Exploring possibilities for child participation in guideline development: The need for a fundamental reconsideration and reconfiguration of the system

Abstract

While the right of children to be involved in decisions that concern them has been widely recognised, they are currently barely involved in guideline development in healthcare. This paper aims to explore what a future guideline development system in which children are meaningfully involved might look like and to reflect on the transition required to achieve this. We used a systems innovation perspective, exploring child participation within its systemic context and complexity. To this end, we conducted 24 interviews with various actors, about their ideas on and experiences with child participation in guideline development in the Dutch system (between August 2018 and September 2020), complemented with a scoping review. The current system is characterised by a high-speed, rigid process that relies heavily on scientific evidence. Children are usually not included or taken seriously. The contours of a system in which children are meaningfully involved would differ markedly: children would be considered capable and taken seriously, and the guideline development process would be flexible, with time for interaction with children and discussion about the implications of their perspectives. We encountered few examples of child participation in guideline development worldwide, and believe our results are indicative of the situation in other Western countries. We propose the following actions: (1) Development of a discussion arena to create a joint vision on the aim of guideline development and subsequently the role of child participation therein. (2) Set up of transition experiments unbound by the current constellation, conducted by front-runners who are open to children's perspectives. These are essential to clarify pathways towards a future in which the voices of children are meaningfully integrated. It remains to be seen, however, whether there are sufficient actors who feel the necessary urgency for change.

INTRODUCTION

Only three decades ago, the right of children to be involved in decisions that concern them was internationally recognised, signalled by the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (General United Nations Assembly, articles 12 & 13). The Convention states that all children have the right to participate in decisions concerning their lives in a way that fits their age and maturity. In this article, we use the term ‘children’ to describe people aged 0–18 (General United Nations Assembly, 1989, article 1). In healthcare, there is increasing attention for children's inclusion in decision-making on the individual level (Park & Cho, 2018). Fewer developments are seen on the collective level, where decisions are made that affect children as a group (Weil et al., 2015). According to Franklin and Sloper (2006), children's participation in decision-making entails that they have the information required to understand the decision at hand, the arguments that are being made and the available options. A child should also have the opportunity to express wishes and views, and these should have influence on the decisions being made. Sinclair (2004) emphasised that if these steps are to translate into truly meaningful inclusion, child participation should not happen haphazardly, but be embedded within society and its institutions.

Guidelines are important in healthcare decision-making. Yet, child participation in the development of guidelines that affect them has only recently gained attention, indicated by the few (very recent) examples we found in the Netherlands and the UK only (Federatie Medisch Specialisten, 2016; Johnston et al., 2022; NICE, 2021; Taylor et al., 2016; van Zoonen et al., 2019). It still appears most common to include caregivers (Manickam et al., 2021; NVK, 2013) and/or clients after they reach adulthood (e.g. Denger et al. (2019), Word Health Organisation (2020)), rather than children. Academic knowledge about how children might best be involved in guideline development processes is very limited, as we only found one scientific article exploring this topic (Schalkers et al., 2017).

Schalkers et al. (2017) found that guideline development is expected to be a challenging context for child participation. This is largely based on experiences with adult client participation in guideline development, which still faces difficulties, despite its increasing practice (Schalkers et al., 2017). Dealing with differences between the perspectives of clients and professionals and integrating experiential and scientific knowledge are prominent challenges (Rashid et al., 2017; van de Bovenkamp & Zuiderent-Jerak, 2015; Wieringa et al., 2018). Other sectors that have included children in collective decision-making, such as child protection services, have encountered child-specific challenges regarding children's privacy and protection, their ability to provide informed consent and their awareness of the goals and implications of their participation (Sarti et al., 2018). Additionally, decision-makers often have difficulty imagining children's abilities and the roles they can fulfil (Sarti et al., 2018; van Bijleveld, 2019).

The inclusion of adult clients (let alone children) in collective decision-making has been described as a complex process that requires not merely an ‘add-on’ but a system transformation (Schölvinck, 2018). This means that the realisation of guideline development that integrates children's perspectives will require changes to the practices of all actors involved and to the structural elements that shape them (van Raak, 2016).

In 2018, we were presented with a unique opportunity to investigate the possibilities of child participation in guidelines, including the perspectives of many different actors. The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) commissioned a project on child participation in guideline development for Dutch Youth Healthcare. Many different actors from the Dutch system were involved in this project. Using the project's interview data, this paper explores what a guideline development system in which children are meaningfully involved could look like, to inspire and foster systemic change (Willow, 2022). Moreover, we reflect on the transition towards such a system and provide recommendations for action for policymakers, guideline developers and other actors involved.

METHOD

In this qualitative exploratory study, we conducted interviews and a supporting quick scoping review. These activities were conducted as part of a broader research project that aimed to create a roadmap to support child participation in guideline development in the Netherlands.

Participants

We conducted interviews to gather ideas about and experiences with child participation in guideline development. We strived to include people with various different roles in guideline development: guideline developers, healthcare professionals (working group members), policymakers, client representatives and scientific experts. We aimed to find people with child participation experiences, but anticipated these might be limited. We therefore also included people who had experiences with child participation in other policy-making areas (e.g. child protective services). We recruited participants through our network, internet searches and chain-referral sampling.

- Three client representatives were affiliated with patient organisations; two were not.

- The guideline developers worked at guideline-developing organisations and focussed on varying development phases. One specifically arranged client participation, one also had experience as a client representative and one also conducted academic research on client participation.

- The policymakers were from organisations that commissioned and assessed guidelines.

- Three of the researchers studied child participation in policymaking in and outside healthcare. Five of the researchers (also) studied client participation in guideline development.

- The healthcare professionals were members of guideline development groups of two guidelines in youth healthcare. At the time, we (the authors) experimented with child participation in these guidelines, as part of the broader research project.

- ‘Other’ in Table 1 includes someone with experience consulting parents for guidelines, someone who consulted children for diverse organisations and an advisor of client representatives.

| Participant | Relevant experience in the field as | Experience with or expertise on | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Client representative | Guideline developer | Policymaker guideline development | Researcher adult client/child participation | Healthcare professional in guideline development group | Other | Adult client participation in guideline development | Child participation | |

| 1 | ||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||

| 10 | ||||||||

| 11 | ||||||||

| 12 | ||||||||

| 13 | ||||||||

| 14 | ||||||||

| 15 | ||||||||

| 16 | ||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||

| 18 | ||||||||

| 19 | ||||||||

| 20 | ||||||||

| 21 | ||||||||

| 22 | ||||||||

| 23 | ||||||||

| 24 | ||||||||

Participants had experiences with various guideline types and topics (e.g. general practice, youth healthcare, mental healthcare, elderly care, (paediatric) specialist medical- and pharmaceutical care).

Interview design

We aimed to gain insights into participants' experiences with child participation. If such experience was absent, we asked about their experiences with adult client participation in guideline development. To structure the conversations, participants were asked to draw a timeline of a process they had experienced in which adult clients, parents or children had participated. They were encouraged to elaborate and reflect on the participation: what had worked well, what had not and why? Thereafter, they were asked to consider what these lessons might disclose about how meaningful child participation would have to be shaped. During each interview, we asked interviewees to define ‘meaningful’ participation. All interviews were conducted in Dutch by SH with the assistance of two interns. They were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim.

Supporting scoping review

We aimed to support and validate the interview data and deepen our understanding of the current guideline development system, using literature. We therefore conducted a quick scoping review of grey and academic literature (published until June 2022) for (1) examples of child participation in guideline development and (2) guideline development protocols and guidance documents. For (1) we used Google, Google Scholar and PubMed, using terms such as ‘child participation’, ‘-involvement’, ‘-consultation’ and ‘-perspective’ and method-related terms like ‘focus group’ or ‘survey’. All document types were considered potentially relevant, if they indicated children being involved in guideline development. The first five pages with resulting blogs, news items, full-text academic articles and guideline text were scanned. With regards to (2): throughout previous experiences with client participation in guideline development (from JB and CP) and the interviews, we had learned about influential protocols and guidance. We collected and scanned various documents interviewees mentioned and/or we knew are influential.

Theoretical framework

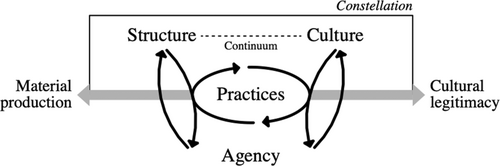

For this paper, we view guideline development not as a process but as a system with various elements, actors and dynamics (Grin et al., 2010). To better understand how children might be meaningfully involved in this system, we use the ‘constellation’ framework (van Raak, 2016). According to van Raak, a system (constellation) is made up of three main interacting elements: culture, structure and practices (CSP) (Figure 1). As child participation will require a systems change, this means it will require a change of the CSP of guideline development.

Culture refers to ‘the paradigms, norms, values and other immaterial elements or aspects structuring behaviour in practices of a system’ (van Raak, 2016, p. 91). Structure encompasses the ‘physical structures and resources, enforced regulations and legal rights, economic resources and other material elements or aspects structuring the behaviour in practices’ (van Raak, 2016, p. 91). Practices are ‘(typical) routines shaped by both agency, structure and culture of a system’ (van Raak, 2016, p. 91). Additionally, van Raak (2016) places agency in the model to acknowledge the role of humans: defining it as ‘the autonomous choices of individuals and possible collective agents in relation to the constellations’ (van Raak, 2016, p. 91). Van Raak (2016) also uses the concept of functioning, defined as ‘the way in which the constellation fulfils a (perceived) societal aim’ (p. 91). Van Raak (2016) explains that ‘the constellation does so through both material production of goods and services, but also by cultural production of meaning and legitimacy’ (p. 92). Materials in this context could be guidelines, and cultural legitimacy the way they are valued and applied.

From the perspective of the constellation framework, a system in which children are meaningfully involved means that its CSP are optimally adapted to their involvement. In other words: child participation is embedded in the constellation. Such a constellation (CSPem) may look very different from the current constellation (CSPc).

Analysis

We aimed to construct the current guideline development constellation (CSPc) and a vision of a CSPem, using our data. Doing so enables critical reflection on what is needed to achieve a transition. Such an approach is known as back-casting; it acknowledges that a systems transition cannot be forced by applying a predetermined set of solutions, but depends on the state of the current system and its envisioned future (Robinson, 1982).

CSP construction

To construct CSPc, SH (using Atlas.ti 9) coded transcripts for characteristics of the currently dominant CSP. Sometimes a ‘characteristic’ was mentioned as such by participants (e.g. when explaining how processes work), others were a result of our interpretation of their expressed ideas (e.g. the attitudes they expressed towards child participation). Subsequently, a description of CSPc was drafted; supported and validated using the identified protocols and guidance documents.

To construct CSPem, transcripts were coded for essential elements of or preconditions for meaningful child participation in guideline development respondents mentioned. These were categorised into CSP. When participants had discussed experiences with adult client participation we deemed relevant, we interpreted their possible implications for CSPem. Subsequently, a description of CSPem was drafted. All codes and constellation descriptions were regularly discussed with the other authors and subsequently refined.

Reflection on the transition

We then wanted to reflect on the transition towards CSPem. We first identified the main discrepancies between CSPc and CSPem. Systems innovation literature described various important elements to overcoming these discrepancies. These include a joint vision, a sense of urgency, experimentation with new practices and adequate competences of actors (Broerse & Grin, 2017; Grin et al., 2010; Loorbach, 2010). We analysed on our data to reflect on the degree to which these elements are currently present.

Ethical considerations

Permission from a Dutch ethics committee was not needed for this research. We adhered to the national Code of Ethics for Research in the Social and Behavioural Sciences involving Human Participants (VCWE, 2018). All participants gave consent to use their anonymised data.

RESULTS

First, we describe the current constellation (CSPc) of guideline development in relation to child participation. Next, we draw the outlines of a constellation in which children are meaningfully involved (CPSem). We then reflect on the elements that are important for a transition of the current constellation to CSPem. As (perceptions of) the constellation's aim and functioning are highly intertwined with its structure, practice and mostly culture, we address this concept under ‘culture’ and in the reflection.

CSPc: The status quo of (child participation in) guideline development

The current constellation of guideline development is highly structured and practices rarely include any child participation activities. The dominant perception is that the aim of guidelines is to address the issues faced by healthcare professionals, and that they should be constructed using scientific evidence. The current culture is characterised by beliefs that children have limited capacities and can be represented by adults.

Structure and practice

In the Netherlands, various organisations initiate or commission the development or revision of a guideline. They may ask another organisation to guide the development process for them. Guideline development commonly follows a standardised multi-phased process, comparable with other countries (Rosenfeld et al., 2013) that is highly structured by protocols, methods and tools (Brouwers et al., 2016; Regieraad Kwaliteit van Zorg, 2012; Steinberg et al., 2011). The process starts with a ‘bottleneck analysis’, exploring the issues that healthcare professionals face around a certain subject (Hilbink et al., 2013). Issues are translated into questions framed according to the PICO format (the Population, the Intervention, the Comparator, and the Outcome) (Zhang et al., 2019). A guideline development group is formed, consisting primarily of healthcare professionals. Guidelines concerning children may also include one or two adult representatives of children's perspectives (e.g. from a patient organisation). No child participation occurs. To answer the PICO questions, a scientific literature search is conducted. The collected evidence is evaluated using methods like GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation), and presented and discussed during guideline development group meetings (Siemieniuk & Guyatt, 2019). The group then formulates the recommendations. A draft guideline is usually open for review, either publicly and/or upon invitation, before it is approved by all contributing stakeholders and implemented. Sometimes a client version of the guideline is made.

Child participation has low priority and is competing with other activities for funding and time. Various participants pointed out that child participation is usually not a prerequisite of commissioners and that no funding is allocated to facilitate child participation.We have experienced so far that the trajectory is such an express train that organising additional activities is very difficult. [Participant 24]

Culture

In the currently dominant constellation, the perceived aim of guideline development makes child participation unnecessary or even undesirable. Moreover, various beliefs concerning children discourage child participation.

Aim of the constellation

I observed that guidelines were not about content but more about interests. You can see that when there is no patient representative present… [laughs] That it became a kind of interest game. [Participant 6]

Everyone wants to assert themselves. I think you notice that in such a [guideline development] group. [Participant 20]

Knowledge needed and role of client participation in its functioning

In the current constellation, it appears that the added value of participation of adult or underage clients is mainly seen when scientific evidence is inconclusive. However, it is often considered non-essential information and is put in a paragraph with ‘additional considerations’. Many participants said that children's perspectives might provide context for the real-world implications of recommendations, but in the current constellation this is a nice to have and certainly not a need to have.It is intended as ‘which bottlenecks there are from the care provider’, those in particular, right? And we must then answer those questions. So that they do not have to dig through literature every day to know the latest state of the science. [Participant 6]

Beliefs concerning children

Most participants with experience in guideline development also believed that adults are (at least to some extent) capable of representing children's views. While all participants acknowledged that children's views and experiences might not match their parents', ‘parent participation’ in the current constellation is seen as a synonym for ‘child participation’ and it is accepted that adult representatives from patient organisations represent children during guideline development. Participants with more extensive experience in child participation said that these beliefs can be attributed to wider societal beliefs concerning children.I personally also find that a difficult question; at what age does participation mean you can really have a voice in the conversation. Because it is nice to question a 16-year-old, but I do not think much will come of this. [Participant 23]

CSPem: Vision of a constellation that meaningfully involves children

During the interviews, it appeared difficult for most people to envision what meaningful participation of children in guideline development may look like ideally. Participants with expertise in child participation could not clearly describe ‘how’ it should be done, but did mention conditions and essential elements. Based on the collective wisdom of our participants, we can construct the contours of a future CSP in which children are meaningfully involved.

Practice

According to these participants, interactions that lead to insights into children's perspectives often require translation of the ‘adult’ situation or problem to a version a child can comprehend and may include elements of play and games or storytelling:You have to consider very carefully, what do these children need to reach their full potential? That is different for younger children, it is different for less-educated children; it is different when you have cystic fibrosis than when you have something else. [Participant 15]

Furthermore, in this practice, participation entails multiple interactions rather than a one-off consultation activity (e.g. a questionnaire). Child participation experts said this is essential to gain meaningful insights into children's perspectives:There is an adult question and we translate that question to the children's world. We do that through a fairy tale with [fictional creatures] and no people. We do that because an IT problem is of course not exciting at all. Sometimes we also talk about child poverty or child abuse, or poverty in general. And then you take it out of the children's world [using these fictional creatures]. [Participant 14]

These various interactions commonly involve combining multiple methods (e.g. introductory interviews followed by creative group activities). This has several effects. It helps to build a trusting relationship between children and facilitators. Additionally, it allows facilitators to learn more about the children's capacities, such as how they (non-verbally) express themselves, thereby improving subsequent interactions. Various child participation experts deemed this essential for adults to gain a deeper understanding of children's experiences and views:It is also very important that you build a relationship with them, and that they want to share things with you. [Participant 6]

So participation requires time for quality and depth, and is also an iterative process. So that it is not a one-off consultation, but that you really have to start working together. [Participant 15]

Structure

While they found it hard to describe an alternative development process and new structure, they mentioned the following preconditions:Then the process simply has to be set up in such a way that there is room for it. […] that is how it should be: if you want clients and family to make a worthy contribution, you have to make room for that too. [Participant 24]

-

Early on in the process, the involvement of both children and client representatives is planned, and they are included in the bottleneck analysis. Explicit thought is given to when in the timeline significant decisions are made and consequently when children's perspectives should be brought into this process so they can have an impact:

Of course, you can always make a kind of paragraph with what the client perspective is, but that has no impact. You have to think very carefully about which moments in the process you involve people, so that they can also have influence: so their input cannot be immediately dismissed. [Participant 9]

- The process is flexible; experts on child participation said that child participation is not always a straightforward process and flexibility is key. Flexibility means that the process can be delayed or altered when necessary, for example when the input from children means that more guideline development group meetings are needed or that additional people should be involved.

- There are additional participation initiatives that pre-date or transcend (multiple) guidelines so that insights that may have an impact on various guidelines can be gathered, since children's real-life experiences and issues are rarely confined to one guideline topic.

- There is sufficient time for reflection and discussion in the guideline development group about the implications of children's perspectives. This also means having sufficient meetings.

- There is sufficient funding for the execution of participation activities.

Culture

In CSPem, the perceived aim of guideline development makes the inclusion of children necessary for its functioning. This also gives rise to a culture in which children and their perspectives are taken seriously.

Aim of the constellation

Ultimately, it is about the care for the patient, who is the main character in this story. So how is it possible that […] the wishes and needs and bottlenecks experienced by that patient group are not central to that process. That is of course too bizarre for words. [Participant 2]

Knowledge needed

If you started more from the demand from and the issues in care delivery, I think you would need a much more inclusive definition of knowledge to come up with good recommendations. [Participant 11]

Beliefs concerning children

Taking children seriously also means that involved adults are able open up their own ideas and beliefs. In CSPem, adults are genuinely interested in and open to the views that children express, and not only focused on getting answers to their own questions.At any level, you can ask what the child thinks. At every level. […] It starts the moment a baby is born. [Participant 19]

If you really think beforehand 'we know better'; then do not do it. [Participant 9]

Reflection on the transition to CSPem

The current constellation differs markedly from CSPem. In this section, we reflect on the transition process towards CSPem. We do so by discussing four important elements of systems transition: (1) the development of a widely shared vision of CSPem, (2) bridging of discrepancies between CSPc and CSPem, (3) experimentation and (4) a sense of urgency. We relate these to the experiences and opinions of our participants.

Developing a joint vision

An important element in any transition is the existence of a joint vision of the future, shared by all actors involved (Loorbach, 2010). Although we (the authors) constructed a vision of CSPem based on inputs from different participants, this vision is not shared by all participants. We observed that participants perceived the guideline development constellation's aim and functioning differently. First, participants appointed different end-users to guidelines. Second, some broadly stated the aim was to ‘improve care’ while others said it was to draft recommendations for practice. However, in practice, there appears to be a tendency to treat the summarisation of scientific evidence as the aim. Depending on the perceived aim, participants found that child participation was required for the functioning of guidelines, or they deemed it unnecessary or even a threat its functioning. Some felt guidelines should start with clients issues (and thus children's), others emphasised the professionals' issues were central to the process. They consequently also disagreed on the knowledge types that should be used to draft recommendations—scientific evidence, professionals' expertise or perspectives of (underage) clients. A few participants doubted whether certain issues in healthcare now addressed by guidelines (e.g. communication) should be addressed otherwise (e.g. with educational modules). Before a vision on child participation can be developed, actors should first develop a joint vision on the aim of guideline development. Currently, no ‘arena’ seems to exist in which this is broadly discussed.

Overcoming discrepancies between CSPc and CSPem

Here we reflect on changes are needed to overcome the discrepancies between CSPc and CSPem. First, to achieve the practices of CSPem, actors will require new competences. Moreover, achieving the structural preconditions described in CSPem will require an overhaul of the current development process.

The competences needed to practice child participation

The practices described in CSPem will likely require competences (knowledge, attitudes and skills) that many stakeholders, especially guideline developers and health professionals, currently lack.

Knowledge: Our interview data indicate there is a lack of knowledge on how child participation can be shaped and executed meaningfully. Many interviewees, especially guideline developers and healthcare professionals, were uncertain of what child participation might look and what questions they should ask. A few guideline developers had involved children in the past. However, they said children had given no input, or input they did not know how to use, for example, because they deemed it to be outside the guidelines' scope. Child participation experts suggested the lack of input might be caused by unsuitable questions and inappropriate methods. This already happens with adult client participation: a policymaker described a past experience, where guideline developers had sent parents a complete guideline draft, instead of adapting the participation approach to their abilities and needs. As a result, parents could hardly provide input.

However, two researchers studying child participation found this less problematic and urged that people can acquire these skills through practice.Organising a focus group is not something you just do. […] We hire an independent moderator, [there is] reporting. And that also comes at a cost. […] You do not simply do it on the side if you want a good focus group. Often that is not seen: 'oh, but you can do that, right?' [Participant 6]

- Explicitly discussing whose knowledge is important for developing recommendations, right at the beginning of the development process. This way the value of children's perspectives can be established early on.

- Hearing children's perspectives directly (e.g. children presenting results from a focus group).

- Reflecting sufficiently in the guideline development group on the input gathered from child participation practices: currently, this does not always happen.

Structural discrepancies

Various participants mentioned that the dominant structures and processes appeared to have become ‘simply the way it is done’. Van Raak has noted that in transitions, ‘the ‘grey area’ between structure and culture would be of special interest, as reframing of what is absolute and what is relative could be part of the ‘opening up’ of a constellation or system’ (van Raak, 2016, p. 88). In other words, a transition to CSPem requires actors to reconsider the widespread notion that the current structures of guideline development are set in stone – making a cultural shift also highly important.The problem very much lies within seeing the decision-making process as a given: ‘Well, this is just how it goes, so this is what [participation] has to fit into. Whilst you could also say that the decision-making process has to be broken open if you want to give that perspective a real place. [Participant 12]

Experimentation

- What should the goals of child participation be; how should consultation activities be shaped to achieve these goals? Child participation experts advocated for an ‘open approach’, while often also recommending clear, context- and case-dependent goals. As participants could hardly provide concrete examples, this likely a difficult step, especially in early experimentations.

- Who should lead the participation? Some participants would prefer an external expert to do this, others proposed patient organisations or guideline developing organisations could.

- Which children should participate, how can they be found and what questions should they be asked? The broader the scope of a guideline, the harder it appeared to be for policymakers, guideline developers and patient organisations to determine which children should participate and think of appropriate and clear questions. For example, paediatric treatment guidelines for specific diseases have a distinct target group, while youth healthcare guidelines target all children between 0 and 18.

- Child participation experts deemed direct participation of children in the working group undesirable. Simultaneously, client's perspectives have limited power in the politics of the guideline development process, likely even more so when clients are children, given the various cultural factors described earlier. This raises the question who should be the safeguarder of children's perspectives in the guideline development process. When asked, interviewees suggested this could be a client representative, group chair or an external party.

Furthermore, there seemed to be very little exchange of experiences and lessons learned among the limited initiatives. This lack of experimentation space indicates that a transition to CSPem has a long way to go.I think in general we very quickly decide to just ask parents. Because that is kind of comfortable I guess. […] 'I am going to ask people about a subject they probably know little about', that is the thought. Then it is comfortable to have an adult at the table – probably you will know how to deal with that. I think that is a shame. [Participant 7]

Sense of urgency

Furthermore, various participants suggested that clients in general and children specifically might not always have an opinion on, interest in or experience with certain subjects. The widespread belief that parents, adult client representatives or healthcare professionals can represent children may further reduce motivation to involve children directly. Overall, despite participants expressing that child participation is important, the elements above result in a low sense of urgency for change. Moreover, they indicate that a transition to CSPem has not taken off in the Netherlands yet.Within the guideline development process, you always try to find everything in literature. And if there is no literature on it, you go to alternative sources. But I do not think it is appropriate to bring up things at that time. […] You are doing new research, and a guideline is not new research, but putting together all the research there is. [Participant 4]

DISCUSSION

In 2004, Ruth Sinclair concluded that child participation should become ‘firmly embedded within organisational cultures and structures for decision-making’, making it ‘an integral part of the way adults and organisations relate to children’ (Sinclair, 2004, p. 116). In this study, we have constructed a vision of what the guideline development processes would ideally look like if child participation is an integral part of structure, culture and practice. However, our data reveal that two decades after Sinclair's call to action, a transition to this future is barely under way and many barriers still exist. Dominant beliefs about the aims of guideline development and the knowledge needed to create them shape protocolised and high-speed guideline development processes. These leave little room for the meaningful inclusion of children, which requires space, time, flexibility and active effort to gain insights into the lived experiences and perspectives of children. There is currently limited experimentation and a minimal sense of urgency for change. Most actors involved use their agency to perpetuate the current system's CSP, rather than to stimulate change.

Barriers to transition

We have identified various barriers to the realisation of a transition to CSPe. Two underlying cultural factors seem crucial: the central role and interpretation of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and the image of children.

The gold standard of guideline development is based on the concept of EBM, which is often cited to be a ‘systematic approach to clinical problem solving by the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values’ (Akobeng, 2005, p. 1). As the flow of research data increased, EBM pioneers devised clinical guidelines to inform clinicians about state-of-the-art research evidence (Sackett et al., 1996). The ‘purist’ view that recommendations for guidelines should be based on scientific evidence alone has been widely challenged since that time (Wieringa et al., 2018; Zuiderent-Jerak et al., 2012). However, formulated recommendations are not the results of scientific evidence alone but incorporate implicit knowledge gained through politics and complex reasoning processes (Nairn & Timmons, 2010; Wieringa et al., 2021). Despite these calls for change, the purist view is still dominant and problematises the incorporation of clients' knowledge in many countries—even in the UK, where front-runner NICE has involved clients in guideline development for years (e.g. Armstrong and Bloom (2017), van de Bovenkamp and Zuiderent-Jerak (2015), Wieringa et al. (2021)).

Our study indicates that the tendency to neglect clients' experiential knowledge is even stronger when clients are children. This is caused foremost by a widespread cultural tendency to view children as ‘incomplete adults’ who are unable to fully express themselves, are in need of protection and can be better represented by adults (Norozi & Moen, 2016). This jeopardises the upholding of children's perspectives during the political negotiation processes of guideline development. It has been shown that this image of children impacts policymakers throughout the (Western) world (Holzscheiter, 2021; Janta et al., 2021; Perry-Hazan, 2016). This often results in children's voices having a negligible impact on policies (Janta et al., 2021; Perry-Hazan, 2016). Much has been written about balancing children's rights to protection and participation, and, for example, avoiding overburdening them (Holzscheiter, 2021). Where this balance should lie has been often debated in literature (e.g. Lundy (2018), Moyo (2014)). While for guideline development, this should be researched more in-depth, we believe it should be weighed carefully within each context and with each child.

Structural and practical barriers also need to be overcome. The current rigidity and speed that characterise Western guideline development processes (Rosenfeld et al., 2013) hinder meaningful inclusion of children and require an overhaul. More flexibility, time and resources are required to gain insights into the perspectives of children and to integrate these throughout the development process. The extent of the overhaul required and the resulting guideline development process are still unclear, though. Furthermore, there are still insufficient competencies for and knowledge about the execution of child participation in guideline development.

This all sketches a rather gloomy picture. However, there are some interesting niche developments. There is an increasing interest in experimenting with the inclusion of children's perspectives in guideline development. ZonMw commissioned our study in the Netherlands and as discussed in our introduction, we found some recent examples in grey literature. In the UK, a recent NICE guideline detailing good patient experience for babies, children and young people, included them in its development (NICE, 2021). Despite these promising first steps, we think it will require time for the dominant culture to shift and children are taken seriously guideline development processes. Next we provide some directions on how such a transition pathway could be shaped.

Stimulating a transition

We believe that all actors involved should carefully consider how child participation fits with the aim of the guideline development constellation and its functioning (van Raak, 2016). For such a discussion to be fruitful, it is necessary to iteratively develop (1) a platform in which actors jointly co-create a shared future vision and an agenda, including a list of unanswered questions, and (2) a safe space for experimentation in which to explore different ways to achieve meaningful child participation in guideline development and the appropriate structural elements to support this, and to shed light on the added value that child participation can have.

In relation to (1), our data show that currently there is no platform or dialogue space in which to discuss the future of child participation and guideline development. In transition management, the development of a ‘transition arena’ is key to building a vibrant community of practice that will develop a shared vision and transition agenda (Loorbach, 2010). Members of such an arena concerning child participation should be individuals from various organisations in the system that are open to children's perspectives and new ways of working. The development of a shared vision requires debates on various cultural aspects of a system, that is, the aim of guidelines, the knowledge needed to achieve this aim and the value of children's perspectives and their participation.

Regarding (2), more experimentation is needed to gain deeper insights into the added value that child participation can have in different types of guideline development, how it can be shaped, what new structures are required and should pay attention to the balance between rights to protection and participation. This requires an open space in which various front-running actors collaboratively explore new ways of working, unbound by the rules and restrictions of the current constellation. Their focus should be on long-term goals instead of short-term solutions led by, for example, deadlines (Loorbach, 2010; van den Bosch & Rotmans, 2008). It is essential that these experiments are not bound by the established guideline development process but can instead explore new forms. Experiments could start with a type of guideline in which child participation is more self-evident, for example, guideline with a clear, relatively narrow target population and clear practical implications.

Strengths and limitations

As the participants of this study had limited experience with child participation, synthesising of a future constellation required considerable interpretation of data. However, this interpretation allowed us to move beyond the current unknowns and uncertainties and provided prospects for action. We have sketched the contours of one constellation, but there might be other potential constellations. Our outline does not challenge the notion of a guideline with care recommendations as the desired product for improving care nor as the desired arena for child participation. As there is uncertainty about the exact goals and scope of guidelines, this could be an opportunity to consider other modes of inclusion to improve care within a less restricting frame. Moreover, this study aimed to draw a CSPc and CSPem of guideline development in general—future research should investigate the suitability and specifics of child participation in different types of guidelines.

In our study, we found limited examples of child participation in guideline development in the (grey) literature, and this studies' more internationally oriented participants cited little examples. If more examples do exist, there is clearly little knowledge sharing and the few examples we did find in the Netherlands and the UK were not systematically analysed.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that currently little is known about how children might be meaningfully involved in guideline development. However, our results indicate that from a constellation perspective, a guideline development system that meaningfully involves children looks vastly different from the currently dominant CSP. These results probably indicate the situation in other Western countries too. It is essential to set up a transition arena to develop a joint vision of the rationales of (child participation in) guideline development and to have innovative experimentation spaces to clarify the possible pathways towards a future in which the voices of children are meaningfully integrated.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Simone Harmsen: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Conceptualisation. Jacqueline Broerse: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Reviewing & Editing. Carina Pittens: Supervision, Project Administration, Formal Analysis, Conceptualisation, Writing—Reviewing & Editing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the project group for their partnership and reflections during the wider research project, which have aided our understanding and interpretation of the data. We also thank Lotte Stribos and Lisette Faber for assisting Simone Harmsen during the data collection. The authors would like to thank the participants for sharing their experiences and thoughts.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), under funding no. 732000205, as part of the programme ‘Richtlijnen Jeugdgezondheidszorg 2013-2018’ (no. 732000000).

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

Upon screening by the ethics committee of the Vrije Universiteit Faculty of Science, they decided that further ethics approval was not required for this research.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

All participants gave consent to use their anonymised data.

PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE MATERIALS FROM OTHER SOURCES

Not applicable.

Biographies

Simone Harmsen is a researcher with an interest in researching the dynamics and stimulating the dialogue between science and society. Her PhD dissertation focuses on how the voices of clients and other societal actors can be better integrated into the complex health (research) system.

Jacqueline E. W. Broerse is professor of innovation and communication in the health and life sciences (with focus on diversity and social inclusion) and Director of the Athena Institute, Faculty of Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Carina A. C. M. Pittens is assistant professor of patient and public involvement at the Athena Institute, Faculty of Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. She has been involved in numerous (inter)national research projects where she has facilitated the creation of meaningful patient involvement in various domains and studied the effect thereof.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to the nature of this research, the participants in this study did not give consent for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.