Empowerment evaluation: Key methodology aspects from participatory research and intervention with Roma girls

Abstract

Empowerment evaluation (EE) is an especially useful tool that enables people to be involved in both individual and group transformation processes, in particular in contexts characterized by social inequality. By using a participatory approach, this methodological article analyses an Empowerment Evaluation experience within the European RoMoMatteR project. This project, which focuses on the notion of reproductive justice, has involved a group of Roma girls from Alicante (Spain), in a context characterized by discrimination based on ethnicity, gender and age, as well as by structural determinants such as social exclusion. The main research objective has been to analyse the relevance of the methodology designed to assess how project participants have developed a sense of autonomy and the acquisition of socio-cultural resources as assets for their future life choices. Therefore, the study design has followed the model proposed by Fetterman for Empowerment Evaluation: establishing a mission to be assessed, participatory diagnosis of the current status and finally planning for the future to start the desired change. Fetterman's model was adapted by designing and organizing participatory workshops with the girls involved in the project. The results confirm the relevance of the methodological proposal of the workshops to engage aspects of empowerment. The findings also allow to detect the empowerment of the Roma girls especially in two areas of the project: reaching the proposed objectives and the methodology used to register significant information. In the first case, the results show that Roma girls' establish a critical perspective on the idea of reproductive justice, and related to this, the activation of proactive behaviours linked to the acquisition of socio-cultural resources in the development of visions of their personal futures. In the second case, the Roma girls have also shown empowerment in decision-making on technical aspects, methodological design and taking action aimed at the collective construction of useful information in the project.

INTRODUCTION

This study is based on a Participatory Action Research process with Roma girls (self-identified as Kale/gypsies) in Alicante, Spain. The experience is considered within the framework of the European project ‘RoMOMatteR: Empowering Roma Girls' Mattering through Reproductive Justice’. The project is based on transforming social and cultural resources when creating life plans and decisions of young Roma girls (aged 10 to 14 years old) within a reproductive justice approach. The concept of reproductive justice frames this project and is defined as women's autonomy regarding their reproductive health, the decision to have children or not and to bring them up in safe, healthy and sustainable environments and respected in culture and identity. This is a basic right that refers to making decisions on one's own life and demands that society guarantees these rights from the political, social and economic spheres (ACRJ, 2005; Luna & Luker, 2013).

As a strategy of this study, the aim of Participatory Action Research (PAR) was to promote transformation actions that allow the people involved to have active roles. This enables participating populations, in this case Roma girls (we use the term girls, translated from the Spanish word ‘chicas’ as the same one used by the participants themselves), to be co-producers of knowledge and transformers of their own lives. Furthermore, it allows cognitive and operational resources to be adopted through PAR, as shown by the results of previous research with children or adolescents (Chen et al., 2010; Shamrova et al., 2017). Therefore, one of the notable features in the development applied to PAR is its transformative potential, especially when regarding working in contexts of poverty and discrimination. These privative contexts determine access to resources, social opportunities and power, especially for women who belong to an ethnic community that has historically been discriminated against (Eklund et al., 2019; Ryder, 2015). In this sense, the transformative process alongside PAR does not pursue an acritical integration of protagonist populations in the hegemonic values or cultures, but instead seeks to develop an emancipatory potential according to the ways of life that the participants view as desirable.

Participatory Action Research originates in approaches that challenge traditional research in which populations play a passive role as the object of study in order to place the community's own knowledge at the centre of the scientific project (Fals Borda, 1993; Rodríguez-Villasante, 2002). Research with a PAR approach aimed at women contribute to reducing gender inequalities, as they involve analysis, reflection and action taking into account the context of influence on women both to create knowledge and to promote training and provision of tools to generate changes in their lives (Brinton-Lykes & Hershberg, 2012). Studies applying participatory methodologies conducted in communities have made it possible to explore and assess women's perceptions on their current situation and their felt needs in relation to accessing positions of power, community health (Ponic & Frisby, 2010) sexual and reproductive health (Khalesi et al., 2020), mental health (Raanaas et al., 2020) or accessing resources and social opportunities, among other issues of interest to women, in order to generate processes of social transformation (Aziz et al., 2011).

The different methodological proposals that the Empowerment Evaluation (EE) approach provide are especially useful in PAR (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Powers & Tiffany, 2006). A first approach to the widely used notion of EE is that by David Fetterman (1994, 1996), as he conceptualized this strategy as the use of evaluation concepts, techniques or findings of a process in order to increase the control and self-determination of the subjects, with the aim of improving their lives. Based on this definition, subsequent developments have added elements that specify the requirements and approaches of EE. The approach by Wandersman et al. is especially relevant, as (2005) it influences the idea that EE tools should assess the implementation and self-assessment of projects (i.e. interventions) and comprise a transversal element when planning and managing them. Therefore, the underlying goal of the EE strategies is to provide conceptual and methodological tools that allow the participants to self-assess both themselves and the ability of the project to empower them in relation to the topic being addressed. In this sense, EE is aligned with what Lub (2015) calls an emancipatory approach to evaluation. This involves a series of paradigmatic principles aimed at applying the resulting information for empowering purposes.

The characteristic elements of EE are based on two main aspects. The first aspect is the emphasis made on considering competences and resources that the subjects can include to generate a process of change (Nitsch et al., 2013), based on the ability of deciding themselves about their lives and improving their well-being. The second aspect involves control that the team in charge of the intervention and participants have over the evaluation process (Fetterman, 2001; Rodríguez-Campos, 2012), both in terms of method and content. The group collectively makes decisions. The main role of the evaluators is to adapt and provide data logging matrices.

The reasons behind introducing EE in the framework of RoMoMatteR are: (a) its usefulness to transfer evaluation results to other similar contexts, as a result of the participation of the participant subjects; (b) its potential to generate actions that provide feedback on the project; and (c) the ability to adapt to the gradual evolution in the empowerment of Roma girls. Evidence on these three aspects (Wandersman et al., 2015) give EE a significant opportunity to provide a differential value regarding the traditional aspects in assessing community projects that often tend to serve the research itself, and not so much at the service of the target population, in this case, Roma girls, therefore, fostering new participatory cycles of action-reflection based on the results of the evaluation.

In an empowerment process with young women from ethnic minorities, as in this case, the starting point is usually characterized by situations of discrimination or stigmatization in which different axes of inequality, such as gender and ethnicity, interact with socio-political structural determinants as social inequality and poverty. It is especially necessary for the community to be aware of their own reality, of the factors that occur in their daily lives, and of the difficulties in exercising their endogenous potentialities and developing strategies. This issue is critical when working with a pre-adolescent or adolescent population, especially regarding girls, as is the case of RoMoMatteR. This age range is when they start to be more autonomous and it is a key period to develop their identity (Zimmerman et al., 2018), which is the ideal window for an intervention aimed at increasing control over the decisions that affect them and where they can determine their transition to the adult world. However, socialization processes must also be taken into account in order to understand their position in their neighbourhoods and their opportunities for development. Therefore, the evaluation option in EE is so important, as this approach not only provides knowledge on the reality of the groups of interest, but it also includes the life experience of the key subjects about the processes, contexts and structural elements related to facing these realities.

Therefore, EE's main aim was to empower subjects in the formulation of the problem and the way of assessing the solution. In line with this, designing the RoMoMatteR project, workshops and group sessions with the girls involved in the intervention is aligned with the principles that Wandersman et al. (2005) state to foster EE as shown in Table 1.

| 1. Improvement | RoMoMatteR is pragmatically aimed at transforming the key aspect of the population: Autonomous decisions on life projects. |

| 2. Community ownership | Girls have effectively exercised their right to make decisions in relation to the direction of the project and the evaluation process. |

| 3. Inclusion | The experience has involved a local alliance including many stakeholders involved in the matter at hand, including families, Roma associations and local institutions. |

| 4. Democratic participation | The results of the project have been coordinated from the horizontal participation of girls and the production of critical discourses in contexts of collective deliberation. |

| 5. Social justice | The project's explicit goal focuses on transforming social conditions and opportunities in terms of reproductive justice. |

| 6. Community knowledge | Roma girls have been recognized as experiential experts, capable of analysing their own problems with the help of facilitators and also capable of imagining lines of action to face said problems. |

| 7. Evidence-based strategies | The work dynamics have included references to tools that have previously been useful in other projects, adapting them to the local context and conditions. |

| 8. Capacity building | At the end of the project, the Roma girls indicated having a perception of greater control over decisions related to their life projects, although this is an aspect to be assessed in the medium–long term. |

| 9. Organizational learning | The project has been a learning opportunity in the ‘know-how’ of the groups and organizations involved in the project. |

| 10. Accountability | The project has fostered the development of a sense of mutual and interactive responsibility among those responsible for the project, the research team, the civic organizations involved, the team of facilitators and the girls themselves. |

- Source: Own elaboration based on the proposal by Wandersman et al. (2005).

As observed in Table 1, the conditions, context and assumptions of the RoMoMatteR project, as indicated in the ten principles, determine the viability of the EE proposal. Once the relevance of this exercise is justified, the specific aim of this article was to analyse the methodology used to assess how the participants, especially Roma girls and the community, have progressed towards their empowerment.

In accordance with the expressed objective, the article first approaches the description of the context in which RoMoMatteR is framed. The study design section details the methodological proposal of EE carried out in the PAR framework of the project, as well as designing workshops with the girls. The results section will analyse the information registered related to the effects of empowerment based on the designed methodological proposal. Finally, the discussion and conclusions discuss the contributions, scope, conditioning factors and limitations of the research in relation to empowering girls in particular and the EE approach in general.

METHODOLOGY: DESIGNING THE EE PROPOSAL

RoMoMatteR Alicante is a project carried out through Participatory Action Research (PAR) processes based on collaborative alliances between Roma girls and relevant people in their lives, for instance, families, civic organizations and public services, as well as other adults important for them.

The RoMoMatteR Alicante consortium is made up of members of the Roma community in Alicante, a Roma grassroot association called FAGA and the University of Alicante. Based on convenience sampling, and in line with the RoMoMatteR project requirements, 18 girls participated in the project, aged between 10 and 14 years, at school, self-identified as Roma (Kale, Spanish Roma, ‘gitanas’) and born in Spain. The girls were recruited from the work groups of FAGA and the community by the facilitators. All girls went through a selection process by means of an interview in order to identify whether they met the aforementioned inclusion criteria. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee at the University of Alicante (Exp. UA 2019 07 18).

In addition to the girls' participation, the design of PAR proposed to create several teams. These teams included three with different responsibilities that are highlighted due to their importance, although with a horizontal articulation in relational terms. The three groups involved people belonging to the Roma community and were: (a) research team including research members from the University of Alicante, who were in charge of supervising the project; (b) the team in charge of the intervention, including members of the academic team and those in charge of coordinating sessions and workshops with the girls; (c) the fieldwork team including people in charge of coordinating sessions and three adult Roma women with experience in community work who were involved in the project to act as facilitators in the activities and workshops with the girls. The women facilitators were selected by Roma associations, which were linked to the project. Their responsibility, together with technical/research assistants throughout the project, was to guide the workshops by creating a comfortable environment that encouraged the Roma girls to participate and debate actively, and to help them develop a leading role both in analysing their own reality and in generating ideas. It must be considered that people from the community participated in all these teams, that is, beyond the nomenclature, the project did not include any type of hierarchy among them, but rather corresponded to a division of work on a horizontal plane. Participation by the girls and facilitators was voluntary and not paid. Informed consent was obtained from the participants at the beginning of the project.

The fact that the fieldwork team is made up entirely of women related to the Roma community, as well Roma women and a female community technical manager, is precisely a distinctive feature of the RoMoMatteR project. Without this, it is not possible to understand the final configuration of the evaluation proposal. The women of reference from the Roma population of Alicante and various significant adults (fathers/mothers/grandmothers) for the girls have also been involved in the project. The network of family and neighbours are shown as relational spaces especially inclined to establish common communicative codes (Gamella et al., 2015). Therefore, the context required incorporating the perspective and communication codes of the Roma community of Alicante by means of the testimony of women of reference. Incorporating women of reference from the local community has been a strategic element to be able to debate aspects of early motherhood or reproductive justice in a normalized and conscious way in the intervention with the community.

The RoMoMatteR Alicante project fieldwork began in February 2020 with the capacitation of facilitators. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of interventions were suspended from March to June 2020 and took place in June and July 2020 when in-person group sessions were possible. However, the intervention continued in November and December 2020 with additional events till June 2021 (workshops based on the topics related to the needs expressed by the girls, their interests and proposals).

Study design

This study design uses the materials resulting from the EE workshops carried out in the RoMoMatteR Alicante. The project understands the development of autonomy and the acquisition of socio-cultural resources as desirable for girls for their life decisions in the future. For this reason, evaluation tools capable of both diagnosing the present situation and defining which key aspects should be fostered or avoided in order to achieve the desired future are relevant. In this sense, the methodological proposal for EE developed by Fetterman (2002) offers an ideal model for the framework of the project, which is specified in three steps or moments: (1) establish a mission in terms of the topics to be assessed; (2) review the current status, carrying out a quick participatory diagnosis capable of collecting positive and negative aspects related to the topic addressed and which can influence the possibility of success when reaching the desired change; and (3) planning for the future, which includes establishing which aspects should be taken into account if we want to start the desired change. These three steps are included in different contents of the two EE workshops carried out at the end of the RoMoMatteR project. The content and dynamics of the two EE workshops carried out are described in detail below.

EE workshop I: ‘The journey to your dream job’

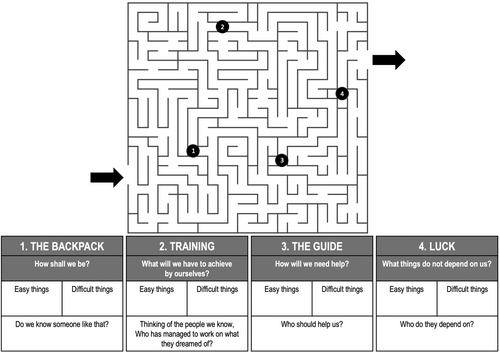

The first step in EE workshop I, the definition of the mission, resulted in the teams choosing a meaningful topic related to issues worked on in the project. The selected topic was labour expectations, with the title ‘The journey to your dream job’. The second step was to review the current participatory situation by identifying values and competencies that the girls had displayed in the project. The third step in the Fetterman model of EE involved planning for the future. In order to reach this final step, this workshop collectively assessed which aspects of the girls' daily lives could change and did they want to change, as well as which ones could not be changed or did not depend on them, even if they wanted to, therefore, requiring the intervention of other social stakeholders.

The metaphor of the labyrinth was used to guide the workshop as a way to elicit paths and difficulties that the girls can find in their journey to their desired professional future (Step 1). In line with this, the girls played a game to move forward in the labyrinth to pass a series of tests (questions). The questions were specifically designed to encourage participatory reflexivity of the girls on the different elements that, in this case, were based on their work expectations.

The four challenges (Step 2) were related with aspects related to empowerment. The first one, with the label ‘backpack’ required participants to collectively agree on personal traits that should be present in their personalities to move towards their desired professional future. Furthermore, they were asked to identify references, people they know who share these values. The second challenge was ‘training’, followed by a debate on achievements and skills needed for the process towards their desired professional future and additional aspects required to reach a consensus in terms of competences to be achieved from the characterization of professional references. The third was ‘the guide’, with the intention of understanding the needs of accompaniment, collaboration or help to pave their way towards their desired job, thus reflecting on identifying people or social stakeholders who can meet this function. Finally, the fourth challenge was called ‘luck’ and asked participants to list opportunities or threats, exogenous to the girls' capacity for action, with the possibility of them occurring throughout their journey towards their professional future. Furthermore, they were all asked to think as a group on the strategies to face all of the aforementioned, as well as social stakeholders on which these aspects would depend (Step 3). Figure 1 visually summarizes the first EE workshop proposal used with the girls.

EE workshop II: Participatory evaluation matrix and cycle reopening at the end of the project

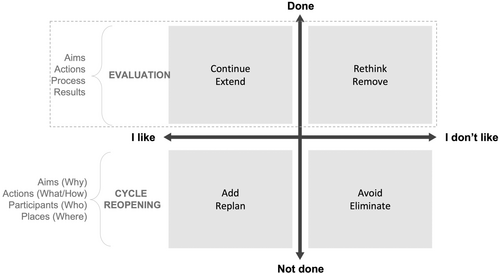

In the second workshop, the mission was based on assessing the scope of the project regarding goals, actions, processes and results. The second step was registered through the collective assessment in terms of approval or rejection of what was effectively carried out throughout the project. In line with PAR, the third step was based on identifying elements that could be included or avoided in new cycles of the project. The proposal developed in EE on these three steps has sought to generate valid learning for reflection and action from the evaluation exercise itself.

Two group dynamics were designed for the second workshop: one with facilitators and the other one with the girls. The workshop topics were: (a) what they liked and did not like about the project (I like – I don't like); and (b) matters that were included in the projects and were not included (Done – Not done). The objective was to assess the scope of the project in terms of goals, actions, processes and results (Step 1). The interaction between these two aspects in the dynamics has allowed 4 spaces for reflection and evaluation to be identified in relation to the project:

A first space, ‘I like—Done’ includes items assessed as positive in the project. In other words, actions carried out in the project that have been considered a success. Future cycles of reflection-action could delve into these initiatives more. A second space, with the label ‘I don't like—Done’, includes implemented actions that are not well-accepted, based on the subjects' assessment. The results of the participatory evaluation carried out in these first two spaces constitute step 2 of this EE workshop. Therefore, future actions or projects should eliminate or reconsider these initiatives. The third space, ‘I like—Not done’, includes aspects assessed by the participants as wishing they had been included in the project, but they were not. New activities should be designed in future projects based on what the girls have expressed, or reconsider the goals of the activities in the cycle that is finishing. Finally, ‘I don't like—Not done’. This space includes aspects, such as undesired actions, but they were not included in the project. In terms of planning future cycles of reflection-action, attention needs to be paid to guarantee they are effectively eliminated or not included. The girls' contributions in these last two spaces constitute step 3 of this second EE workshop.

The summarized graph shows the design of this matrix of participatory evaluation and the implications of opening new cycles included in Figure 2.

In both workshops, the group dynamic was carried out and coordinated in a fun environment by the facilitators. The procedure to collect and register primary information was conducted based on the contributions of the participating girls with cards designed to be filled in and placed, after reaching a collective consensus, on the different conceptual spaces proposed graphically in the sessions, and photographed for later analysis. In the same sense, discussions were also held with the team of facilitators in order to obtain a record during the session and practical exercises with the girls.

Table 2 shows a summary of what activities were included in both workshops and the integration in the EE methodological proposal.

| EE Workshops | Step 1: Establishing the evaluation mission | Step 2: Reviewing the current participatory situation | Step 3: Planning for the future |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workshop I: ‘The journey to your dream job’ | Assessing work and professional expectations of Roma girls | Identifying values and competences developed in the project. | Identifying vital issues with autonomous transformation capacity by the girls and aspects whose transformation depends on the intervention of external agents. |

| Workshop II: Participatory process evaluation matrix and cycle reopening at the end of the project | Assessing the scope of the project in terms of goals, actions, processes and results. | Approving or rejecting the actions involved in the intervention programme | Defining contents and strategies to be included or dismissed in new possible cycles of the project. |

- Source: Own source based on the model proposed by Fetterman (2002).

RESULTS

Both EE workshops in RoMoMatteR are framed within a sequence of sessions with the girls that consisted of 21 steps of group work. Including EE workshops in this sequence was in line with two essential objectives. Firstly, to reinforce the empowerment objective of the project. Second, register girls' assessments of their own progress, as well as the project's scope for the empowerment goal. The results of the EE in RoMoMatteR are explained as follows with an analytical outline on Fetterman's three-step model: establish the mission, review the current situation and plan for the future.

Regarding the first step, the mission sessions were arranged where the facilitators introduced different personalities likely to be people of reference, finally establishing aspects that should plan personal careers to reach the desired experiences, as well as what is present or absent in the project regarding these issues. It became clear in these workshops that there was a need to set a series of values and behaviour capable of promoting or maximizing autonomy in order to control one's own life. The girls agreed on the commitment to values already present in the group, such as a positive willingness towards challenges, strength or hope. Other aspects that should be fostered or worked on include perseverance in personal progress, full integration in academic and school dynamics, determination when faced with difficulties or the courage to face difficulties (see Table 3).

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| What has changed at school for you after RoMoMatteR? | I am empowered at school and I have defended my rights as a woman in games and so. (E06) |

| Now everything is easier, I have a taste of what studying is like. I wanted to drop out and it has helped me to not quit. (E07) | |

| I have become more ambitious with what I want for my future. (E09) | |

| How many things have changed in your life in the last 12 months | Many things, both positive and negative. I want to fulfil my dreams. (E04a) |

| My circle of friends and my expectations, I want to be a psychologist or a makeup artist. (E09) | |

| I have grown, I see things differently to when I was 7 or 8 years old. (E18) | |

| What skills did you learn at RoMoMatteR? | To have more knowledge about myself, my situation, to mature, to know what I want and I can be whatever I want to be. (E06) |

| To speak to people better and not be so embarrassed about speaking aloud with others. (E09) | |

| You have to work hard for your dreams, if you do not work hard nothing will come of it. (E10) | |

| Now I can do something and not give up. (E13) |

- Source: Own elaboration.

The second step of the EE model is to review positive and negative aspects related to the topic and the project itself. Based on the workshops conducted by the facilitators and the girls, among the positive results related to reproductive justice, elements emerge such as the fact that the project has boosted the girls' dreams, generating a critical perspective of reproductive justice, horizontality in exercising power by people linked to the intervention process and behaviours of involvement and proactivity related to the transformation process (see Table 3). From the Roma girls' perspective, the results show the importance of having an interrelation between empowerment, group identity and psychological well-being. In this sense, evaluations reveal they highly value group experiences and the elements that bind them together, as well as reinforcing cultural and ethnic identity as women in their approach. Examples of this are the girls' highly positive regard that the facilitators were Roma or identifying the high degree of affinity and harmony in internal coordination by the team of facilitators, while respecting and enhancing the knowledge of each one as an element of success.

In terms of taking stock of implementing the project, the appropriation of technical and methodological aspects by the fieldwork team and the girls stands out. Both perceived the excessive burden of registering information in relation to the intervention sessions as a limiting factor to favour the development of socio-cultural resources and autonomy to make decisions. Adapting registration tools, whose design was not participatory but elaborated by the external research team, generated a ‘laboratory effect’ in terms of the participant subjects. The perception of external scrutiny of the intervention activities was developed with an instrumental purpose external to the motivations and empowering purpose of the project, reducing spontaneity and time to dedicate to the endogenous goals of the group. As the girls indicated, the project has a fundamental purpose if it is possible ‘to talk without being judged’. This resulted in an intense debate on the role the girls have regarding the project goals, due to the conceptualization as subjects of the project or as objects of it, thus, as stakeholders with the capacity to influence the course of the project and its content or as mere beneficiaries of the actions planned in it. The debate was settled by prioritizing the life component of the participant subjects and subordinating the information registering tools. Therefore, the roles of the participating entities and people were redefined, including those belonging to the research team that had designed said instruments.

The fieldwork team and team in charge of the intervention, together with the girls, redesigned part of the activities of the sessions. Certain actions became part of the project, such as visits by women whose professional profiles or life experiences are inspirational for the girls; or storytelling workshops aimed at building a critical capacity in the future imaginary of the girls. In this same sense, planned outputs of the project were realigned and new ones were added, such as organizing plays with contents related to the theme of the project as they had not been foreseen in the project methodology.

Finally, the third step in the EE model entailed planning for the future, aimed at registering key information to be considered when working towards desired goals. In this area of socio-cultural resource development for their life projects, as well as the autonomy and the necessary individual initiatives that the girls understand as a condition for personal development, the Roma girls identified both success and risk factors in terms of planning for their future. In relation to the first aspect, the strong affective networks of both family and friends have been perceived as an endogenous factor for success. In this sense, a consistent network of informal supports is recognized as an essential asset for desired personal development. Yet if we observe the downside, factors that can inhibit the dynamics of empowerment were identified as having a double condition of discrimination as members of the Roma community of Alicante and as women, the lack of support and education resources from public institutions and society at their disposal, and their health context characterized by more disadvantaged indicators than those of men and the general population, which is seen as a unknown element to determine control over their life decisions. In order to face these challenges, the leading subjects highlighted a series of elements that would maximize the empowering impact on new project cycles or on continuing the project itself: the relevance of carrying out a rapid participatory diagnosis of the community in each place of intervention in order to adapt it to the social, economic and cultural conditions of each community; participatory design of the methodologies for the intervention sessions; the importance of the facilitators being members of the community; the concept of the intervention sessions as a reality away from school rules; the need for support after completing the intervention actions; or presenting and disseminating the project through its leading subjects in communities outside their own.

DISCUSSION

The analysis carried out has made it possible to verify the emergence of empowering attitudes and traits in the girls participating in the RoMoMatteR project. The new attributes refer mainly to being aware of reproductive justice and having a critical vision in relation to their life projects. Furthermore, to the claim of horizontality in exercising power among the people linked to the intervention process of the project, and the attitudes of involvement and proactivity in relation to the process of personal transformation. These are the main dimensions of the analysis subject to reflection in the discussion.

Applying EE within the underage population, in a social context marked by the deprivation of basic needs and high levels of structural racism, has been an adequate methodology to reformulate the initial proposals of a community intervention project. Furthermore, it has revealed the impacts on key aspects such as: the type of instruments provided to assess the project, the way of organizing the work sessions with the girls and their contents, the results or milestones expected from the project (development of artistic expressions and personal development instead of acts of a more political nature in the media and public events), as well as in other technical aspects, such as decisions about the times and places for the activities. The strategy has been shown to be of interest to avoid the imposition of academic interests over those of community organizations and the people participating in the intervention. Developing autonomy and acquiring socio-cultural resources has also been reached in terms of technical or methodological aspects of the project, therefore, creating a critical appropriation by the participant subjects, as has been the case of the critical positioning of the girls and the fieldwork team. The empowering effect of some mechanisms of project registration, or its leading role in designing the new implementation structure derived from the impact of COVID-19 have been questioned.

In this empowerment process, in terms of the specific evaluation area, fieldwork team has played a key role that has had a triple task, thus enabling different stakeholder involvement approaches (Fetterman, 2019). Firstly, sharing control and agenda of the evaluation alongside the team in charge of the intervention. Secondly, carrying out an essential role as critical companions for the girls in the self-assessment and, finally, as active subjects to build valid collective information by carrying out a self-assessment process in the EE workshops, with the aim of registering positions and evaluations from their role within the project. The latter has also made it possible to triangulate the evaluation results generated by the girls with the vision of the facilitators. The women from the fieldwork team, far from acting as external experts, have assumed a role of collaborators with the girls, taking into account that they knew their living situations and those of their families, from an empathetic position and in line with the cultural key aspects of the girls, their wishes and their way of seeing the world. The relationship these women have with the Roma community of Alicante have given them a privileged place within the project, although it is also very demanding. Their role has also included expressing the research team's goals when transferring them in order to make cultural appropriation possible by the girls. In this sense, an essential approach by the team of facilitators was to develop a critical perspective regarding the different stakeholders of the project. The girls considered the approaches by the facilitators highly valuable when problematizing the initial visions in relation to reproductive justice or their expectations for the future, and favouring the emergence of a critical discourse with them in relation to their ability for self-determination in the vital decisions that will lead them to adult life. In terms of their relationship with the research team, the facilitators and the team in charge of the intervention have made it possible to re-elaborate the predetermined methodological work tools and their use by the girls, with their essential contributions based on the results of the different sessions.

Therefore, these facilitators are important when they adopt the role of experiential experts or critical friends (Fetterman, 2001), as also reflected in other EE experiences (Fernández-Moral et al., 2015). This role enables to translate and contextualize the culture of methodology research and intervention approaches that, without the input from the facilitators and the team in charge of the intervention, would run the risk of being implemented mechanically, exogenously or without any meaning for participants.

The project has enabled to reinforce the meaning of community for the girls, understood within the terms established by Graig (2005). Therefore, this is a group of people that share a set of identity signs, geographical or territorial environment and common interests based on collective matters. The relation between the elements of empowerment, identity and wellness have been indicated in literature (Molix & Bettencourt, 2010; Tahir & Rana, 2013), with special relevance made in the context of ethnic minorities.

In terms of the methodology, a relevant fact of the EE has been the control the leading subjects have had in the intervention process regarding technical decisions, thus confirming the proposals by authors such as Fetterman or Rodriguez-Campos who address empowerment in the evaluation as a control over the aims pursued by the project, but also control over the methodology of the project itself. In this sense, the results would also reinforce the idea previously indicated by Wandersman et al. (2005), considering EE not as an additional resource in the measurement of projects, but as an element of reflection that has a transversal effect on the planning and implementation of community intervention processes. Thus, in * RoMoMatteR, when conveying the girls' preferences, the fieldwork team has questioned the relevance of certain procedures, registration tools or designs for the implementation of actions due to their lack of adaptation or their limited capacity to generate critical empowerment dynamics. This circumstance has led to debates on power asymmetries in decisions related to the information construction process. Concepts, such as positionality and reflexivity, central to the epistemology of projects of this nature (Fremlova, 2018; Silverman, 2018), and which place the importance of the co-production of knowledge at the centre of the discussion (Ryder, 2015), were critically considered. These debates enabled a self-examination of knowledge production, which was especially important for non-Roma actors, based on three essential aspects: the objective of the project, the tools and methodologies, and the nature of the relationships between the research subject and the object/subject researched. The result was an agreed readaptation, through transversal synergies between different stakeholders, of the different registration materials and tools while expressly pursuing a greater appropriation of the information by the girls, both in expressive, symbolic and instrumental terms.

The conditions in which the intervention was carried out in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in certain restrictions regarding interaction with the Roma girls, which undoubtedly constitutes one of the main limitations of the project and the resulting analysis. The second limitation is based on the fact that the EE action addressed in this article ended up being forged from the agreement of the stakeholders involved in RoMoMatteR Alicante. This led to a significantly different EE format regarding the evaluation designs considered for the whole project, which intend to replicate the intervention sessions in four different locations and four different countries. This has had an influence on the ability to compare the results from Alicante with other locations where interventions took place. A third limitation is the lack of contact with the girls once the project ended. This has prevented a long-term follow-up of the empowerment process. In this same sense, the project has not registered information on the determinants of the process at the meso and micro levels. Many of these determinants can reinforce or reproduce power differences related to ethnic and gender discrimination, and should be kept in mind.

CONCLUSIONS

The intervention assessment by the participants, especially in a context of discrimination and poverty, reveal the potential of EE to reformulate from the objectives of the intervention process itself to the way activities are organized (characteristics and timeframe), as well as formulating the needs to be addressed. EE contributes to increasing the level of ownership by the people involved, and as consequence, they feel empowered. The need to improve and transform processes related to reproductive justice for women and girls, which has been the matter addressed by RoMoMatteR, is the main focus of this research. Yet, this transformation process does not arise spontaneously in the community. Interest is sometimes shown with an external factor that leads to change or a project, so that those needs that are felt, but not expressed, are channelled through an intervention design. This design can account for the level of appropriation and control acquired by participants to increase their control over their decisions (related to reproduction in this case).

The case study highlights that an increase in accessing socio-cultural and relational resources available reaches special relevance when deployed from a participatory approach. Thus, empowerment evaluation makes sense in a group setting. The participants develop levels of critical awareness in relation to the topics discussed through collective reflexivity and interactions. Empowerment is also an individual process, a process mediated through a group, under circumstances that favour critical thinking and collective deliberation.

Although the raison d'être of this text is mainly based on its contribution as a methodological proposal, some specific results of the output of the evaluation sessions within the framework of the project show additional implications when evaluating the tools used, therefore, confirming or qualifying certain aspects. Appropriation should not be only limited to internalizing or integrating process of the project results. It is completely the opposite, in fact. Appropriation within a participatory logic emerges in the design phases of the project when defining the goals, when configuring the intervention methodologies and the information registering tools and even, as observed in this case, the timing and changing the hierarchies between academic and research entities, the participants (the girls) and the community entities. Therefore, we could say that empowerment is not only the result wished to be reached at the end of the project, but an exercise of control and power that can be applied in the project itself. In this sense, the door is permanently open to debate that EE can be used in a project depending on whether there is interest or not in subordinating the technological/methodological dimension of a project in order to respond to the needs identified by the participating population itself.

In any case, the commitment to EE approaches does not pose a threat at all to other traditional forms of evaluation. Quite the opposite, as it offers the opportunity of methodological integration to enrich other benchmark evaluation options. However, in a process where the intention is to explicitly transform community reality, especially as in this case with girls belonging to ethnic minorities, their integration enables an essential approach if our intention is to assess the real influence of the projects.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This initiative is funded by the DG Justice of the European Commission in the Call for proposals for action grants under 2017 Rights Equality and Citizenship Work REC-AG #809813. Text editing work was supported by the Generalitat Valenciana Research and Development Programme (2022–2024) [ref. CIAICO/2021/019].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Not necessary.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

The project has received ethical approval from the University of Alicante.

NAME OF SPONSOR OF THE RESEARCH CONTAINED IN THE ARTICLE

The project mentioned in the text is funded by the DG Justice of the European Commission in the Call for proposals for action grants under 2017 Rights Equality and Citizenship Work REC-AG #809813.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Informed consent was obtained by all participants and their families in the case of minors.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIAL FROM OTHER SOURCES

Not necessary.

Biographies

Francisco Francés García-holds a PhD in Sociology (Special Award) from the University of Alicante, and he is currently a senior lecturer in the UA's Department of Sociology II, and a researcher at the Interuniversity Institute for Social Development and Peace. His main lines of research are social and citizen participation, participatory methodologies and social inequalities.

Daniel La Parra-Casado has been a senior lecturer at the Department of Sociology II, University of Alicante, since 2007. Director of the World Health Organization Centre on Social Inclusion and Health (Interuniversity Institute for Social Development and Peace, IUDESP, University of Alicante), 2012–2020. Member as an expert at the Spanish State Council of Roma People. Ministry of Health, since 2010–2016.

María José Sanchís-Ramón Predoctoral researcher in the Department of Sociology II of the University of Alicante. FPU program of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities. The main lines of research in which her activity is developed are ethnic minorities, social exclusion, gender and social participation.

María Félix Rodríguez Camacho Predoctoral researcher Department of Community Nursing, Preventive Medicine and Public Health and History of Science, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain. Technical staff at Federation of Roma Associations (FAGA), Alicante, Spain.

Diana Gil González is Senior Lecturer of Preventive Medicine and Public Health in the Department of Community Nursing, Preventive Medicine and Public Health and History of Science in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Alicante. Her areas of specialization as a teacher and researcher are social inequalities and their impact on health, the study of social discrimination, especially gender, ethnic and migratory discrimination.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.