How Badly Does India Need Biologics for Severe Asthma?

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

The treatment modalities for severe asthma have substantially changed in the past decades with the discovery of molecule-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), commonly known as biologics. Unlike corticosteroids (CS) that create a blanket anti-inflammatory effect, these agents work on specific inflammatory pathways by targeting immunoglobulin E (IgE), interleukin (IL)-5, IL-4, IL-13, and a more recently discovered thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) pathway. While these personalised treatment options have transformed care for many selected patient populations in high-income countries, their applicability to the low-middle-income countries like India requires more discussions on clinical relevance. In a country like India, where basic asthma management is often inadequate, the rush toward biologics may represent a misplaced priority and thus warrants a more careful approach. This consideration is especially crucial when examining asthma management practices within India.

In India, where asthma affects over 35 million people, the case for biologics is tenuous, not due to a lack of clinical efficacy but due to fundamental gaps in the infrastructure of asthma diagnosis and care, poor adherence to standard therapies, widespread underdiagnosed comorbidities such as allergic rhinitis (AR), and a milieu of several environmental factors, including extremely high air pollution. In this commentary, we argue that biologics in asthma care in India have still miles to go, as a significant proportion of difficult-to-control asthma cases are mislabelled as ‘severe’ asthma cases and without resolving this core issue, biologics offer limited value in reducing the burden of asthma in India. There is no doubt that biologics are extremely useful for a small subset of patients with eosinophilic or allergic asthma, but in countries like India, where simple spirometry is not accessible in most parts of the country, let alone access to any specialised allergy testing or blood biomarkers, finding the right patient group for biologic therapies is seemingly unrealistic.

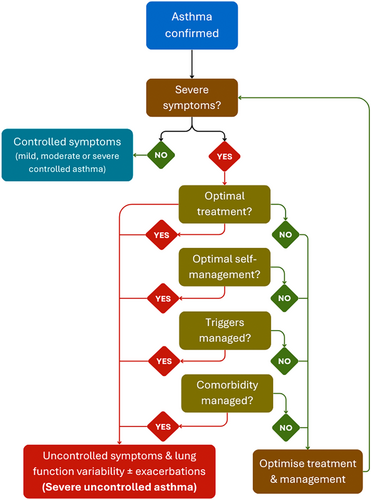

Let us focus on the primary question: how should we define severe asthma? Globally, severe asthma is defined as asthma that remains difficult to control despite optimal treatment with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and additional controller therapy, and optimal self-management in addition to the management of triggers and any comorbid conditions (Figure 1). However, this algorithm is rarely followed in India, and many patients with just difficult to control asthma are mislabelled as severe asthma without any guideline-based diagnostic approach in the first place. This overestimates the actual severe asthma cases where the disease is ‘truly’ severe despite full compliance with the treatment and management modalities.

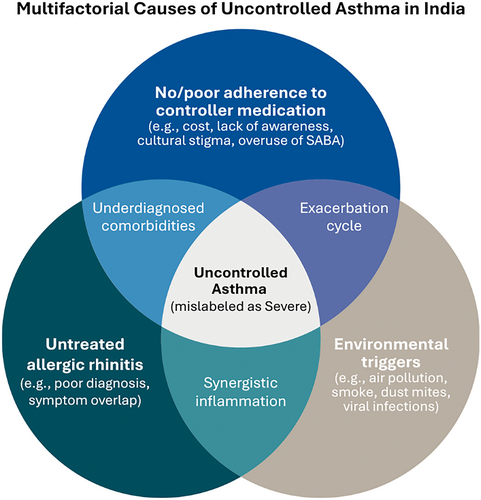

The heuristic scenario of difficult-to-control asthma is primarily dependent on three fundamental pillars: adherence, comorbidities of AR and environmental triggers (Figure 2), of which poor adherence to controller medications remains the major determinant. The Asthma Insights and Management in the Asia Pacific (AP-AIM) study revealed that roughly 18% of Indian asthma patients used ICS, with most relying on oral bronchodilators or steroids for symptom relief [1]. This scenario is opposite to the 2023 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, which recommend a low-dose ICS like budesonide and long-acting β2-adrenergic agonists (LABA) [2]. ICS is severely under-prescribed in India [3], where short-acting β2-adrenergic agonists (SABA) remain the most commonly prescribed and over-the-counter (OTC) purchased asthmatic drugs [4]. This poor compliance is the result of misconceptions about steroid safety, preferences for oral medications over inhalers, and economic conditions often leading to treatment discontinuation. India spends approximately USD 9.41 billion annually on asthma treatment, and most of it is out-of-pocket expenditure, as almost no public or private health insurance schemes currently cover routine prescription medicines [5, 6]. This financial burden is also one of the major reasons for the lack of compliance with long-term treatment. In a country where a ₹500 (USD 6) per month controller medication is an implausible burden to many families, spending ₹25,000–60,000 per month (USD 300–700) on biologics is a luxury even to those patients who are financially well-off. Moreover, we lack credible data on patient compliance rates or dropout rates from asthma biologics after 1, 2 or 5 years of treatment.

It is important to consider that AR is one of the major comorbidities in nearly 70% of asthma patients and despite this comorbid burden; however, this remains a fundamental oversight problem in asthma management in India. In the light of the ‘unified airway disease’ concept, where upper airway inflammation aggravates lower respiratory tract pathology [7, 8], AR not only results in persistent inflammation in the lower respiratory tract, but also AR-induced nasal blockage may force patients to breathe through the mouth, exposing the lungs directly to unfiltered airborne contaminants. In cases where AR is untreated or minimally controlled, using biologics for asthma may provide limited benefits if the nasal condition remains persistent. While several randomised controlled trials have demonstrated that AR management by intranasal corticosteroids significantly improves both upper and lower respiratory outcomes [9], in reality, AR remains mostly undertreated in India. Moreover, biomarker-based phenotyping of difficult-to-control asthma, which is a prerequisite for selecting appropriate biologic therapy, is rarely done in India due to limited resources. Thus, in the absence of a precise diagnosis, prescribing biologics is both logistically difficult and scientifically imprecise.

Apart from the comorbid condition, environmental triggers such as exposure to air pollution, second-hand smoke, pollens and viruses also contribute to asthma exacerbations, even though patients remain adherent to optimal treatment modalities. In cities like Delhi, where air quality plummets in winter seasons every year, hospitals experience a high number of admissions or emergency room visits due to aggravated asthma symptoms. Similarly, seasonal flu affects asthma patients significantly. Immunisation against seasonal flu can significantly reduce asthma exacerbations, hospitalisation or emergency department visits during the flu season [10]. However, unlike other developed countries where flu vaccines are available under the federal or provincial healthcare systems, such practice is non-existent in India. Moreover, the availability of the vaccines is also limited in private healthcare systems, and their costs are also out of reach for many individuals.

In our opinion, we need to strategise optimal asthma therapy in a systematic way, but first, we need to set the priority for improving basic asthma management. Physicians must be vigilant about the treatment adherence of their patients. This can be achieved by emphasising patient education programmes, breaking the myths about ICS safety, particularly among parents of young children. Patients should also be educated about the long-term risk of using only reliever medications such as SABA. Concurrently, pulmonologists must also ensure to integrate AR management into standard asthma care. Simultaneously, not only the diseases, but also the aetiology of those diseases must be taken into consideration, such as avoiding allergens and minimising exposure to air pollution, and getting vaccinated against influenza, particularly for high-risk asthma patients. Although most physicians follow guidelines-based therapy, keeping track of compliance or symptom control is rarely followed. Therefore, before considering biologics, physicians must also mandate a rigorous checking of compliance and symptom control over the past months through questionnaires or even by advising their patients to maintain a diary of their regular medication schedule and symptom control. It is also important to develop capacities for asthma phenotyping, which is a must before considering biologics.

A significant number of patients with severe symptoms arriving at the tertiary care facilities are from rural areas, and it is not just that their asthma control is poor, but because, in most cases, their asthma was not even diagnosed properly. Unlike diabetes or hypertension screening at the primary health centres (PHCs), we still do not have any infrastructure to detect chronic respiratory diseases. Also, there is limited availability of asthma medications, particularly inhalers, in pharmacies or PHCs in rural areas. We urgently need a substantial upgradation of primary care facilities, not just to increase the diagnostic infrastructure, but also to make the medications available to those patients. Biologics certainly have a role in selected groups of well-characterised, treatment-refractory asthma patients, but for the vast majority, we must fix the fundamental issue—the basic diagnosis and management.

Author Contributions

Su.M. conceptualised and wrote the manuscript. K.T.P. and S.M. revised and critically assessed the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated in this manuscript.