0%) | 13.7% (10.2,17.2%) | 13.5% (9.4, 17.6%) | 82.8% (78.9, 86.7%) | 84.1% (79.7, 88.4%) |

| 26–35 | 7.8% (5.6, 9.9%) | 7.9% (5.3, 10.6%) | 16.9% (13.8, 19.9%) | 16.8% (12.9, 20.7%) | 75.4% (71.9, 78.9%) | 75.3%(70.7, 79.8%) |

| 36–45 | 9.8% (7.1, 12.5%) | 9.5% (6.3, 12.7%) | 17.9% (14.4, 21.5%) | 19.1% (14.6, 23.7%) | 72.3% (68.2,76.4%) | 71.4% (66.3, 76.5%) |

| 46–55 | 14.8% (11.2, 18.4%) | 15.2% (10.6, 19.8%) | 16.2% (12.5, 20.0%) | 14.1% (10.0, 18.2%) | 68.9% (64.3, 73.6%) | 70.7% (65.0, 76.3%) |

| 56–65 | 14.7% (10.7, 18.7%) | 15.1% (9.8, 20.4%) | 24.3% (19.5, 29.1%) | 20% (14.9, 25.1%) | 61.1% (55.6, 66.6%) | 64.9% (58.3, 71.4%) |

| 66+ | 17.1% (11.6, 22.7%) | 16.5% (11.4, 19.5%) | 21.5% (15.5, 27.6%) | 24% (16.5, 31.2%) | 61.3% (54.1, 68.5%) | 59.6% (48.7, 67.3%) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 10.6% (8.7, 12.4%) | 8.0% (6.2, 9.9%) | 20.2% (17.8, 22.6%) | 20.5% (17.3, 23.7%) | 69.2% (66.4, 72.0%) | 71.5% (68.0, 75.0% |

| Male | 10.1% (8.4, 11.8%) | 9.4% (7.5, 11.4%) | 15.8% (13.8, 17.9%) | 13.6% (11.3, 15.9%) | 74.1% (71.6, 76.5%) | 77.0.% (74.1, 79.9%) |

| Cancer | ||||||

| Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 28.5%(17.7, 39.2%) | 28.7% (17.5, 39.9%) | 33.7% (16.8, 50.7%) | 33.8% (16.4, 51.0%) | 37.8% (23.9, 51.6%) | 37.5% (22.3, 52.3%) |

| No, not diagnosed and/or treated | 9.6%(8.3, 10.8%) | 8.4%(7.0, 9.7%) | 17.3% (15.6, 18.9) | 16.2% (14.2, 18.1%) | 73.2% (71.3, 75.0%) | 75.5% (73.2, 77.7%) |

| Chronic pain | ||||||

| Yes, diagnosed and/or treated | 30.8% (26.2, 35.5%) | 30.7% (24.7, 36.7%) | 36.6% (31.7, 41.5%) | 35.2% (29.2, 41.2%) | 32.6% (27.9, 37.3%) | 34.1% (28.0, 40.2%) |

| No, not diagnosed and/or treated | 6.1% (5.0, 7.2%) | 5.3% (4.1, 6.5%) | 14.0% (12.4, 15.5%) | 13.6% (11.6, 15.6%) | 79.9% (78.1, 81.7%) | 81.1% (78.9, 83.3%) |

| Psychological Distress (K10) | ||||||

| High (>30) | 15.1% (10.9, 19.2%) | 12.8% (8.3, 17.4%) | 25.1% (20.1, 30.1%) | 20.3% (14.8, 17.4%) | 59.9% (54.2, 65.5%) | 66.8% (60.1, 73.5%) |

| Less than high (<30) | 9.6% (8.3, 10.9%) | 8.2% (6.8, 9.6%) | 16.8% (15.1, 18.4%) | 16.0% (13.9, 18.0%) | 73.6% (71.7, 75.6%) | 75.9% (73.6, 78.2%) |

| Frequency of use | ||||||

| Every day | 21.8%(17.7, 25.8%) | 21.4% (16.4, 26.4%) | 31.3% (26.9, 35.8%) | 31.6% (25.8, 37.4%) | 46.9% (41.8, 52.0%) | 47.0% (40.7, 53.3%) |

| Once a week or more | 11.7%(8.8, 14.6%) | 9.0% (6.0, 12.0%) | 29.1% (25.2, 33.1%) | 26.5% (21.7, 31.2%) | 59.1% (54.8, 63.5%) | 64.5% (59.1, 69.8%) |

| About once a month | 8.8% (5.2, 12.4%) | 7.3% (3.3, 11.2%) | 17.5% (12.9, 22.2%) | 16.9%(11.2, 22.7%) | 73.7% (68.3, 79.1%) | 75.8% (69.0, 82.6%) |

| Every few months | 5.3% (2.7, 7.8%) | 4.4% (2.1, 6.8%) | 11.1%(7.8, 14.4%) | 10.2% (5.5, 14.9%) | 83.7% (79.7, 87.6%) | 85.4% (80.4, 90.4%) |

| Once or twice a year | 5.3%(3.7, 7.0%) | 4.3%(2.6, 5.9%) | 5.2%(3.5, 6.8%) | 4.6% (2.8, 6.3%) | 89.5%(87.2, 91.8%) | 91.2% (88.8, 93.6%) |

| Source | ||||||

| Dealer | 5.6% (4.4, 6.7%) | 4.6% (3.4, 5.9%) | 14.4% (12.6, 16.1%) | 12.7% (10.6, 14.7%) | 80.1% (78.1, 82.0%) | 82.7%(80.4, 85.1%) |

| Social (friend, relative, partner) | 9.3% (6.4, 12.2%) | 7.1% (4.0, 10.1%) | 25.2% (21.1, 29.2%) | 24.8% (19.7, 29.9%) | 65.6% (60.9, 70.2%) | 68.1% (62.4, 73.9%) |

| Medical prescription | 75.2% (67.0, 83.5%) | 69.6% (54.2, 76.1%) | 21.3% (13.6, 29.0%) | 25.2% (20.2, 33.8%) | 3.5% (0.0, 7.1%) | 5.3%(1.6, 9.8%) |

| Self-grown | 12.2% (6.1, 18.2%) | 18.7% (7.7, 29.7%) | 32.7% (24.2, 41.2%) | 31.2% (21.0, 41.4%) | 55.1% (46.1, 64.1%) | 50.1% (38.3, 62.0%) |

| Crosstabulation of cannabis use type and self-reported prescription patterns | Medical-only | Dual use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||

| Unweighted | Weighted | Unweighted | Weighted | |

| Prescription use | ||||

| Yes, always prescribed by a doctor | 77.2% (70.1, 84.3%) | 70.6% (67.5, 84.7%) | 37.1% (22.8, 51.4%) | 32.7% (20.3, 50.4%) |

| Yes, sometimes prescribed by a doctor | 22.8% (15.7, 29.9%) | 29.4% (15.2, 31.2%) | 62.9% (48.6, 77.2%) | 67.3% (46.2, 69.4%) |

- Note: Based on imputed data which only includes respondents who used cannabis in the previous 12 months.

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

- [Correction added on 19 May 2025, after first online publication: In Table A2, the ‘Variable’ column contained mixed data for Female and Male. This has now been corrected.]

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Australian Institute of Health and Welfare at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/national-drug-strategy-household-survey/contents/about.