Thyroid FNA cytology in Asian practice—Active surveillance for indeterminate thyroid nodules reduces overtreatment of thyroid carcinomas

Abstract

Although Asian thyroid practices have implemented the American Thyroid Association guidelines, significant deviations in actual risk of malignancy (ROM) have been reported. With review of the literature from Asia, the authors examine the underlining reasons for actual ROMs reported in Asia being so different from western practice based on the author's perspective. Although the most popular diagnostic system for thyroid cytology used in Asian countries is the Bethesda system, the Japan Thyroid Association published clinical guidelines, including a national reporting system for thyroid cytology, to adapt conservative clinical management (active surveillance and strict triage patients for surgery) for low-risk thyroid carcinomas. As less aggressive clinical management is favoured in Asian societies, strict triage of patients with indeterminate thyroid nodules for surgery is usually applied, which ultimately reduces overtreatment of indolent thyroid tumours. As a result, low resection rates and high ROMs for indeterminate nodules were achieved in Asian practices using the same Bethesda system. Recently, borderline thyroid tumours were introduced in the thyroid tumour classification and significant decreases in ROMs have been reported in the indeterminate categories in western practice. However, ROM of indeterminate nodules remained high in Asian practice even after borderline tumours were deemed benign. These results suggested that the diagnostic threshold of papillary thyroid carcinoma-type nuclear features varied among practices (stricter in Asia than in western practice), and diagnostic surgery was not performed for a significant number of indeterminate nodules with benign clinical features in Asian practice, resulting in low rates of borderline tumours in surgically-treated patients.

Abstract

Although Asian thyroid practices have implemented the American Thyroid Association guidelines and the Bethesda system for reporting thyroid cytopathology, significant deviations in actual risk of malignancy have been reported. With review of the literature and analyses of thyroid practices in Asia, the author examines the underlining reasons why actual ROMs reported in Asia are so different from those in Western practice based on the author's perspective.

1 INTRODUCTION

Thyroid FNAC is the most useful test to either confirm or exclude cancer. Therefore, this procedure is the first line clinical test as it is a safe, cost effective and accurate method for patients with thyroid nodules.1-3 However, a substantial number of thyroid nodules (20%-25%) are classified in the so-called indeterminate category (atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance [AUS/FLUS], follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm [FN/SFN] or suspicious for malignancy [SM]) on preoperative FNA,4, 5 which poses difficulties for management. Thus, many authors and clinical guidelines have devoted much attention to how to handle patients with cytologically indeterminate thyroid nodules.1-5 The American National Institutes of Health system for reporting thyroid FNAC (Bethesda system) aimed to improve diagnosis of indeterminate thyroid nodules. Its strategies include: (1) more precise and defined standardised nomenclature and morphological criteria; (2) the indeterminate category was divided into lower-risk (AUS/FLUS); intermediate-risk (FN/SFN) and higher-risk (SM); (3) risks of malignancy (ROMs) were estimated in each cytological category to serve as a quality control guide; (4) the target number of AUS/FLUS was set at less than 7% to minimise its overuse; and (5) clinical management of cytological categories were defined for improved communication among patients, cytopathologists and clinical doctors.4, 5 Many reports have confirmed its high overall accuracy, and concluded that the Bethesda system was reliable and valid.6-12 However, there are unforeseen consequences for thyroid cancer treatment that were not appreciated prior to 2009, when the first edition of Bethesda system and the 2009 Revised American Thyroid Association (ATA) management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differential thyroid cancers were published. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of indolent thyroid cancers has been highlighted by epidemiologists,13, 14 and further confirmed by Korean experience,15 in which the ATA thyroid cancer management guidelines and the Bethesda system were implicated.

In this opinion paper, the authors introduce Asian practices for patients with thyroid nodules and describe Asian clinical practice (active surveillance for indeterminate thyroid nodules and low-risk thyroid carcinomas), as reliable and valid means for reducing overdiagnosis and overtreatment of borderline thyroid tumours and low-risk thyroid carcinomas.16, 17 In addition, there are reports of significant variations in ROM in cytological-histological correlation studies even when the ATA thyroid cancer management guidelines and the Bethesda system were employed.6, 9-11, 18-22 This article presents high quality data provided by members of the Working Group of Asian Thyroid FNA Cytology,22-29 which confirms high ROMs in the indeterminate FNA categories and low rates of non-invasive follicular neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP) in most Asian thyroid FNA practice.20, 22, 30 This article also provides an overview of Asian thyroid FNAC practice and gives possible reasons for the significant differences between Asian and western practice.

2 REVIEW OF REPORTS BY MEMBERS OF THE WORKING GROUP OF ASIAN THYROID FNAC IN ENGLISH

2.1 China

Zhu et al published their thyroid FNA practice in 2015.31 They used haematoxylin-eosin staining and the five-tiered British system for diagnosis. Resection rates (RRs) were low at 41.6% in Thy 3, and ROMs were high in Thy 3 (51.9%) and Thy 4 (92.9%). Zhu et al further applied subclassification to the Thy 3 category, dividing it into four subcategories: Thy 3-PTC (papillary thyroid carcinoma), Thy 3-FN (follicular neoplasm), Thy 3-HN (Hürthle cell neoplasm) and Thy 3-FL (follicular lesion). ROMs for each were 71.4%, 46.2%, 42.9% and 27.3%, respectively.31 Their skilful approach to subclassification of the Thy 3 category made it possible to calculate the ROM of AUS/FLUS (Thy 3-PTC + Thy 3-FL) and FN/SFN (Thy 3-FN), and compare it with the Bethesda system. According to this interpretation, their ROM of AUS/FLUS was 56.3% (18/32) and the ROM of FN/SFN was 46.2% (6/13), higher than implied ROMs by the Bethesda system. Of note, cancer surgery comprised 86% (631 cases) of all 734 surgically-treated patients and the proportion of Thy 5 was high at 49.3%,31 which is an extremely high proportion malignant FNA category in comparison with the average 7.4% (range: 2.7%-16.2%) of 11 reports by Sheffield et al.11 The authors attributed this to excessive institutional work load and a manpower shortage. The authors of this article emphasise that shortages of laboratory personnel may force Asian practice to concentrate more on advanced stage cancers and potentially lethal cancers, and postpone treatment of biologically more indolent borderline or precursor tumours, small early cancers and lower-risk cancers by strict triage of only higher-risk patients for surgery.

Liu et al28 published their results for thyroid FNA using the Bethesda system on haematoxylin-eosin stained samples. Out of 2838, 791 (27.9%) FNAs were surgically-treated, and the ROM of all resected nodules was 85.1% (673/791) and that of all FNA samples was 23.7% (673/2838). ROMs for six categories were 0% for non-diagnostic, 6.5% for benign, 71.4% for AUS/FLUS, 66.7% for FN/SFN, 69% for SM and 97.0% for the malignant category for 791 resected nodules.28 They classified cyst fluid-only samples differently in the benign category, a modification from the Bethesda system. The ROM of all resected nodules was also high at 85.1%, and the proportion of FNAs in the malignant Bethesda category was high at 30.6%.28

2.2 India

Agarwal and Jain29 described their thyroid FNA practice in India, an area with a high prevalence of endemic goitre due to iodine deficiency.30 Two hundred and fifty (18.7%) patients were surgically-treated for 1339 FNA nodules, and the ROM for all resected nodules was 58.8% (147/250) and that for all FNA samples was 11.0% (147/1339). The RRs of the six Bethesda categories were 8.9% (non-diagnostic), 9.2% (benign), 23.8% (AUS/FLUS), 43.9% (FN/SFN), 54.0% (SM) and 38.7% (malignant), respectively. The ROMs of six Bethesda categories were 21.7% (non-diagnostic), 22.8% (benign), 34.3% (AUS/FLUS), 72.0% (FN/SFN), 92.6% (SM) and 96.6% (malignant; Table 1). Their ROMs for AUS/FLUS and SM were high, and that for FN/SFN nodules was higher than implied ROMs using the Bethesda system.

| Author (Country) [reference] | Risk of malignancy, % (number of malignant diagnoses/number of resected nodules) | ROM in all resected nodules | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bethesda I (non-diagnostic) | Bethesda II (benign) | Bethesda III (AUS/FLUS) | Bethesda IV (FN/SFN) | Bethesda V (SM) | Bethesda VI (Malignant) | ||

| Limlunjakorn (Thailand)37 | 19.2 (20/104) | 14.0 (29/207) | 37.9 (11/29) | 20.9 (9/43) | 81.5 (22/27) | 93.6 (44/47) | 29.5 (135/457) |

| Hang (Taiwan)26 | 16.7 (5/30) | 6.5 (10/155) | 41.7 (10/24) | 21.1 (4/19) | 75.0 (12/16) | 97.2 (139/143) | 46.5 (180/387) |

| Satoh (Japan)24 | 17.3 9/52) | 8.5 (6/71) | 14.3 (5/35) | 26.6 (17/64) | 93.3 (28/30) | 100 (158/158) | 54.4 (223/410) |

| Hong (Korea 1) [personal communication] | 35.7 (10/28) | 32.6 (14/43) | 60.5 (46/76) | 73.3 (11/15) | 88.0 (22/25) | 100 (145/145) | 74.7 (248/332) |

| Jung (Korea 2) [personal communication] | 50.0 (4/8) | 4.8 (1/21) | 75 (12/16) | 50 (1/2) | 94.1 (16/17) | 100 (144/144) | 85.6 (178/208) |

| Agarwal (India)29 | 21.7 (5/23) | 22.8 (13/53) | 34.3 (12/35) | 72.0 (36/50) | 92.6 (25/27) | 96.6 (56/58) | 58.8 (147/250) |

| Average (range), % | 26.8 (16.7-50.0) | 14.9 (4.8-32.6) | 44.0 (14.3-75) | 44.0 (20.9-73.3) | 87.4 (75.0-94.1) | 97.9 (93.6-100) | 60.4 (29.5-85.6) |

- AUS/FLUS, atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance; FN/SFN, follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm; SM, suspicious for malignancy; ROM, risk of malignancy.

They conducted an extensive literature search of reports published from India on thyroid FNAC and found 28 out of 50 studies that met the inclusion criteria for their meta-analysis.29 Most thyroid aspiration samples were collected by pathologists using manual palpation, and the Bethesda system is the most widely used reporting system in India. This meta-analysis revealed that ROMs (average and 95% confidence interval) for the six Bethesda categories were 15% (6%-24%) for non-diagnostic, 3% (2%-4%) for benign, 34% (23%-45%) for AUS/FLUS, 26% (15%-36%) for FN/SFN, 69% (55%-84%) for SM and 94% (89%-98%) for malignant.29 The average AUS/FLUS ROM for 15 studies was high in Indian practice, whereas the ROMs for FN/SFN and SM categories were within suggested ROMs by the Bethesda system from their meta-analysis, but different from their own practice (RR of FN/SFN nodules was low at 43.9% and ROM for FN/SFN was high at 72.0%).29

2.3 Republic of Korea

The Endocrine Pathology Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists conducted a nationwide survey on thyroid FNAC in Korea and published their results describing Korean practices for thyroid nodules and thyroid FNAC in 2017.21 They found that 60 (81%) out of 74 pathology laboratories in Korea used the Bethesda system as of 2012, which was a higher rate than in US practice reported in 2013 by the College of American Pathologists32 and 94% (34/36) in 2016.23 Proportions (average and range) of FNA samples in Korean practice were slightly high for AUS/FLUS at 9.7% (3.8%-19.8%) and very low for FN/SFN at 0.9% (0%-2.1%), which were reported in several previous studies from Korea.21, 33, 34 Average RRs of the six Bethesda categories were 14.3% (non-diagnostic), 2.4% (benign), 20.2% (AUS/FLUS), 43.7% (FN/SFN), 59.9% (SM) and 69.2% (malignant), respectively.21 The average ROMs for the six Bethesda categories were 46.5% (non-diagnostic), 16.5% (benign), 68.7% (AUS/FLUS), 30.2% (FN/SFN), 97.5% (SM) and 99.7% (malignant), respectively.21 Hong and Jung provided data from their practices (K. Kakudo, personal communication), as shown in Table 1. They found high ROMs (74.7% by Hong and 85.6% by Jung) for all resected nodules, similar with data from some members of the Working Group of Asian Thyroid FNA Cytology.

Although Korean clinicians follow the ATA clinical guidelines and recommend diagnostic lobectomy for patients with FN/SFN nodules, a low RR and high ROM for indeterminate categories were characteristic features in Korean practice. The high ROMs for AUS/FLUS nodules and SM nodules, together with the low RR and slightly high ROM for FN/SFN nodules, were confirmed in a study by Lee et al.33 Although Lee et al35 reported a higher RR for FN/SFN in 2014, their RRs for FN/SFN nodules were 81.3% (117/144) in the FNA group and 83.9% (172/205) in the core needle biopsy group. One of the most characteristic features of Korean clinical practice for thyroid nodules was the application of core needle biopsy.35 Twenty-one (27%) out of 74 pathology laboratories examined thyroid core needle biopsies,21 which are rare in other Asian countries. They reported no significant differences in ROMs for FN/SFN at resection between FNA and core needle biopsy groups, 48.8% (57/117) and 43.0% (74/172), respectively.35 Furthermore, the risk of neoplasia was not significantly different between the FNA and core needle biopsy groups, at 84.6% and 89.0%, respectively.35 Liquid based cytology was introduced for FNA preparation in 2010 and became a popular preparation in Korea.23 It was used by 44% institutions, and 22 (67%) out of 33 institutes used liquid based cytology combined with the conventional method in 2012 survey.23

2.4 Philippines

Abelardo summarised the current status of thyroid cytology in the Philippines, where there are only 10 practicing cytopathologists in the country.25 They analysed publications on cytological and histological correlation studies from the Philippines. Seven out of nine implemented the Bethesda system, and the Bethesda categories were generally accompanied by descriptive diagnoses. ROMs of AUS/FLUS in five reports ranged from 18.2 to 50% (average: 36.0%), which were higher than the implied ROM (5%-15%) by the Bethesda system and similar with those (average: 44.0%, range: 14.3%-75%) from other Asian countries. The average ROM for FN/SFN in four studies was 42.3% (range: 33.3%-50%), which was higher than the implied ROM (15%-30%) by the Bethesda system and in a similar range as those (average 44.0%, range: 20.9%-75%) from other Asian countries.25

High ROMs for both AUS/FLUS and FN/SFN were common in thyroid FNA practice in the Philippines.

2.5 Taiwan

Hang et al26 reported ROMs for thyroid FNAC at Taipei Veterans General Hospital.30 Their ROMs were 16.7% for non-diagnostic, 6.5% for benign, 41.7% for AUS/FLUS, 21.1% for FN/SFN, 75% for SM and 97.2% for malignant (Table 1). The ROM for AUS/FLUS was high, but that for FN/SFN nodules was within the implied ROM range (15%-30%) by the Bethesda system.

Huang et al36 analysed a health insurance database in Taiwan for 7700 newly-aspirated patients with thyroid nodules, of which 276 eventually developed thyroid cancer (ROM for all patients was 3.6%). They concluded that aspiration frequency, ultrasound frequency, older age, male sex, and endocrinology or otolaryngology subspecialties were associated with shorter time to thyroid cancer diagnosis. Risk stratification of patients for surgery is usually performed in clinical practice for patients with thyroid nodules in Taiwan.36

2.6 Thailand

Keelawat et al27 provided their thyroid FNA practice data from Chulalongkorn University, Thailand for 2010-2015 (n=2722).27, 37 Proportions of FNA samples for the six Bethesda categories were 47.6% for non-diagnostic, 40.8% for benign, 3.9% for AUS/FLUS, 2.6% for FN/SFN, 1.9% for SM and 3.2% for malignant, respectively. Their ROMs for the six Bethesda categories were 19.2% for non-diagnostic, 14.0% for benign, 37.9% for AUS/FLUS, 20.9% for FN/SFN, 81.5% for SM and 93.6% for malignant, respectively (Table 1). They further provided data from three medical centres in Thailand on resected nodules. Mean ROMs and range for the six Bethesda categories from the three centres were 21.7% (19.2%-22.6%) for non-diagnostic, 14.7% (14%-15.2%) for benign, 35.9% (32.9%-44.4%) for AUS/FLUS, 44.4% (20.9%-58.3%) for FN/SFN, 76.7% (70.4%-81.5%) and 92.6% (91.9%-93.6%) for malignant, respectively.27 Their ROM for AUS/FLUS was high, but that for FN/SFN nodules was only slightly high. They reported that the Bethesda system is the most widely accepted reporting system but aspirates with cystic fluid only were considered as benign by some readers in Thailand.27

3 THYROID FNAC IN ASIA

There are two types of clinical practice and reporting systems for thyroid FNAC of thyroid nodules in Asian countries. The majority of Asian countries have established their own guidelines for the management of thyroid nodules/cancer and these national guidelines often endorse the use of ATA guidelines and the Bethesda system.21-30 Japan, however, has developed its own clinical guidelines for the treatment of thyroid nodules. The Japan Thyroid Association (JTA) guidelines for thyroid nodule includes the national reporting system (the Japanese system) for thyroid FNAC.16 The Japanese Society of Thyroid Surgeons/Japanese Association of Endocrine Surgeons emphasises conservative management for low-risk thyroid carcinomas.38, 39 Recently Bychkov et al30 summarised cytological and histological correlation studies from six institutes in five Asian countries that follow the Bethesda system, and they found significant deviations in ROMs compared with western practice. Table 1 is a summary of ROMs for each Bethesda category obtained from the six institutes. ROMs for Bethesda category III (AUS/FLUS), Bethesda category IV (FN/SFN) and Bethesda category V (SM) varied widely among the six institutes. ROMs for AUS/FLUS were average: 44.0% (range: 14.3%-75.0%), ROMs for FN/SFN were average: 44.0% (range: 20.9%-73.3%) and ROMs for SM were average: 87.4% (range: 75.0%-94.1%), but were all higher than implied ROMs by the Bethesda system (5%-15% for AUS/FLUS, 15%-30% for FN/SFN and 60%-75% for SM) and actual ROMs, 14% (range; 6%-48%) for AUS/FLUS, 25% (14%-34%) for FN/SFN and 70% (53%-97%) for SM from a meta-analysis based on eight (one Asian, one European and six American) studies by Bongiovanni et al.9 There was one exception by Satoh et al,24 who reported 14.3% for AUS/FLUS and 26.6% for FN/SFN, which were within the range estimated by the Bethesda system.

4 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS BETWEEN AUS/FLUS AND SM CATEGORIES, AND STRICTER CRITERIA FOR PTC TYPE NUCLEAR FEATURES IN ASIAN PRACTICE

Satoh et al24 analysed 1600 FNAs examined at Yamashita Thyroid Hospital, Japan using the Bethesda system. Their RRs were 16.5% (non-diagnostic), 14.2% (benign), 27.5% (AUS/FLUS), 55.2% (FN/SFN), 75% (SM) and 92.6% (malignant), and their ROMs were 20.6% (non-diagnostic), 12.4% (benign), 14.9% (AUS/FLUS), 24.7% (FN/SFN), 92.3% (SM) and 100% (malignant), respectively (Table 2).24 The ROMs for AUS/FLUS and FN/SFN were consistent with ROMs implied by the Bethesda system.24

| Cytological diagnosis | Non-diagnostic | Benign | AUS/FLUS | FN/SFN | SM | Malignant | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNA sample number, n (%) | 382 (23.9) | 626 (39.1) | 171 (10.7) | 154 (9.6) | 52 (3.3) | 215 (13.4) | 1600 (100) |

| Surgically treated nodules, n (%) | 63 (16.5) | 89 (14.2) | 47 (27.5) | 85 (55.2) | 39 (75) | 199 (92.6) | 522 (32.6) |

| Malignant at resection, n | 13 | 11 | 7 | 21 | 35 | 199 | 287 |

| ROM at histology, % | 20.6 | 12.4 | 14.9 | 24.7 | 92.3 | 100.0 | 55.0 |

| Adjusted ROM, % (n)a | 34.9 (22/63/187)b | 87.0 (20/23/36)b |

- AUS/FLUS, atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance; FN/SFN, follicular neoplasm/suspicious for follicular neoplasm; SM, suspicious for malignancy; FNA, fine-needle aspiration.

- a ROM when 16 cases with equivocal papillary thyroid carcinoma type nuclear features were removed from SM and reclassified in AUS/FLUS.

- b Malignant/resected nodules/total FNAs.

Their analysis provides reasons as to why the ROMs for indeterminate categories vary widely among different centres. A reason could be the difficulty in classifying cases with worrisome PTC type nuclear features (nuclear atypia that cannot exclude PTC vs suspicion of PTC type malignancy, but not conclusive for malignancy).6, 10 If more cases are classified in the SM category, lower ROMs may be obtained for AUS/FLUS, similar to Satoh's practice. If they were classified in AUS/FLUS, a higher ROM for AUS/FLUS could be achieved.18 As shown in the last row of Table 2, when 16 cases with equivocal PTC type nuclear features were removed from SM and reclassified in AUS/FLUS, the RR of AUS/FLUS increased to 33.7% and the ROM of AUS/FLUS to 34.9%, higher than the ROM (5%-15%) implied by the Bethesda system, but within the range (34.4%-75%) of other five Asian practices in Table 1. From this observation, it may be reasonable to assume that the majority of cases with incomplete PTC type nuclear features are categorised in AUS/FLUS (stricter criteria for PTC type nuclear features) in most Asian practice, but more often classified in the SM category in western practice, which may be an explanation for the high actual ROMs for AUS/FLUS in Asian practice.

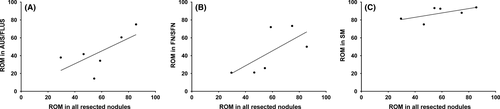

5 PREVALENCE OF THYROID CANCER

Another factor that may impact ROMs is the prevalence of disease in the given patient cohort. Although exact disease prevalence at each institution is not known, we can assume the prevalence based on the ROMs for all resected nodules. Correlations among ROMs of three indeterminate (AUS/FLUS, FN/SFN and SM) categories and ROMs of all resected nodules in six Asian countries are shown in Figure 1. The scatter plots indicate a positive trend. Lower ROMs for Bethesda categories are found in practices with lower ROMs for all resected nodules, while higher ROMs for Bethesda categories are found in practices with higher ROMs for all resected nodules (Figure 1). As cytopathologists or pathologists in these six Asian institutes were practicing in tertiary referral hospitals or thyroid cancer centres, the prevalence of thyroid cancer may be higher than at other community hospitals, and pathologists practicing in high prevalence populations may adopt the diagnostic criteria set for confirming malignancy. This adaptation of diagnostic criteria for malignancy may occur in Asian practice because the disease prevalence is high; as demonstrated by high ROMs for all resected nodules (average: 60.4%, range: 29.5%-85.6%; Table 1). These ROMs were higher than reported ROMs, average 31.3% (range: 20.8%-53.4%), for all resected nodules in seven western studies in the meta-analysis by Bongiovanni et al.9 The current authors speculate that most Asian cytopathologists, who are practicing in populations with a high prevalence of PTC, may employ stricter diagnostic criteria for PTC-type nuclear features. As significant observer variability in evaluation of PTC-type nuclear features in histological diagnosis of encapsulated follicular pattern tumours was reported between American and Japanese pathologists,40 and between American and Korean pathologists,41 differences may also occur in cytological diagnosis between western and Asian pathologists. This is one hypothesis as to why actual ROMs for indeterminate categories in Asia were higher than the implied ROMs by the Bethesda system.

6 FNAC HAS ESSENTIAL ROLES IN ACTIVE SURVEILLANCE OF PATIENTS WITH INDETERMINATE THYROID NODULES

Thyroid FNAC in Japan serves two different functions. The first is to confirm malignancy in patients with high risk or suspicious clinical features. The second is to assign the low-risk patients to three clinical management groups: (1) cytologically malignant nodules to surgical treatment, (2) indeterminate nodules to undergo further risk stratification (active surveillance) and (3) benign nodules to clinical follow-up after ruling out malignancy. The second function of FNAC is more important in clinical practice because the majority of patients with thyroid nodules exhibit low-risk or benign clinical characteristics. We agree with an excellent conclusion by Sheffield et al11 that the only truly diagnostic use of preoperative FNA is to rule out cancer in a low-risk patient, and patients with benign or low-risk clinical findings may be confidently followed after ruling out malignancy with FNAC. Diagnostic surgery is not indicated for patients with FN/SFN nodules when patients have benign clinical findings according to the JTA guidelines, and patients with FN/SFN nodules are actively observed until any suspicious findings appear. Consequently, active surveillance, common practice in Asia, for patients with cytological FN/SFN nodules establishes a low RR compared with in western practice. Moreover, it establishes not only low RRs but also higher ROMs for surgically-treated FN/SFN nodules with suspicious clinical findings as reported by several Asian studies introduced in this paper.8, 10, 21, 24, 25, 28, 29, 31, 33, 34, 42 The authors believe that this strategy is key in reducing overtreatment of borderline/precursor thyroid tumours and low-risk thyroid carcinomas, which are usually benign in other clinical tests.

7 HOW TO HANDLE PATIENTS WITH INDETERMINATE THYROID NODULES ACCORDING TO THE JTA CLINICAL GUIDELINES

Sugino et al42 examined how to triage patients with thyroid nodules for surgery and how to follow patients at Ito Hospital, Japan. Their detailed explanations were based on the JTA clinical guidelines on indeterminate thyroid nodules, in which patients with suspicious features are advised to have surgery and those with benign clinical findings usually undergo active surveillance until any suspicious features are detected. Surgery is not decided upon by cytological analysis alone for those with benign clinical findings in Japan.24, 43 Missing malignancy is carefully prevented by close follow-up of the patient, and long clinical follow-up of patients is an efficient strategy and possible diagnostic gold standard to establish the benign diagnosis. Patients who do not have thyroid surgery are clinically followed at an interval of 6-12 months. An ultrasound examination is routinely performed at each follow-up visit and FNAC is performed if follicular tumour or cancer is suspected by ultrasound findings. The indications for thyroid surgery for patients with tests not indicative of malignancy are: goitres of more than 5 cm in diameter or goitres that extend into the mediastinum and induce symptoms due to compression.42 By contrast, diagnostic surgery is recommended for all patients with FN/SFN nodules in the previous 2009 ATA guidelines1 and in the first edition of the Bethesda system,4, 5 even for patients with benign clinical findings, which is different from the JTA clinical guidelines.16, 42, 43

8 HANDLING OF NIFTP IN ASIAN PRACTICE

Regarding NIFTP reclassification, the ATA task force concluded that the advent of NIFTP did not significantly change the 2015 ATA guidelines other than by the proposed name change.44 It further added that the proposed reclassification from carcinoma to borderline/precursor tumour should not be interpreted as supporting a non-surgical approach to NIFTPs, as accurate preoperative identification of NIFTP has not yet been demonstrated.44 This is a very different conclusion from that of the JTA clinical guidelines based on the Asian way of thinking and logic, and the authors of this opinion paper believe that active surveillance (non-surgical approach) for patients with NIFTP or indeterminate nodules is the best choice for the patient. We believe surveillance is sufficient to prevent missing lethal cancers because long term follow-up of patients not only prevents overtreatment but also confirms the benign diagnosis. Diagnostic lobectomy for FN/SFN nodules increases the risk of treatment-related complications, which should be avoided, and Conzo et al45 reported that 15.1% of 1379 patients treated with thyroidectomy for FN/SFN nodules in 26 Italian hospitals had surgery-related complications. Do not harm patients is the first and most important element in Asian clinical practice, similarly emphasised in western practice.17, 46-48

9 PROGNOSIS OF THYROID CARCINOMAS IN INDETERMINATE CATEGORIES

VanderLaan et al49 reported that malignant FNA diagnoses identify higher risk PTCs, whereas AUS/FLUS diagnoses identify low-risk PTCs, mostly follicular variant PTCs. Rago et al50 from Italy concluded that thyroid carcinomas in Thy 3 (equal to AUS/FLUS + FN/SFN categories) had better outcomes than those in the Thy 5 category. Liu et al51 from the USA concluded that the Bethesda cytological categories successfully stratify patients based on their observation that recurrence, distant metastases and death increased as cytology progressed from AUS/FLUS to SM to malignant categories. Evranos et al52 from Turkey reported that SM or malignant cytological diagnoses were more often given to aggressive variant PTC (92.0%) and conventional PTC (56.6%), but less frequently to follicular variant PTC (24.3%). However, the authors of this article attribute all these observations and conclusions to the fact that significant numbers of borderline/precursor tumours were classified in the AUS/FLUS, FN/SFN and SM categories, and that they were included as malignant tumours. Contamination of series of carcinoma by borderline or indolent tumours significantly impacts on prognostic analyses because borderline tumours were categorised as malignant tumours before 2017 when the fourth edition World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs incorporated a new chapter of borderline tumours (uncertain malignant potential [UMP] and NIFTP) in the thyroid tumour classification (Table 3).53, 24, 55-57 This hypothesis was further supported by recent NIFTP studies that report that in some geographic areas of the world 10%-30% of newly diagnosed thyroid carcinomas could be re-designated as NIFTP, and significant numbers of NIFTPs were classified in the indeterminate cytological categories.58-68

| 2 | Hyalinising trabecular tumour |

| 2A | Other encapsulated follicular patterned thyroid tumours |

| 2A-1 | Uncertain malignant potential |

| 2A-1-1 | Follicular tumour of uncertain malignant potential |

| 2A-1-2 | Well differentiated tumour of uncertain malignant potential |

| 2A-2 | Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features |

However, the improved prognosis of thyroid carcinomas in indeterminate cytological categories reported in western practice was not confirmed in a study from Asia. In the study by Sugino et al,42 2719 (7.5%) patients with indeterminate thyroid nodules (both indeterminate A and indeterminate B in the Japanese system,16, 43 which are equivalent to AUS/FLUS and FN/SFN in the Bethesda system) were examined. Histological diagnoses of primary thyroid tumours were available for 1049 out of 2719 indeterminate nodules (RR: 38.6%). There were 472 malignant histological diagnoses (235 PTCs, 218 FTCs, 8 MTCs and 19 others) and the ROM was 45.0%. Sugino et al42 found that follicular variant PTC was not the major histological type, and the prognosis of patients with PTC and FTC in indeterminate categories was not different. The authors of this article conclude that these observations in Sugino et al's patient series42 were due to different methods of handling of borderline tumours and low-risk carcinoma. A significant proportion of malignancies in indeterminate categories in western patient series were contaminated with biologically benign borderline tumours because diagnostic surgical excision is the long-established standard of care for the management of FN/SFN nodules recommended by western guidelines and the first edition Bethesda system.1-5 However, this did not occur in Sugino et al's patient series42 because significant numbers of borderline tumours were monitored via active surveillance as recommended by the JTA guidelines, but was instead confirmed in a patient series from Kuma Hospital analysed by Hirokawa et al.22

10 ACTIVE SURVEILLANCE AND RESCUE SURGERY AT KUMA HOSPITAL

Hirokawa et al examined histological outcomes of their patients with thyroid nodules who underwent FNAC at Kuma Hospital, Kobe, Japan.22 The cytological-histological correlation study, including biopsies for non-surgical cases, such as undifferentiated carcinomas and malignant lymphomas, is summarised in Table 4. Their RRs of non-diagnostic, benign, AUS/FLUS, FN/SFN, SM, malignant categories at 1 year after FNA diagnosis were 4.8%, 6.3%, 25.8%, 42.2%, 57.9% and 68.3%, respectively. The RRs at 5 years after FNA diagnosis increased to 5.8%, 8.9%, 28.1%, 51.6%, 57.9% and 70.0%, respectively. Rescue surgeries between 2 and 5 years under active surveillance were indicated more for patients in non-diagnostic (21.4% increase), benign (41.0% increase) or FN/SFN (22.3% increase) categories than those in AUS/FLUS (8.9% increase), SM (3.7% increase) or malignant (2.5% increase) categories. Note that a significant number of patients with malignant FNAs were not treated with surgery because Kuma Hospital offers two options to patients with low-risk (intrathyroidal, N0, M0 and less than 1 cm) papillary microcarcinoma (PMC), active surveillance or immediate surgery.47, 48, 69-74 Only patients who changed their mind and wished to have their nodules removed or nodules with suspicious clinical features (more than 3 mm tumour size increase, new lymph node enlargement or suspicious feature on ultrasound) underwent rescue surgery after more than 1 year of active surveillance. Ninety-eight patients with PMC underwent immediate surgery within 1 year, and 16 patients dropped out from active surveillance and selected rescue surgery between 2 and 5 years. As a result, PMCs comprised only 9.8% (114/1180) of all malignant nodules in this cohort, a very small proportion, different from other patient series where nearly half of surgically-treated PTC was microcarcinoma.8, 15, 75-77

| Bethesda category | Cases, n (%) | Surgeries, n (RR, %) | Histological types at resection within 1 y (n) | ROM at 1 y, % | Number of surgeries and proportion (%) between 2 and 5 y | Histological types at resection between 2 and 5 y | ROM in 200 rescue surgeries between 2 and 5 y, % | ROM at 5 y, % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign (n) | Borderline (n) | Malignant (n) | Benign (n) | Borderline (n) | Malignant (n) | |||||||

| I | 585 (7.5) | 28 (4.8) | HN (10), FA (4), BD (3) | 0 (0%) | PTC (10), FTC (1) | 39.3 (11/28) | 6 (3.0) | HN (3), BD (1) | PTC (1), ML (1) | 33.3 (2/6) | 38.2 (13/34) | |

| II | 5156 (66.3) | 324 (6.3) | HN (177), FA (34), BD (10), HT (9) | FT-UMP (12), WDT-UMP (1) | PTC (68), FTC (9), ML (1), MTC (3) | 25.0 (81/324) | 133 (66.5) | HN (71), FA (23), BD (3), HT (3) | FT-UMP (6), WDT-UMP (1) | PTC (21), FTC (2), ML (3) | 19.5 (26/133) | 23.4 (107/457) |

| III | 306 (3.9) | 79 (25.8) | HN (14), FA (6), HT (2) | FT-UMP (3), WDT-UMP (6), NIFTP (1) | PTC (35), FTC (5), ML (5), MTC (1), PDC (1) | 60.8 (47/79) | 7 (3.5) | HN (1) | WDT-UMP (1), NIFTP (1) | PTC (4) | 57.1 (4/7) | 59.3 (51/86) |

| IV | 308 (4.0) | 130 (42.2) | HN (18), FA (63), HT(1) | FT-UMP (10), WDT-UMP (4) | PTC (6), FTC (24), PDC (4) | 26.2 (34/130) | 29 (14.5) | HN (2), FA (18) | FT-UMP (3) | FTC (6) | 20.7 (6/29) | 25.2 (40/159) |

| V | 140 (1.8) | 81 (57.9) | 0 | HTA (1) | PTC (70), FTC (1), ML (8), UC (1) | 98.8 (80/81) | 3 (1.5) | 0 | HTA (1) | PTC (2) | 66.7 (2/3) | 97.6 (82/84) |

| VI | 1275 (16.4) | 871 (68.3) | HN (1) | WDT-UMP (4), NIFTP (1) | PTC (843), FTC (2), ML (5), MTC (4), PDC (3), SCC (1), UC (7) | 99.3 (865/871) | 22 (11) | 0 | 0 | PTC (22) | 100 (22/22) | 99.3 (887/893) |

| Total | 7775 (100) | 1513 (19.5) | 352 | Rate of borderline tumours in malignancy: 3.8% (43/1118) | 1118 | 73.9 (1118/1513) | 200 (100) | 125 | Rate of borderline tumours in malignancy: 21.0% (13/62) | 62 | 31 (62/200) | 68.9 (1180/1713) |

- RR, resection rate; ROM, risk of malignancy; HN, hyperplastic nodule; FA, follicular adenoma; BD, Basedow/Graves’ hyperthyroid disease; HT, Hashimoto thyroiditis; HTA, hyalinising trabecular adenoma/tumour; WDT-UMP, well differentiated tumour of uncertain malignant potential; NIFTP, non-invasive follicular neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features; FT-UMP, follicular tumour of uncertain malignant potential; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; ML, malignant lymphoma; MTC, medullary (C-cell) thyroid carcinoma; PDC, poorly differentiated carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma and UC, undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma.

However, PMC is not the only biologically indolent thyroid tumour and indeterminate thyroid nodules larger than 1 cm with benign clinical findings are also actively surveyed, as recommended by the JTA clinical guidelines.16, 17, 22, 24, 42, 43, 46 This active surveillance for indeterminate nodules successfully spare borderline tumours immediate surgery. It was shown in Kuma Hospital practice where a higher rate (21%, 13/62) of borderline tumours was found in the rescue surgery group compared with 3.8% (43/1117) in immediate surgery group (Table 4), which was statistically different (P<.0001, χ2=34.356). It was further confirmed in different ROMs of all resected nodules between immediate surgery and rescue surgery groups, which were statistically different (73.9% [1118/1513] vs 31.0% [62/200]; P<.0001, χ2=149.64). In rescue surgeries for 29 FN/SFN nodules, there were six FTCs and no PTC (ROM was 20.7% [6/29]), and they were treated successfully without increased morbidity and mortality. One more important observation is that there was no thyroid cancer death in the rescue surgery group. We report here that there were no diagnostic misses of lethal thyroid cancer in this active surveillance programme for low-risk PMC and indeterminate nodules with benign clinical findings, although there were two cases of undifferentiated cancer and two cases of malignant lymphoma in malignant FNAs without histological confirmation that were neither treated with surgery nor on active surveillance.

11 HOW TO IMPROVE PERFORMANCE WITH LIMITED RESOURCES

Pre-surgical confirmation of malignancy with other clinical tests in cytologically malignant or SM nodules is a common practice in Japan, and Japanese clinicians believe it is essential for minimising false-positive diagnoses. This strategy also allows us to provide a higher priority to patients with large (T2 and T3) carcinomas, advanced stage (Stage III and IV) carcinomas and high-risk (aggressive variants PTC, angio-invasive FTC and poorly differentiated carcinoma) carcinomas for surgery, and quickly provide for those who need immediate surgical treatment. It was demonstrated at Kuma Hospital, as shown in Table 4, that high-risk malignancies (poorly differentiated carcinomas, undifferentiated cancers, medullary thyroid carcinomas and malignant lymphomas) were concentrated in the immediate surgery group. High ROMs for all surgically-treated nodules may also be related with this Asian clinical practice. The ROM was 73.8% (1117/1513) for the immediate surgery group at Kuma Hospital and 55.0% by Satoh in Japanese practice, 85.6% by Jung and 74.7% by Hong in Korea, 58.8% by Jain in India and 86.0% by Zhu and 85.1% by Liu in China, all of which were much higher than actual ROMs (average: 31.3%, range: 20.8%-53.4%) for all resected nodules in eight western series from the meta-analysis by Bongiovanni et al.9 Consequently, a lower priority for immediate surgery is given to patients with indeterminate nodules, intrathyroid (T1, Ex0, N0, M0) low-risk carcinomas (PTCs and FTCs) or borderline tumours that are actively surveyed. The active surveillance on indeterminate nodules in Asian practice may also be the underlining reason as to why rates of NIFTP and other borderline tumours were low in surgical follow-up cases.17, 20, 22, 24, 30 As borderline tumours (hyalinising trabecular adenoma/tumour, NIFTP, WDT-UMP and FT-UMP in Table 3)43 usually do not exhibit any malignant ultrasound features,17, 62, 68 they are more often watched in Asian practice, differing from clinical management recommended by the ATA guidelines, which classifies NIFTP as requiring surgery.44 Borderline tumours were rarely found: 4.7% of malignancy over 5 years in Kuma Hospital (Table 4). However, rescue surgery was performed more for borderline tumours (21.0% of malignancies) during active surveillance (Table 4). This increased incidence of borderline tumours in the rescue surgery group between 2 and 5 years after FNA was consistent with our hypothesis that the majority of borderline tumours and low-risk carcinomas were spared immediate surgery in Asian practice. The authors believe that immediate surgical resection is not necessary and should be avoided because borderline/precursor thyroid tumours do not harm patients if they are left untreated, as demonstrated at Kuma Hospital experience, an example of evidence-based treatment de-escalation for biologically indolent tumours. However, it is imperative that patients and clinicians be properly educated, patients be followed for life long, and appropriate tools be identified to implement the strategy.74

12 RISK STRATIFICATION OF PATIENTS WITH INDETERMINATE NODULES AND ACTIVE SURVEILLANCE OF PATIENTS WITH INDETERMINATE NODULES

As the majority of cases with indeterminate cytology are benign or borderline tumours, and the majority of thyroid carcinomas in indeterminate categories were low-risk,49-52 clinical follow-up of these nodules is one method recommended by the JTA clinical guidelines as long as they have benign clinical features.16, 17, 45

Proper risk stratification of indeterminate thyroid nodules is of paramount importance in reducing overtreatment of indolent thyroid tumours. The current authors believe that this strategy in Asian practice is the cause of actual ROMs for indeterminate nodules (AUS/FLUS, FN/SFN and SM) being high, and RRs of AUS/FLUS and FN/SFN being low. In the 2015 ATA guidelines, risk stratification of FN/SFN nodules was partly incorporated in recommendation 16.3 Diagnostic surgical excision was stated as the long-established standard of care for the management of FN/SFN nodules. However, after consideration of clinical and sonographic features, molecular testing may be used to supplement malignancy risk assessment data in lieu of proceeding directly with surgery.3 As the 2015 ATA guidelines provide molecular testing for FN/SFN nodules as an option, clinical follow-up is one choice when the nodules have benign molecular features. Surgery on patients with FN/SFN nodules is decided after confirmation of suspicious or malignant features with clinical, sonographic or molecular tests, which is a significant revision in the 2015 ATA guidelines.3 Such trends towards thoughtful evidence-based treatment de-escalation paradigms was emphasised by Valderrabano and McIver,78 and by Kovatch et al79 in western practice to reflect better risk stratification of thyroid cancer, which is a common practice in Asia.16, 17, 22, 24, 42, 43, 46 Of the proposed modifications and updates for the second edition of the Bethesda system, application of molecular tests, clinicoradiological risk stratification, and a multidisciplinary team approach for both AUS/FLUS and FN/SFN nodules were emphasised.80 This looks like the active surveillance recommended by the JTA clinical guidelines, which is common practice in Asia and Japan.

13 CONCLUSION

Low-risk thyroid carcinoma and borderline/precursor tumours are not rare in clinical practice for patients with thyroid nodules. These indolent thyroid tumours are considered to require surgery in western practice and composed a significant proportion of indeterminate nodules on histology. However, conservative clinical management, such as active surveillance without surgical intervention, for such tumours is favoured in Asia, these borderline tumours are rare on histology in Asian practice. As active surveillance for patients with indeterminate nodules significantly reduced surgical treatment of borderline tumours, low RRs and high ROMs for indeterminate nodules were achieved in Asian practice. This clinical management of thyroid nodules in Asian practice is important to reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment of indolent thyroid tumours. Unnecessary treatment-related complications in patients who may not require treatment are therefore reduced, which is an indispensable factor for Asian practice.